The Clarity of Delirium: Avijit Mukul Kishore’s Squeeze Lime in Your Eye

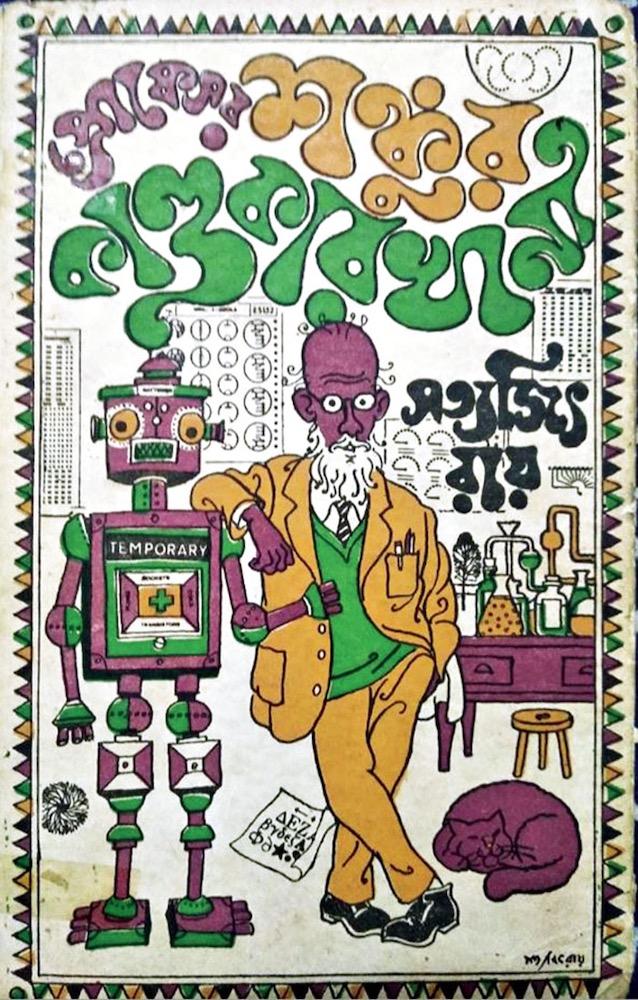

Professor Shonku was a literary creation of Satyajit Ray, appearing in stories from 1965 onwards. His expertise across several scientific disciplines was translated into an ascetic vision of (non)participation in the world scientific community. (Front Cover of Professor Shonkur Kandokarkhana. Kolkata, 1970. Image courtesy of Ananda Publishers.)

One of the most enduring literary characters created by Satyajit Ray was the eccentric inventor and scientist, Professor Shonku. He lived somewhat off the map of the normative, international scientific world of the Cold War era because his objectives were markedly different from global norms of scientific research. The kind of objectives Ray adopted for Shonku were largely aligned with the politics of science in postcolonial India—reflecting a critique of the Western norms of science as just another means of commodity production in a late-industrial age. Shonku, in fact, made several “alternative” objects that could be seen as the products of Indian liberal fantasy, like the “Miracurall”—a tablet that could cure any ailment. These objects were not only touched with the imagination of utopic thinking, but were marked by the maker’s authority and his unwillingness to commodify or industrialise the production of any of them. There was a belief, in other words, that the moral prerogative of doing science “correctly” could begin outside of those Western norms—in the safety of Shonku’s laboratory in the boondocks—so that the unruly line of progress could be disciplined into a straight line and history’s proper ends could be brought into focus once again. Ray’s ideology was certainly influenced by Nehruvian postcolonial politics, but it was also nurtured by the reform-minded elites of the Brahmo Samaj. This introduced a more puritanical zeal into the mode of liberal progress and had been adopted by the Ray family a few generations before the filmmaker’s birth.

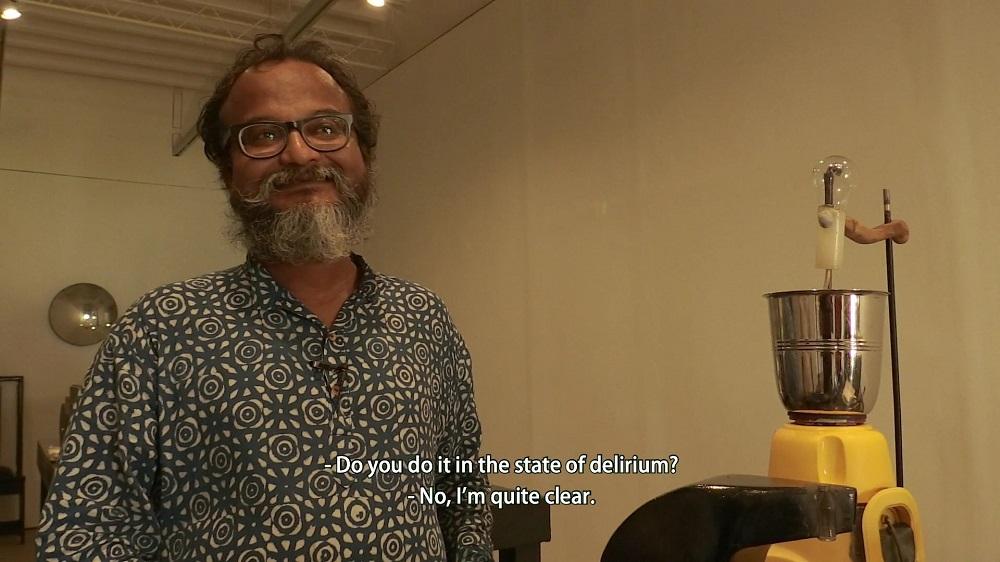

Kausik Mukhopadhyay makes installations out of used electronic items and equipment, usually twisting them out of their humble utilitarian origins to suggest more unorthodox possibilities of structure and fantasy. (Still from Squeeze Lime in Your Eye. Avijit Mukul Kishore. 2018. Image courtesy of the filmmaker and Public Service Broadcasting Trust.)

Kausik Mukhopadhyay, the subject of Avijit Mukul Kishore’s documentary Squeeze Lime in Your Eye, was also raised in a Brahmo environment. However, Mukhopadhyay says that he moved away from it soon enough—considering it to be little more than an upper caste Hindu project (of improvement). As a result of this, he comes across as a sort of counter-Shonku figure. He seems to be invested in the performance of outsiderness and eccentricity, but is also equally committed to introducing notes of apocalyptic thinking, breakdown, obsolescence, melancholy and unfulfillment in the lives of the objects that he “invents” through finding, reworking and reappropriating. As a “mad scientist” of post-liberalisation India—when consumerist objects from electronic goods to expensive toy sets exploded onto the market—he works in a laboratory that specialises in dramatically silly inventions that can upstage the intentional narratives of objects, scientific research and modernity.

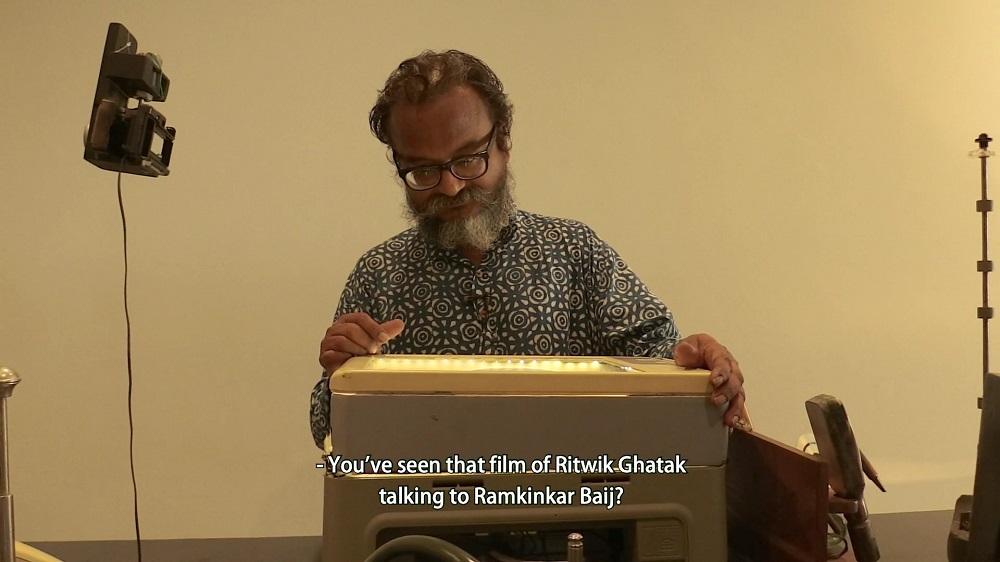

Mukhopadhyay spent his formative years at Santiniketan, absorbing the culture of the small university town and its openness to the rural life around it. Major mid-century modernists like Ramkinkar Baij and Nandalal Bose had also worked and taught there earlier. (Still from Squeeze Lime in Your Eye. Avijit Mukul Kishore. 2018. Image courtesy of the filmmaker and Public Service Broadcasting Trust.)

Squeeze Lime in Your Eye excels in bringing these aspects to the fore. In the garb of a conspectus on Mukhopadhyay’s life and work, it constantly jettisons—with the collusion of the artist—any attempt to collapse his works into a simple biographical narrative of growth or “development.” This is not to suggest that biography does not seep into his work as well, as can be seen with his sculpture Mother’s Home, where the memory of his mother’s practice of obsessive collection is transformed into a mechanical ode of staccato sounds and skeletal gridwork suspended in space. Elements from his past—from his Santiniketan years to his subsequent move into Baroda University and later Mumbai’s Kamla Raheja Vidyanidhi Institute of Architecture and Environmental Studies, where he taught architectural thinking of a certain experimental variety—are employed to pin down certain parts of his practice by giving them institutional meanings. However, the film also suggests that the playful instincts of Mukhopadhyay might invite a similar approach to reading his practice too: as a series of provocations with no neat lessons to draw from and an inventory of lost objects in search of new homes of significance or inspiration.

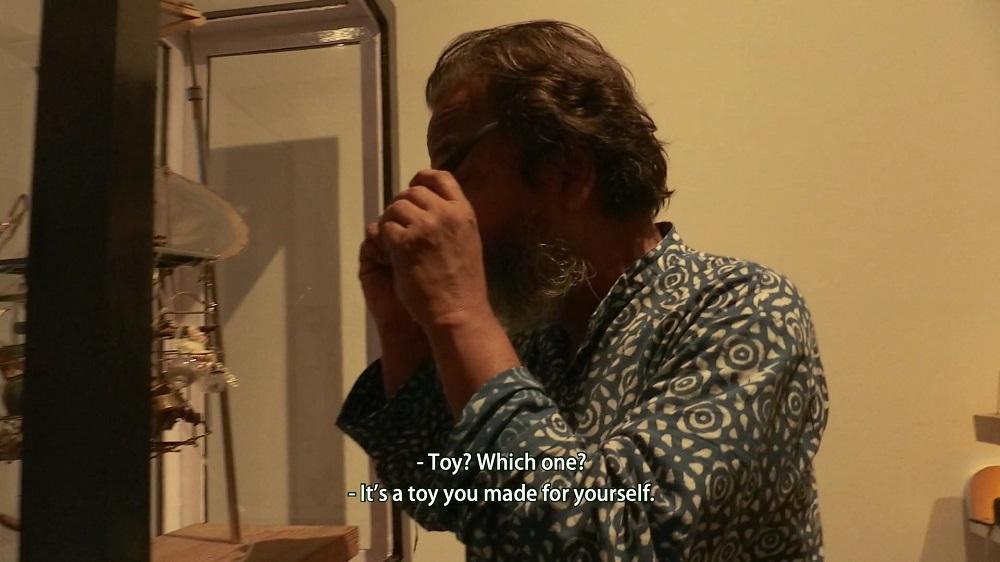

Mukhopadhyay’s work rejects the industrial finish offered by contemporary mass-produced objects, preferring instead to keep their borders of form or functionality open to change and spontaneous associations with other, surrounding objects. (Still from Squeeze Lime in Your Eye. Avijit Mukul Kishore. 2018. Image courtesy of the filmmaker and Public Service Broadcasting Trust.)

It is not enough to simply infuse the mechanical world of technology with disordering fantasies—this much was already established and repeated by the time of the Dadaists or the Fluxus artists of post-war Europe and North America. In Mukhopadhyay’s restless, nervous energy, one can see an additional distaste for the formal aesthetic of industrial production (whereas someone like Duchamp was more likely to fetishise the perfection of the industrial, readymade finish). His objects are wired differently, finished indifferently (although attentively towards creating the effect that he desires) and made to enter into a cloud of associations and contexts drawn from political history, cinema and technological discourse. He also gives them an almost erotic animism that suggests an organic life force, hidden from the realms of ordinary science. Rendering objects into “toy-hood,” a more unstable category is proposed for the new inventions as a site where the ludic, childlike desire for play and destruction create a tense relationship with intellectual thought. These objects do not always suggest fully formed thoughts, but they provide one with materials and trajectories for new ideas and new ways of refitting the old world. The tone of his satire would seem to mock our expectation of “solutions” from contemporary scientific discourse. Here, one witnesses a more melancholic—and oddly sensual—biography of modern man unfolding through the afterlife of his repurposed objects, responding more appropriately to what the Russian socialist Alexander Herzen once said, that “…in general, modern man has no solutions.”

Mukhopadhyay’s inventions push the envelope of utility towards absurdism. This “sheep counter” is meant to solve the problem of insomnia, foregrounding the hubristic claims of modern inventions that seek to provide perfect solutions for deeply traumatic—but natural—responses to our time of anxiety and global meltdown. (Still from Squeeze Lime in Your Eye. Avijit Mukul Kishore. 2018. Image courtesy of the filmmaker and Public Service Broadcasting Trust.)

Kishore’s film (made with the participation of Rohan Shivkumar) finds parallels with other iconic figures, like Ritwik Ghatak. Their conversations reference Ghatak’s unfinished documentary on Ramkinkar Baij (another Santiniketan artist) as well as his film Ajantrik (The Mechanical Man, 1958), whose protagonist shares a similarly complex personal relationship with his mechanical companion—an old 1920 Chevrolet jalopy named “Jagaddal.” Kishore’s filmography is built around exploring a condition of documentary film that arrives after the tortured production histories of the Films Division (FD) era. Nostalgic as well as critical about the claims of those educational, information-driven state-sponsored narratives, his documentary on Mukhopadhyay—funded by the Public Service Broadcasting Trust (PSBT)—finds an ideal subject with which to continue his explorations into this form of the post-FD documentary. While Mukhopadhyay’s work rejects the certainties of earlier scientific truisms of postcolonial India (and global modernity), Kishore’s film gently satirises the older narratives of sentimental realism, which were employed in FD films on development and industrialisation. While showing a particularly comic invention—a mechanical clock for counting sheep as cure for insomnia—he overlays it with FD-style state-of-India montages with their jingle-like jazz background scores. It produces a sense of cheerful harmony even as the subject deals with disjunctions, breakages and disharmonies.

Kishore’s film parallels the encounter between Mukhopadhyay and himself to that of Baij and Ghatak. The earlier film remained unfinished, as if following one of Mukhopadhyay’s own principles of aesthetic production. (Still from Squeeze Lime in Your Eye. Avijit Mukul Kishore. 2018. Image courtesy of the filmmaker and Public Service Broadcasting Trust.)

Rendering objects unto toy-hood, their use value is transformed and manipulated in Mukhopadhyay’s work much as children use toys to mould their personal fantasies of possession and transformation. This involves the play of destructive and creative instincts, producing crossings between purpose, memory and form. (Still from Squeeze Lime in Your Eye. Avijit Mukul Kishore. 2018. Image courtesy of the filmmaker and Public Service Broadcasting Trust.)

Instead of a neat political opposition to these older visions of progress, Mukhopadhyay’s work seeks to throw an anarchic spanner in the reception of the modern world of technology. This intervention is not to stop the machines or destroy them, but to transform their raison d’être in the modern industrial landscape—by making them run backwards or sideways, teaching them to dream and maybe live a little life outside, even if that space outside is the white cube of the contemporary art gallery.

To read more about Kausik Mukhopadhyay’s work, please click here.