Love and its Many Spectres: On Payal Kapadia’s Evocative Tapestries

Payal Kapadia’s oeuvre is imbued with a spectral quality, providing a meandering syntax for traversing the registers of loneliness, intimacy, dreams and whispers. Situated at the intersection of the documentary and the fantastical, the narratives often ensue from scavenging or post-photography gestalt exercises. Kapadia’s most recent (and debut) feature film, A Night of Knowing Nothing (2021), which won the Golden Eye award for Best Documentary at the 74th Cannes Film Festival last year, attests to such a process. Produced over five years and made using both shot and collected footage, Kapadia juxtaposes the disintegration of an inter-caste relationship with the meta-archive of student protests in public-funded educational institutions against the current authoritarian regime. The narrative uses an epistolary address as a fictive thread to reflect on the neo-fascist state and its interweaving politics with the relationship. Kapadia’s use of non-digetic sound in this, as well as her preceding short films, is never meant to illustrate but work with the image to evoke a feeling. Atmospheric and punctuated with animated illustrations, her films manifest a symbiosis between human and nature, and a gradual movement towards openly speaking about love as a counter to repression. This is not necessarily romantic love, but a love for the bygone, the inanimate, a memory, or the unknown—this love includes both fear and desire within its ambit.

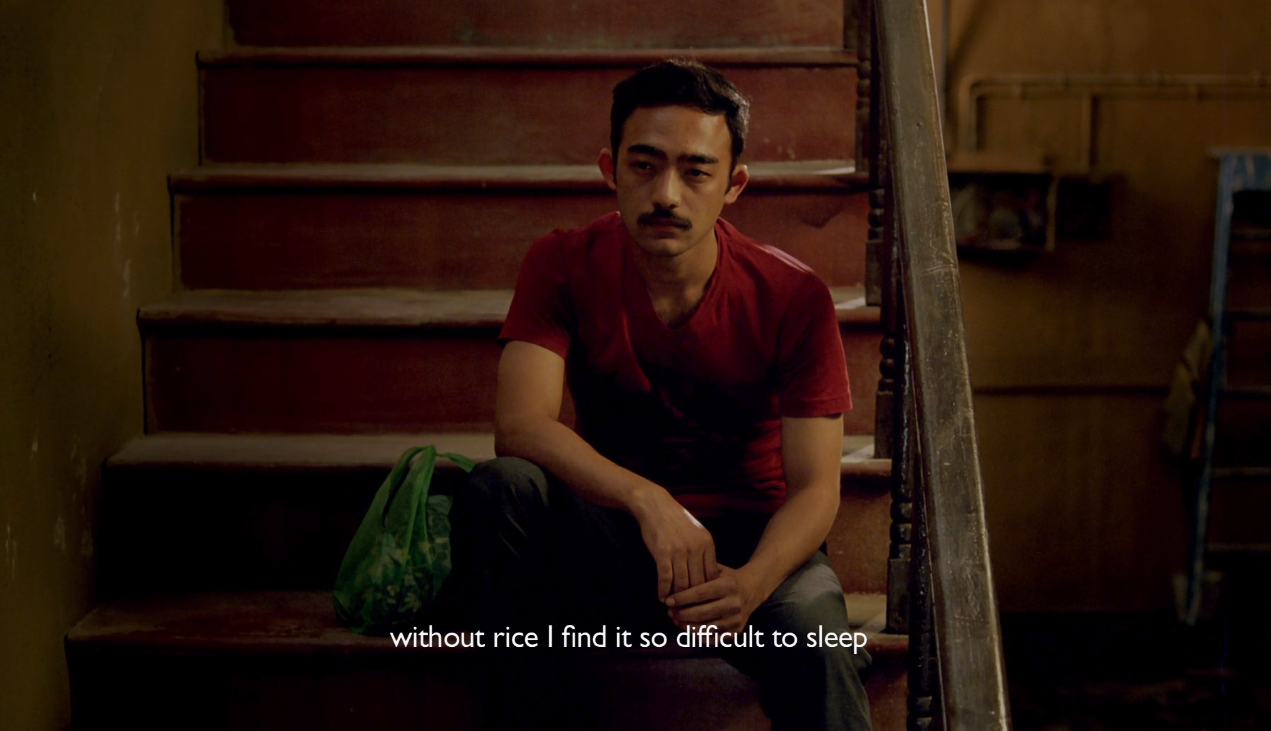

Stills from Afternoon Clouds (Dir. Payal Kapadia. 2017)

In her short, Afternoon Clouds (2016)—which focuses on a day in the lives of an elderly widow Kaki and her young maid Malti—Kapadia also employed epistolary devices to communicate feelings and interpersonal politics against a scape of multilingual intimacies. Malti speaks in constrained Hindi with the former about the mundane objects and events that bind them in soft routines, and switches to easy Nepali while talking to her lover about how she cannot sleep well without a meal of rice, in indication of a habit. This attests to the role of linguistic intimacy in the shaping of interpersonal relationships, confirmed through sparse but excited exchanges in a corridor.

Kapadia talks about her formative observations regarding her late grandmother, who lived a long life alone till her death at the age of 98: “During the last few years, she often spoke about her husband and his visits to her in her delirious states, which made me think. It was not as if they were very loving to each other when he was alive―how then did this ghostly memory arrive?” Kapadia talks about how “loneliness” is an alien sensibility, despite its pulsating reality among Indian women; the feeling then spills beyond the skin and manifests through incorporeal extensions. In the film, Kaki’s loneliness manifests in dreamscapes of bilious pest control fog that also envelops Malti’s lover as he prepares to depart.

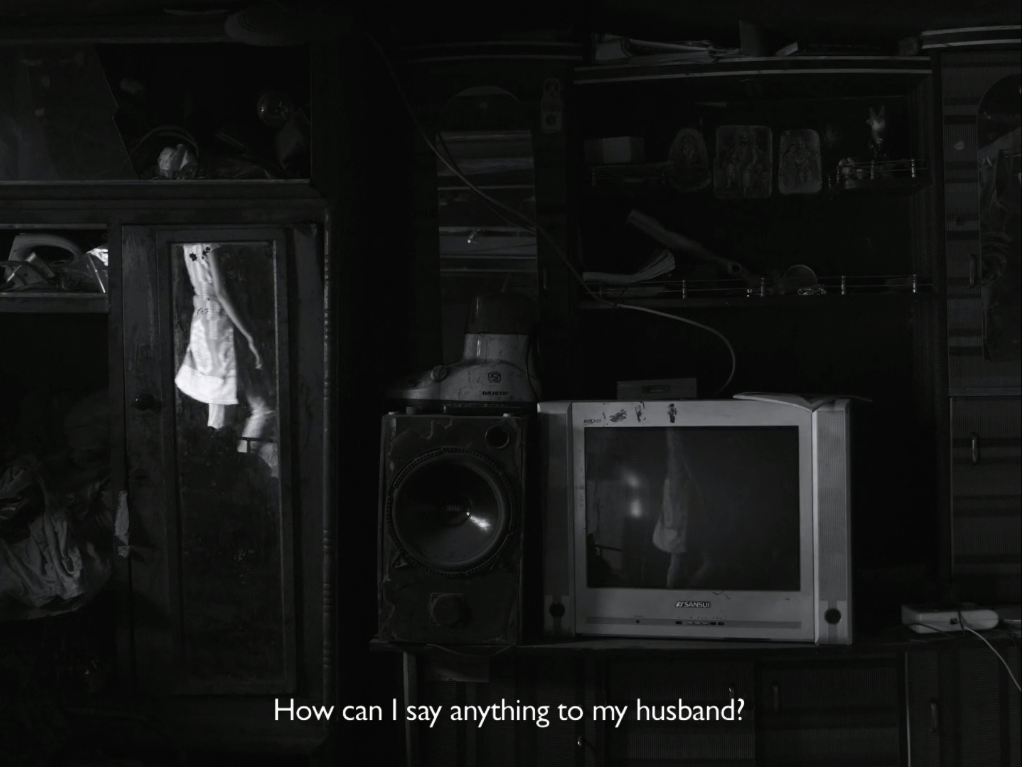

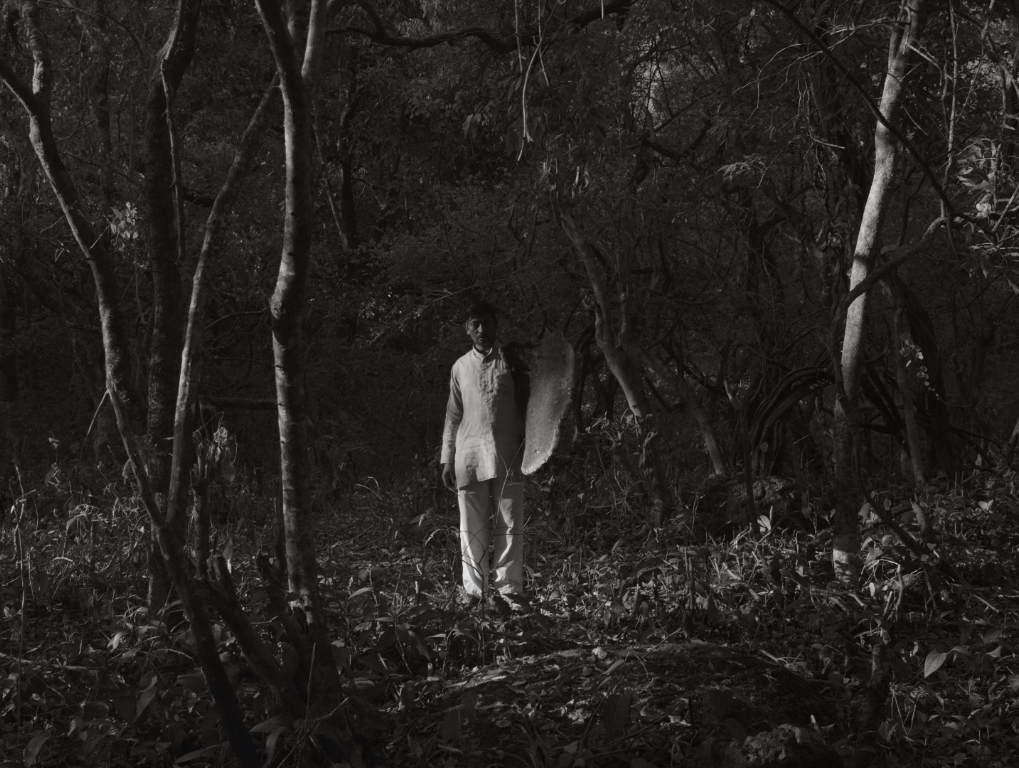

Stills from And What Is the Summer Saying. (Dir. Payal Kapadia. 2018)

This motif of coded exchange and withheld promises percolates into And What is the Summer Saying? (2018), where stories emerge from the depths of the jungles of Bhimashankar, an Adivasi village in Maharashtra. Kapadia notes that the women in the village are married off at extremely young ages to much older men, resulting in a large demographic of widows in the region. The younger men leave the village in search of work as well, due to a lack of opportunities in the locality. As a result, a lot of young women find themselves in similar positions to that of the widows. Kapadia spent her afternoons chatting with them, hoping to understand the loneliness they face while situated at the perimeters of a protected sanctuary that they are entrusted to upkeep. Her observations take shape through summer songs and whispers recorded over the duration of her visit, as the women bared secret desires (including the impulse to eat crabs and roam in the forest), anxieties around married life, and unacknowledged love—all of which were difficult for them to express in the face of gendered (and social) constrictions in a hetero-patriarchal society. In the film, it is the wind blowing over the village that carries these stray strands of conversations to the camera’s ears.

And What is the Summer Saying? also follows the village beekeeper—his gazes, gestures and silent traversals across the forest, pointing to the meandering nature of a regular job. At some point, he becomes one with the landscape in how the jungles absorb him into their fold. A part of Kapadia’s short, The Last Mango Before the Monsoon (2015), is also situated in the forest and shows a team of cameramen setting up heat-imaging cameras on a tree in order to document animal activities at night. In a parallel narrative picturised along the Western Ghats, a woman reminisces about her husband who appeared to her in a dream and spoke about how he would transform into a lion, an elephant, or even another human in his afterlife. A few moments later, an elephant is captured crossing a wooden log on the camera. As the heat captured from the elephant becomes a memory in image, one wonders if the wandering ghost of the deceased man has come to inhabit the frame. The transmutation of beings across human and animal speaks to a primal association premised on intimacy between all life forms. While the woman’s own relationship with nature manifests in her immediate consumption of a mango, the spectral traverses between extractive registers of surveillance in dense foliage and her intimate recalling in a crowded city.

Stills from The Last Mango Before the Monsoon. (Dir. Payal Kapadia. 2015)

Aesthetics and politics coalesce in Kapadia’s cinema and becomes a site of creative re-imagination through the textured use of sound and image. The juxtaposition of non-diegetic sound with image creates new sites of encounters and meaning, with sound often acting as a scaffold for the image. In cinema, time is measured through sound, says Kapadia. The hum of nocturnal life in a forest, the gentle crackle of chillies in hot oil, the measured giggles of young girls as well as the sonorous chants of “Azadi!” among a pulsating crowd are articulated in these narratives in evocative contingencies with the image. Kapadia has spoken about how making a short film is equivalent to writing a haiku—a self-standing unit of expression that resists overt explication. Situated at the intersection of myth, folklore, lived realities and fantasy, her films are light verses of human states and their extended relationships—with, about and emerging from the feeling and the politics of what manifests in these conditions as love.

To read more about docu-films exploring the personal and the political, click here, here, and here.