Community, Craft and Legacy: Casting Music and Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley

As part of the India Foundation for the Arts (IFA) event Past Forward: The Pleasure, Purpose and Practice of Arts Research, conducted from 25–27 October 2024, two of the films showcased and produced with the support of grants from IFA's Arts Research Programme focus on communities struggling to achieve social recognition for their mastery of traditional crafts.

In Casting Music (2016), Ashok Maridas follows the members of the Savita Samaj in Karnataka who face caste discrimination despite musical contributions as nadaswaram players. Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi’s The Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley (2024) locates the community of forty craftspersons producing custom-made footwear within the past and present of the social milieu of Dehradun and Mussoorie.

Nadaswaram players practising atop a hill; open spaces are crucial to mastering the instrument. (Still from Casting Music [2016] by Ashok Maridas. Image courtesy of the director.)

In Karnataka, the nadaswaram is played by members of the Savita Samaj, who are barbers by profession, belonging to the Nai caste. A double reed wind instrument, the nadaswaram is touted to be one of the loudest non-brass instruments. Part of the mangal vadyam, the instrument grants permission for a ritual to proceed by sanctifying the occasion and making it “auspicious.”

Nadaswaram maestro Shri KS Mani narrating how he came to learn under his upper caste guru. (Still from Casting Music [2016] by Ashok Maridas. Image courtesy of the director.)

As TM Krishna says in Classically Yours (2016), “It was from the aesthetic interactions between the Isai Vellalars, Devadasis and the Brahmins that Karnatik music evolved into its present form.” However, he continues to argue that the socio-political landscape of the early twentieth century resulted in “Karnatik music becoming almost a monopoly of the Brahmins.” Distinctions such as “classical” necessarily keep the marginalised practitioner at a distance from what is deemed to be “culture.”

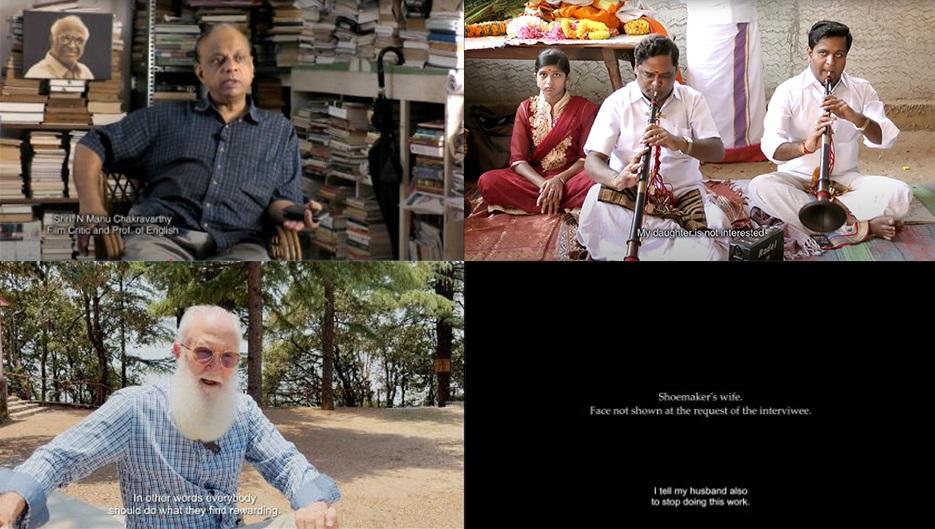

In the film, Professor N. Manu Chakravarthy contends that the equality that existed in the dynamics of creative exchanges between practitioners and instruments, within musical traditions included in the repository that now forms the “classical,” had little bearing on unequal social hierarchy. Veneration accorded to the instrument did not translate to its practitioners, who are often denied a place to eat alongside the guests. Maridas records varied responses within the community to caste-based oppression. He dialogues the contradictions through the film. Claims of ridding oneself of caste discrimination through economic means come at the cost of shedding one’s cultural roots. Capitalism and urban relocation offer a route for the Savita Samaj barbers seeking social mobility by working in modern saloons.

Nadaswaram maestro Shri KS Mani narrating how he came to learn under his upper caste guru. (Still from Casting Music [2016] by Ashok Maridas. Image courtesy of the director.)

The evolution of capitalism and urbanisation in the Doon Valley has thus far only impeded our next film’s protagonists. Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi’s Last Shoemakers begins with a montage framing custom-made shoes across scenic settings followed by prominent voices from the region chronicling the importance of the craft and its community. The trade flourished under the patronage of the British-Indian military and boarding schools. Various craftspersons who found a home here are those who migrated from central India in the nineteenth century, fleeing caste discrimination. Another significant community of shoe-makers are migrants who fled to India when mainland China started encroaching upon present-day Taiwan. Despite the departure of the Indian-Chinese community in the 2000s, fond memories of Chinese shoemakers imprint the region. Unlike their mass-produced counterparts, customised handmade shoes could cater to those with special orthopaedic needs.

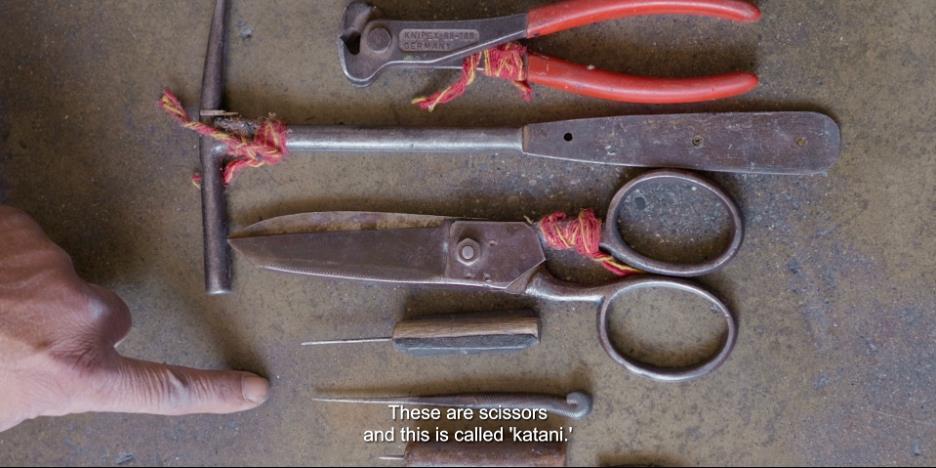

A memorable shot naming all the equipment in the shoemaker’s arsenal. (Still from The Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley [2024] by Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi. Images courtesy of the directors.)

The knowledge inherent in the shoemakers’ labour practices such as the importance of sitting on the ground versus a chair and an integral use of the feet is priceless to researchers in the field of design. Stills from The Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley (2024) by Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi. Images courtesy of the directors.)

The profession locates the caste of the workers as their skill is reduced to comments such as “mochi ki dukaan” (shoemaker's shop), hindering social mobility. Future generations are unwilling to continue their community legacy due to the lack of social recognition in addition to its diminishing economic viability. Burgeoning tourism in the region brings people on short vacations who do not have the time or patience to commission a custom-made shoe. Except for a few loyal customers, most people prefer the convenience offered by branded, ready-made shoes. Craftspersons in the film blame their marginalisation in the market on processes of urbanisation and globalisation as people have stopped physically coming to stores due to the rise of digital commerce. In the wake of government apathy and disinclined future generations, indigenous technologies and knowledge systems realised through practical means in the shoe-making tradition could disappear entirely.

The entire weight of the body is employed in crafting the shoe. Multiple sequences in the film break down the shoemaking process to highlight the knowledge transmitted generationally. (Stills from The Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley [2024] by Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi. Images courtesy of the directors.)

Both films delve deep into the genealogy, pedagogy and social history of the craft traditions they document in order to privilege the respective community’s voices. The music of the nadaswaram, in practice and performance, forms an entrancing soundtrack. Maridas slows the moving image to capture the dexterity of the finger movements, thus displaying the complexity of the skill. Quick cuts detailing the various steps of manufacturing customised footwear impart an energy and rhythm to the movie. Close-ups of hands and feet manipulating the material into the desired product bring the craft to life. And yet, N. Manu Chakravarthy in Casting Music and Joseph Alter in Last Shoemakers both stress that the burden of preserving the tradition cannot fall squarely on the community’s shoulders. Future generations must follow their own desired paths of social mobility.

(Above: Stills from Casting Music [2016] by Ashok Maridas. Below: Stills from The Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley [2024] by Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi. Images courtesy of the respective directors.)

To learn more about other screenings as part of Past Forward, read Vishal George’s reflections on Aditi Maddali’s Songs of Our Soil (2019). To read more about labour practices, read Gulmehar Dhillon’s curated album from Palani Kumar’s documentation of manual scavenging in Tamil Nadu and Kamayani Sharma’s article on Megha Acharya’s Meelon Dur, which follows brickworkers from Bundelkhand to Uttar Pradesh.