Modelling an Image: Photographing the Bengali Actress

In her essay “Capturing Stars: Bengali Actresses Through the Camera of Nemai Ghosh,” Sabeena Gadihoke presents a range of contexts that influenced the images of women taken by photographers like Ghosh and filmmakers like Satyajit Ray. A capacious archive of these images fills the volume of Delhi Art Gallery’s tribute to the photographer who created an informed path for the casual viewer to gain access into the sets and formal processes that surrounded Ray’s filmmaking.

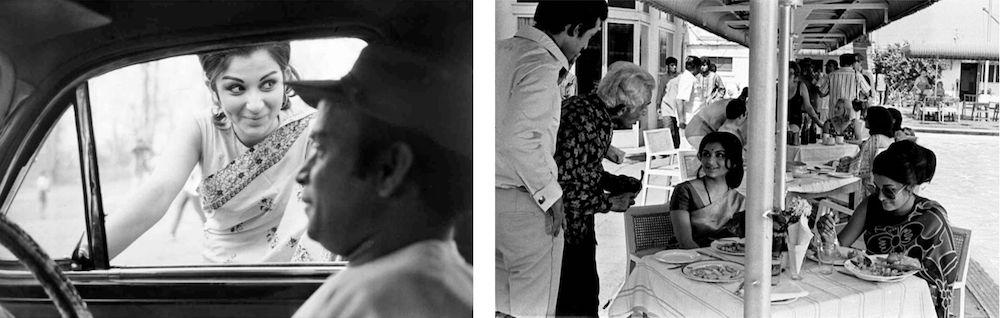

Scenes from Aranyer Din Ratri (Days and Nights in the Forest, 1969) and Seemabaddha (Company Limited, 1971) on the left and right respectively. Sharmila Tagore was a popular subject for Nemai Ghosh’s lens. She met him for the first time in Palamau, Bihar, where Ray was shooting Aranyer Din Ratri. As Gadihoke writes, “After seeing some of his photographs, Tagore decided to hijack Ghosh on a rest day for the unit.” Eventually, she was so impressed with his photographs and impromptu photo sessions that she gifted him with a lens.

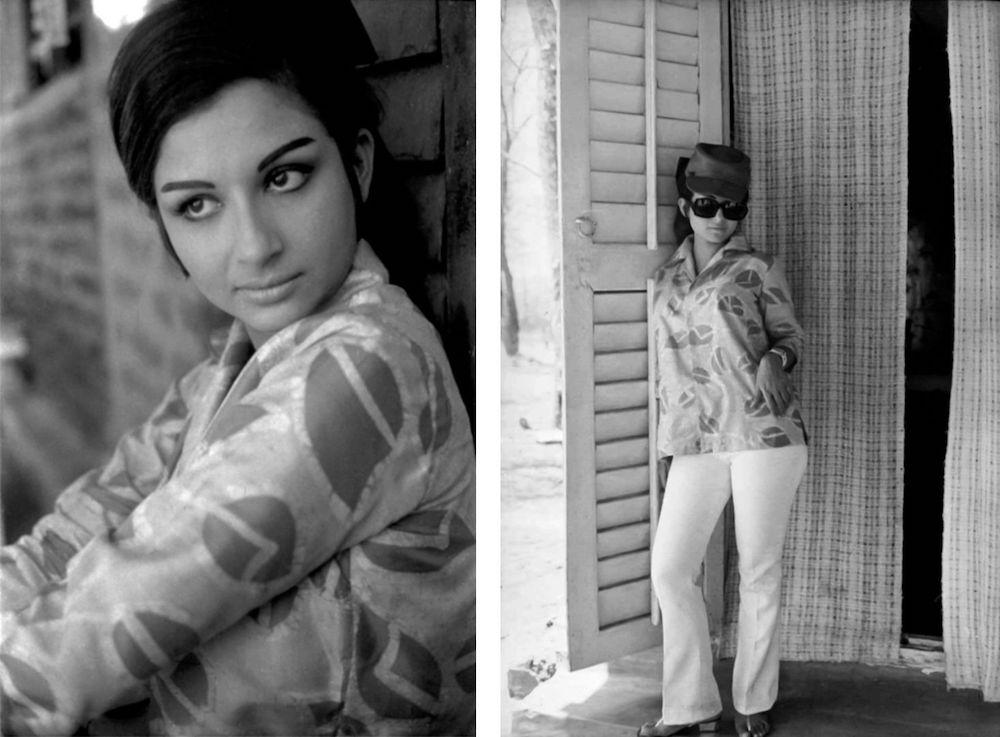

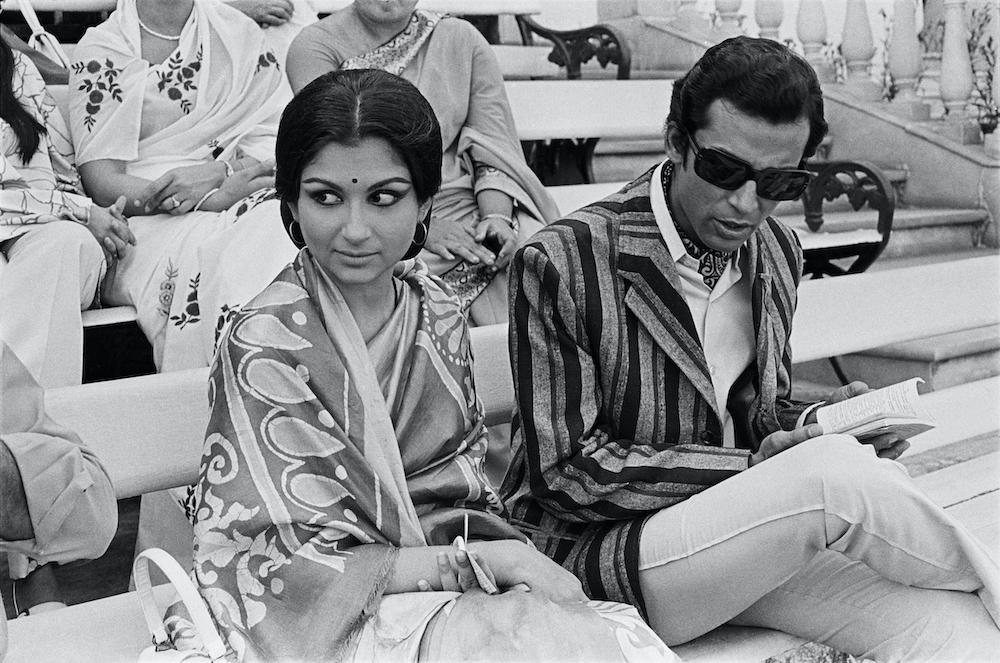

Gadihoke explores the changing images of Bengali actresses through the representations of Sharmila Tagore, Supriya Chaudhuri, Suchitra Sen, Jaya Bhaduri and Aparna Sen, as well as a whole host of “non-Bengali” actresses who also played important roles in Ray’s Bengali and Hindi-language films, like Smita Patil, Simi Garewal and Suhasini Mulay (who assisted him on the shoot for Jana Aranya, The Middleman, 1975). Ghosh usually followed the template of Ray’s idealistic depiction of women, but often also took in other waves of influence—from contemporary magazine photography, textile advertisements, pin-up images and cinemas from around the world—that the filmmaker was careful to exclude (or at least present with a supplement of narrative explanation) from his own images. Since Ghosh’s photographs were meant to act as ciphers into the world of the film or that of the actress as an assemblage of institutional, personal and commercial instincts; many of his photographs are imbued with the playful character of actors like Sharmila Tagore or Jaya Bhaduri. Tagore, especially, liked to play around with her own image, polemically split between the art house roles of Ray's films and as a commercially successful heroine in Bombay Cinema. This accounted for a proliferation of her images in the public sphere through advertisements and magazines like Filmfare or, later on for other Bengali actresses, Anandalok.

The image on the right was taken on the sets of Aranyer Din Ratri, showcasing another moment that was staged spontaneously by Tagore for Ghosh’s camera—almost as a moment of temporary, playful relief from the frames that were composed by Ray. Gadihoke writes, “…we recognise these stances to be similar to popular pin-ups or other glamorous photographs even as we draw upon other kinds of circulating knowledge about the career and off screen life of stars like Tagore.”

Her shifting persona reflected, Gadihoke argues, an anxiety in the vision of male artists like Ghosh or Ray. Characters played by actors like Tagore or Aparna Sen (especially in her cameo for Aranyer Din Ratri, Days and Nights in the Forest, 1969), frequently embodied the attraction of an ideal—whether spiritual (like in Devi, The Goddess, 1960) or materialistic:

“Set against the dystopic backdrop of economic crisis when disillusionment with a Nehruvian vision of socialism went hand in hand with an increasing fascination for consumer goods, Pratidwandi (The Adversary, 1970) and Jana Aranya (The Middleman, 1976) reflect the anxieties of the unemployed middle-class young man that often coalesced around women’s encounters with more visible forms of consumption, especially their appearance.”

The perception of these characters involves—on the audience’s part—an effort to fill in these abstractions with the teasing details of the actor’s lives under the limelight. This could partially explain the easy relationship between these images—many of which were taken by Ghosh with a lens bought for him by Tagore herself—and the public persona of these actresses.

Sharmila Tagore and Barun Chanda in a scene from Seemabaddha. This was the second film in Ray’s Calcutta trilogy, exploring the urban malaise of the time.

The predominant tendency of this aesthetic leaves little room for these actresses to assert any control over their own images. Could this explain why a star actress like Aparna Sen—when she started making her own films—frequently used male photographers as shadow protagonists to her main female actors? In Parama (The Ultimate Woman, 1984), the title character—played by Rakhee Gulzar—finds herself transformed by the bold, rejuvenating erotic shock of the photographer Rahul (played by Mukul Sharma, who was married to Sen at one point). Rahul wants to take her photographs for a suitably contrite male modernist project titled “An Indian Housewife.” Even as her image of herself unlocks a newfound taste for a more passionate existence outside the role of a “housewife,” the path is strewn with terrors as the photographer violates her trust and publishes a rash of erotic photographs of her without her consent. In Mr and Mrs Iyer (2002), the photographer is played by Rahul Bose, who is a Muslim man travelling through a riot-inflected landscape with his co-passenger, Meenakshi Iyer (played by Konkona Sen Sharma, who is Sen’s daughter) and her screaming infant. As an upper-caste, Brahmin, married woman Mrs Iyer’s social role allows her to find that position of power in the norm which, in turn, gives her the ability to extend her protection to Bose’s character from a marauding Hindu nationalist mob. The fiction of their marriage is a cautious inversion of the fiction of Parama and Rahul’s “extra-marital” relationship.

Aparna Sen started her career as an actor in Ray’s films. She would eventually go on to make films of her own like Parama (The Ultimate Woman, 1985) and Mr and Mrs Iyer—where male photographers and the politics of photography were put under scrutiny.

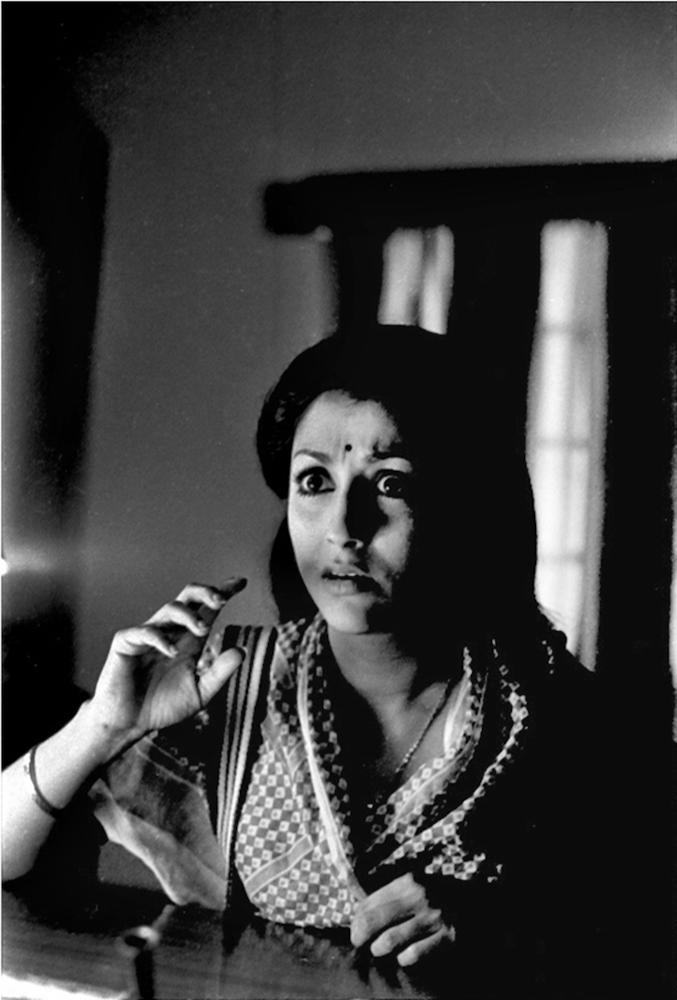

Smita Patil, from a scene in Sadgati (The Deliverance, 1981). She straddled the world of “parallel”/ art house cinema as well popular, mainstream cinema; working with filmmakers like Shyam Benegal, Ketan Mehta, Govind Nihalani and, as in this case, Satyajit Ray. As an activist and member of the Women’s Centre in Mumbai, she deliberately lent her image to represent a wide variety of women on screen—especially those from rural and traditional backgrounds—exploring the changes in their lives over time.

These fictions of self-transformation, after all, require as much participation by the male artists as the female actors. And an inverse relationship could easily show up the necessary performances required by the subjects of such images. Instead of adopting the almost puritanical ethic of objectivity often employed by Ray, Sen’s images are informed by an attempt to work through the dense networks of power and influence—which could include gossip and rumours circulating about their personal and public lives—that informed the choices of actresses in Bengali cinema.

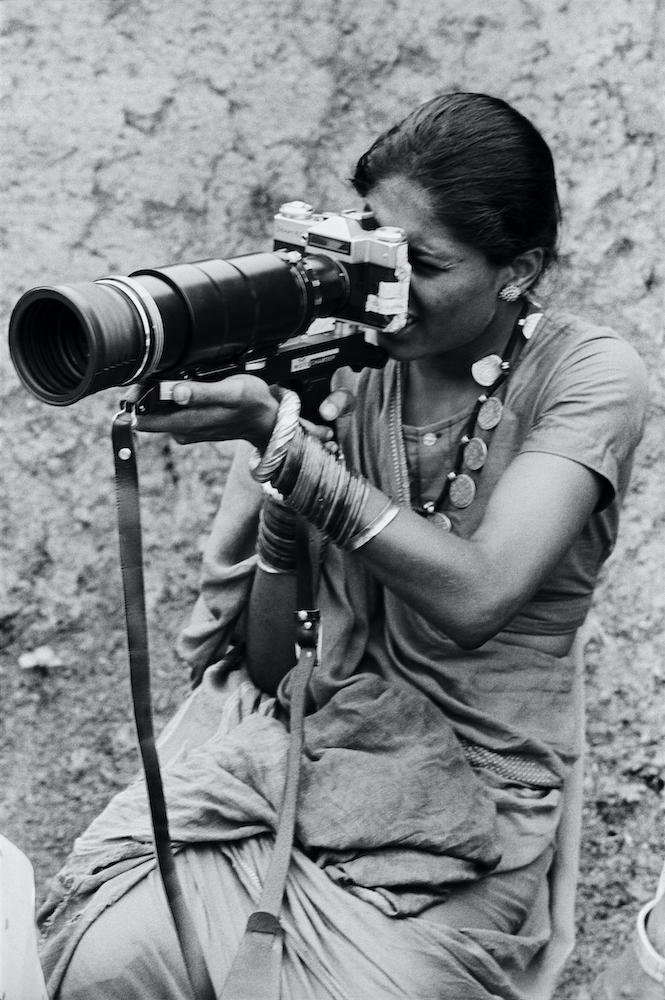

Taken between shots on the sets of Sadgati, Smita Patil wields a camera with a large telephoto lens.

To read more about stardom in India and the representation of women, please click here and here.

All images by Nemai Ghosh. Images courtesy of the Delhi Art Gallery.