Foregrounding the Background: Of Dancers, Princely States and Unwritten Histories

On 27 October 2024, Siddhi Goel and C. Yamini Krishna made presentations as part of the panel: “Forgotten Genres, Publics and Practices: The Understated Ecosystem of Indian Cinema” at IFA’s Past Forward: The Pleasure, Purpose and Practice of Arts Research.

Siddhi Goel presenting the ecosystem of Kathak dancers in the Bombay film industry. (Photo by Anoushka A. Mathews)

The presentation by Goel on the ecosystem of background Kathak dancers in the Bombay film industry and Krishna on the scant histories of films from the princely states illustrated cinema beyond the mainstream to uncover narratives and histories that have been relegated to the margins. The research projects are akin to one another in that they attempt to piece together alternate film histories to point to the larger gaps that exist in their telling and remembering. In doing so, they document the undocumented and make visible the invisible.

C. Yamini Krishna with a map of the region covered by the princely states. (Photo by Anoushka A. Mathews)

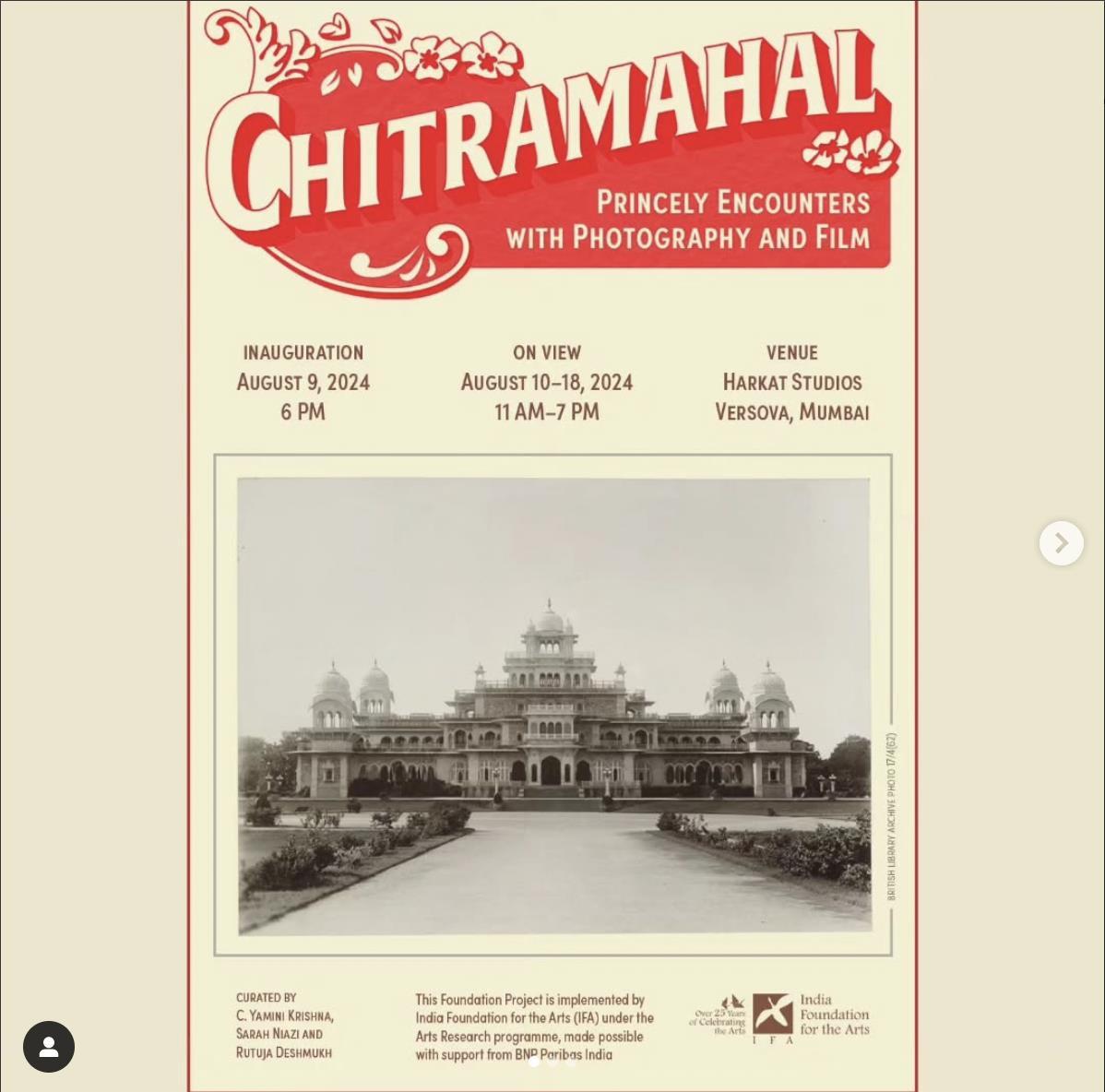

Krishna introduced us to a world of cinema from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries that existed beyond Bombay and was supported under the patronage of the princely states. Her research culminated in an exhibition titled Chitramahal which weaves together accounts of cinema that emerged from the princely states of Indore, Kolhapur, Madras, Calcutta, Hyderabad and Jaipur. She shows us that kings, princes, nobles and prime ministers not only funded films within their dominions but were also known to fund filmmakers in the Bombay film industry as well as in Europe.

Poster for the exhibition Chitramahal (Source: IFA’s Instagram)

Across princely states, palaces were offered as locations for crews to shoot in, and the king’s army also often featured in these films. These visuals constitute part of the larger Oriental image circulating out of India and even within its confines. Krishna makes the argument that those represented in these images, especially those in positions of power like royalty and nobility, were not passive bystanders in the production of the Oriental image, but actively contributed to its production. For instance, Himanshu Rai’s collaboration with German director Franz Osten for the film Shiraz, shot in 1928, was made with the support of the Maharaja of Jaipur. The film’s opening titles announce that the film was shot on “real locations with no fake properties or sets.”

Still from the film Shiraz (1928). (Source: YouTube)

Krishna, in her paper titled “Princely Films: The Silver Jubilee Film of 1937 and the Princely State of Hyderabad”, suggests that “filming events was a part of producing the grandeur and greatness of the princely states which had audiences in Europe.” She added that films not only allowed for royalty in the princely states “to participate in discourses of modernity through the visual medium” but also helped them carve an image of themselves that merged modernity with tradition.

Still from the film Shiraz (1928). (Source: YouTube)

As princely states began losing resources and power, they were no longer in a position to invest in films or in artists. Loss of this feudal patronage had many artists, dancers and musicians seeking other forms of support for their livelihoods. Many began finding work in the Bombay film industry as extras, background dancers and junior artists. Krishna pondered the transformation of the artist, from being under patronage to being part of a film industry and the implications of this shift.

Goel’s research seems to, in some part, answer this question posed by Krishna. Her project focuses on the movement of Kathak dancers and choreographers to Bombay as a result of this dying patronage. She introduces us to Pandit Gauri Shankar, a Kathak dancer from the Jaipur gharana in Bikaner, Rajasthan, who moved to Bombay in the early 1930s. In Bombay, he began working with a woman called Leela Surkhi, who was better known as Madame Menaka, a half-Bengali, half-British dancer. Menaka did not come from a tawaif or traditional courtesan background and was introduced to Kathak by Indira Raje, the princess of Baroda, who was a friend of her father. Later, Pandit Gowri Shankar and Madame Menaka went on to tour Europe, where their performances were greatly appreciated and applauded.

Still of Gowri Shankar and Madame Menaka dancing (Source: menaka-archive.org)

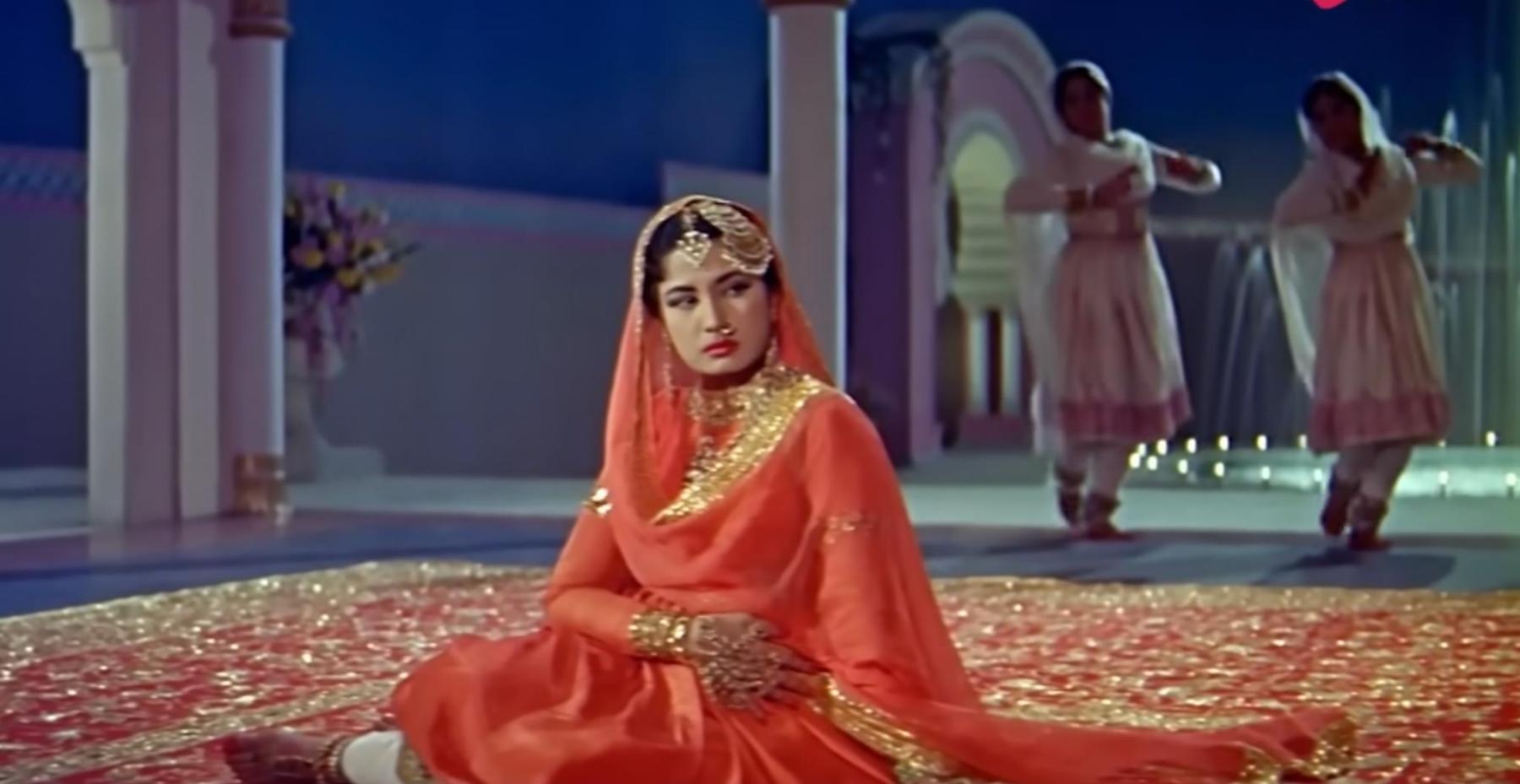

Gowri Shankar later went on to become a choreographer in one of the biggest productions of Bombay cinema: Pakeezah (1972). Goel’s focus shifts here to the background dancers who perform in the iconic and timeless “Chalte Chalte.” She was interested to know more about these Kathak dancers, trained by Shankar, who remain anonymous and uncredited.

After having hit a wall trying to investigate the names of the two dancers, Goel finally encounters character actor Anjana Mumtaz, a student of Shankar’s, who used to visit the sets of Pakeezah in her teens. She was unsure of their names and recalled the one on the right being Meenaxi and the other Sujatha, but she added that many dancers took on Hindu screen names to hide their Muslim identities. This artist migration from regions across India to Bombay goes undocumented as the dancers themselves remain uncredited.

Uncredited background dancers and Meena Kumari in the song "Chalte Chalte" from the film Pakeezah (1972)

In her book Dancing Bodies, Choreographing Corporeal Histories of Hindi Cinema (2020), Usha Iyer pushes Goel’s idea a step further by questioning why certain bodies are ‘silenced’ while others are given centrestage. She proposes that these background dancers need to be looked at in the larger context of a history of “silenced bodies of lower-caste women performers such as tawaifs (courtesans) and devadasis (temple, court, and salon dancers).” The cinematic treatment doled out to these dancers seems to draw from this gaze that predates film itself.

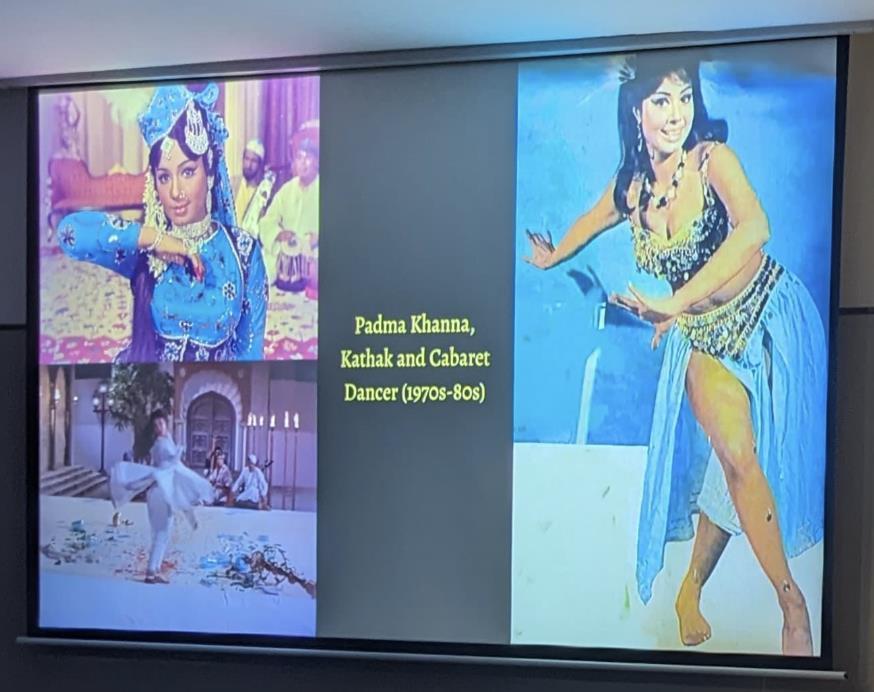

Image from Siddhi Goel's presentation of Padma Khanna, Kathak and Cabaret Dancer (Photo by Anoushka A Mathews)

As a Kathak dancer herself, Goel was curious to unravel this undocumented ecosystem of Kathak gurus who were training dancers that fed the film industry’s growing demand for background dancers, body doubles and dance assistants, seldom credited for their contribution and efforts. She uncovers some names that did manage to be credited, such as Kathak and cabaret dancer Padma Khanna, who was Meena Kumari's body double in Pakeezah and whose bloody feet filled in for Meena Kumari in the final dance number, “Teer-e-nazar dekhenge.”

Shot of Padma Khanna’s legs as Meena Kumari's body double from the film Pakeezah (Source: YouTube)

Goel’s presentation helped draw a connection between how the lack of credited labour is reflected in the visual treatment of the background dancers—out of focus, individuality glossed over by group movements and lending limbs for iconic shots that render them not only faceless but nameless. Krishna’s documentation of the visual cultures of princely states helped understand how the absence of these stories in the archives limits the boundaries within which we view the history of cinema in India.

To learn more about IFA’s event Past Forward, read Vishal George’s reflections on questions of craft and community in Ashok Maridas’ Casting Music (2016) and Lokesh Ghai and Jaymin Modi’s The Last Shoemakers of the Doon Valley (2024) as well as Aditi Maddali’s Songs of Our Soil (2019).