Queering the Canon: Reimagining Art Historical Paradigms

What Do Images Want? Art, Identity, and Difference, an online postgraduate students conference was organised by the Visual Studies department of the School of Arts and Aesthetics, JNU, from 18 to 20 October 2024. Among several interesting panels, the second day had a session titled “Queering the Canon: Reimagining Art Historical Paradigms,” moderated by Vikramaditya Sahai, with presentations by Hritika Kamboj, Mayank Aggarwal and Rayan Chakrabarti.

Screenshot from Hritika Kamboj's presentation.

In her presentation, Kamboj took a close look at the exhibition Dalit Dreamlands: Towards an Anti-Caste Future, curated by Manu Kaur. Described as a “landmark multimedia Dalit art exhibition and dance party,” the exhibition held in the US, saw the coming together of over thirty “marginalised artists from Dalit*, Adivasi*, Bahujan*, Afro-Indian, Indo-Caribbean and Muslim communities to showcase the depths of creativity and community.” Kamboj started her discussion by noting the exhibition’s close alignment with Gail Omvedt’s exploration of the ideas and ideals of eminent anti-caste intellectuals in her book Seeking Begumpura, thus signalling the many possibilities of “queer futurities.” Examining the ways in which the works of artists like Akhil Kang complicated the question of queerness, she showed that “the caste question is not one that is peripheral to the queerness questions,” rather it is co-constitutive of cultural production. For Kamboj, “queering” is reflected as an “imaginative space that allows for dreaming an elsewhere,” “without letting go of intergenerational trauma or the historical burden” of oppression. Reflecting on Shyama Kuver’s work, Kamboj commented on how the body, labour, memory, work and career mobility all come together, resonating with Ambedkar’s words: “being is always becoming.”

Page from Dalit Dreamscapes exhibition brochure.

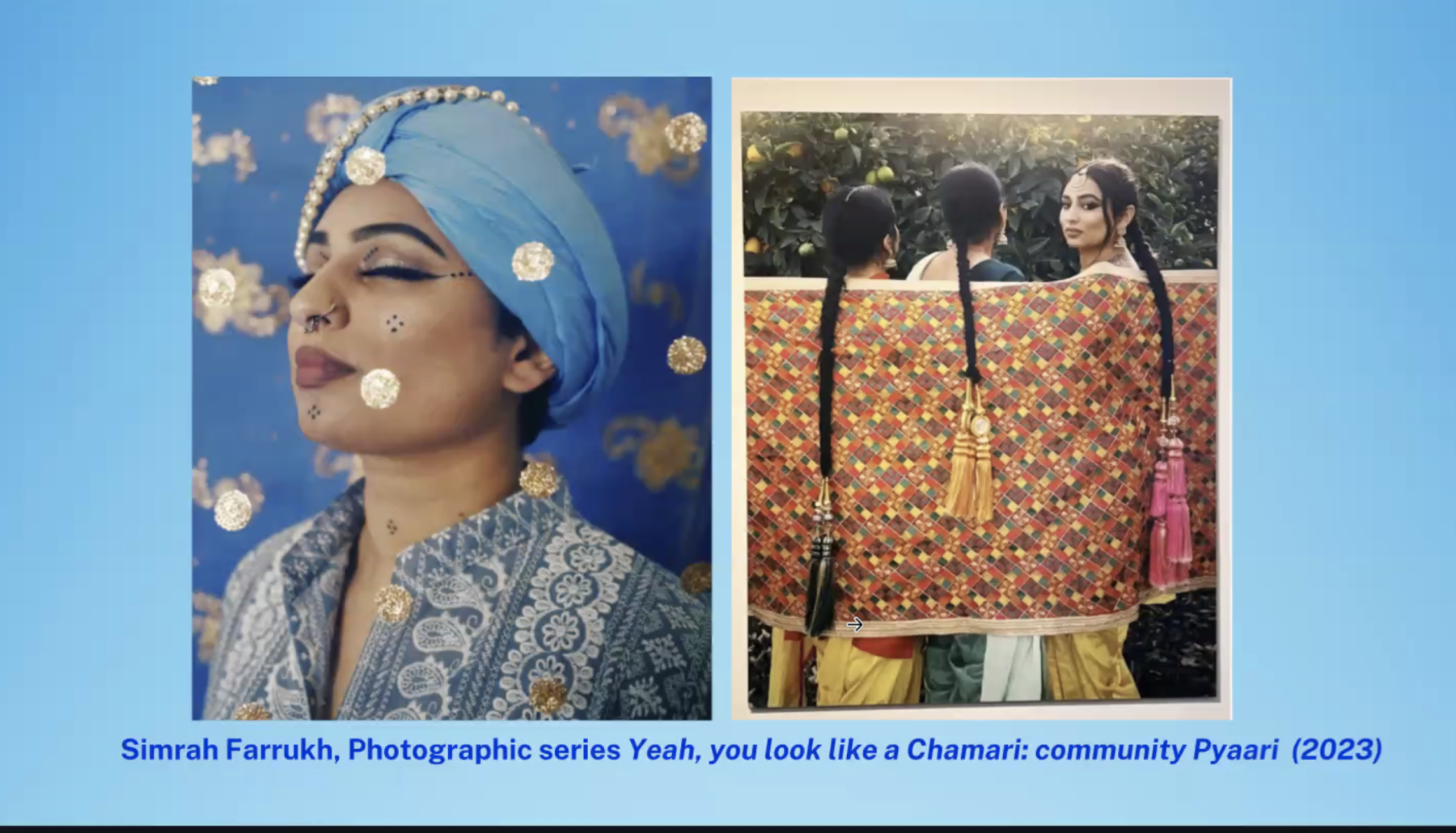

In Simrah Farrukh’s evocative and performative photograph series Yeah you look like a Chamari: Pyara Parivar, Kamboj read the potential of the defiance of voyeurism and the subversion of savarna/white gaze of pity through the visceral joy present in the photographs. It also simultaneously marks what YS Alone calls the “savagery of caste oppression,” according to Kamboj, through its “spectacle” of a “performative display of violence.” Kamboj referenced the works of the Namma Santhosha project, the clay buffalo sculpture by John Spencer Ramachandran, Nrithya Pillai’s dance practice and discourse that questions the ‘cleansing’ of Bharatanatyam through the erasure of its devadasi tradition to highlight forms of social justice through the reclaiming of cultural production, thus constituting affective communities of hope.

Screenshot from Hritika Kamboj's presentation.

Mayank Agarwal presented his ongoing project Queer Childhoods: Image, Memory and Childhood, which deploys “queer listening” to read domestic photography in family albums. By taking something as banal or everyday as the middle-class family photographs of queer individuals, Agarwal looks at the spatio-temporal frame of the image to posit ‘queer’ not as an adjective to childhood but rather as a verb. In doing so, he attempts to take away the passivity of the ‘queer’ child by highlighting body performativity and personal narratives, which end up indexing not only the past but also the queer present/presence. He draws from Mary Ann Doane to look at the ‘traces’ in the photographs that are specific, contingent and mutating, as well as from Marianne Hirsch’s conceptualisation of the ‘familial look’ which frames the gaze as one that is not just of looking but also of being looked at, creating a mutuality in the frame. For instance, Agarwal cites a photograph of an individual and her mother dressed up for a festival. While to an outsider, this might appear to be ‘normal’ or ‘happy,’ the individual remembers the moment as an unpleasant experience, where she was expected to conform to a performed Telugu Brahmin/Brahmanical ideal of femininity. The affective discomfort embedded in the photograph allows Agarwal to indicate towards the contrarian image these individuals have of their childhood selves. He argues this difference perhaps constitutes the ‘punctum’ of these particular photographs.

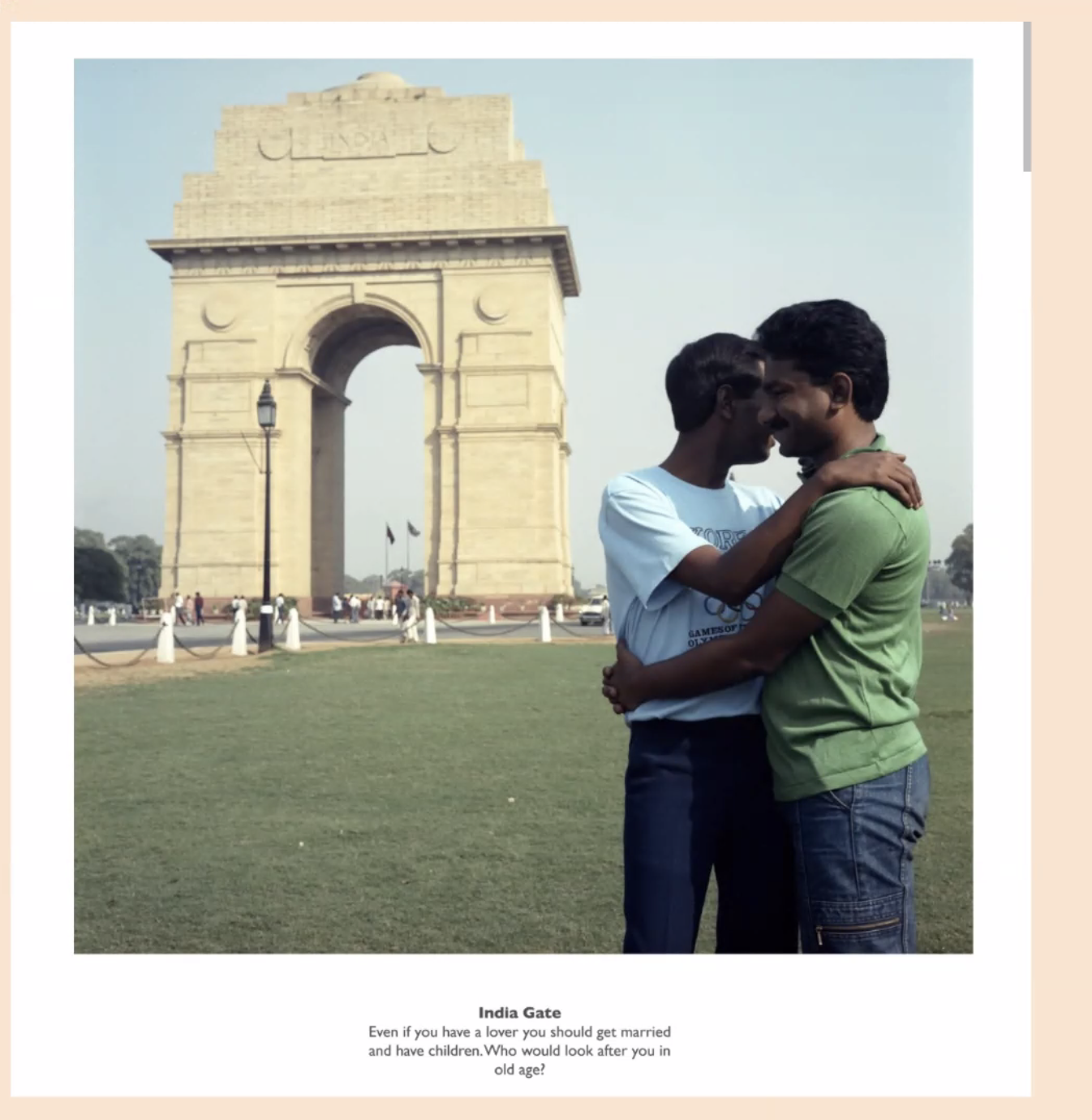

Gupta’s photographs of queer couples juxtaposed with places of national importance (like India Gate) put together a postcolonial queer archive. This archive resists and reverses the colonial imagination engendered by photographs of the same space. Chakrabarti draws from Liam Buckley’s work “Objects of Love and Decay: Colonial Photographs in a Postcolonial Archive” to examine the afterlife of the photographs. For, if the colonial photographs foregrounded national pride where people appeared merely as figures to mark scale, in Gupta’s production of the queer image—in the staged and documentary form, for instance, in his photograph series like Mr Malhotra’s Party and Exiles etc.—both the affective daily lives of queer individuals and the performativity of the trans body work in tandem to produce and subvert the colonial archive.

"India Gate" from Sunil Gupta's series Exiles (1986—87). Image courtesy of the artist.

The presentations generated a discussion around questions of visuality and queerness, the possible multiple meanings of childhood photographs, and the potentialities in ‘listening’ to photographs. As queer itineraries of knowledge produced on visualities, the panel helped think about radical modes of address and resistance in novel ways.

To learn more about artists exploring queerness through their work, read Upasana Das’ essay on Charan Singh’s performative photographs, Mallika Visvanathan's interview with Sandeep TK and Alfa Shakya's curated album of Arhant Shreshta's work. To learn more about Sunil Gupta's work, read Annalisa Mansukhani's review of the exhibition Come Out (2024), Samira Bose’s reflections on a panel discussion on Archival Futures and Parth Rahatekar's response to Sunil Gupta's Cruising 1960s, Delhi.

All images are courtesy of the panelists, unless mentioned otherwise.