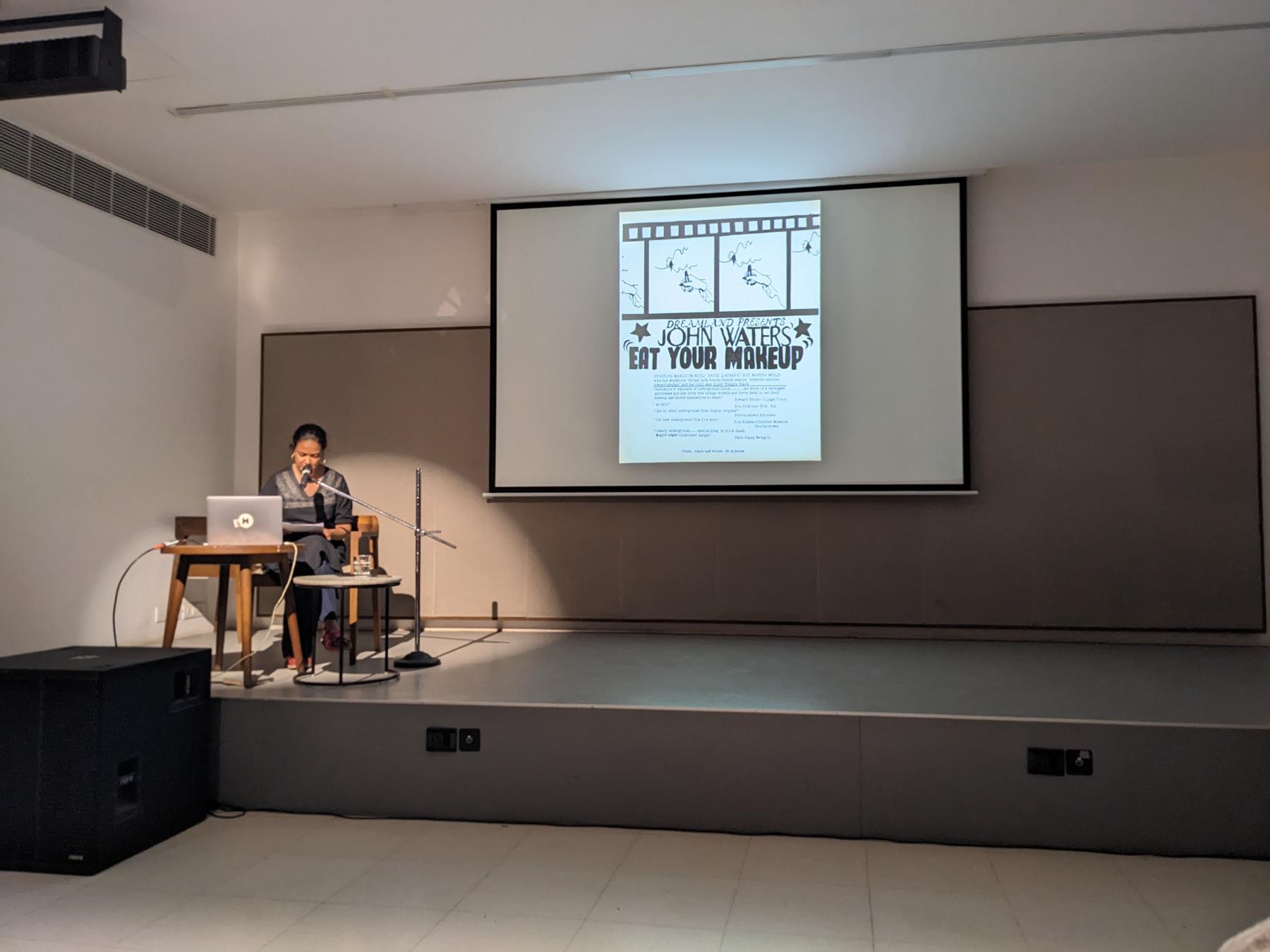

Eat Your Mother and Father: A Talk by Yashaswini Raghunandan

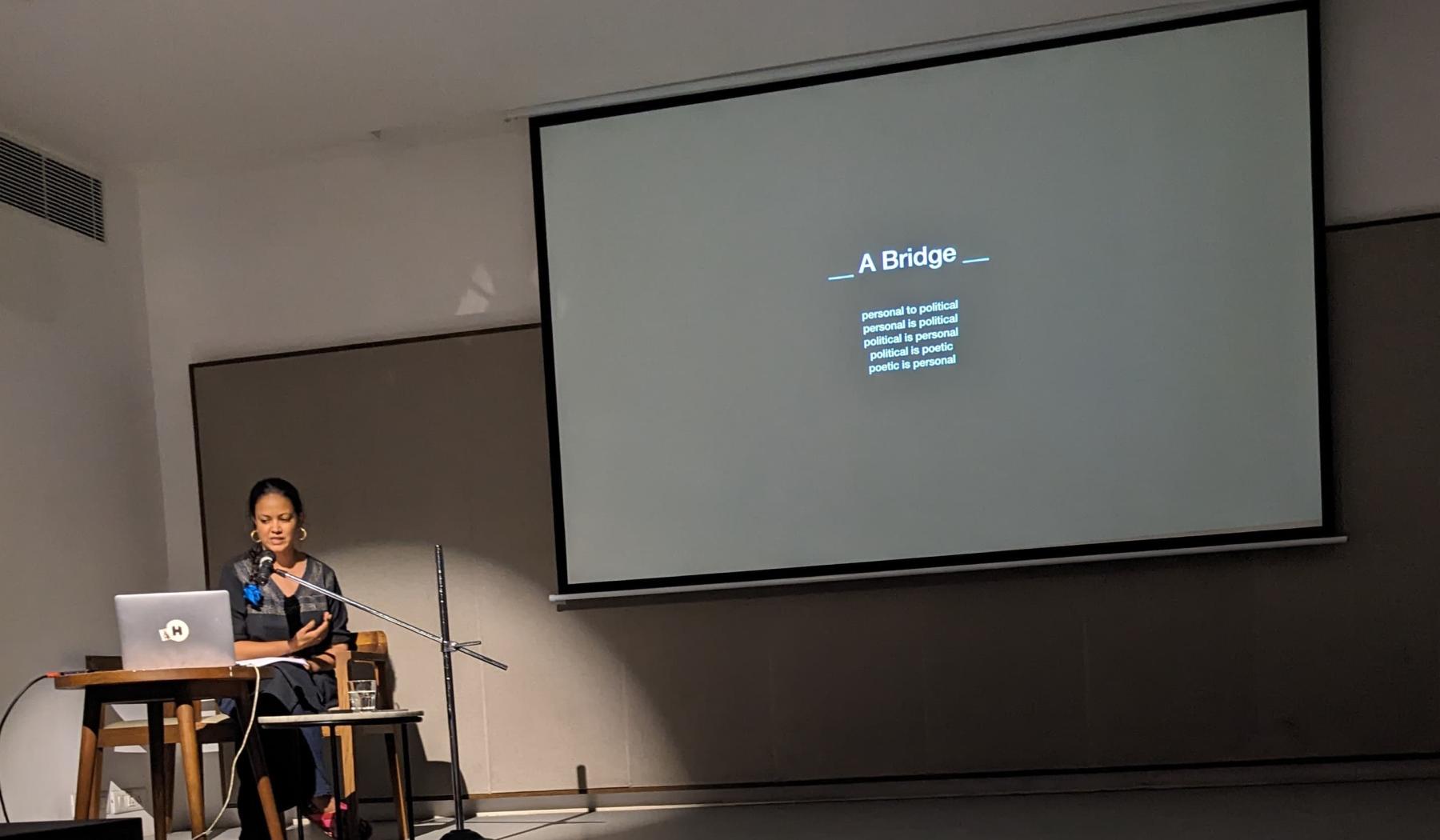

Presented as part of Beyond Story: Encounters with Essay Films at the Bangalore International Centre, Bengaluru-based filmmaker Yashaswini Raghunandan’s talk “Eat Your Mother and Father”—the title inspired by John Waters’ film Eat Your Makeup (1966)—discussed the interactions between personal and essay films. Characterised by its autobiographical nature, where filmmakers turn the camera towards themselves, their families and their immediate surroundings, Raghunandan describes personal filmmaking, particularly first-person documentaries, as films that have the potential to “offer a unique lens through which filmmakers explore their own lives, relationships, and identities.” While films from this genre are sometimes perceived as being “self-absorbed, ego-driven or myopic,” these films also allow for audiences to “engage with personal stories that resonate larger universal themes.”

Yashaswini Raghunandan shares notes on Personal Films.

Raghunandan first introduced two films by queer Asian filmmakers, Will You Look at Me (2022) by Shuli Huang and Snapshots from a Family Album (2003) by Avijit Mukul Kishore. In both films, the filmmakers let viewers into their homes as they use the camera to begin conversations with their mothers.

.jpeg)

A still from Snapshots from a Family Album (2003) by Avijit Mukul Kishore.

In Snapshots from a Family Album, an extreme close-up of Kishore’s mother portrays her proximity to the camera and to the person holding the camera. A mundane yet playful conversation between mother and son plays out as they watch television in bed. She is acting and performing for him and the camera. Once she is done with her act, she asks him to stop filming and covers her face, expressing her irritation.

We are rarely let into such a personal and private space in the non-fiction, documentary world of filmmaking. Consent and ethical filming of subjects prevents the camera from being this close to the subject it is filming, not only physically but emotionally. In Kishore’s film, the camera is present, seen and not hidden as it mostly always is.

In Will You Look at Me, the filmmaker returns to his hometown in China, after having lived in America for a few years, to have “a long-due conversation with his mother, in a quest for acceptance and love.” Huang, unlike Kishore, seems to share a far more troubled relationship with his mother. The film is an attempt to confront his mother and steer her into speaking about topics that have been avoided for years.

A still from Will You Look at Me (2022) by Shuli Huang.

Huang and his mother can be heard crying while having difficult conversations. In such scenes, neither of them is seen. They are only heard, as if they are in a room adjacent to the viewers. We see an old image of his mother holding him as a baby, looking straight into the camera. This juxtaposition between the sound of where they are today and the image of where they used to be, helps us empathise with what the filmmaker has lost and what he may be trying to find.

If Huang’s film is cathartic and documents the difficult relationship that he shares with his mother, Kishore’s film reminds us of the tenderness that draws him to his mother. In letting us into their homes, the filmmakers urge us to reflect on our own homes and private lives. Thus, it is not only the film that is personal, but the process and act of filming itself that become personal.

This approach allows for a raw and authentic exploration of personal histories and emotions. The genre blurs the lines between documentary and narrative, often incorporating elements of both to create a hybrid form that is both introspective and engaging.

2.jpeg)

A still from A Picture of you (2012) by Ajay Noronha.

If personal films can be a medium to explore emotion, they can also help reconstruct memory. Ajay Noronha’s A Picture of You (2012) is a cinematic effort to piece together an image of his father, who passed away when he was six years old. A photograph of his father and a few scattered stories are all the memories left of his father. Through conversations with his mother and other relatives, he tries to build a memory of a father he never knew.

The story of the night his father died plays out as audio recordings of conversations with his mother and other relatives, with images of his father from family albums running on loop. There is a sense that this is a story that has been repeated so many times that the telling of it no longer holds in it grief and sorrow. It is an event, an incident being recounted for a son, whose six-year-old self, while present as these events unfolded, was unaware of what they meant and whose scattered memories begin to make sense as these narratives unfold.

.jpeg)

A still from Picture of you (2012) by Ajay Noronha.

Noronha, too, holds the camera close to his mother as she moves around the house, dusting objects. Even as Noronha probes and pushes his mother to divulge something about his father, she is unable to understand why he is interested in knowing about a man he grew up without. Again, like in Kishore’s film, we see her questioning his cinematic choices, not seeing the documentation of the routines around the home as an attempt to draw larger meanings from personal contexts.

.jpeg)

A still from Picture of you (2012) by Ajay Noronha.

As filmmakers get up close and personal with their subjects in personal films, the idea of consent becomes complicated. They continue to film despite consent being withdrawn, in the self-knowledge that they would not include anything in the film that would implicate their family or themselves. The unlimited access to film allows for the camera to become a part of the living room, the home, with characters responding to it, playing with it and even being handed the camera to film the filmmaker.

These films are like cinematic home videos, honest revelations of intimate secrets that come together to uncover certain universal truths. The filmmakers reveal their lives for collective introspection, to understand not only themselves but to explore the imagination of oneself as a social, cultural and political being.

Yashaswini Raghunandan shares notes on Personal Films.

To learn more about Beyond the Story, read Anoushka Antonnette Mathews’ piece on Avijit Mukul Kishore’s opening talk at the event. To learn more about queer artists thinking through the personal, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Sunil Gupta’s exhibition Come Out, Upasana Das’ reflections on Charan Singh’s The Promise of Beauty, Mallika Visvanathan’s interview with Sandeep TK and Veeranganakumari Solanki’s conversation with Fiza Khatri.

All images courtesy of the author.