A Tradition of Resilience: Aditi Maddali’s Songs of Our Soil

India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) presented the three-day festival Past Forward: The Pleasure, Purpose and Practice of Arts Research at the Bangalore International Centre on 25–27 October 2024 featuring panel discussions, workshops, performances, exhibitions and film screenings. Aditi Maddali’s Songs of Our Soil (Pani Paata Poratam, 2019), supported by a grant from IFA under the Arts Research Programme and screened on Day 1 and 2 of the event, is a result of her extensive research on the women of Telangana and the agricultural tradition of Uyyala songs which express their resilience and resistance.

Women collectively partaking in the Uyyalo tradition while working in the fields.

“Uyyala” literally translates to “swing”, the refrain signifies “sleep” and, by association, “to wake.” It assumes many forms responding to the circumstances—lullabies, devotional songs, festival celebrations, occupational songs and calls for resistance. Belonging to a rich oral agricultural tradition passed down through generations of women, these songs act as a medium for the women to bear and share their burdens as well as express their desires, turning the songs into a device to mobilise people’s sentiments. If the rhythm and words in these songs complement movements in the field, the hard labour involved finds alleviation in the songs filling the air and our frame.

These songs encompass various themes such as their social relations and connection with agriculture.

The film introduces us to various women across Telangana who are in the process of losing their homes, land and villages to India’s largest artificial reservoir, the Mallana Sagar, inaugurated in 2022 under the Kaleshwaram Lift Irrigation Project (KLIP) and responsible for submerging fourteen villages and 12 lakh acres of land. The documentary follows women demanding long-overdue compensation despite the evacuation of the villages three years prior. For the women protesting the loss of their land, losing their villages means the loss of a home, livelihoods and a connection to nature; this displacement compromises their lineage and dissolves community.

Lakshmi recalling experiencing police brutality in the protests to save their village.

Drawing a thread highlighting women’s experiences in people’s movements against feudal-colonial rule across time in Telangana, the film documents women such as Sughuna, who reminisces about her involvement in the Telangana People’s Struggle from 1948 to 1951. In line with communist party ideology, which advocated classlessness and equality for all—or land distribution—the women sang songs written by party members in various collectives of children, farmers, women and labour unions that sprouted under the Andhra Maha Sabha. But not only were songs written from above different from those coming from below, the cultural differences between the leaders and masses were irreconcilable, particularly along the lines of caste. Thus, when the movement ended, the leaders—having more in common with the landlords—insisted that the women now return to unwelcoming homes.

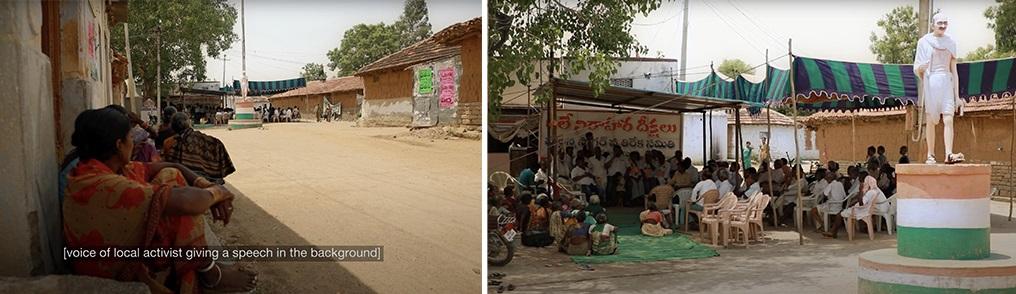

A protest meeting where men are seated on chairs while women are relegated to the side.

Scholar Gogu Shyamala contextualises the role of the tradition of songs in women’s lives as reflections on social relations, economic struggles, their bond with the land and the village, nature and each other. The songs not only reflect their understanding of the complex domains of caste, class and gender but are also a source of strength, assuaging their hard lives by providing an outlet against their exploitation. These songs, born in the field, are a symbol of their resilience and resistance. Highlighting the lacunae in history writing, Shyamala implores researchers to go to the field to expose the limitations and uncover buried stories. Women form the backbone of people’s movements, she reminds us, sacrificing the most during and after, though they are seldom written about.

Dalit feminist scholar Gogu Shyamala providing background to the political movements in Telangana.

But if the tradition is weaponised by the marginalised as a tool to negotiate with their oppressors, this cultural tradition is slowly undergoing depoliticisation and aestheticisation. As Shyamala laments, the landed gentry have built cultural hegemony through political power to enter the world of films, and possessing the ability to mobilise resources, they exploit others’ labour for the ideation of songs and scripts. Thus, songs taken from the people are stripped of all depth and meaning, recycled and used in mainstream cinema, where they are sold back to the people themselves for immense profits. The culture of commodification and consumption we participate in is responsible for the alienation of the people to whom this cultural tradition belongs, thus draining their potential as creators.

Maddali asks Sughana if they wrote songs about women.

Moreover, classifying the tradition as folk culture deliberately disregards its roots, thus, subduing any radical potency while rendering it defenseless to commercial exploitation in representations in the mainstream. In highlighting the parasitic relationship between contemporary cultural production and oral tradition categorised under folk culture, Aditi Maddali’s documentary is a significant intervention recovering women’s experiences hidden within grand narratives of resistance from the past to the present.

To learn more about women farmers and labourers, read Mallika Visvanathan’s interview with Kinshuk Surjan on his film Marching in the Dark (2024), Ankan Kazi's reflections on P. Sainath’s exhibition Visible Work, Invisible Women: Women and Work in Rural India (2021), Gulmehar Dhillon’s curated album from M. Palanikumar’s work on the seaweed farmers of Tamil Nadu (2019) and Najrin Islam’s conversation with Renluka Maharaj on reclaiming the history of Indian female indentured labourers.

All images are stills from Songs of Our Soil (Pani Paata Poratam, 2019) by Aditi Maddali. Images courtesy of the director.