Gaza: Love, Curse

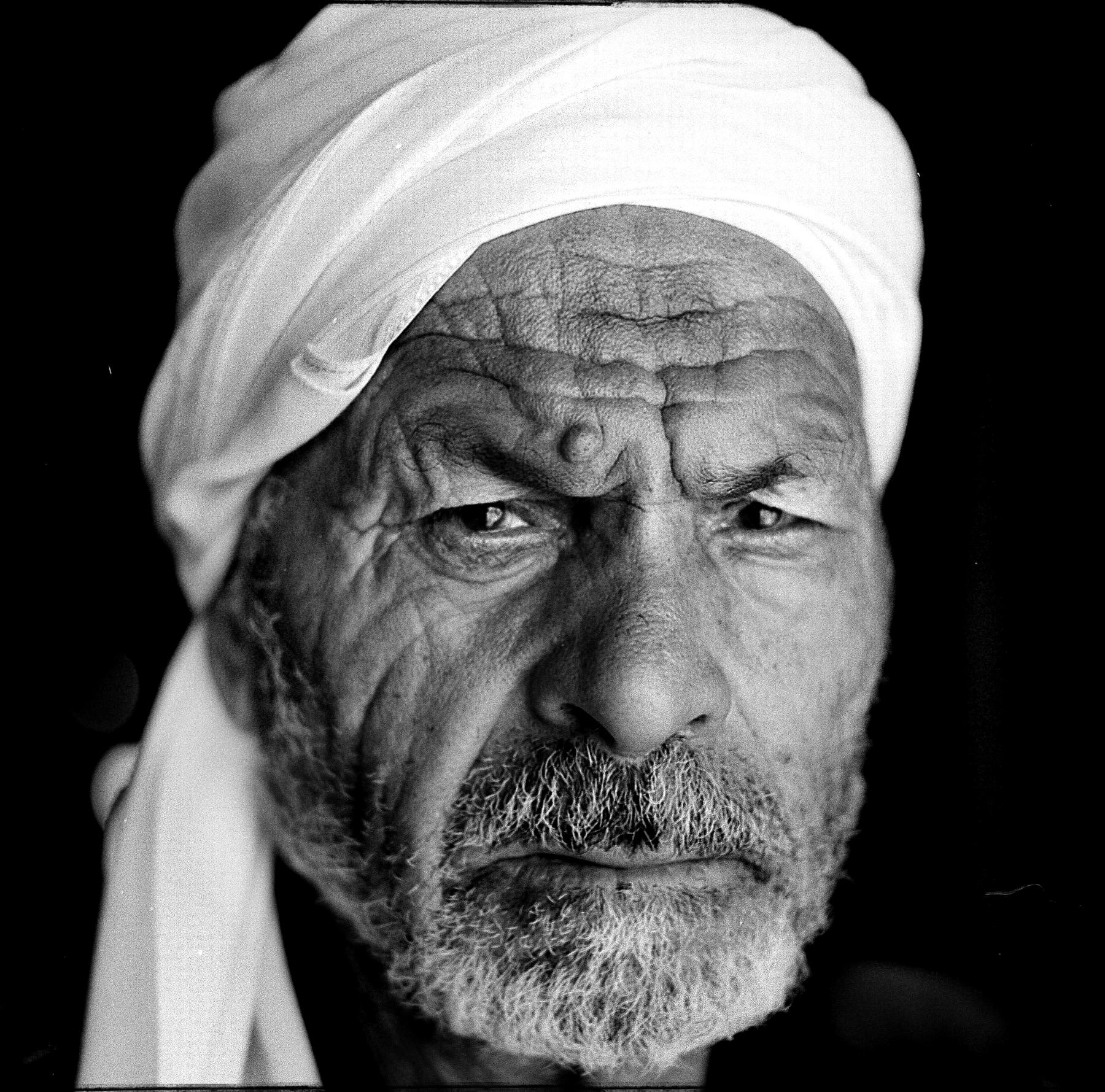

Ismail Ibrahim Abu Eida.

Ismail Ibrahim Abu Eida was walking alone near the rubble of his family home, lost in thought. When he noticed me standing close by, he merely nodded and said nothing. I stood there looking at him stumble and trip across the pile of rubble that had once been his home. A lone figure amongst thousands of lonely figures all over Gaza who were at that very moment quietly, resignedly stumbling and tripping across the rubble of their own lives. I wanted to talk to him about what was going through his mind, but he seemed reluctant, even a little embarrassed. “What can I tell you that others have not?” he said quietly. And he was right.

Abu Eida's pain—the loss of his life's work, the displacement of his family and the ruination of his livelihood—was an oft-repeated occurrence in this land. Tens of thousands had already suffered it, and it was inevitable, given the entrenched ideas and ideals that perpetuate this conflict, that tens of thousands more are destined to do so in the future. In this land of pain, where everyone has experienced the gravest of loss, it has become difficult to express individual suffering or ask for compassion. In a life that must accept as ‘normal’ the sudden and violent erasure of all that one holds dear, a life in which you console your neighbour, knowing full well that someday they will be consoling you, you no longer speak about your sorrows. You no longer share your burden because others are so crushed under their own. In a life of collective punishment and suffering, your scars and sufferings are starkly your own to confront and tolerate.

Abu Eida was fortunate. No one had died. His family had been displaced to a UN refugee centre, and he was sleeping on a mattress in a shipping container on the family property. With a voice that was severely controlled, he explained to me how tanks and bulldozers had forced him to flee and levelled everything he had built over the course of his life, including his family’s orange groves. Then he invited me for tea. He had only one cup. After spending some time digging in the rubble, he produced a second cup—broken but usable. He had no place for me to sit, but a shout to a friend down the road produced a three-legged plastic chair. I protested this kindness, but he would not hear of it, reminding me that I was his guest. “It is our way, Mr. Rafiqui,” he insisted, as he made himself comfortable in the dirt, “to honour our guests—and to remind ourselves of the things within us which tanks and missiles cannot destroy.”

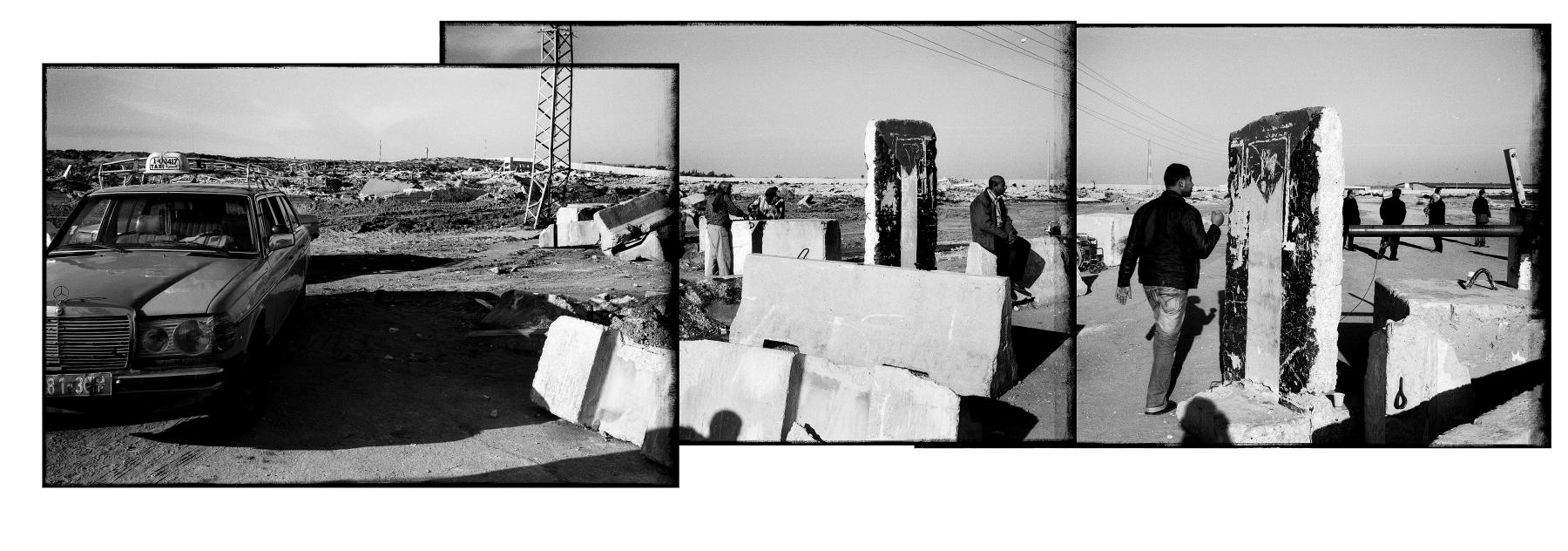

Erez, near Beit Hanoun, Gaza. A view of the wall that separates Gaza from Israel as seen from the Erez crossing. Taxi drivers and a few diplomatic and press travelers wait to get permission to walk towards the Israeli checkpoint.

As the day grew hotter, the mist that shrouded the citrus groves lifted, revealing what had once been the Jabaliya industrial zone. Abu Eida pointed toward Israel. I could see a wire fence and the silhouettes of soldiers walking along it. Israeli farmers had begun returning to their fields that morning as jeeps carrying soldiers raced back and forth along the border areas. Snipers kept an eye on the few Palestinians who dared to return to their lands. Despite the cease-fire in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead in 2009, Gazan farmers were being shot and killed at random. “I used to work in Israel,” Abu Eida said. “But that was a different time, a different world.”

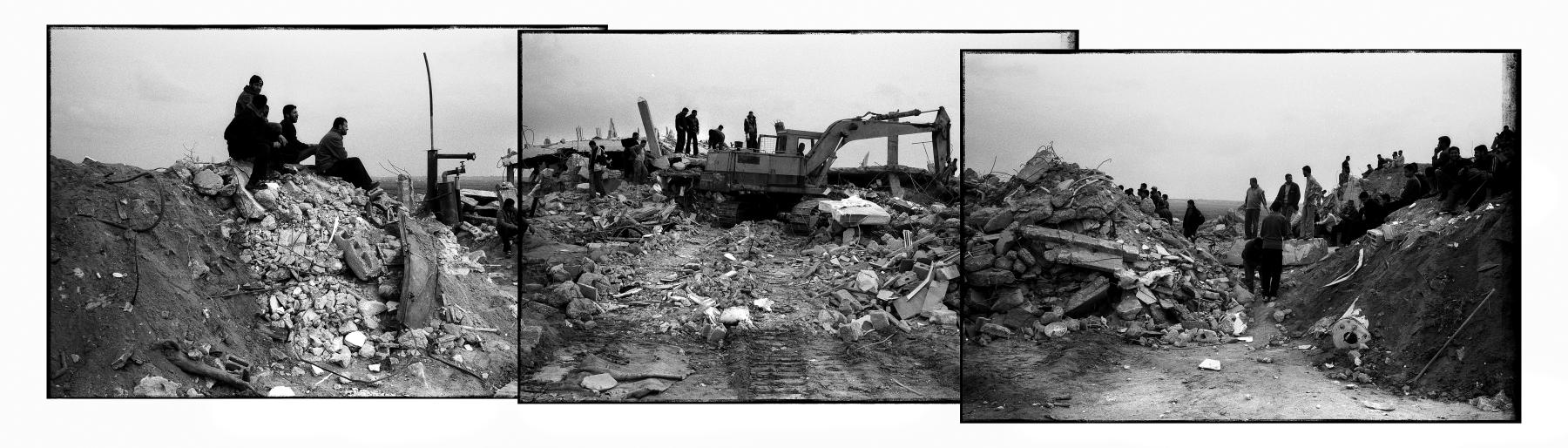

This world, the one whose remains surrounded us that morning, now lay in a shroud of dust raised by the hundreds of hands salvaging valuables from the remains of their homes, factories, stores and farmlands. As I looked up from my cup of tea and out towards the scarred landscape, I could see people sifting through the rubble, searching for bodies, salvaging remains of machinery, consoling their children, or just sitting amongst the ruins of their homes. It struck me that, indeed, how fortunate the dead were, who had at least, as Plato said, seen the end of war. The living, however, go on and suffer its horrors, carry its burdens, tolerate its indignities, appease its sorrows and accept its cruellest gift—the death of loved ones.

Later that morning, I finally made my first photograph. A portrait of Abu Eida. He was reluctant and shy and insisted I look to those who have suffered more. He turned and pointed a finger to where I could see a family searching for the remains of a patriarch. The bulldozer roared and clawed mercilessly against the pile of ruins, churning up metal, concrete, electrical wiring, toys, clothing and whatever else its massive jaws caught in their broad sweeps. Around it sat many family members and friends, patiently watching the bulldozer work, prepared for the moment the body was discovered. “How do they know if someone is still trapped in there?” I asked. Abu Eida looked at me somewhat bemused and said: “You can smell it!"

Jabal Kashif, Gaza City. Searching for remains of family members.

There were no camera crews at the site, no photojournalists waiting to capture the moment. It was just one body, one individual, being searched for. The "hot" news stories were elsewhere that morning and will be elsewhere the day after. But these searches, these sorrows, and the days without those who were once so close, so needed, will go on. As I stood on a small hill and watched the bulldozer tear away at the collapsed walls of the house, I was struck with the realisation that even when the world's attention falls on them, the Gazans are most distant, misunderstood and isolated from us. The world comes to them, asking them to be either the hate-filled militants out to destroy Israel or the innocent victims of Israel's fanaticism. In the process, it denudes them of their ordinariness, frailty and flawed humanity. In its attention, the world ghettoises them, refusing them their history, politics, memories and agendas. Gone are their love affairs, their family feuds, their fears and hopes for their children's futures, their infidelities, their ambitions, their material desires, their days on the beach, their care for their elderly, their gentleness towards strangers, their love of food, their eye for the perfect coffee bean, their undying and near familial love of the olive tree and their sense of connectedness with the land.

This land called Gaza—a love and a curse.

In case you missed the first part of this essay, you can read it here.

To learn more about ways in which to think through the representation of the ongoing Palestinian genocide, read Radhika Saraf’s three-part essay unpacking W.E.B. Du Bois’ notion of the colour line.

Images courtesy of Asim Rafiqui, 2009. This work was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, Washington D.C. USA.