Cycles of Labour: On Meelon Dur by Megha Acharya

Bricks are dried, stacked and arranged beautifully in the sun, anticipating the buildings they are meant to become a part of. On the horizon, fumes billow out of tall, columnar chimneys. Triangular chinks, formed by the bricked walls of temporary homes, allow slivers of light in. At night, bulbs and fires offer frugal illumination inside these homes and on the brickyard.

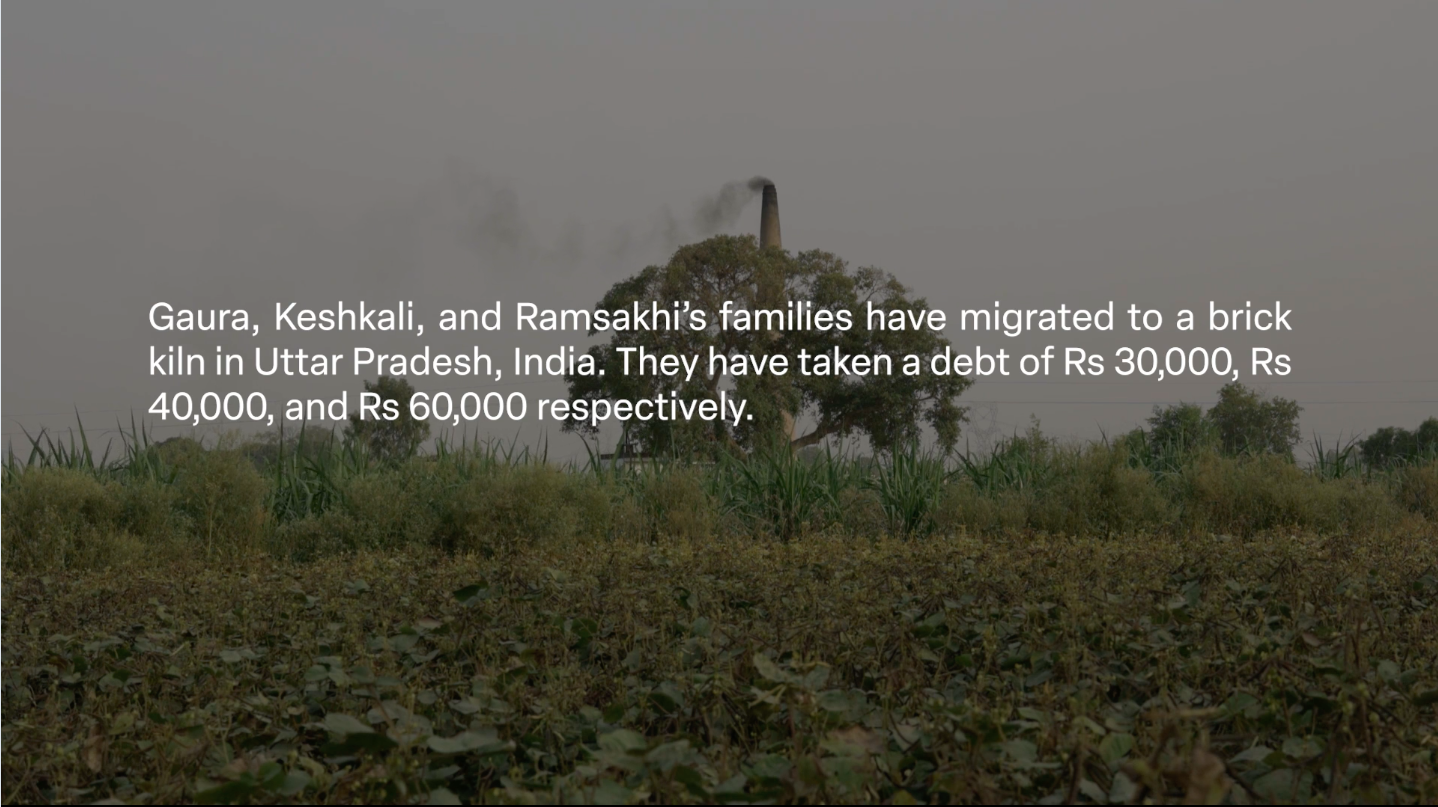

This is the perpetually temporary world of India’s brickmakers, lakhs of whom annually migrate from their villages to work in kilns in other states under inhumane conditions of debt bondage. From the arid Bundelkhand region, which experiences high rates of migration in general, many families journey to distant areas to work in brick kilns. Megha Acharya’s Meelon Dur (Miles Away, 2023) observes three such migrant families who journeyed from Bundelkhand to labour in a brick factory in Uttar Pradesh. The documentary originated from a study by academics Paula Chakravartty and Michelle Buckley, in association with Khabar Lahariya, an independent rural newspaper, and was filmed from November 2021 to June 2022. As they conducted research and prepared for filming, Acharya and Bundeli-speaking associate director Geeta Devi found their focus in the stories of Gaura, Keshkali and Ramsakhi. The women and their families, each in tens of thousands of rupees worth of debt, spent eight months paying it off at exploitatively low prices of labour.

As a record of the daily grind in a brickyard, Meelon Dur brings to mind Chircales (The Brickmakers, 1972), a Colombian documentary about a brickmaker family eking out a living on the outskirts of Bogotá. For those on the margins, little seems to have changed in the fifty years between the two documentaries—the health and safety hazards, the sense of political disenfranchisement and the confinement of their field of view (and, by extension, ours) to a skyline dominated by the chimney tower. The tedium and toil of manual brick making unfolds in the narrative through longshots of the brick piles, midshots of workers framed against the quarry and hunched before the brickworks, and close-ups of feet sunk in wet earth and hands engaged in the hardscrabble of pugging and moulding to depict the tedium and toil of manual brick making. But even bare life contains staccato temporalities of rest—children play, festivals are celebrated and company is enjoyed.

Scenes of labour are interspersed with the protagonists’ “time off.” Hands in particular become a motif, a continuum that connects the time of work and the time of rest: the plying of wet earth rhyming with the kneading of batter for sweetmeats, and the stuffing of brick moulds mimicking the stuffing of samosas. Filming when work stopped—in January, as rain poured, and in March, during the Holi season—afforded the filmmakers the chance to observe the idle and social time of the protagonist families. The quotidian nature of endurance is something Acharya explored in Sudhamayee (Laced with the Nectar of Life, 2019), her short about a woman living with chronic illness, tracing the shape of time experienced differently from the abled. In Meelon Dur, we see workers partaking in pleasures such as buying anklets and flying kites. By chronicling the free time of brick workers, among the most exploited workers in India’s labour sector, the documentary offers a critique of the material regime circumscribing their lives. In its record of the women’s evening addas and Holi celebrations, the film also alludes to the building of community, and perhaps even solidarity, as an antidote to entrenched structures of oppression. As the women celebrate Holi with each other, a young brickmaker says, “Here at the kiln, there are many women, so we’re able to play Holi. Back at our in-laws’, whom do we play Holi with? Here we have [the] independence to play Holi.”

Along with the interviews, the diegetic soundscapes of Meelon Dur allow Gaura, Keshkali and Ramsakhi to bring viewers into their space on their terms. What they hear is what we hear—the sound of their world punctuated by plops of brickmaking. Commenting on the work of the film’s sound designer, Sridhar Varadarajan, Acharya says, “The sound of bricks conveys many things—the passage of time, monotony and rhythm in their work…the mood inside the kiln (as it changes every month).” But just as with the visuals, the rhythmic sound of brick work is interwoven with the bricolage of radio music, political campaign advertisements and the ambient sounds of nature. Reminiscent of the migrant music of Surabhi Sharma’s Bidesia in Bambai (2013), folk pop songs playing in the background of work gesture towards the home left behind and off screen. The sounds of cicadas, raindrops, and the wind fill the restorative silence of “free time”—nature’s interruption of labour is a reminder of the imbrication of the ecological and the economic.

As the documentary concludes, we are told that at the season’s end, the three families returned to Bundelkhand with their meagre earnings. The respite is short-lived—the final scene shows Gaura’s family on their way back to a brickyard. The low-angle shot of the tree canopy under which their tempo trundles obscures the sky across which smoke from the kiln chimney will drift. The cycle continues, meelon dur.

Meelon Dur (Miles Away) is screening as part of the Kolkata People’s Festival, taking place between 24–28 January 2024.

To learn more about the films being screened at KPFF 2024, read Shranup Tandukar’s review of Dholpatan (No Winter Holidays, 2023), Ankan Kazi’s essays on In Search of Ajantrik (2023) by Meghnath and Kayo Kayo Colour? (2023) by Shahrukhkhan Chavada, and Santasil Mallik's essay on And, Towards Happy Alleys (2023) by Sreemoyee Singh. You can also revisit the In Person conversations with Shahrukhkhan Chavada and Wafa Refai on their film Kayo Kayo Colour? and Nishtha Jain on her film The Golden Thread.

All images from Meelon Dur (Miles Away, 2023) by Megha Acharya. Images courtesy of the director and the Kolkata People’s Film Festival.