Gaza Lives: Notes from Film Works for Palestine

“Dehumanization is the prerequisite of most forms of violence,” writes the Palestinian-American poet and clinical psychologist Hala Alyan in an opinion piece for The Guardian. She states that even before the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) drop a bomb on displaced civilians living in tents, the act is institutionally rendered negotiable based on the disposability of Palestinian lives as a presumed fact. The repetitive image circulation of burnt, maimed and incapacitated bodies in the media duly contributes to the dehumanisation process as the viewing public gradually becomes “psychically numbed to them.” Consequently, Palestinians disappear into ‘alleged’ masses and a death toll so unimaginable that “it becomes impossible to imagine their nicknames or favourite songs.”

Alyan was writing this in the wake of the Rafah Tent Massacre last May, when the image of a decapitated child started circulating widely on social media. This week, as another image from the IDF’s bombing of the Al-Aqsa hospital shelter proliferates the internet, I am reminded of her claim that unremitting dehumanisation through discourse, policy or action does not only concern the dehumanised but also reversibly siphons the inhumanity of all those who perpetrate it by different means. It is, after all, our connivance in the ongoing genocide when we look past the individuality of Palestinians and bracket them as victimised masses. What might our attending to Palestinian lives look like, especially by their creativity, subjective voices and diverse forms of articulating resistance?

.png)

Poster of Film Works for Palestine.

Last month, I was fortunate enough to be a part of the organising team of “Filmworks for Palestine” a three-day event (5th–8th September) staged parallel to the Toronto International Film Festival (TIFF) at the Innis Town Hall of the University of Toronto. The programme sought to create an alternative space for filmmakers, industry workers and TIFF attendants, among others, who are committed to the global struggle for Palestinian liberation. On 5 September 2024, it opened with the fourth edition of the “Gaza Lives” event periodically presented by the Toronto Palestine Film Festival (TPFF), where a line-up of speakers and performers paid tribute to the art and artists of Gaza. As Dania Majid, the programmer at TPFF, said in the opening note to the event, the task is to carry forward the stories that Gaza’s visionary individuals embodied through their creative work across various mediums.

.jpg)

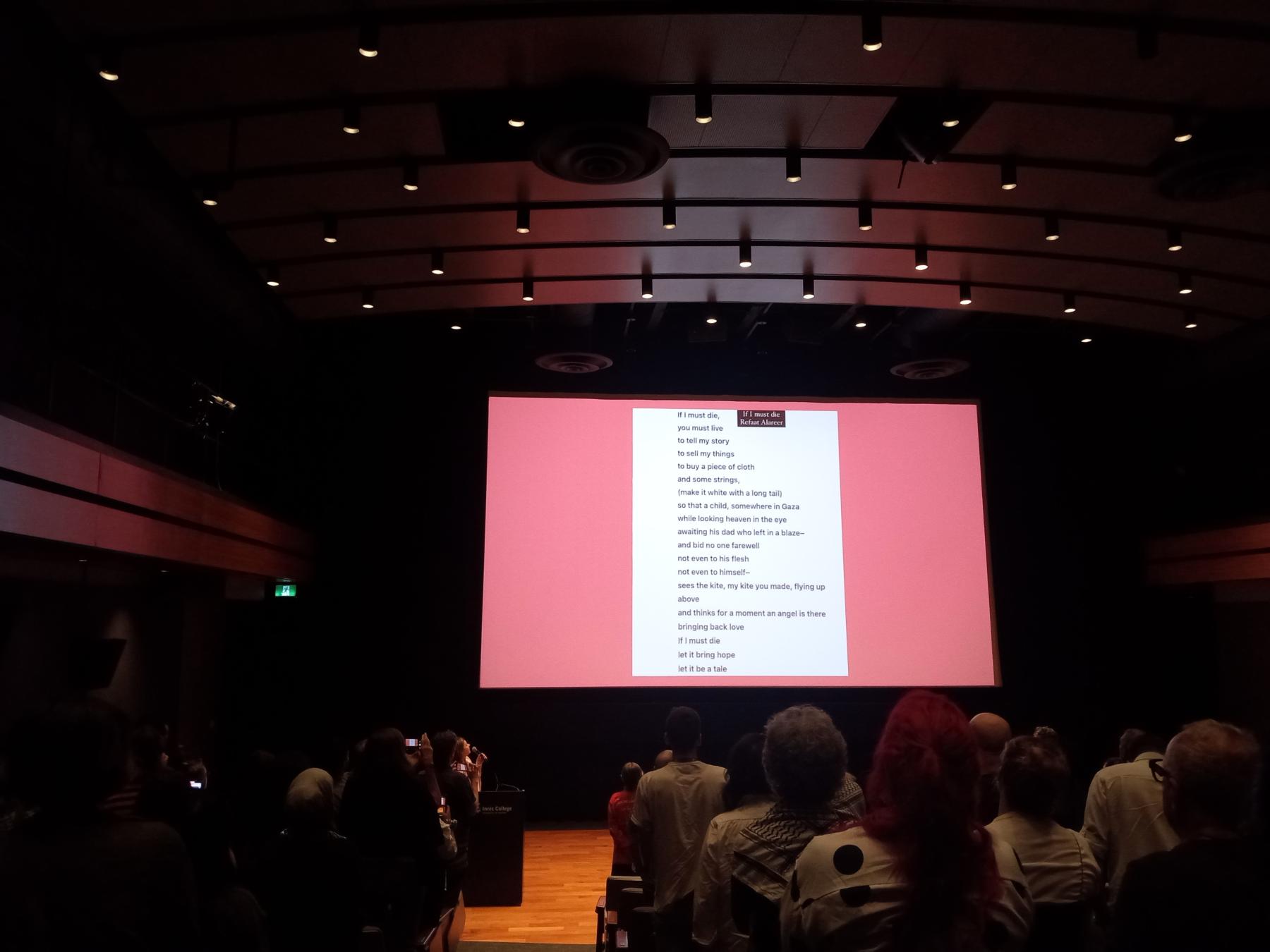

As the first day of "Films Works for Palestine" ended, the audience collectively read the poem “If I Must Die” by Refaat Alareer. Meanwhile, at TIFF, several demonstrators also intervened during the festival director’s opening speech on 5 September, demanding that the festival cut ties with one of its major sponsors, the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), for the institution’s extensive investments in war technologies advancing the genocide in Palestine.

Audience joins the reading of Refaat Alareer's "If I Must Die".

“Gaza Lives” is also about honouring solidarity and community building. In this version, TPFF brought together the life and work of ten Gazan artists, individually presented on stage with a compilation of their creative production. The artists honoured included the writer Refaat Alareer, musician Lubna Alyaan, painter Heba Zagout, live video blogger Medo Halimy, poet Huba Abu Nada, painter and educator Fathi Ghaben, writer and musician Yousef Dawas, painter Mohammed Sami Qariqa, poet Saleem Al Naffar and musician and poet Elham Farah. The ten invited presenters who introduced the works of these Gazan individuals included artists and writers like Robyn Maynard, Amar Wala, Serene Husni, Sofia Bohdanowicz and Roula Said. It also collected the names of fifty more artists and cultural workers who have been killed in the ongoing genocide as of early January, a task that has proven to be increasingly difficult as the Israeli attacks escalate. A page on their website lists many of these artists and archives their stories.

Screengrab from one of Medo Halimy's videos where he showed how he grew plants in the back of their tent.

The presentations consisted of personal anecdotes, episodes and stories as evocative as they were emotionally scarring. Canadian filmmaker Kazik Radwanski, for example, presented the story of Medo Halimy, who started making TikTok videos to show what it is like to live out of a tent with his family following Israel’s genocidal onslaught. However, Halimy claimed to be less interested in capturing their daily hardships than recording how he tries “to live and have some fun” amidst everything. He was fighting depression and struggling to raise some funds for relocating his family—his parents, along with four brothers and a sister—when he started daily blogging and posting on social media. His videos soon went viral, amassing more than 266,000 followers. Halimy's videos contain a dash of dry humour, such as referring to donkey carts as Fast and Furious.

Before October, Halimy studied political science and economics at Al-Azhar University. He had once received an opportunity for a year-long course in Texas, USA, during his school years, where he lived with an American host family with whom he developed a deep bond. He dreamt of returning to the US for further studies and becoming a psychiatrist. On 26th August, he made his last video at a connection cafe, moments after which he succumbed to grave injuries from a nearby Israeli strike. As Radwanski read out the final lines of his presentation, interspersed with a screening of some of Halimy’s high-spirited TikTok videos, he choked and could not go on for a considerable time.

Elham Farah.

Another presentation detailed the life of the eighty-two-year-old musician and educator Elham Farah, who hailed from Gaza’s ancient Christian community that has dwindled to a population of under a thousand in recent years. She had chosen to remain in her ancestral setting when most Christians moved to the West Bank. One of the first music teachers in Gaza, Farah was known in the community for her ever-charming presence, stolid will and her characteristic style of donning large-framed sunglasses and a hat atop her short, fiery orange hair. She also often carried around a purse decorated with tatreez patterns. Though the accordion was Farah’s favourite, she was a master of many instruments, including the violin and organ. Her niece reported that among all the previous Israeli assaults on the Gaza Strip, this was the worst they have ever witnessed.

After the present genocidal offensive commenced, Farah took shelter with hundreds of others in one of the two Catholic churches that served as a refuge for civilians. One day, when Farah left the church to get some fresh air and check the condition of her house, an Israeli sniper positioned on a roof near the house shot her in the leg. The neighbours who tried to reach her were rained with bullets as well. Over the next 24 hours, she bled to death on the streets. “I cannot believe I have to read these lines,” said Roula Said while presenting Farah’s story. Said had herself prepared the text of the presentation, which she concluded by singing the opening lines of Farah’s favourite song that she often sang with her students. It says:

Biktub Ismak Ya Biladi, ‘al shams ilma bit-gheeb

La mali wala wlaadi, ‘Ala Hubik mafee Habib.

(I will write your name oh my country, above the sun that never sets

Not my children nor my wealth, above your love there is no love.)

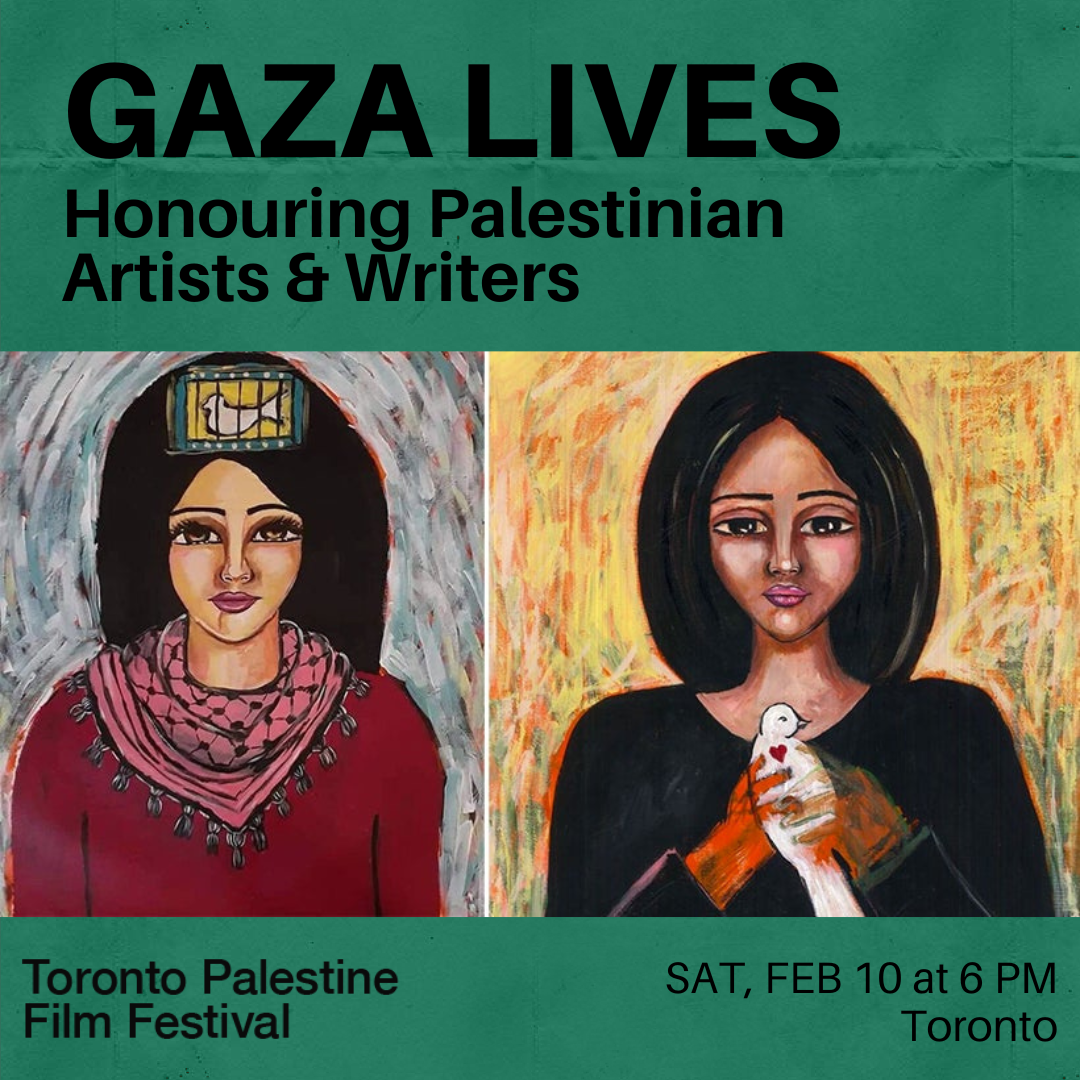

A Gaza Lives poster of an earlier edition held in February 2024.

‘Gaza Lives’ is a profoundly urgent and necessary intervention in these times. It pays tribute to the revolutionary spirit of the artists who continued to express their visions despite all attempts at their dehumanisation by oppressive forces, and also to produce spaces for solidarity through mourning. I urge cultural workers and institutions to bring this project to their respective regions and continue the work of honouring the legacy of Gazan artists across geographies. It is one of the many ways we can start reaffirming the individuality and the infinite lives of all those whom the genocidal Israeli state is still afraid of.

To learn more about reflections on the ongoing Palestinian genocide, read Anoushka Antonnette Mathews’ essay on Abdel Salam Shehada’s Ila Aby (To My Father, 2008), Kshiraja’s essay on Yousef Srouji’s Three Promises (2023), Santasil Mallik’s review of Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba (2024) co-edited by Sandra Barrilaro and Teresa Aranguren and Asim Rafiqui’s recollection of being on ground in Palestine in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead in 2009.