Gaza's Endless Silences: On the Politics of Visibility

“And what projects are you working on at the moment?”

“An exhibition…and…I’m working on the completion of a new book, something very close to my heart.”

“What’s it about?” “The Palestinians.”

“There was a rather long silence…my friend looked at me with a slightly sad smile and said, “Sure, why not! But don’t you think the subject’s a bit dated? Look, I’ve taken photographs of the Palestinians too, especially in the refugee camps…it's really sad! But these days, who’s interested in people who eat off the ground with their hands? And then there’s all that terrorism…I’d have thought you’d be better off using your energy and capabilities on something more worthwhile!”

“The Swiss photographer Jean Mohr in conversation with a fellow journalist. Quoted in Edward Said and Jean Mohr's book After the Last Sky: Palestinian Lives (1999).

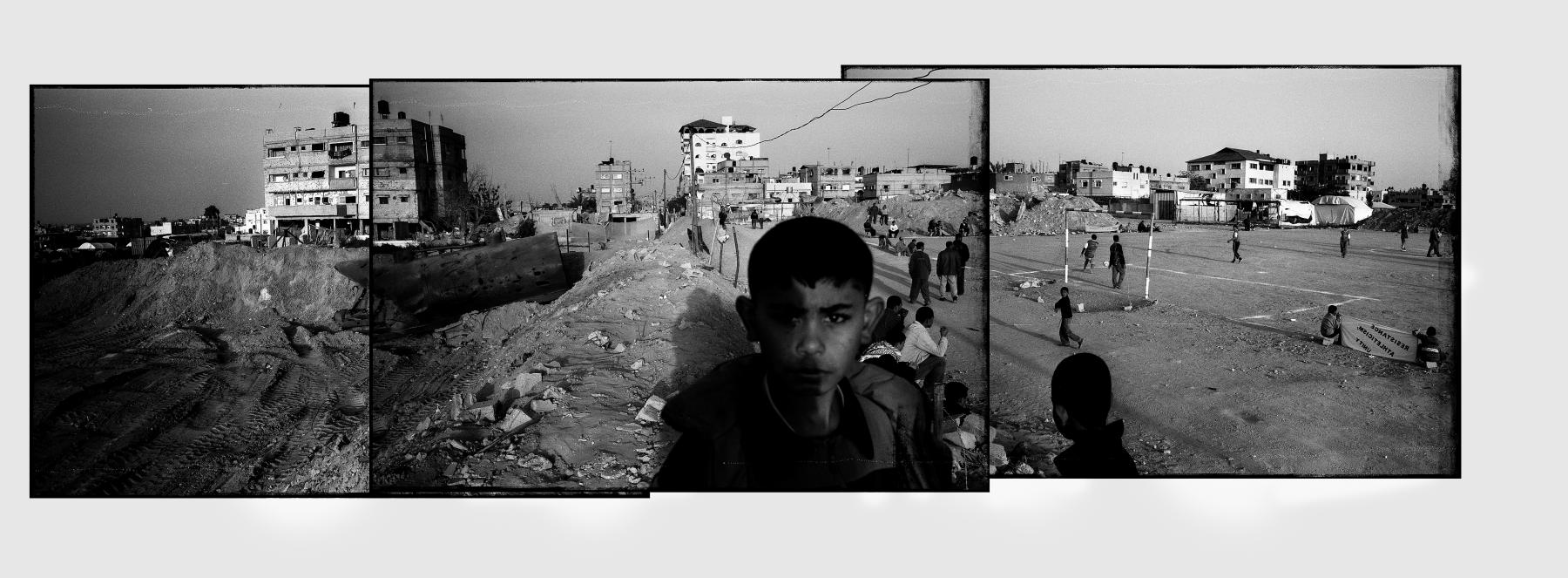

Jabaliya refugee camp, Gaza City.

Edward Said, the Palestinian intellectual, writer and one of the most eloquent voices to have argued for justice for Palestinians, once described Palestine as one of the cruelest and most thankless causes to uphold. If you find yourself committed to it, you can expect nothing but opprobrium, abuse and ostracism. This perhaps explains why most independent photographers arriving in Palestine carry with them the realisation that much, if not all, of their work will be ignored and largely unpublished. This is not only because Gaza and the West Bank are among the world’s most thoroughly photographed human tragedies but also because speaking of the Palestinians as real people with real suffering remains near impossible.

The story of Palestinians has been effectively reduced to that of "terrorism," "extremism," or of them as "instigators of violence." Their rights and demands for justice are drowned out by a shrill insistence on Israel's infinite innocence, the normalisation of a colonial settlement project based on racial apartheid, and the planned displacement and murder of millions in the name of a "right to defend." The responsibility for the violence—by Western political leaders and media—has always been placed on the weak, unarmed and repeatedly defeated shoulders of the Palestinians. Those who try to reveal a different reality, raise questions about the myth of Israeli innocence, or question the assumption of Palestinian mendacity come to Palestine armed not with major assignments but with convictions that are personal and individual.

And they usually come alone, as I did when I arrived at the gates of Rafah, Egypt—the only crossing into Rafah, Gaza, in the wake of Operation Cast Lead in 2009. By the time I argued my way into Gaza, a way repeatedly blocked first by the Israelis and then by the Egyptians, I found myself amidst the devastation of the latest Israel assault on Gaza that Hamas called Battle of al-Furqan (الـــفرقـــان مـــعركـــة), but which was referred to by Western media and the Israelis as Operation Cast Lead.

The Israeli assault on Gaza began on the last day of Hanukkah on 27 December 2008 and eventually left nearly 1400 dead, thousands injured and tens of thousands displaced. Every major international TV news channel, daily newspaper and weekly magazine covered it. Their cameramen, on-screen personalities, photographers, directors, fixers and coordinators stormed the walls of Gaza in a rush to film, edit, transmit and broadcast the events as they unfolded. On any given day, at any given hour, dozens of videographers and photojournalists could be seen in the hallways of Gaza's famous Al-Diera Hotel speaking anxiously into their mobile phones or sitting at tables in the restaurants, hunched over their laptops, cursing the slow internet connections and desperately transmitting their latest images. And when they were not scoffing down a quick meal, they were furtively discussing plans with their local minders or rushing towards their waiting cars to get to a "hot" location. Amidst this mob of media, I, with my little film cameras and a small grant that gave me the freedom to work at my own pace, found myself apart, confused and more alone than ever before. How would what I came to say be heard over this noise?

The Egyptian-Gaza border, Rafah, Gaza. Young Palestinian boys watch the first football game in the city since the declaration of the ceasefire after Operation Cast Lead. The game, being played along the heavily bombarded, Egyptian-Rafah border area, was meant to raise awareness of the struggles and suffering of Rafah's children.The infamous Gaza tunnels are mostly built along this area and were the stated reasons for the heavy bombardment.

My first time in Gaza was in the summer of 2003. I was a novice photographer who went because Edward Said wrote a small response to an email I sent him and encouraged me to go. I then kept coming back, particularly to the southern Gaza city of Rafah, where I lived (on and off) and worked for nearly four years. The settlers were still in Gaza then, but so were activists from the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) working alongside Palestinian social workers and human rights organisations. Home demolitions were frequent along the Rafah-Egypt border as bulldozers tore down Palestinian homes to make way for the massive steel wall that was being constructed along Rafah’s border with Egypt. Tank patrols would terrorise residents living along the border, and there would be frequent firing into these neighbourhoods, resulting in deaths and the maiming of residents.

On the one hand, dozens of courageous Palestinian photographers, videographers and journalists were doggedly documenting the crushing existence of the Gazans and the terrifying economic and military violence against them. Alongside them, many international photojournalists kept photographing the "militants" and the "fanatics" as if to provide the facts that would maintain what Saree Makdisi has called a language that prevents us from recognising what is really going on in the Middle East. As a young freelance photojournalist, I, too, documented my fair share of funerals, Hamas marches and families salvaging their belongings from the ruins of their destroyed houses in this surrounding territory, making several trips between 2003 and 2007. It was exciting, but it was predictable. It was scary, but it felt like it was relevant. And then I stopped coming.

I felt that after four years of coming to Gaza, I had nothing to add and was merely yet another international photographer with privileged access to Western media outlets, reproducing and documenting what was already being done by the Palestinians themselves. After all, I worked with the assistance and advice of Palestinian journalists and locals, whose courage and creativity were transformed into my own as I edited my images, wrote my captions and forwarded them to my agency in Paris. It became difficult not to see how my work and my access to the corridors of media organisations was another stone in the wall that ensured Palestinian voices and representations did not make it into the journals and newspapers.

Gaza City. Men pick through the remains of the destroyed Ministry of the Interior, Ministry for Social Services and the Ministry of Labor. The site also included the now destroyed Office of Pensions (formal name?) that contained the records of pension payments owed to Palestinian workers from Israeli employers.

The Palestinians, too, were trapped: beholden to the demands of international wire agencies, they were discouraged from producing engaged, long-term and human-centred works. Instead, they had only to create images of Palestinian violence and suffering that the editors sitting in New York, Paris or London wanted to see. Every image they managed to sell meant a cash payment. It was how they kept a roof over their heads and food on their children's plates. They photographed what was sold in the Western capitals. And Palestinian humanity, generosity, sensitivity, creativity and resilience were not something the world seemed ready to understand or accept.

But this was not the only reason I stopped. I also realised that nothing I could see or show came even close to the scale and depth of the horror of Gaza. In retrospect, I realise that putting down my camera was an act of surrender by a young photographer frustrated by his inability to adequately represent the gravity, scale and horrors of the sufferings he saw around him, and the calculated callousness and indifference with which it was cleansed and misrepresented by journalists and the editors they worked for. By the end of 2007, I had put away my camera and cancelled further travel plans.

But now, in the fading winter days of February 2009, I was back again, and as I walked through the devastation left in the aftermath of Operation Cast Lead, I was struck by how familiar it all looked. The scale was more extensive than anything that I could remember. Still, its consequences were familiar: the bombed homes, the displaced families, the tank-track torn olive and citrus groves, the stunned relatives of the dead, the funerals, the screams of mothers, the corpses of children, the Hamas marches, the victory songs, the numbing buzz of the pilotless drones overhead, the children scavenging amongst ruins, the sirens of the ambulances, the men on donkey carts carrying debris to nowhere, and that constant, distant human wail of a life torn apart or a hope torn asunder.

And so, here I was again, as I had been here before, witnessing scenes that were remarkably similar to those I had seen previously. As some of the world's best photojournalists scrambled to capture the devastation for the world's audience, I found that I still had nothing new to say, and by the second day, I once again put away my cameras and stopped taking pictures.

And then I met Ismail Ibrahim Abu Eida.

To read the second part of this essay, please click here.

To read more about reflections on image-making in the context of Palestine, read Najrin Islam’s three-part essay on photography and filmmaking practices of Palestinian filmmakers, Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Abdallah Al-Khatib’s Little Palestine: Diary of a Siege (2021) and Kamayani Sharma’s conversation with photographers Maen Hammad and Dina Saleem.

Images courtesy of Asim Rafiqui, 2009. This work was supported by a grant from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, Washington D.C. USA.