Film as Archive: Abdel Salam Shehada’s Ila Aby (To My Father)

“Remembering, writing and looking at photographs of Palestinian history isn’t only an act of reminiscence—it’s an act of defiance against those who want to wipe out an entire people.”

In the documentary Ila Aby (To My Father, 2008), Palestinian filmmaker Abdel Salam Shehada takes us through a photographic history of the ordinary lives of Palestinian people through archival images, news reports and conversations with photographers who ran photo studios in the 1950s and 1960s.

Students pose for a class photo.

Shehada fondly remembers the excitement preceding the arrival of the photographer who visited his school every year to capture a group photo of each class. The photographer attempted to get everyone still for one second and then click! Once the photograph was taken, the children waited in great anticipation for the final product to arrive. Each eager to see how they had turned out in the picture. He marvels at the fact that “the photo does not get older when we do.”

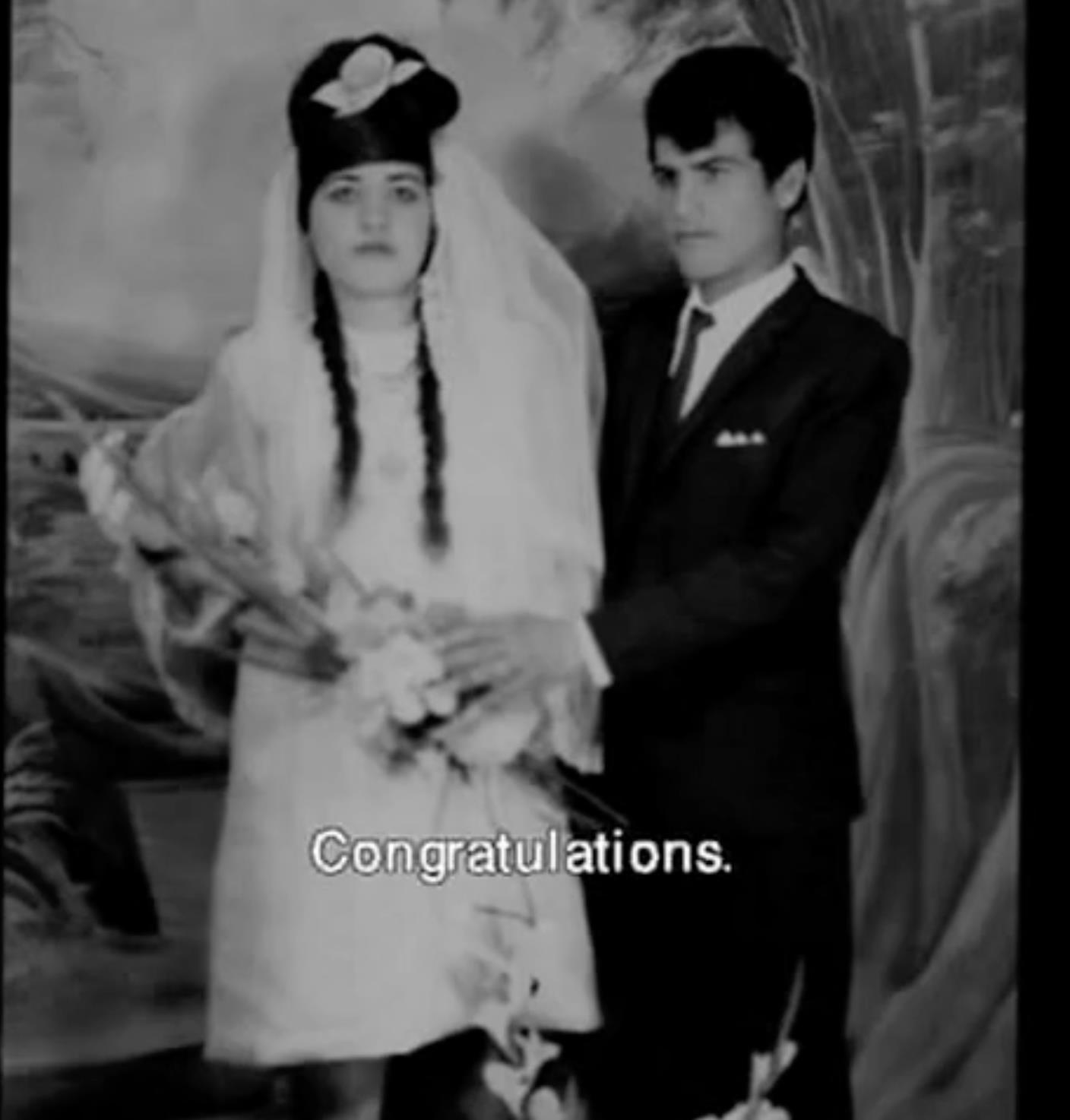

Images from the archives of old photo studios.

Momentarily suspended in time are black-and-white images from photo studios in Rafah. Shehada describes this time, somewhere in the 1960s, as a time “when photographs were beautiful and life was easier.” The backdrop was easily changed as per preference, the expressions altered as per the directions of the photographer and mistakes could be corrected and fixed. Family, friends and lovers posed against backdrops, curiously looking into the camera, evoking some semblance of ‘normalcy.’

Images from the archives of old photo studios.

However, Shehada does not allow the audience to slip into nostalgia for these ‘simpler times.’ Through carefully curated visual montages, he presents an archive of all that has been erased and continues to be erased, seen in the visuals of the burning faces of the people stripped of the agency to live or even imagine ordinary, ‘normal’ lives.

June war of 1967.

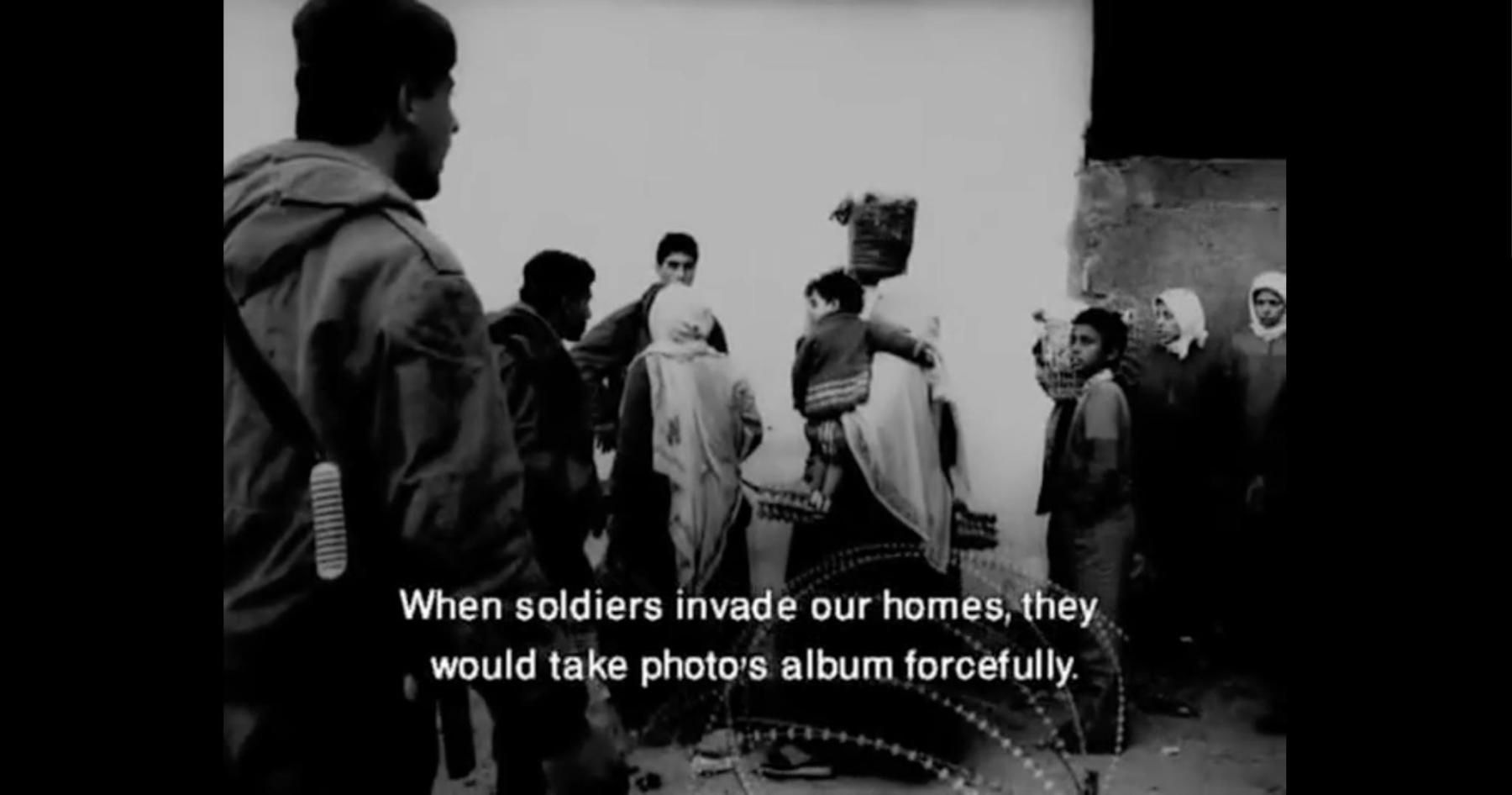

Shehada’s film captures the ever changing relationship that he and many others shared with photography as Palestinians. Recalling the June war of 1967, which he had initially mistaken for an earthquake, he narrates stories of how Israeli soldiers barged into homes and confiscated photographs which they later destroyed and left to burn on the streets. He notes how “with photos becoming a means to identify, people became afraid of photographs.”

June war of 1967 when soldiers invaded homes and destroyed photographs.

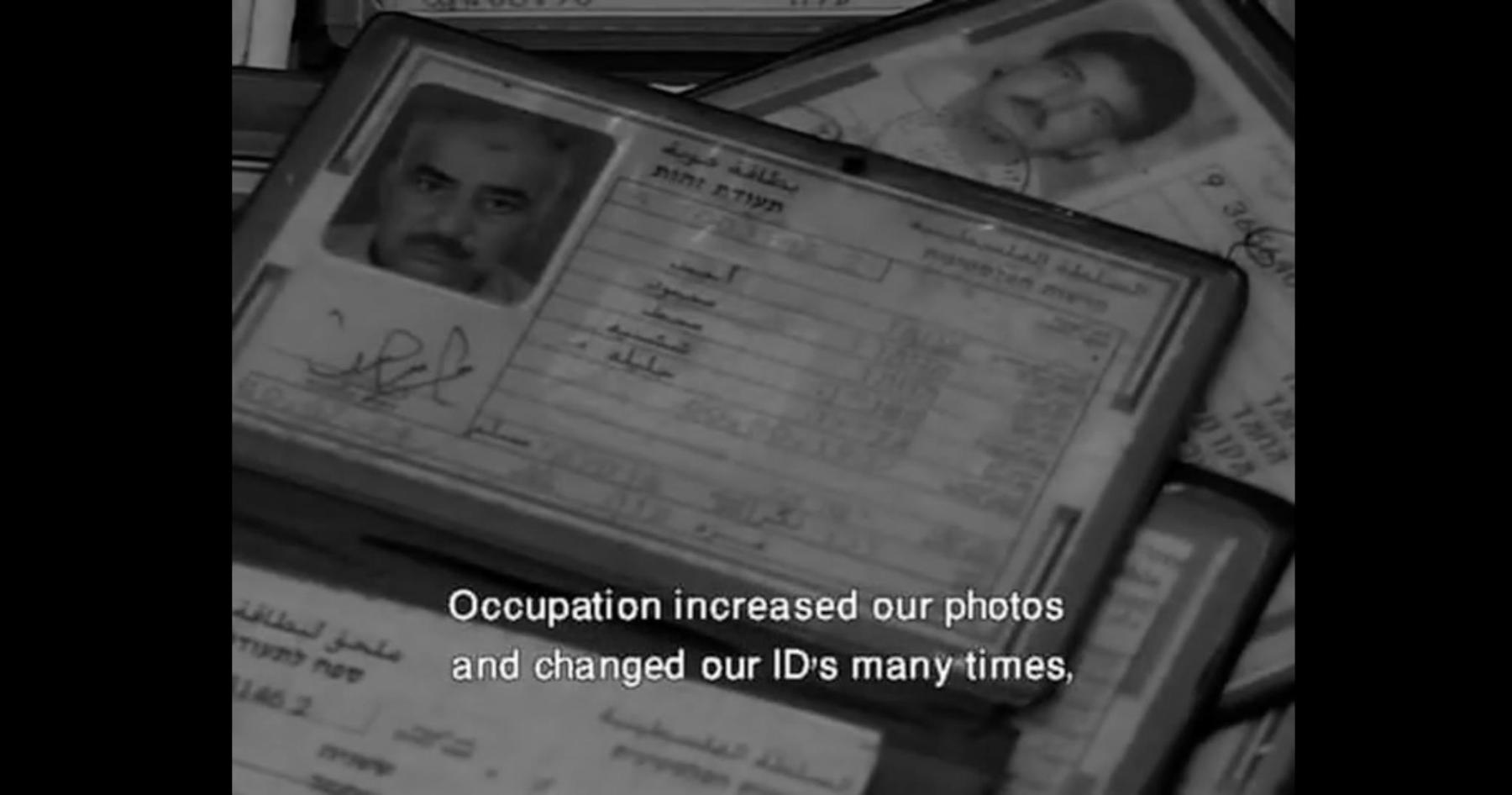

Mass production of ID cards of Palestinians.

Entire camps were squeezed into makeshift studios for the mass production of ID cards. The photographs pasted on the cards were stripped of their cinematic background and the Palestinian subjects of their personhood. The process of photographing was fast even as attention to detail was deemed unnecessary—the idea was to get as many IDs in as little time. No touch-ups, no make-up, no expressions—just photographs that clearly delineate all the features. “They always wanted to see us, what we are wearing, are we getting older or younger or if we became photos?” Shehada adds. Photographs would now allow for one to be identified, tracked and surveyed.

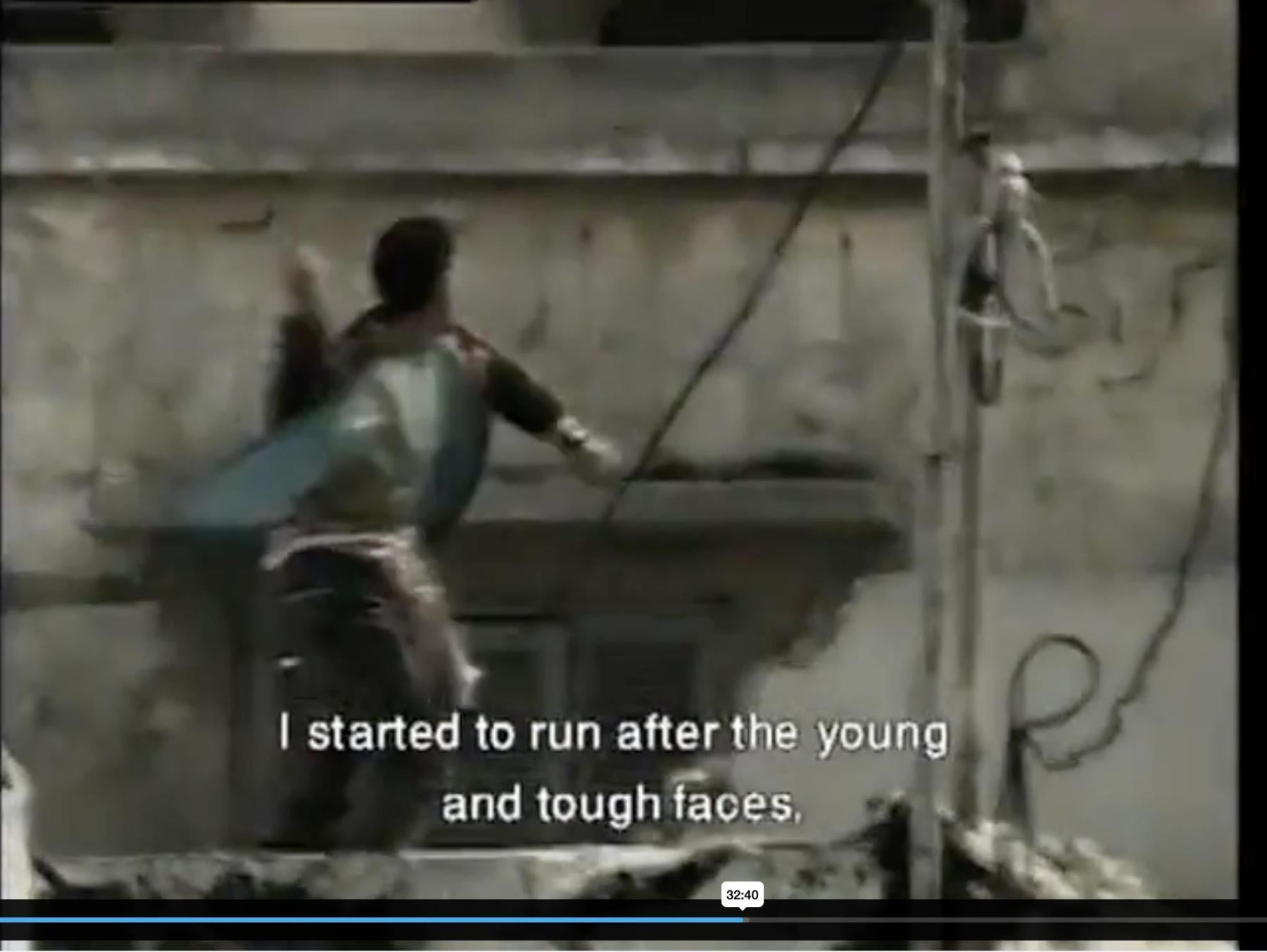

A shot of Abdel Shehada, the filmmaker taking up the camera in the first intifada of 1987.

First taking up the camera during the first intifada of 1987, Shehada shares that with it, he felt a certain sense of power. He looked for freedom in his photos, in the faces of the young boys and girls pelting stones.

A shot of a young boy pelting stones after the first intifada of 1987.

Palestinian mothers hold photographs of their sons who have been killed.

When Shehada comments in the context of Palestine, “There are covers on our faces— we do not know ourselves… They don’t know us; they don't know themselves. Nor do they know these photos; there are too many photos, all of which are alike.” He speaks of Palestinians trying to escape, groups waiting in camps with their suitcases, people falling off trucks and taxis which are already carrying passengers beyond their capacity. The filmmaker comments on “how they began to be photographed from above.” Both guns and cameras, placed at a height, were ready to point and shoot, so now the photographs depict not their everyday lives but their desperation, their attempts to flee.

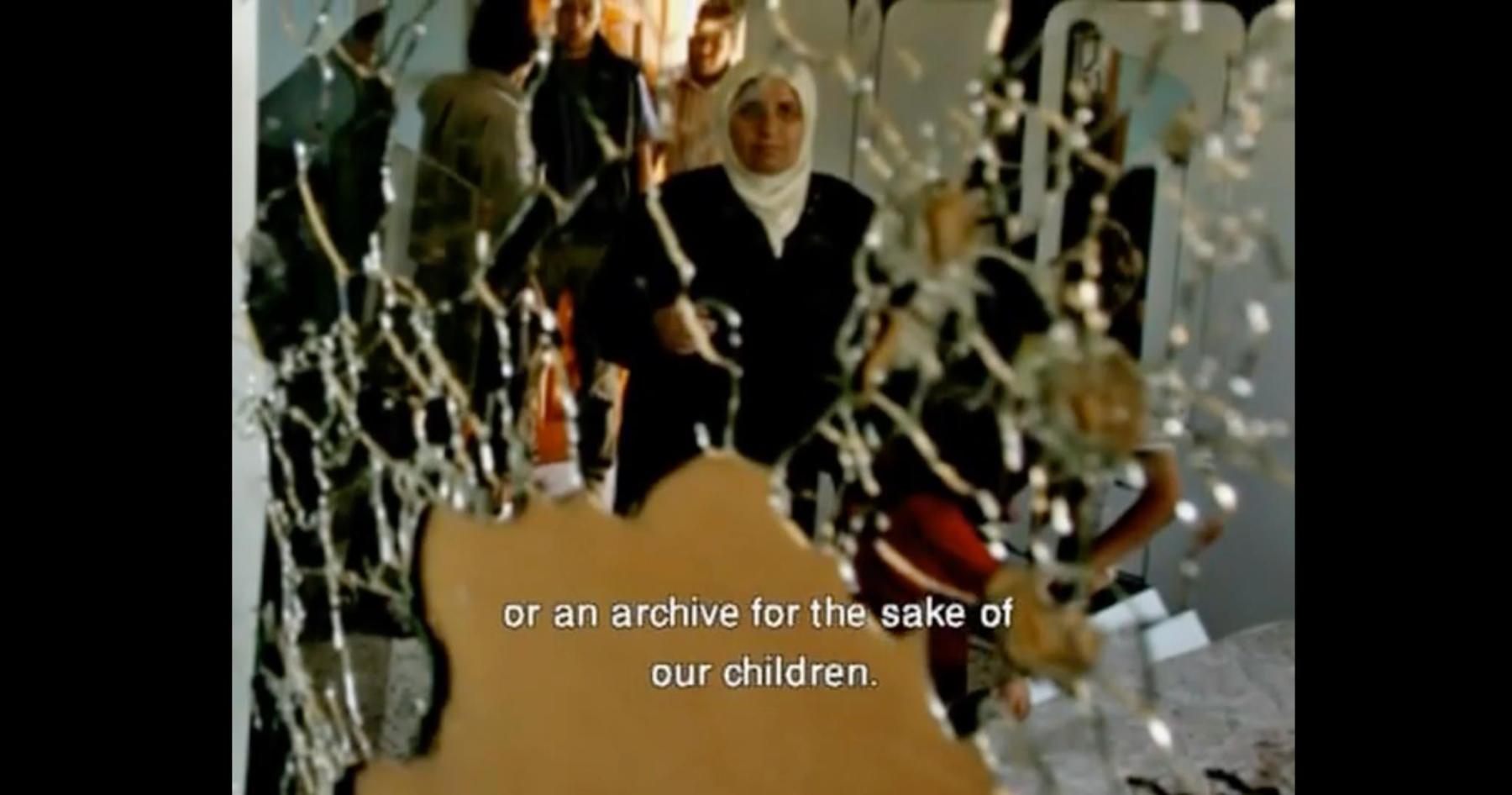

Increased surveillance at camps.

People trying to escape and flee from camps.

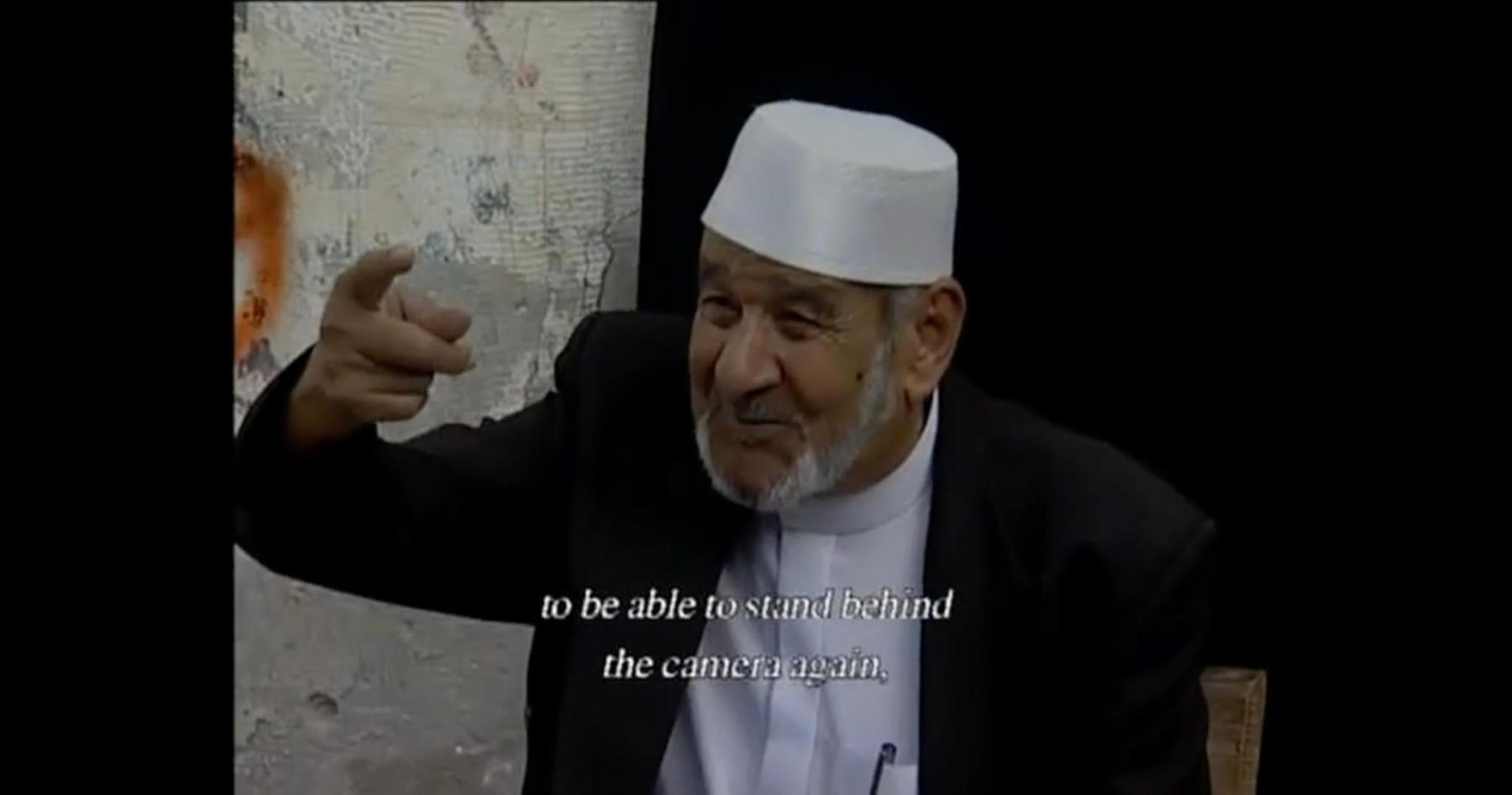

The filmmaker, however, does not end on a note of despair. He revisits whatever remains of the photographers who once brought these studios to life. And though they have lost their photographs, their studios and their subjects, what they do retain is pride and love for their craft. The film points to how photo studios act as preservers of community memory and archives of ordinary life. The photographs from family albums and homes find themselves being held out for collective grieving. In the context of large-scale bombardments in Palestine and the destruction of homes, viewing images from the past helps to build and sustain a collective public memory of Palestinian life.

To learn more about reflections on the ongoing Palestinian genocide, read Kshiraja’s essay on Yousef Srouji’s Three Promises (2023), Santasil Mallik’s review of Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba (2024) co-edited by Sandra Barrilaro and Teresa Aranguren and Asim Rafiqui’s reflections from 2009 while being on ground in Palestine in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead.

All images are stills from Ila Aby (2008) by Abdel Salam Shehada unless mentioned otherwise. Images courtesy of the artist.