Modernity in Film/Photography: On Chitramahal

Soon after it was first invented in 1837, the daguerreotype process was available for sale in Calcutta markets. The proliferation of colonial photographers tended to largely be concentrated in the metropolises of erstwhile Calcutta, Bombay and Madras. The Bombay Photographic Society was established in the city as early as 1854. Early histories of photography and film in India often focus on these urban centres. What has been relegated to a secondary thought or to footnotes is the development and proliferation of these mediums beyond the colonial city-centres.

C. Yamini Krishna, Sarah Niazi and Rutuja Deshmukh reframe the narrative around the history of photography to highlight the practices prevalent in princely states. In their recently concluded exhibition Chitramahal: Princely Encounters with Photography and Film, exhibited at Harkat Studios, Mumbai, with the support of the Indian Foundation for the Arts, the co-curators present rare photographs, film stills, advertorials and archival footage to turn their gaze to the visual culture from Jaipur, Indore, Kolhapur and Hyderabad. Through their study, Krishna, Niazi and Deshmukh highlight several focus areas in order to make one familiar with the rich history of image-making practices dominant in these princely states. The exhibition considers the socio-political avenues presented by these new mediums, as these nominally sovereign states negotiated with the colonial powers who ruled alongside them.

1.jpg)

Charminar- street view. (Raja Deen Dayal, Hyderabad. NBJ 1416, Raja Deen Dayal Collection. Image courtesy of the IGNCA.)

The exhibition is categorised under several themes, along with visual documents and curatorial notes that provide necessary context. In many ways, the experience of the project is akin to reading an in-depth research paper. There are keywords, captions and broader definitions for each visual document. Armed with an exhibition guidebook, the viewing experience may require an hour (or more) of an alternative history lesson for enthusiasts of visual culture.

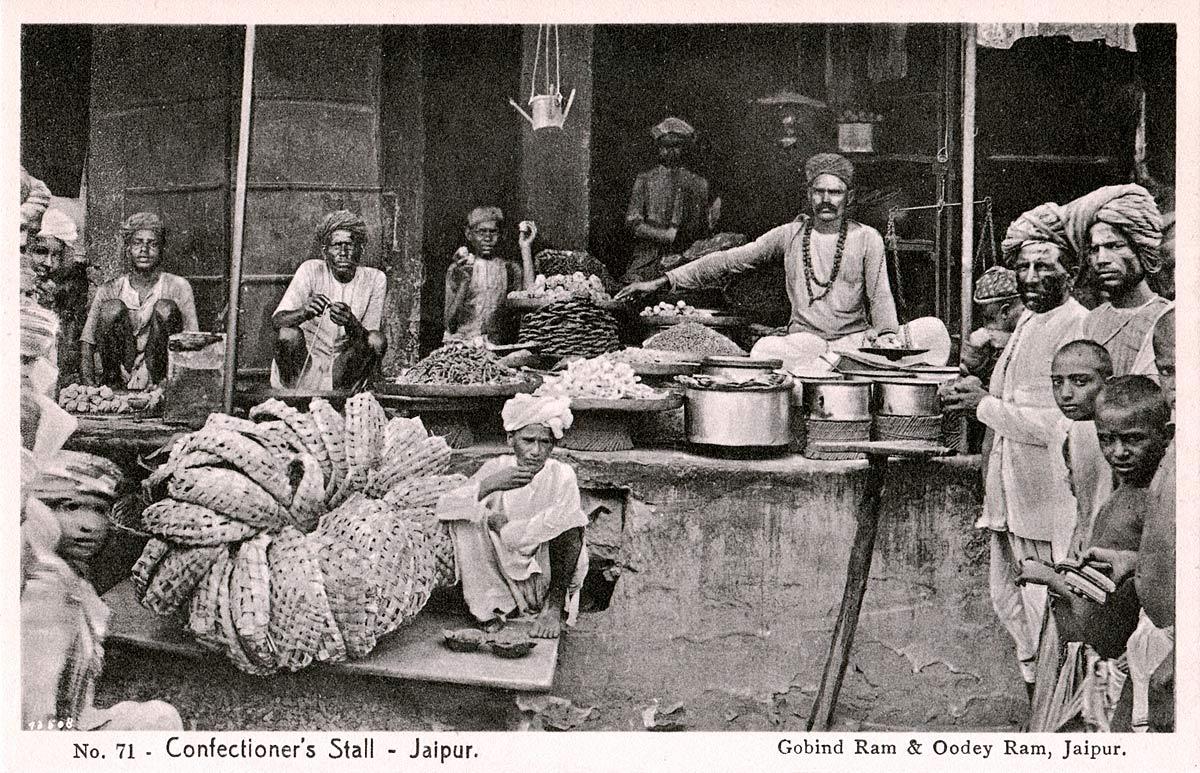

Sourced from several different public and private archives and relying on city historians such as Zafar Ansari—custodians of stories from a lost time—the curators trace a timeline of the genres of photography and film in Jaipur, Indore, Kolhapur and Hyderabad. From royal portraits, photographs commemorating successful royal hunts and images of sports teams with trophies to carefully arranged family photographs, the scope of the photographic ranges from the public to the private spheres of its princely patrons. The display of works sought to question the dominant gaze, highlight experimentations within studio set-ups and unpack the alternative gaze. But perhaps what is most interesting is the conscious attempt to bring to the forefront topics which do not otherwise receive popular attention.

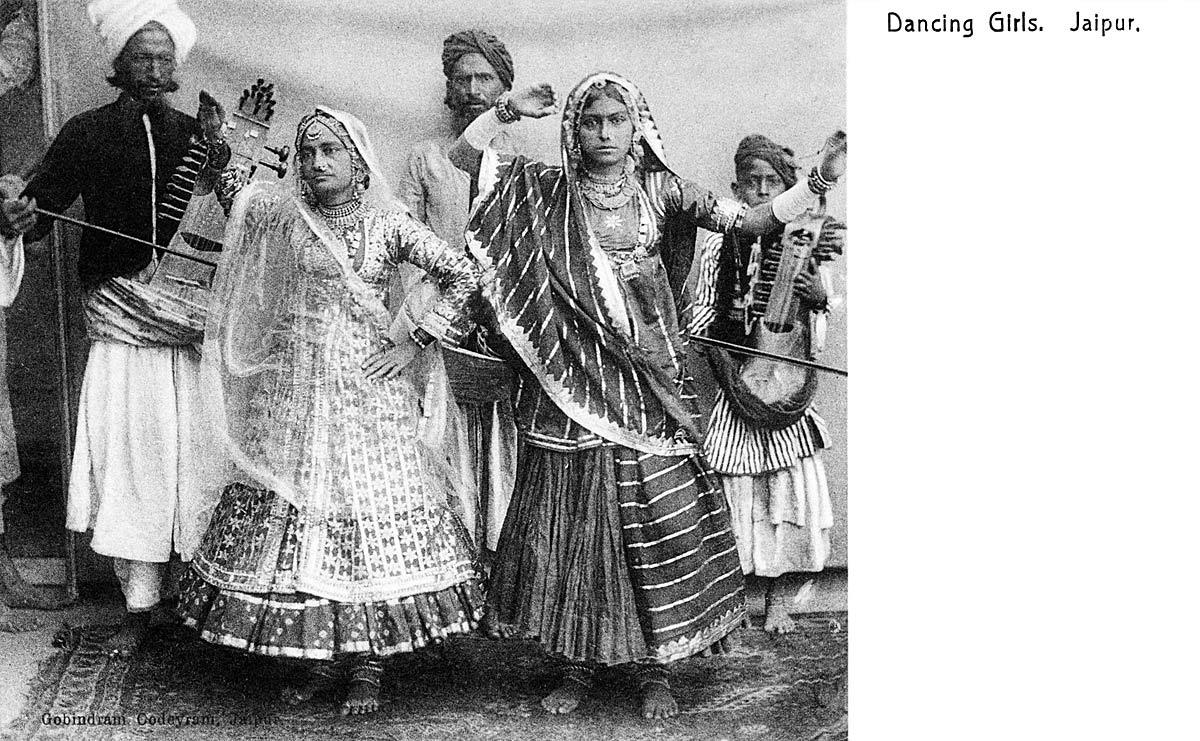

Picture postcard of Dancing Girls. (Gobindram Oodeyram, Jaipur. Image courtesy of Paperjewels.)

With a nod to Raja Deen Dayal, the exhibition allows one to highlight other contemporaries who were making photographs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. For instance, the exhibition features work by Ramachandra Rao and Pratap Rao, state photographers of Indore, who according to a legend had supposedly taught trick photography to Dadasaheb Phalke. The Rao brothers received patronage from the royal family of Indore and were able to set up their own studio that employed many local artists, including the likes of D.D. Deolalikar and M.F. Husain. They popularised the technique of hand painted photographs, touching up the prints in a way that further refined the colours and lines—which came to define their own particular aesthetic style.

Royal patronage also aided in the practice of other professional photographers like Gobindram and Oodeyram of Jaipur and Baburao Krishnarao Mestry ‘Painter’ of Kolhapur. Mestry, who was a self-taught artist and filmmaker, is referred to as the Bahujan founding father of cinema in India. Mestry’s work also contextualises the history of caste politics and resistance movements in the cultural realm. At a time when filmmakers like Dadasaheb Phalke chose to focus on myths for their films, Baburao Mestry was concerned about societal issues. He was the first Indian filmmaker to have cast women in his films (Gulab Bai and Anasuya Bai, in Sairandhri, which was released in 1920). The curators also direct attention towards the perspective of women.

Picture postcard of Confectioner's Stall (Gobindram Oodeyram, Jaipur. Image courtesy of Paperjewels.)

The exhibition presents documentation and several anecdotes as evidence to suggest that women in these princely states were able to dream towards “..radical possibilities of reinvention,” as their curatorial note mentioned. In the princely states, performing women were held in high esteem and were given the liberty to be creative. They were allowed the freedom to be artists and entrepreneurs; the film industry, in turn, granted them opportunities to leave the royal courts and choose to perform for the camera. One such example is that of Mumtaz Begum, who chose to leave the royal court of Indore for a wealthier patron, Abdul Kader Bawla, in Bombay. This ultimately led to the Bawla murder case in 1925, which was made into a film, Kulin Kanta. The patronage offered by princely states also allowed women to work and emerge professionally in photography and cinema.

The other important strand that emerges is the variety of support for the arts with reference to the royal families of the princely states. Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II of Jaipur was an avid photographer, who was always attuned to the innovations within modern photography. He had a tasveerkhana (workshop) built within the royal palace, which functioned as a space where he couldbuild elaborate sets for his staged self-portraits and photographs. Yashwant Rao Holkar II, the Maharaja of Indore, who was captivated by the allure of early cinema and photography, befriended legendary names like Jean Rouch and Man Ray, facilitated connections for the development of cinema in the region, and many-a-times took an active part in performing for the camera himself.

.jpg)

An advertisement of Maharaja Talkies in Indore, which was patronised by the princely elite, listing the theatre's important patrons. (Image courtesy of Media History Digital Archive.)

Chitramahal opens up the world of early photographic histories in India. The exhibition relies on not only formal documentation via archival films and lithographic prints, but also stretches the boundaries of historical research with the presentation of popular culture ephemera, gossip columns, studio cards and advertorials. One is able to gain important insight into movie-going cultures, the diversity of subjects that were captured on camera and the impact it had on stories about India all over the world. Chitramahal enables us to witness the modernity that princely states embodied—both in terms of the technological innovations that were encouraged and the richness of cultural diversity that was promoted. And as the curators rightly point out in their exhibition note, this offers an impressive opportunity to gain newfound perspectives into looking at the aesthetic style that developed as a result within visual culture from the subcontinent.

(L): An installation shot from the exhibition.

(R): A polaroid image of the curators at the photobooth set-up at the exhibition.

To learn more about early photography in India, read Avrati Bhatnagar’s essays on early photography as a fine art in British India, the work of the French explorer Louis Rousselet and James Waterhouse’s documentation of India as part of the colonial project. Also read Ankan Kazi’s two part review of the publication Reverie and Reality: Nineteenth-Century Photographs of India from the Ehrenfeld Collection.

All images are courtesy of C. Yamini Krishna unless mentioned otherwise.