Canned Laughter: On Abdallah Al-Khatib’s Little Palestine

The First Arab-Israeli War displaced approximately 750,000 Arab Palestinians in 1948. Following the Nakba (catastrophe), many Palestinian refugees began living in Yarmouk, near Damascus, and other locations in Syria. Established in 1957 as an informal camp, Yarmouk grew into a vibrant urban neighbourhood, housing the largest Palestinian refugee population in Syria. Before the Syrian Civil War (which started in 2011 as large-scale protests against the dictatorial regime of Bashar al-Assad and is still an ongoing conflict with many state and non-state actors), it was home to around 150,000 Palestinian refugees who had lived there for decades, integrating into Syrian society while retaining a distinct Palestinian identity.

In fact, in several protest scenes featured in Abdallah al-Khatib’s documentary on life at Yarmouk, Little Palestine: Diary of a Siege (2021), people invoke a unity between Syrians and Palestinians—as large parts of both communities have been subjected to recurring traumas born from authoritarian control and global failures to secure their lives and livelihoods. In the film, screened as a part of the People’s Film Collective’s 7th Frames of Freedom, 2024: All Eyes on Iran/Palestine, an old lady—who was fifteen years old in 1948—remembers the horror of the Nakba and resolves never to leave what eventually becomes the ghetto of Yarmouk, even if it means that she has to die there.

The Siege of Yarmouk was a devastating chapter in the Syrian Civil War. Starting with a blockade of the neighbourhood to cut it off from the city in 2013, it ultimately led to Al-Khatib and his community being driven out by ISIS in 2015. The neighbourhood became a battleground between various factions, including the Syrian government, opposition groups and ISIS. The area was besieged by the Bashar al-Assad regime, leading to severe food, water and medicine shortages. The humanitarian crisis was dire, with widespread starvation and suffering among civilians. When ISIS took control in 2015, conditions worsened. The siege devastated Yarmouk, reducing its population to less than 20,000 and leaving the once-thriving district in ruins.

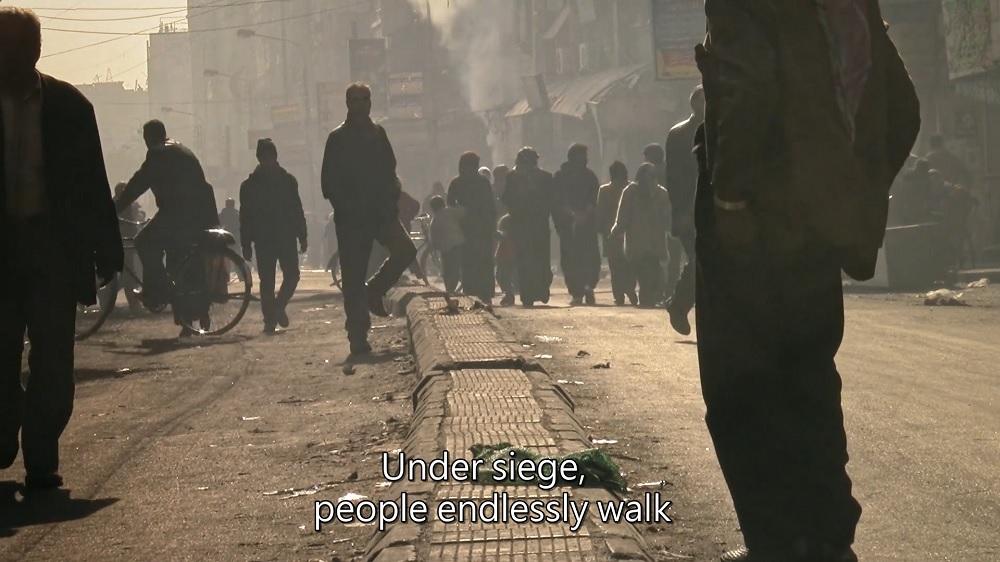

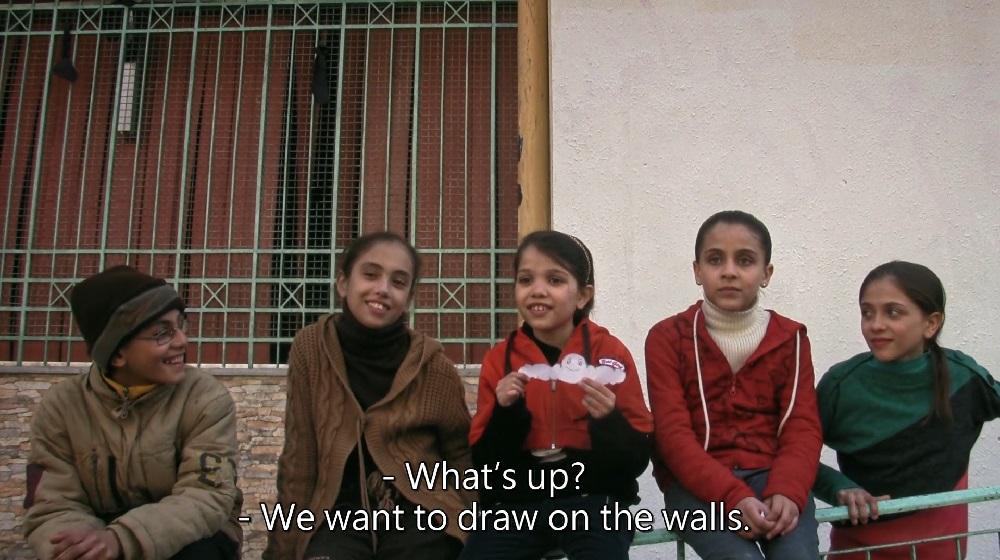

Little Palestine focuses on the perseverance and resilience of the camp’s residents. Al-Khatib, a former sociology student turned filmmaker, lived through the siege and uses his camera to document not only the suffering but also the solidarity, creativity and resistance of the people trapped inside Yarmouk. The film moves beyond mere reportage, offering a deeply personal perspective as Al-Khatib records moments of ordinary life amidst extraordinary horror—children still find ways to play, families gather for meals despite the scarcity and neighbours come together to share what little they have.

For the filmmaker, under conditions of siege, the ‘everyday’ is transmuted into the realm of a lost ideal—so that acts of ordinary living begin to resemble rituals of survival. Checking up on one’s ailing or traumatised neighbours (as Al-Khatib’s mother does) comes to resemble acts of civil activism. The practice of daily journaling, or writing in a diary, similarly, becomes a public ritual of witnessing atrocity and decline. The line between private grief and public mourning dissolves, and the private self begins to distort under the pressure of such conditions—leading to acts of unnatural violence and brutality among the residents of Yarmouk, as Al-Khatib observes despairingly.

The film’s strength lies in its refusal to sensationalise. It avoids graphic depictions of violence, instead allowing the emotional weight of the situation to emerge naturally through the words and expressions of those enduring it. The careful use of sound and the stark, often claustrophobic visuals heighten the atmosphere of entrapment and despair. Al-Khatib’s lens is compassionate, never reducing the camp’s residents to mere victims but instead presenting them as fully realised individuals, who also bear the traumatic weight of their collective history, fighting to maintain their dignity. This can be seen in the conversations Al-Khatib conducts with the children of the neighbourhood, as well as the elderly. The latter reflect critically on their right to exist as free citizens, while the former assert their wish to see a better future for themselves even as they grapple with the meaning of their history. In some scenes, we see Al-Khatib conducting protest marches himself, highlighting the darker motivations of the Syrian government for persecuting them at Yarmouk, while in other instances we hear women asking for the removal of the blockade so that they can resume their work and will not have to rely on charity.

Al-Khatib emphasises certain axioms that pertain to occupied living throughout the film, such as the idea that in Yarmouk, the borders between personal grief and public trauma had disappeared towards the end of the long siege. The film also attempts to establish the condition of exile as intrinsic to modern Palestinian identity. And perhaps not just ‘modern’ too. In a particularly affecting scene depicting protest-chants, the people invoke Jesus Christ’s Palestinian identity and declare him to be a refugee in heaven. As material forms of life become harder to hold on to, conceptual forms and metaphors become ways of appealing to the universality of their experience—so that the indifferent global community can frame Palestinian suffering within a set of recognisable terms.

Isn’t that what feeds the idea of ‘Palestine as Metaphor’—to quote the (English) title of interviews with the famous poet Mahmoud Darwish? He explained, “I think of exile as a metaphor, a continuous metaphor: to be far from your country, to be far from your place.” For him, the exile of Palestinians is part of a larger human narrative of displacement and yearning. Palestine, therefore, becomes a metaphor for the exiled or marginalised individual, as he famously writes: “We are here. We are not here.” This tension between presence and absence is a recurring metaphor in Al-Khatib’s film as well—marked by the voices of Yarmouk’s decade-long residents who were there, and made sure people knew that they were there.

To learn more about Palestinian films, read Najrin Islam’s three-part series on the notion of exile in the work of Razan AlSalah, the exploration of Arabfuturism and reclamation of representation as a form of resistance.

All images are stills from Little Palestine: Diary of a Siege (2021) by Abdallah Al-Khatib, courtesy of the director.