Turbine Bagh: On Samosa Packets as Blueprints of Dissent

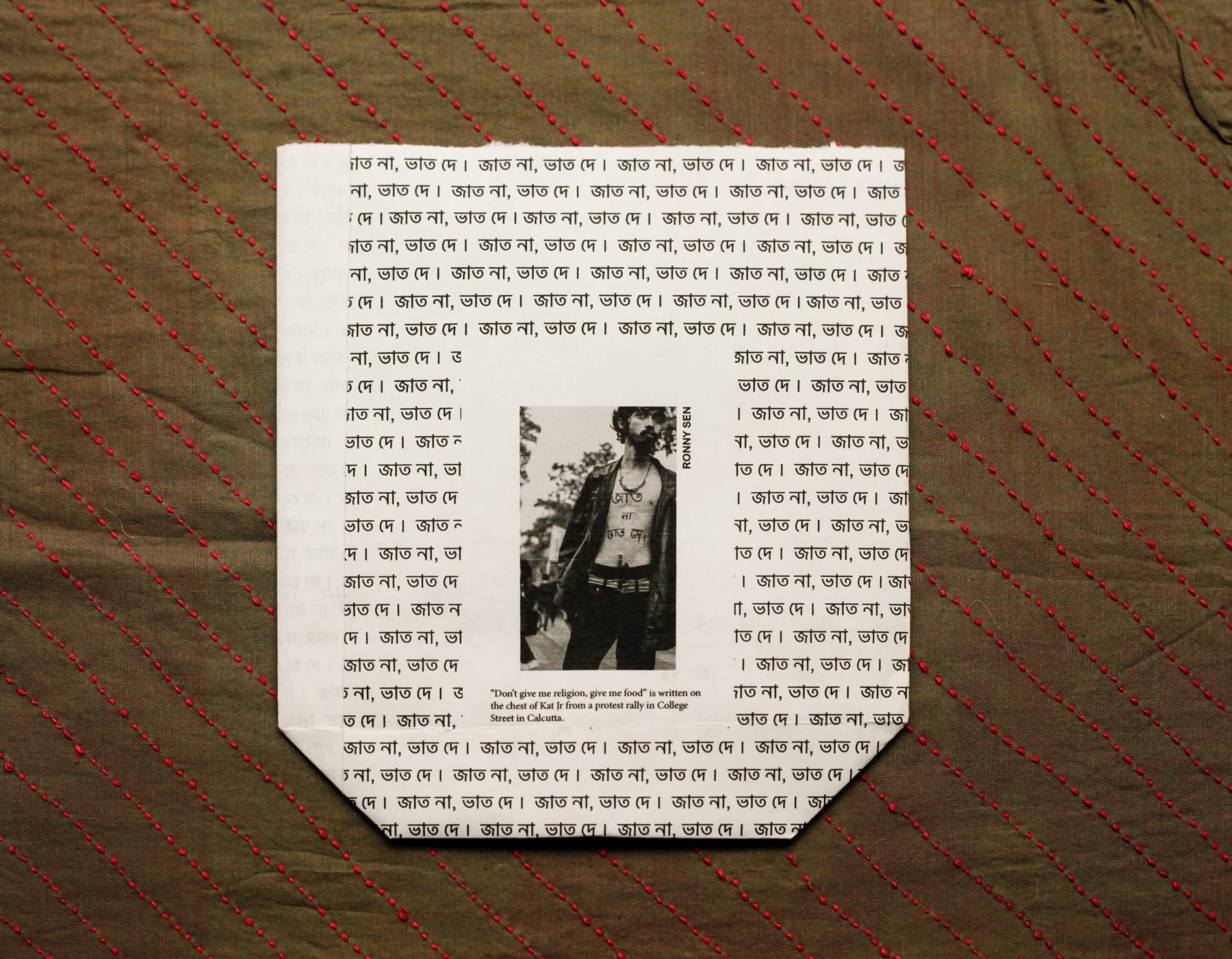

Don’t Give Me Religion, Give Me Food. Samosa packet designed and made by Sofia Karim using photograph by Ronny Sen. (Image by Sofia Karim. 2020. Part of the Turbine Bagh project 2019-ongoing.)

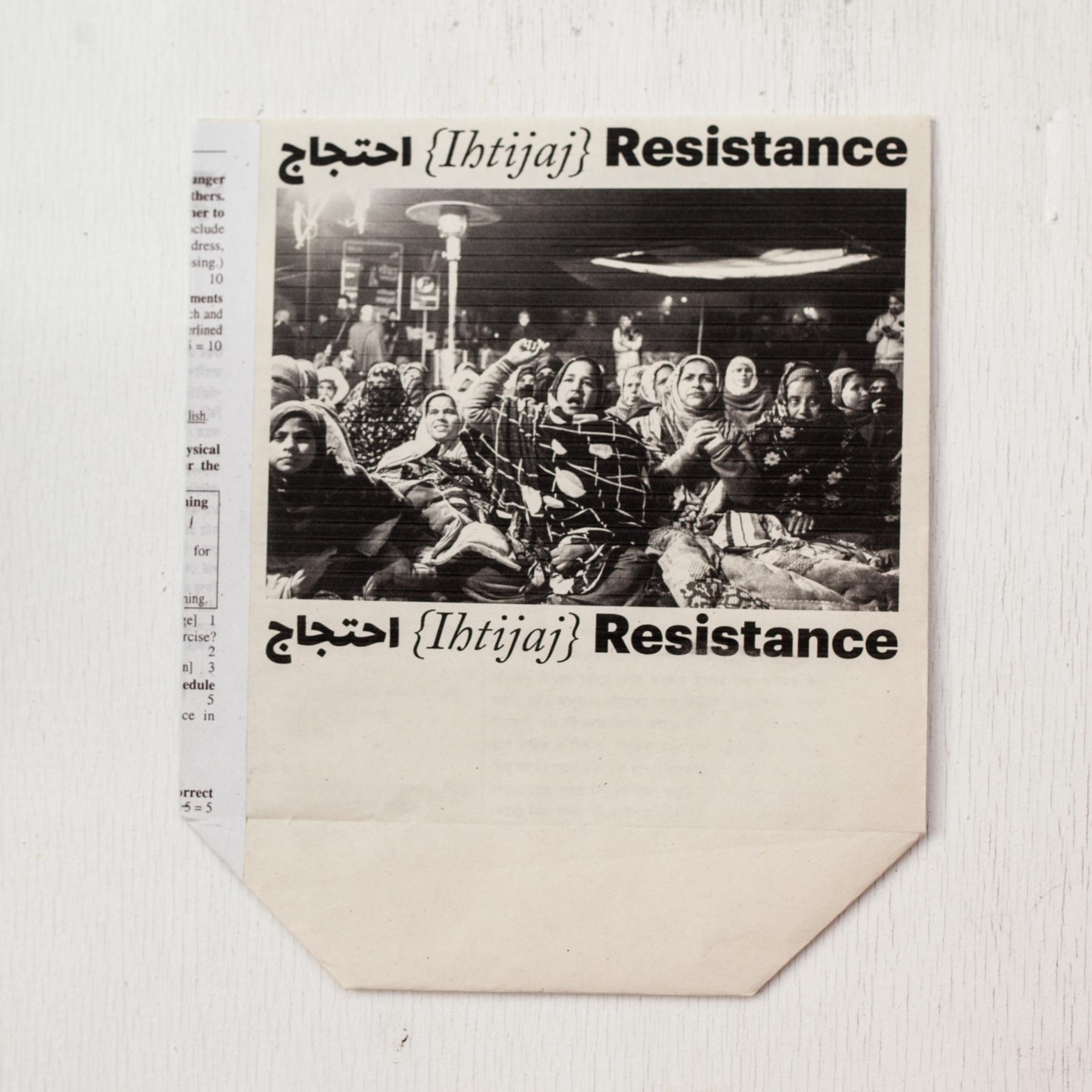

The Turbine Bagh project emerged from an urgency to respond to incidents of mass arrests and incarcerations over the last few years in India and Bangladesh, with both countries currently under neo-fascist regimes. The nomenclature is two-fold, with the prefix coming from the project’s initial plans to be staged as a one-day protest performance on the premises of Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, London, in 2020 (postponed due to the COVID-19 imposed lockdown). The suffix “Bagh” is drawn from Shaheen Bagh—the site of the peaceful mass protests led primarily by Muslim women in Delhi against the Citizenship (Amendment) Act 2019 that threatens to demolish the secular fabric of the Constitution by covertly discriminating against the Muslim population residing in India. Initiated by Sofia Karim, the Turbine Bagh project gained traction through word-of-mouth, staging on museum grounds, social media dissemination and cross-border ally-ship.

“Shaheen Bagh, Inhtijaj, Resistance”. Samosa packet designed and made by Sofia Karim using photograph and graphics by Ali Monis Naqvi. (Image by Sofia Karim. 2020. Part of the Turbine Bagh project 2019-ongoing.)

Karim’s observation of a banal samosa packet in her hand that happened to carry lists of court hearings between the citizens and the state is what led to the inception of the project. The list was a reminder of the numerical enormity of such cases in both India and Bangladesh, and their reduction to a quiet ubiquitous backdrop to daily life. Thus, Karim wondered whether the court listing of her uncle’s case, renowned photojournalist and activist Shahidul Alam, could appear as a statistic on a samosa packet one day as well. Alam had been arrested by the police, and subsequently kept in jail for 107 days on charges of "provocative statements" under the draconian Information Communications Technology Act of Bangladesh. Distressed by this sudden upheaval, Karim began creating her own samosa packets carrying the slogan “Free Shahidul”, campaigning in tandem with the eponymous movement that had already spread across the globe.

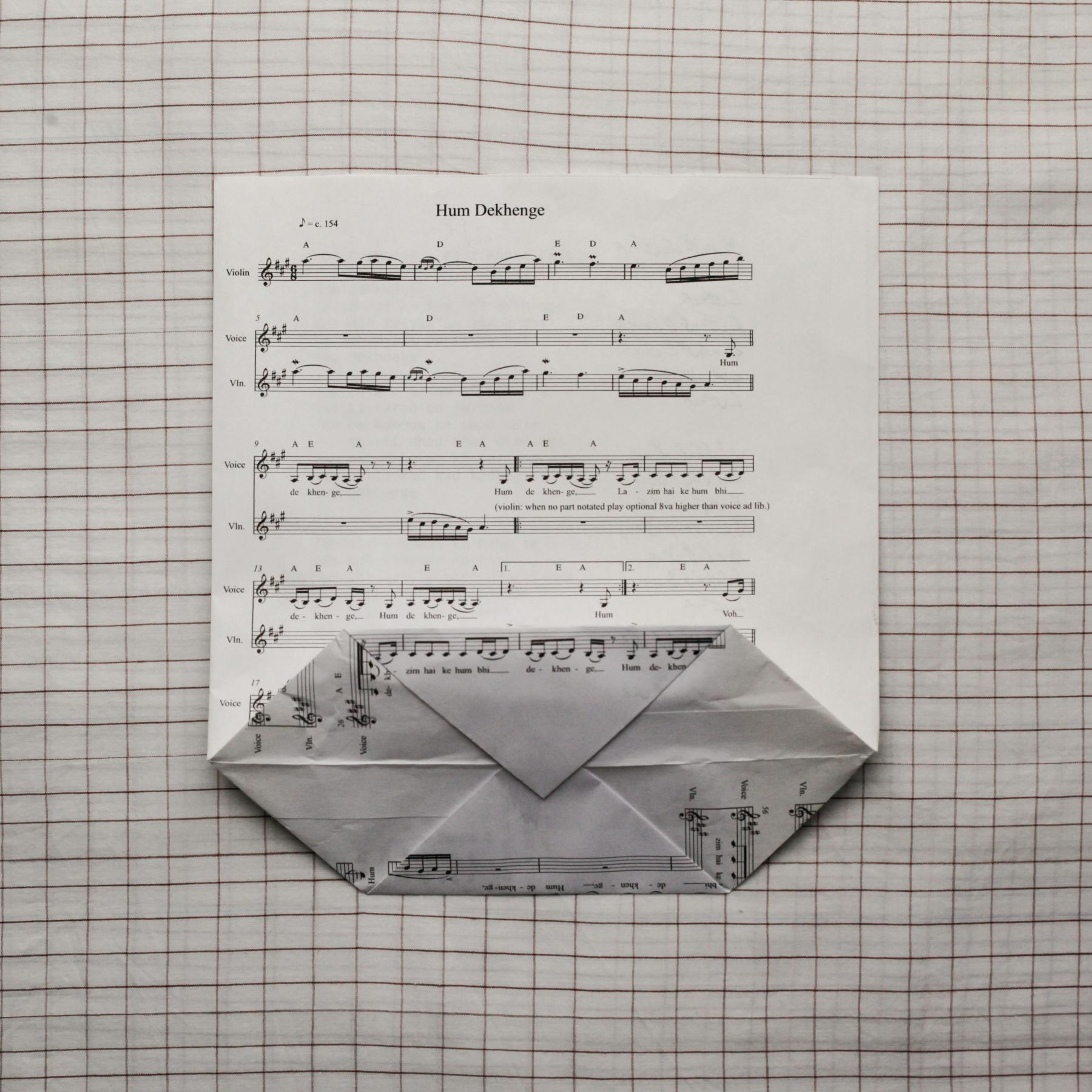

Hum Dekhenge. Featuring musical score by Oliver Weeks. (Image by Sofia Karim. March 2020.)

At a time when the press was heavily censored, the packets became an easy digital conduit for messages of dissent across borders. Perhaps, the centrality of food at Shaheen Bagh as an anchor for congregations also informs the choice of using a samosa packet as protest art. When the common refrain of a protest site is “Have you eaten?” it is evident that the dissent carries the weight of care and community; Karim’s initiative appeals to this sense of solidarity.

Free Umar Khalid. Samosa packet designed and made by Sofia Karim using photographs by Rohit Saha and Ronny Sen. (Image by Sofia Karim. 2020. Part of the Turbine Bagh project 2019-ongoing.)

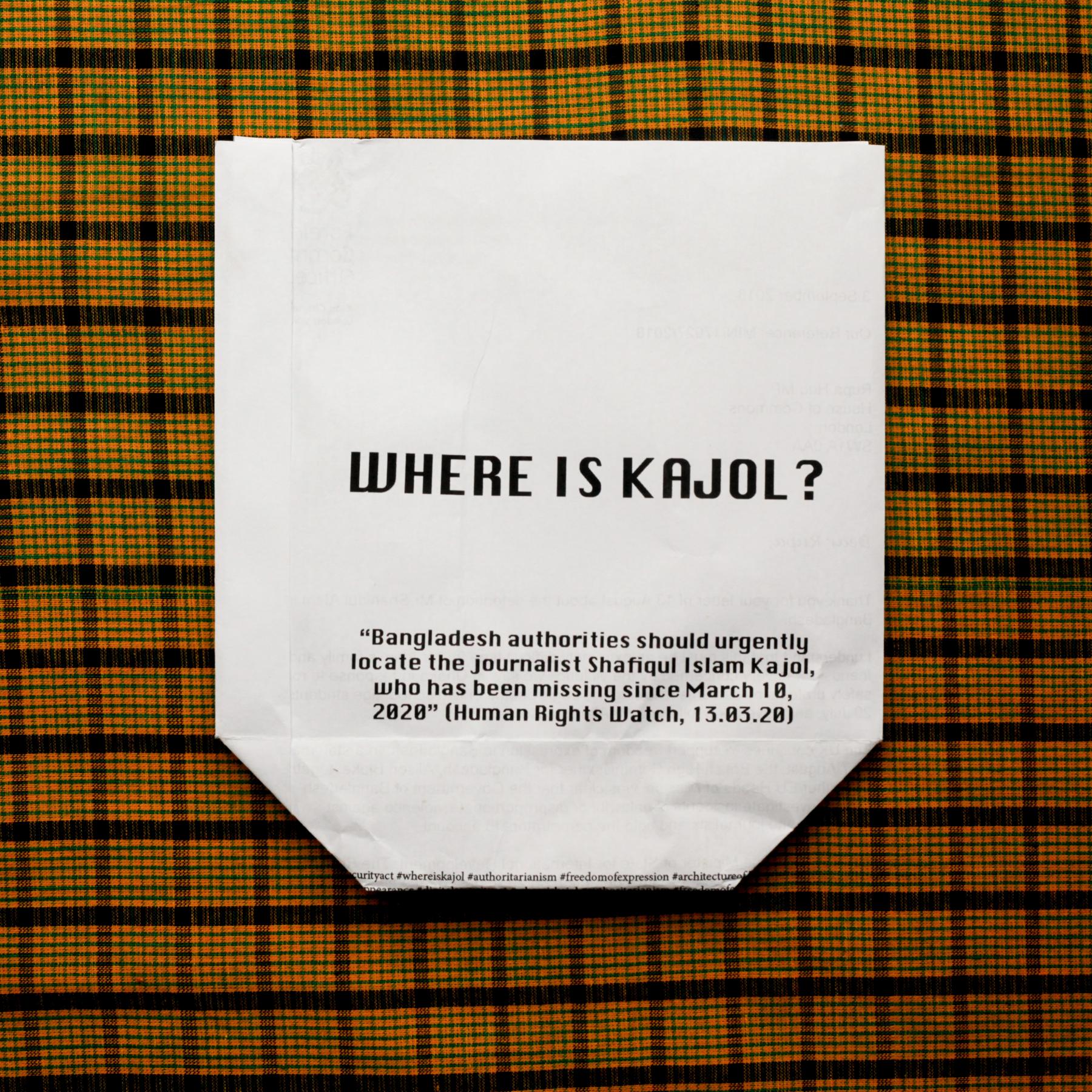

Where is Kajol? Samosa packet designed and made by Sofia Karim and her daughter, Lylah Sanderson. (Image by Sofia Karim. 2020. Part of the Turbine Bagh project 2019-ongoing.)

Constructed from dated newspapers (thereby, carrying a randomised collage of information), the samosa packets essentially serve a utilitarian function: The inexpensive and disposable nature of the paper item also makes it widely distributable, enabling easy access to its surface content. Karim mobilised these factors to print messages and images of dissent on old paper using her mother’s inkjet printer at home, which were then folded to make the packets. As the images gained traction on Instagram, Karim called upon artists, writers, poets and thinkers through an open call to contribute their works to the project. Soon, there was an arsenal of packets calling attention to a wide array of institutional injustices—ranging from the Bhima Koregaon arrests, Umar Khalid’s arrest to the Black Lives Matter movement and demands for Palestinian liberation. Another movement effectively initiated on the platform was the “Free Kajol” campaign, which referred to the disappearance of photojournalist Shafiqul Islam Kajol in Bangladesh. The project has since assumed an adaptable form, mutating with the evolving interests of the participating voices.

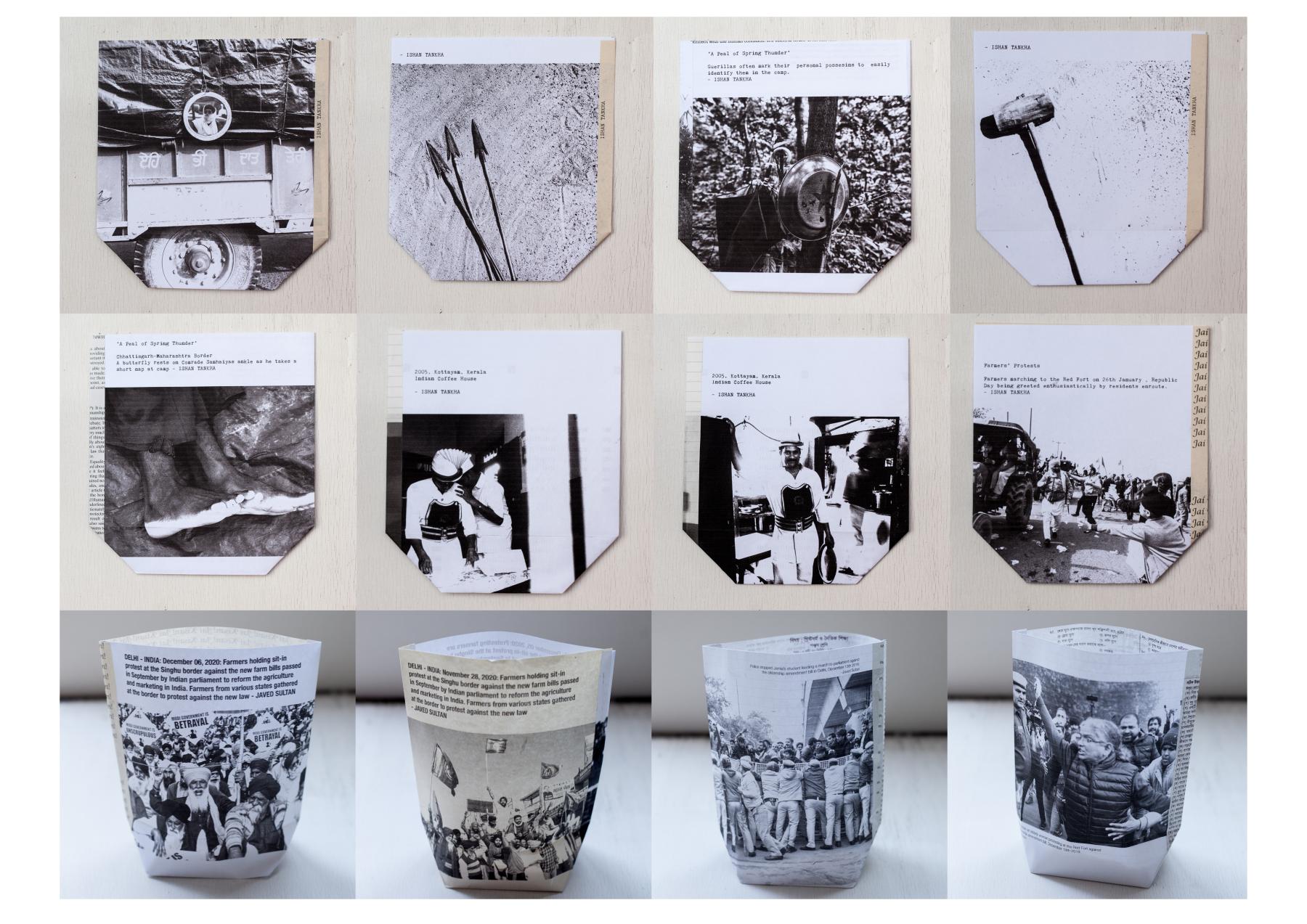

Collection of samosa packets bearing Ishan Tankha and Javed Sultan’s works; samosa packets designed and made by Sofia Karim using photographs by Ishan Tankha and Javed Sultan. (Image by Sofia Karim.)

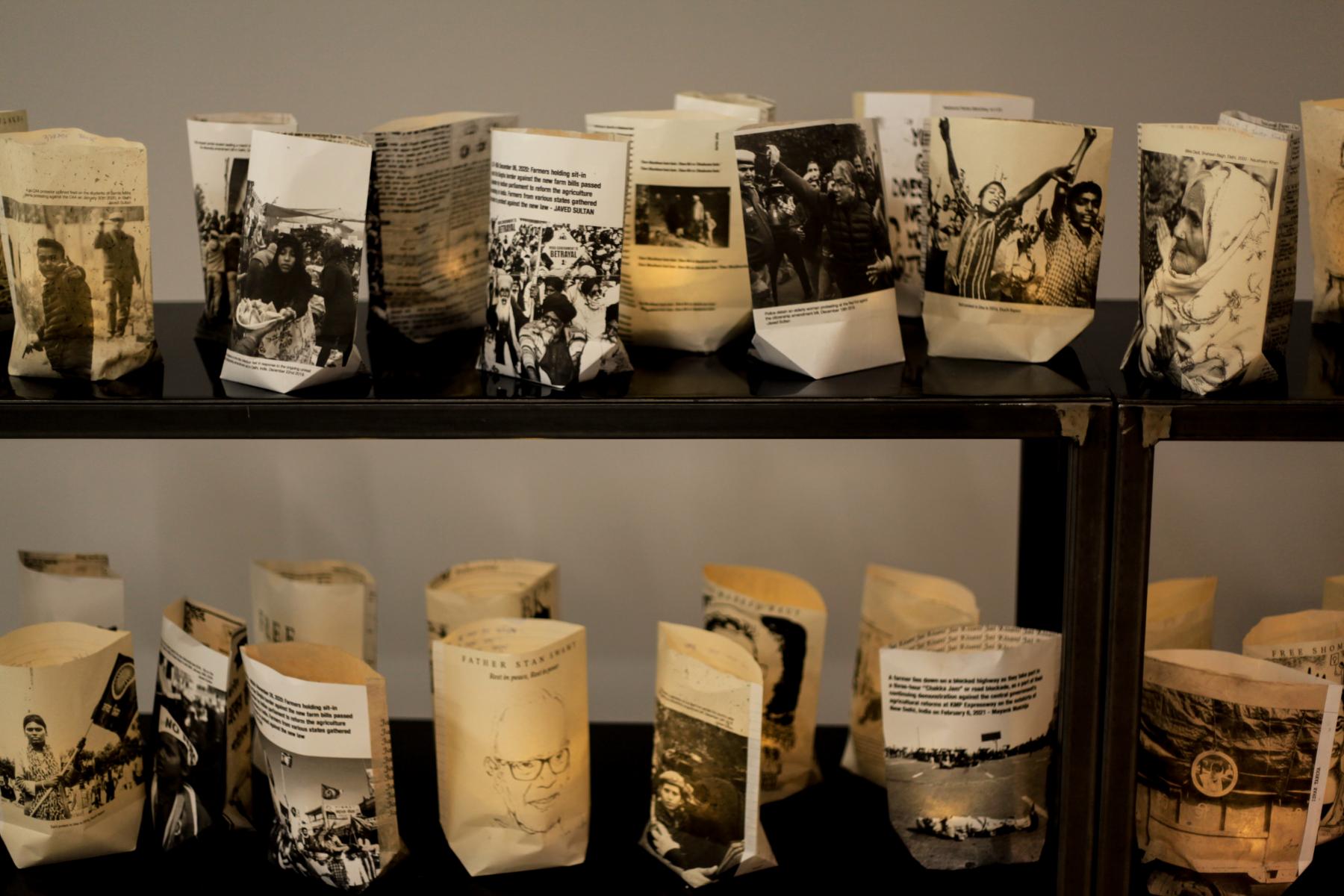

Collection of samosa packets on display. Sofia Karim. Printing Futures exhibition, Documenta 15, curated by Gerhard Steidl, June–September 2022. Turbine Bagh, Inquilab! Image by Sofia Karim.)

As a South Asian diasporic member, Karim channels her hyphenated identity through her activism as a way of staying connected with the region with which she identifies. Furthermore, being an architect, she believes in the affective possibilities of architecture, and its potential to mobilise bodies. Thus, Karim’s profession intimately informs her work as an artist, which becomes apparent in her creation of a series of architectural models based on the oral narratives about the interiors of the Keraniganj Jail, where Alam had been put up. Karim’s activism—founded on drawings, text and images—is centred on the quick realisation of objectives through action premised on collaboration and good faith. The packets were recently exhibited by Karim under the title Turbine Bagh, Inquilab! at Kunsthaus Göttingen, Germany, as part of Printing Futures, Documenta 15, curated by Gerhard Steidl. In this iteration, visitors wrote and signed letters demanding the release of political prisoners such as Anand Teltumbde, which were then forwarded to the concerned prison authorities in India.

While Karim has had to contend with the decision to have an institutional showcase for the packets (which potentially turns them into museum objects), she also believes that this is an effective way to reach diverse audiences. A collection of ninety samosa packets were thus donated for permanent installation at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London—on the express condition that they never enter any fiscal transactions or private collections. The collection serves not only as a record of the ongoing struggles and resistance movements but also stands as a testament to the ways in which artists have campaigned (and continue to do so) for the release of prisoners arrested at the whims of institutional power. Many Western nations, she insists, are still unaware of the threats posed by the authoritarian governments in India and Bangladesh, and the packets have helped create awareness as well as dismantle consolidated notions about South Asia that are far removed from the realities on ground—as is evident in the responses Karim has received to the project. As a resistance movement that continues to thrive through digital channels, to date, the Turbine Bagh project is an alternative initiative in news dissemination that combats state propaganda, which is otherwise equally pervasive on samosa packets.

To read more about collaborative art and protest structures, click here, here and here.