Modes of Self Reflection: On the Genre-Fluid Essay Film

As the lights dimmed inside Bangalore International Centre Hall, the world of essay films came alive. Beyond Story: Encounters with Essay Films, organised over the weekend of 23–25 August 2024, explored the alternate world of essay films. In his opening talk, Avijit Mukul Kishore shared fascinating insights about the format and history of essay films through the lenses of queerness and visual impairment.

Kishore began with a manifesto on the essay film by Mark Cousins, an Irish filmmaker, which tries to define and find it as a genre in and unto itself:

“A fiction film is a bubble. An essay film bursts it.

An essay film takes an idea for a walk.

Essay films are visual thinking.

Essay films reverse film production: the images come first, the script, last.

Commentary is to the essay film, what dance is to the musical.”

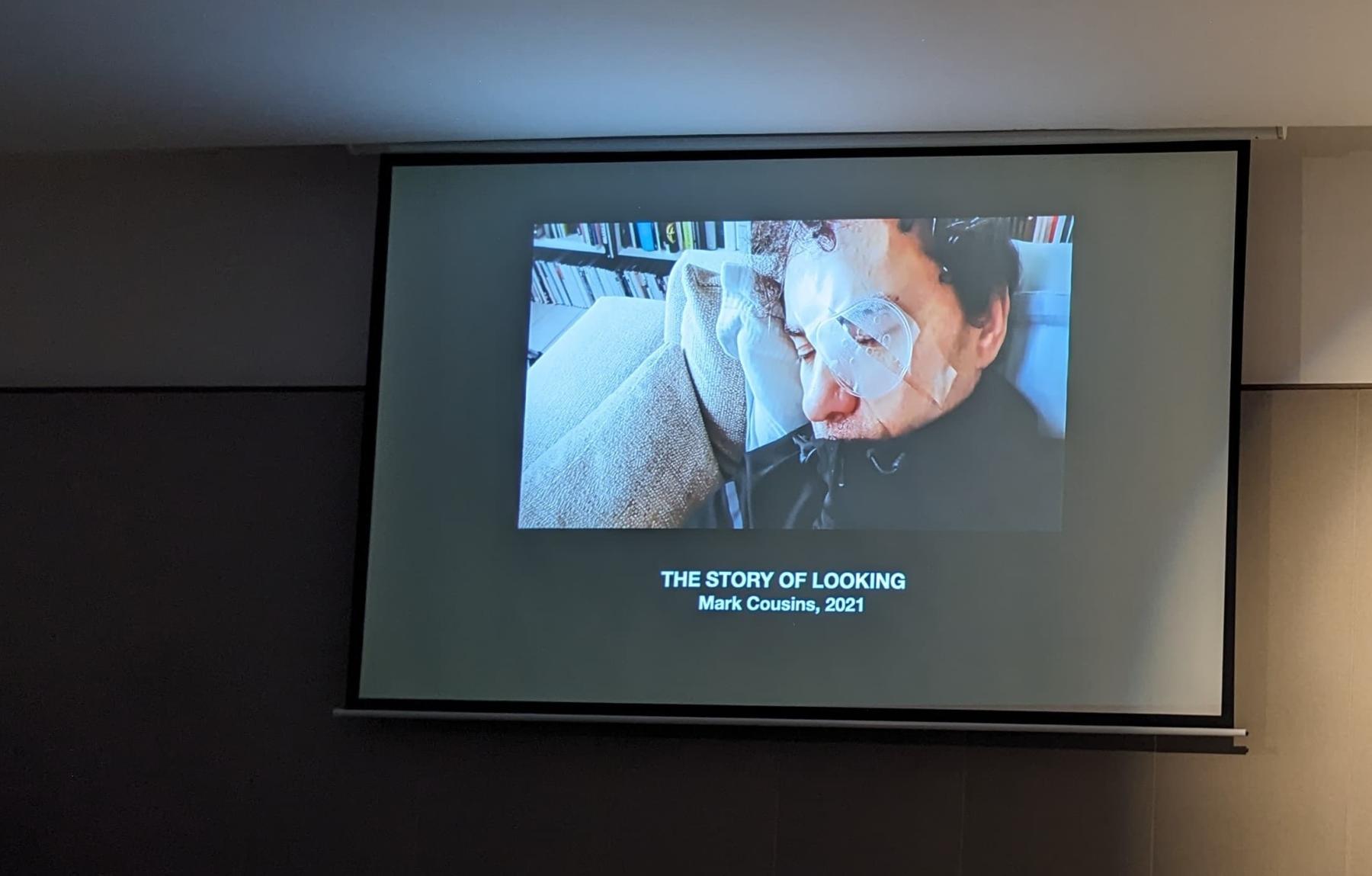

A still from The Story of Looking (2021) by Mark Cousins.

While Cousins outlines the nuances of making an essay film, Kishore also considers the idea of essay films being genre fluid as they traverse multiple narratives, themes and styles. The articulation of the personal and lived experiences of filmmakers is perhaps the thread that connects these films as a genre.

Cousins’ autobiographical film The Story of Looking (2021) traces the filmmaker's journey with a cataract, poignantly deliberating on the fine line between seeing and vision, and what it means to make films when your eyes fail you. We see almost “selfie-esque” shots of the filmmaker in bed contemplating whether to step out and experience the world or shut his eyes and imagine it. He turns the camera on himself—as if to say that even if he cannot see, he can still be seen. The film is filled with blurry and distorted images, symbolic of the filmmaker's battle with losing sight. The prospect of his eyes being cut into during surgery forces him to remember all that he has seen through his life. He enunciates, “Looking has been my joy, but that world must be closing.”

A still from Derek Jarman's Blue (1993).

Similarly nostalgic about the lost world of seeing, writer, filmmaker and gay rights activist Derek Jarman contemplates whether losing half his sight would halve his vision as well. Made nearly 30 years earlier, the video essay Blue (1993) is an expression of losing sight and coming to terms with visual impairment. When Jarman lost his vision after being diagnosed with HIV, his world was rendered blue, and it is this imagery that the filmmaker portrays, creating a film where the only visual is blue. And yet, the onus of meaning-making shifts from being squarely on the shoulders of the filmmaker. “The audience will tell me what I have made,” Jarman claims.

A still from Derek Jarman's The Garden (1990).

In snippets from another film, The Garden (1990)—a spoof of a Broadway number, Jarman uses Super8 footage, green screens, colour filters and many other effects to express his anger and frustration at the persecution of gay men in 1980s London. We see a gay couple dressed in pink suits carrying a baby as old stock footage of pride marches plays out in the background. The film not only creatively makes meaning through shot live action and archival found footage, but it is also a document of Jarman’s reflections on life, illness, love and being queer.

A still from Rohan Shivkumar's Lovely Villa: Architecture as Autobiography (2019).

Moving from the personal, Kishore looks at S.N.S. Sastry’s Keep Going (Lage Raho, 1971), commissioned by the Indian government during the 1971 Bangladesh war. Building on a narrative using archival footage of Sastry’s own films produced by Films Division, Kishore sees Sastry’s process as a journey of self-reflection through self-referencing. Carrying this thread further is Rohan Shivkumar’s Lovely Villa: Architecture as Autobiography (2019), which also interweaves multiple formats like photographs, voiceovers, home music recordings and home video footage, but is more personal in its approach. Shivkumar reflects on his home, Lovely Villa, where he grew up in the 1970s, and which was designed by the noted architect Charles Correa.

A still from Keep Going (Lage Raho, 1971) by SNS Sastry.

While both films reflect on the larger idea of the government, the middle class and our relationship with paternal figures, Shivkumar places his personal story against the backdrop of how citizenship was imagined in the 1970s through architecture and housing colonies. The film is a visual essay on how the architecture of a space creates stories and how stories in turn shape spaces. Moreover, while Shivkumar uses commentary strongly to guide the visuals that unfold, in Sastry's film, it is the visuals that guide the narrative, almost as if shots become notes, and the film becomes an essay culled out of these notes.

A still from Keep Going (Lage Raho, 1971) by SNS Sastry.

Through a sensitive curation of a diverse set of films, Kishore discusses how the essay film draws from the personal and autobiographical, quite often spilling onto the audience who are privy to a personal lens. Filmmakers use the camera almost like a diary, presenting visual entries of raw, meaningful moments. At its core, then, the essay film reveals a form of self-reflection on the part of the filmmaker, without the burden of entertaining audiences or having to adhere to the rules and norms that conventional filmmaking demands.

To learn more about Avijit Mukul Kishore’s work, read Arushi Vats’ essay on Lovely Villa: Architecture as Autobiography (2019) and Nostalgia for the Future (2017) as well as Ankan Kazi’s reflections on Squeeze Lime in Your Eye (2018).

All images courtesy of the author.