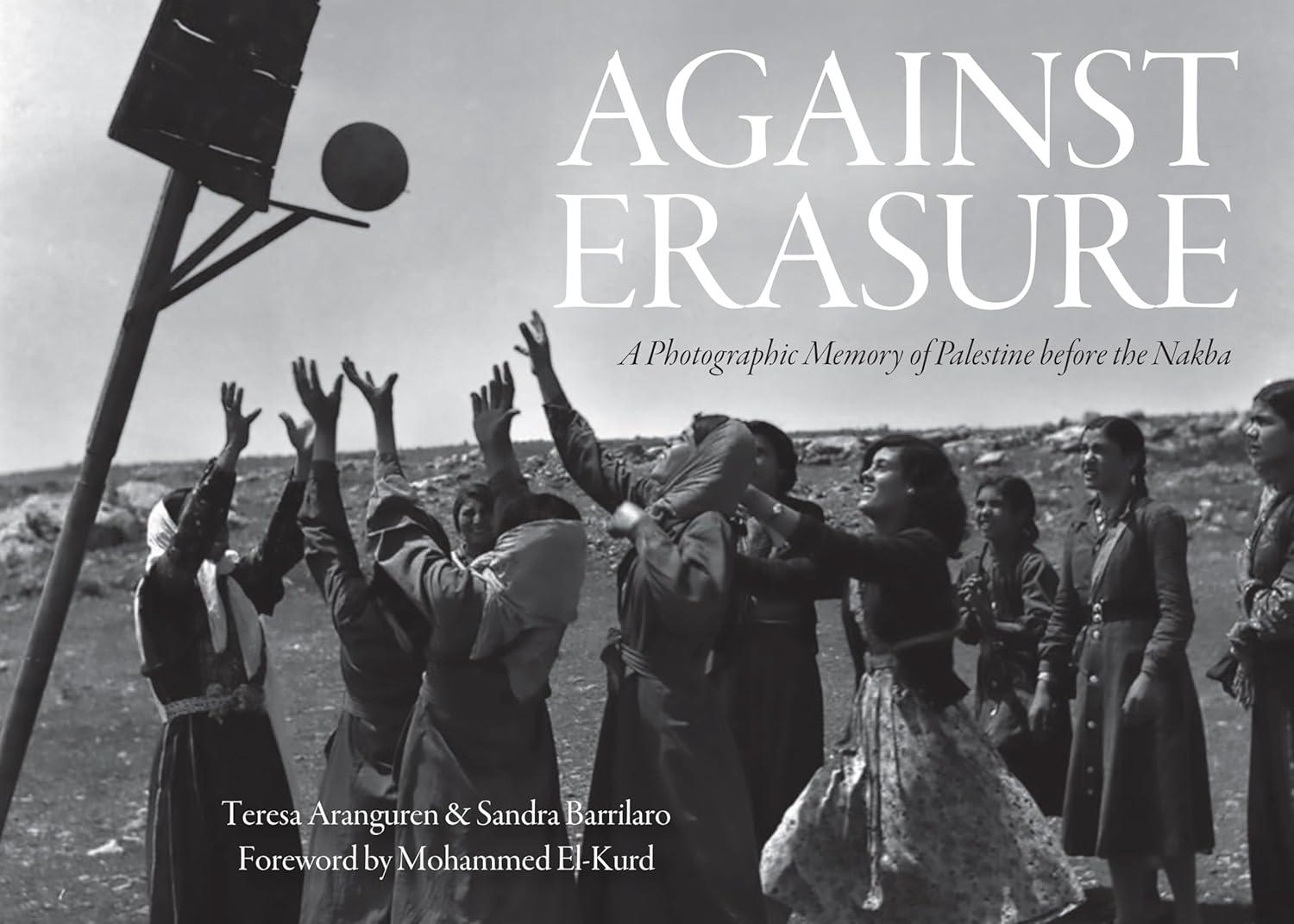

Against Erasure: To Remember is to Reconstruct

Book Cover.

For years, Palestinian historian Johnny Mansour has been amassing oral histories, photographs and textual documents from people’s personal and public archives in his hometown, Haifa, as well as ‘Akka (Acre), Shafa ‘Amr, Nazareth and al-Jalil (Galilee). He intends to chronicle life before and after the 1948 Nakba, when Zionist militias unduly exterminated the majority of these regions’ Arab inhabitants. In the English-Arabic bilingual photo book Against Erasure (2024), co-editors Sandra Barrilaro and Teresa Aranguren take Mansour’s collection as a starting point to compile previously unpublished photographs of Palestine encompassing the period from 1898 to 1948. Before meeting with Mansour in Haifa, the co-editors also travelled to Ramallah, Bethlehem and Jerusalem during the summer of 2014 in search of family albums. Eventually, they came upon the photographic archive of Jerusalem’s American Colony Hotel known as the Matson Collection, which houses more than 22,000 negatives and glass plates now digitised and openly accessible on the US Library of Congress website.

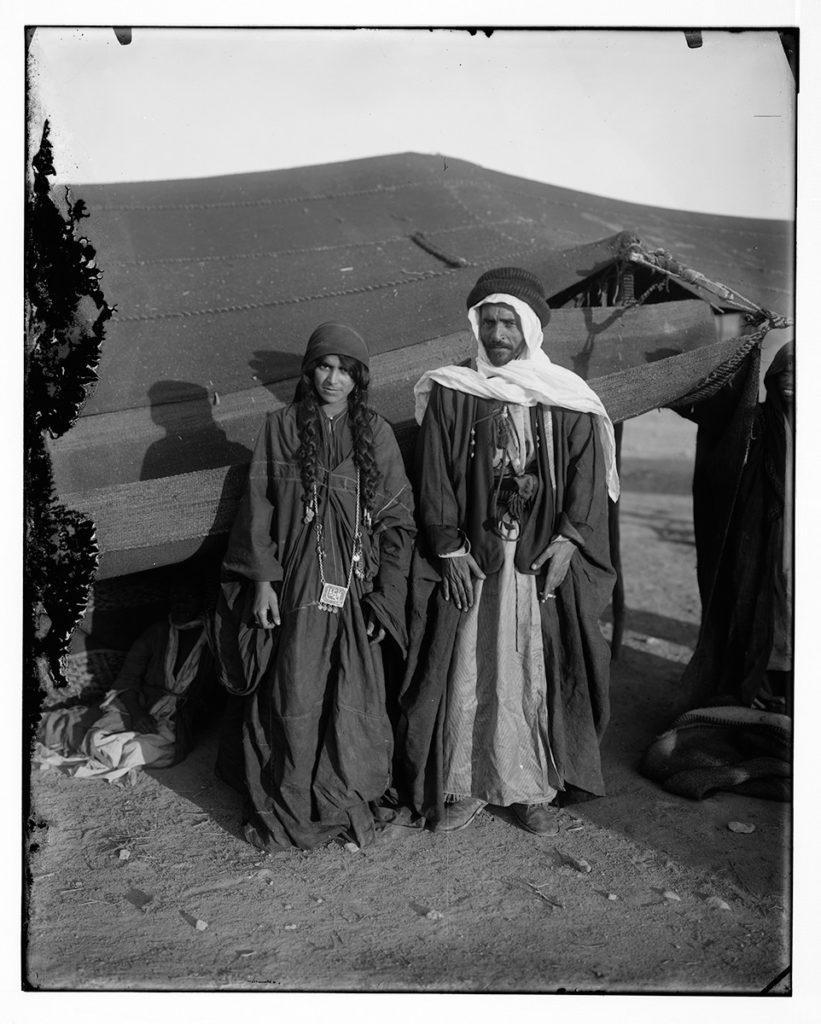

A Bedouin couple next to their tent, 1898-1914.

As we recently entered into an entire year of witnessing the ongoing genocide by the Israeli state and as our news screens continue to bleed with visuals of insurmountable barbarity in Palestine and now Lebanon, Against Erasure assembles an image archive that reinstates Palestinians’ claim to their ancestral land and cultural heritage. The book contains family studio portraits of Haifa’s “urban bourgeoisie,” profiles of Bedouins, monks and church leaders in traditional dress, group pictures of diplomats and government officials under the British Mandate, photographs of its agricultural population at work or workers in various sectors, including health, railway, aviation, sports, and quotidian images like that of an open-air cinema screening in the village of Halhul or a lemonade seller during a festival in southern Palestine. By itself, this collection of images refutes the time-honed Zionist occupation warcry: “a land without a people for a people without a land,” even as Barrilaro confesses to abetting the photographs’ “documentary value” by reproducing them along with the surrounding black frame of the films, cardboard mounts, numbering details, stains and smirches on the pages, as well as annotations scribbled on the margins of the prints.

British Engineers standing in front of the rubble of houses blown up with dynamite in Jaffa during the Arab protests in the summer of 1936.

The book is profoundly relevant in retracing a period in Palestinian history before the Nakba. While discussing her novel The Parisian (2018)—set in the period between the end of the Ottoman rule and the beginnings of Palestinian nationalism in the 1930s—British-Palestinian author Isabella Hammad, who grew up abroad, states that she decided to focus on the pre-1948 history of the region to question her assumption that Palestine’s history began with the Nakba. Barrilaro and Aranguren’s endeavour aligns with a similar intent historiographically, focusing on a long history of the nexus between British colonialism and Zionist occupation, and Palestinian resistance to both in the first half of the twentieth century. In an introductory essay to the book, political theorist Bichara Khader enumerates the early history of Zionist settlers in the region since Ottoman rule, covering watershed events like the acquisition of land in Jaffa by the banking giant Baron Rothschild in the 1880s, the role of the Jewish National Fund in financing colonies, the Balfour Declaration in 1917, and significantly, the waves of anti-British and anti-Zionist revolt in the 1930s. Correspondingly, the photographs not only show the multicultural fabric of Palestine but also document the people’s history of anti-colonial insurgency and rebellion, serving as what Barrilaro calls the “reminder of the human condition of a society that cannot be erased.”

Boatmen and stevedores as they prepare to resume work in Jaffa.

One photograph from the book reveals a group of boatmen and stevedores posing for the camera in the port of Jaffa in July 1937 as they resume work after almost a year-long strike against the British administration. This strike, marking the onset of the Arab Revolt from 1936 to 1939, intensively paralysed all commercial activities in Mandatory Palestine. The workers in the photograph, with several fists raised in the crowd, are a symbol of the undying determination and resoluteness of the Palestinians’ fight for justice. Indeed, the iconographies of resistance such as the keffiyeh and ‘tatreez’ weave patterns arose during the early years of Palestinian nationalism precisely from different working-class backgrounds. There are other more everyday photographs, like one showing a group of women studying in the gardens of the Schmidt’s Girl College in Jerusalem on one sunny afternoon in 1942 or a school trip photograph of young female students with their teacher by the Jordan River. These scenes affect the viewers with a self-evidential force as they constellate with the ongoing present, a time when all of the universities in the Gaza Strip have been turned into rubble by the Israeli Defence Force.

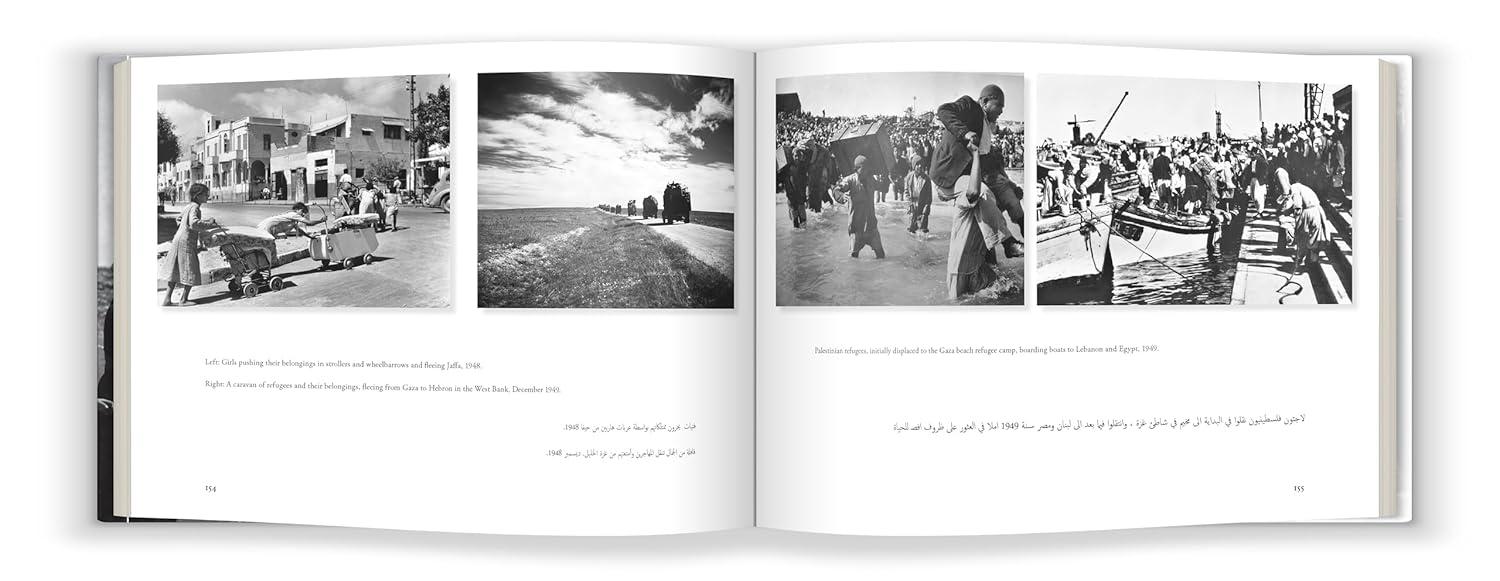

Prefacing the book, Mansour writes that the function of photographs and oral narratives as research tools should not be limited to recording the past. Instead, their deployment should radiate a sense of the future, a future with “a strong possibility of returning” to the homeland. Mansour addresses a double-fold relationship with the images. On the one hand, they hold “an unrepeatable reality” in static terms, but, at the same time, they invite the viewers to reconstruct the spirit that connects Palestinians to their land. The heterogeneity of the book’s archival materials effectively makes space for such reconstruction, interweaving images with Walid Khalidi’s list of 418 Palestinian villages destroyed in the Nakba, census reports of agriculture and education before 1948, passport and graduation certificates, or poems by Mahmoud Darwish and Fadwa Tuqan, among other forms of evidence.

A spread from Against Erasure.

In the book Before the Diaspora (1984), Walid Khalidi assembles 500 photographs of Palestinian life before the Nakba from various public and private collections. Every image is individually researched and identified by time, place and context. Against Erasure, on the other hand, is more free-flowing in its arrangement and captioning of the pictures. It professes to add “a grain of sand” to the pre-1948 archive by presenting an image collection that acknowledges the multiple facets of Palestinian history untethered to the idea of displacement as its genesis. Mohammed el-Kurd particularly notes in the book’s ‘Foreword’ that “Palestine’s history does not begin in fleeing.” He adds that the counter-archival compilation is “as illuminating as it is incomplete,” for there are conversations to be exchanged with the older generations and people around us to ensure that the victims, survivors and resistors of the present-day Nakba amidst us all are not reduced to numbers in sweeping headlines.

As South Asians with numerous genocides breathing down the necks of our shared historical anima, we need more cross-contextually situated conversations in our circles, communities and families about Palestine. It is not only to animate a larger perspective of the region’s history in light of the present but also to measure our complacency and complicity in the genocidal economy. And the book presents itself provocatively as a necessary opening wedge toward such directions.

To learn more about images chronicling the Palestinian genocide, read Asim Rafiqui’s two-part essay on his experience of being a journalist in Gaza in 2009. To learn more about family albums as personal and public archives in the South Asian context, read Sukanya Deb’s essay on Siva Sai Jeevanatham’s photographic series In the Same River (2017–21).

All images are from the photo book Against Erasure (2024). Images courtesy of the authors.