On Ghosts in Machines: Responses to a Present Devouring Itself

By beginning Desert Notes: Reflections in the Eye of a Raven with the lines: “I know you are tired. I am tired too. Will you walk along the edge of the desert with me?”, Barry Lopez indicated to readers that time would move differently and engage the senses differently, through his pace and tone—sparse and, then, suddenly laden—in the desert he was constructing. The exhibition Ghosts in Machines, curated by Damian Christinger at the Serendipity Arts Festival 2024, displays a similar sensitivity to the vocabularies and syntaxes of ecological time across a range of creative practices, including photography, archives, video and sound installations.

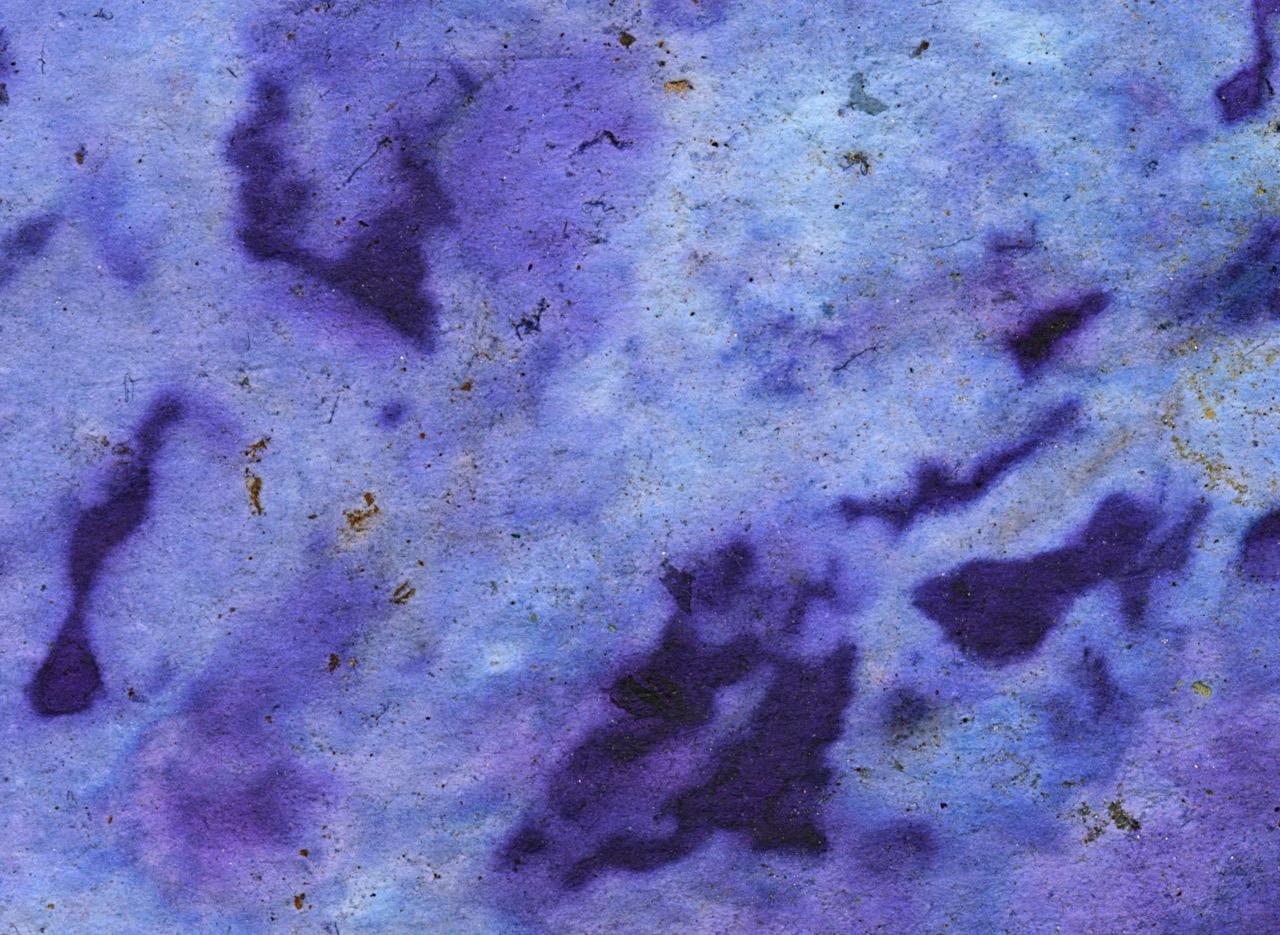

From the series Elemental Whispers by Anuja Dasgupta (2022-present. Anthotype with sunlight, river drift and sittings by birds, cattle and insects. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Ravi Agarwal’s video work The Power Plant serves as a starting point for visitors, setting the context using a disembodied voiceover—possibly a monologue of the abandoned power plant itself—sharing its nostalgia for the hopes and aspirations once tied to modernisation and the industrial complex, as well as for the hum of its machines that now lie disused. For Christinger, the persisting troubles and failures of modernisation and colonialism serve as the ‘ghosts’ in the machinery of contemporary cultural production, continuing to perpetuate ideas such as a separation between humankind and nature, resulting in a plethora of present-day disasters including climate crises and unstable economic systems. Ghosts in Machines investigates how these troubles persist in contemporary cultural and creative production, offering departures from myopic, extractive ways of thinking and making.

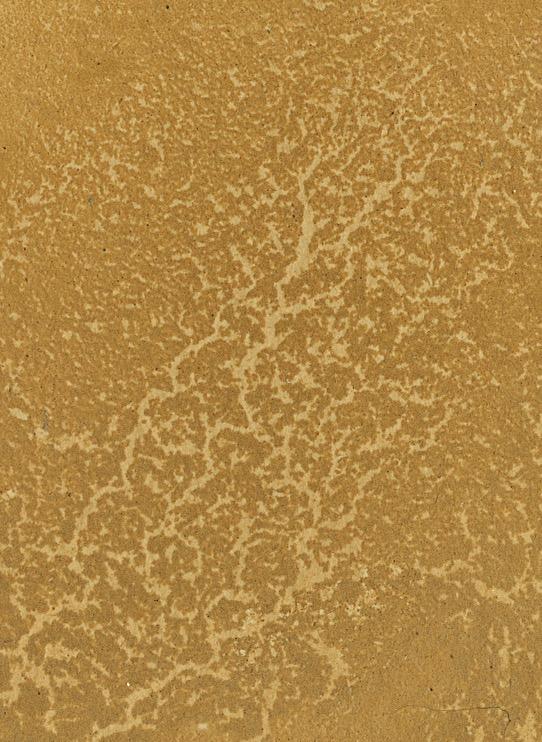

Still from Frequencies of the Forest by Radhika Agarwala (2024. Video and sound installation. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Another spectre of the past that persists in the present is the dominant notion of time as ‘clock time’, with fixed hours and seconds, even and equal across spaces, eternally moving forward. The artist and geographer Trevor Paglen notes, "Before the railroads, each place kept its own time. (…) The creation of absolute time entailed the subjugation of localities, regions and nations to a centralized tick of a clock at the Royal Observatory in south London: Greenwich Mean Time”, in the interest of greater productivity and uniformity in the age of industrialisation. The works of artists like Anuja Dasgupta and Radhika Agarwala attempt to dismantle this absolute time, exploring lost sensibilities of timekeeping and alternative kinds of time and narratives that may be distinctive to their local environments.

The exhibition features forty-four anthotype prints created in Ladakh that are part of Dasgupta’s body of work titled Elemental Whispers (2022–ongoing). In these works, insects, plants, cattle and river drift create ‘self-portraits’ at their own pace, moving and resting on plant emulsions coated onto cotton paper and left to develop by riverbanks. The resulting anthotypes give the sense of a landscape gradually gathered together by multiple creatures and elements. Each part of this process is carefully considered in dialogue with the environment: the paper is made of cotton, to dissipate fully in case blown into the river; sheets are left out for days, not surveilled, with the artist only visiting the work, so as to not disturb its creation by different creatures. Plants with which to make emulsions are foraged for, in their specific seasons, with the help of the artist’s friends. In these ways, Dasgupta seeks out time not as a tool to measure her productivity, but rather as a potential mode of understanding the pace of her surroundings in Ladakh.

From the series Elemental Whispers by Anuja Dasgupta (2022-present. Anthotype with sunlight, river drift and sittings by birds, cattle and insects. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Several aspects of this practice indicate a departure from the spectre of human or clock time and an approach in which human presence and desire are not centred. These include the impulse to surrender control of the composition of the images, the ephemerality of the photographs as they are prone to fading over time with exposure to light and the anonymity of the mark-making on the paper, where viewers, including Dasgupta, can only guess at what is river drift and what is an insect. Dasgupta describes her move away from traditionally composed or representative photo-making towards images articulated differently—by the ‘subjects’ themselves—as an “embracing of time.” “The desire for permanence”, Dasgupta reflects, “to create, build things that will last forever—this seems to be the root of most of the crises that we are facing right now, both environmentally and politically.” Responding to the uncertainties produced by climate crises, the artist argues that the sensibilities and methodologies of our disciplines cannot afford to remain stagnant: “If nothing will last forever, why should I try to make art that will?”

From the series Elemental Whispers by Anuja Dasgupta (2022-present. Anthotype with sunlight, river drift and sittings by birds, cattle and insects. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Dasgupta’s anthotype process calls to mind anthropologist Tim Ingold’s discussion on weaving as a craft practised by both humans and birds:

“The conventional notion that the birds’ activity is due to instinct whereas humans follow the dictates of culture is clearly inadequate. (…) In both cases, it is the pattern of regular movement, not the idea, that generates the form. And the fluency and dexterity of this movement is a function of skills that are developmentally incorporated into the modus operandi of the body—whether avian or human—through practice and experience in an environment.”

The question of instability, collapse and change are also taken up by Radhika Agarwala’s immersive video and sound installation, Frequencies of the Forest (2024). Located in a small, dark room, smelling of fresh rain, the work responds to the number of people present. With one or two viewers in the room, the experience is that of peaceful sounds like flowing water and birdsong. However, a crowd of viewers activates pandemonium and the rapid disintegration of the forest, creating an inferno with a blistering soundscape. Like Dasgupta, Agarwala too resists the traditional, human narrative, ceding to a kind of omniscient narrator, produced by frames layered with drawings, cyanotypes, photographs and video footage, and the immediately sensorial leaves, mushrooms, stones and soil that visitors step into. The installation tells the story of a kind of cursed relationship, with Agarwala noting that, “whenever there is an absence of humans in nature, nature thrives.” The site of the ruin, which runs through much of Agarwala’s works, presents a series of paradoxes—as a testament to decay as well as survival, a presence growing despite neglect—that are echoed in Ravi Agarwal’s Power Plant. Both video installations unsettle notions of comfortable, linear, forward-moving time, putting forth a voice from the past that never leaves and moves unpredictably, as it pleases. As Brian Dillon writes in “A Short History of Decay”, “the ruin is a fragment with a future; it will live on after us despite the fact that it reminds us too of a lost wholeness or perfection.”

Still from Frequencies of the Forest by Radhika Agarwala (2024. Video and sound installation. Image courtesy of the artist.)

The exhibition also features the dystopian animations of Swiss artist Yves Netzhammer, which look at the interactions between the human and more-than-human in nightmarish, strange scenarios, questioning what forms the peripheries of bodies; Herbert Weber’s photographs exploring how a body interrupts a landscape; Sonia Mehra Chawla works with archives from England and India to study how jute production has shaped manufacturing facilities and migrations in India in both the past and present; as well as a video installation and soundscape symphony by Marianne Halter and Mario Marchisella, titled Opera of Trade and Commerce, where a symphony of plastic tape that is pulled and torn grows increasingly panicked and aggressive as packages accumulate and move across sites of business.

Ghosts in Machines offers multiple interpretations and imaginations for a future arrived at by stumbling over the past. Engaging closely with the artists’ localities, shared histories, and speculations for the future, the works present an idea of the personal that is not confessional or autobiographical, but rather the personal as connection—an approach that destabilises the imagined categories of ‘human’ and ‘nature.’

To learn more about the previous edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival, revisit Annalisa Mansukhani's interview with Ravi Agarwal on the show Time as a Mother, co-curated with Damian Christinger, Arundhati Chauhan's interview with curator Veeranganakumari Solanki on the exhibition Synaesthetic Notations and an In Person walkthrough of the show HOLY FLUX! by members of The Packet.