On Three Promises: The Palestinians’ Right to a Remembered Presence

Oh no, the memory did not return to him little by little. Instead, it rained down inside his head the way a stone wall collapses, the stones piling up, one upon another.

Ghassan Kanafani, Returning to Haifa (1969)

Rubble in the West Bank during the Second Intifada.

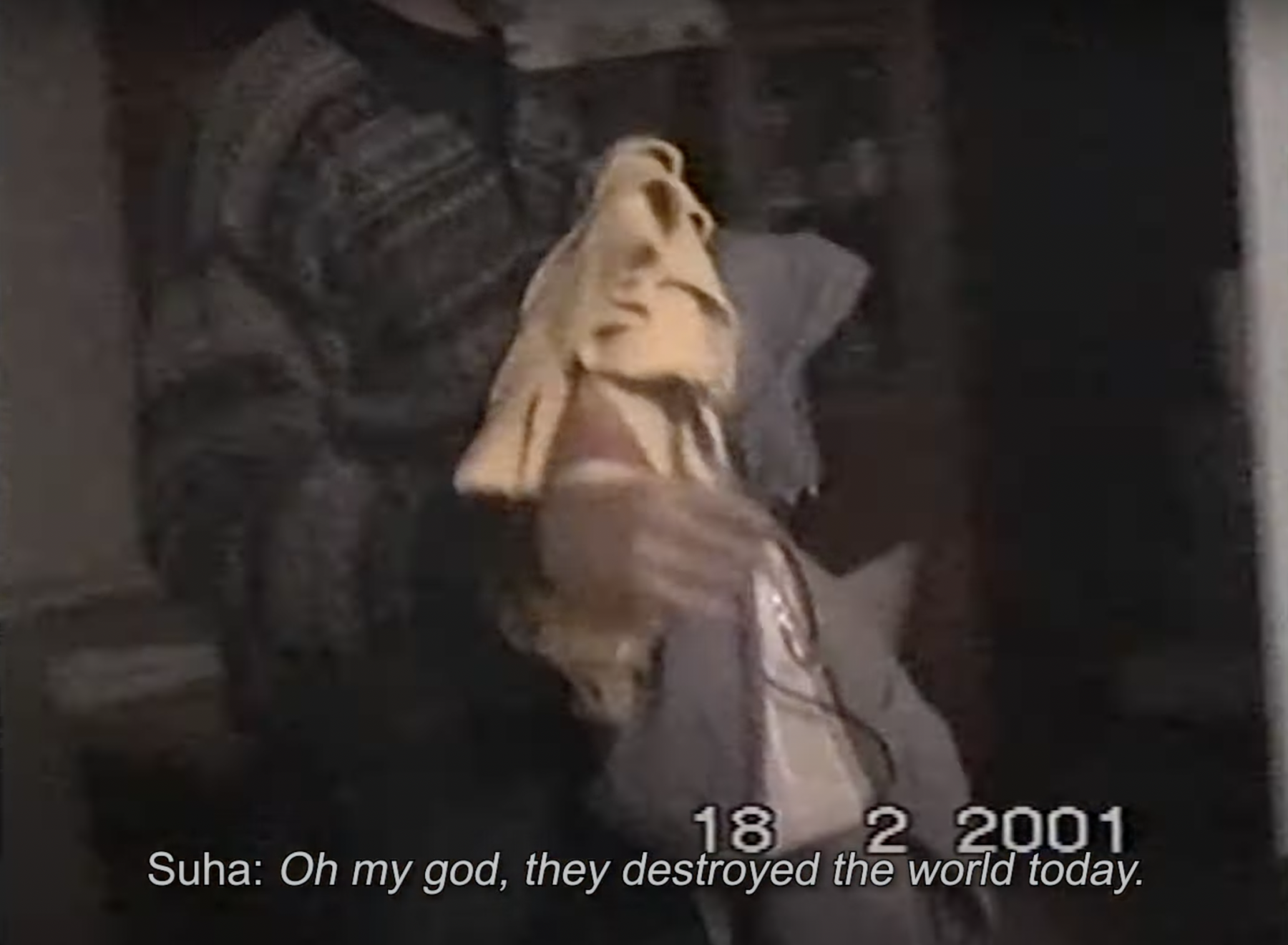

Yousef Srouji’s Three Promises begins with a question to his mother, Suha, who shot most of the footage that makes up the film—why did she keep the tapes hidden away from her children for years? The tapes are of their family’s lives in the occupied West Bank, particularly during Israel’s military onslaught in the early 2000s, during the Second Intifada. Even before Suha ultimately addresses this query on camera, it is her act of revealing what she had been hiding that seems to define how we, as audiences, view these tapes, not so much as a documentary but almost as collective recollection.

Srouji’s mother, Suha, whose home-video footage forms the anchor for the documentary.

In what is an astonishing first film, Srouji weaves together clips from this home video archive and present-day conversations with Suha to retrace his family’s experience of the siege. From animated Christmas celebrations to taking shelter in basements, the film navigates the generational trauma of living under occupation by turning the lens inward. It gently foregrounds the family’s ways of coping with the events—his father Ramzi’s pragmatic composure, Yousef’s ability to crack jokes to distract his family from an ongoing attack, his sister Dima’s refusal to be comforted through platitudes and, perhaps most tellingly, Suha’s urge to capture their lives through the period, even when her camera is met with anger and repudiation. The three promises of the title revolve around three critical, personal moments in their lives that prompt Suha to negotiate with God for the safety of her family in return for leaving their homeland, a promise which she reneges on twice, holding onto her memory of Palestine.

The family is seen moving to their basement in the nights.

It is this memory—collective, not only personal—that echoes through Three Promises, anchoring the audience in the articulation of the Nakba as the the past, the present and the ongoing. It brings to mind how Edward Said described the Palestinian struggle as a battle “...over the right to a remembered presence, and with that presence, the right to possess and reclaim a collective historical reality.”

Yousef, caught by the camera in the first few months of the Second Intifada.

Indeed, with its non-linear editing of the tapes, underscored by the timestamps that hallmark the frames, Three Promises reads to the audience like memory in itself, one that is kept hidden away and comes back sometimes in fragments, but all at the same time. A particularly gut-wrenching moment elucidates how closely intertwined the threads of personal and collective memory are in the film—Suha says that Dima would accuse her of being like Muhammad al-Durrah’s father, who told his son that nothing would happen to him. Twenty-four years later, the footage of the Israeli Defence Forces murdering the twelve-year-old child as his father screamed for help remains one of the defining visuals of the Second Intifada and the occupation.

Beit Jala as seen from the family’s balcony.

In another sobering moment, the family observes from their window as bombs and bullets rain upon the surrounding neighbourhoods. When the terrified children plead to go back inside, Suha tries to calm them down as she says, “we know how these things go.” These things, presumably referring to the military strikes following the intifada, reverberate with the memory of decades-long Israeli occupation of Palestine. When Suha eventually answers Yousef’s initial question, saying that she does not speak about this time in their lives because “we like to forget”, the film transforms from an act of remembrance, of the personal, to an act of reconstruction, of the collective. From an intimate portrayal of the family’s experience of the occupation, the tapes become emblematic of the experience of generations of Palestinians. Through the desire to forget, the film forms a link to a shared past.

The claim to memory is, in many ways, an auxiliary to the claim to a homeland. Where the Israeli government’s imperialist propaganda continues to rely on everything from a decimation of historical fact to a collective amnesia of their ongoing war-crimes, Suha’s reflection provokes the question—who has the right to forget?

There is a certain amnesia that bears mention here, particularly with respect to the South Asian context. The Indian state’s response to the ongoing genocide of the Palestinians betrays our own collective memory of being under colonial occupation, a memory that has long been betrayed by the state’s own occupation of Kashmir. In Three Promises and its act of reconstruction, then, there is perhaps also a call to remember our own shared histories.

To learn more about reflections on the ongoing Palestinian genocide, read Santasil Mallik’s review of Against Erasure: A Photographic Memory of Palestine before the Nakba (2024) co-edited by Sandra Barrilaro and Teresa Aranguren and Asim Rafiqui’s reflections from 2009 while being on ground in Palestine in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead.

All images are stills from Three Promises (2023) by Yousef Srouji. Images courtesy of the artist.