On Documenting Conflict: Unseen Acts at the Another Lens Symposium

Ashish Rajadhyaksha introduces the panellists of “Unseen Acts” as part of the Another Lens Symposium. (IIC New Delhi, 30 November 2024. Image courtesy of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.)

On 30 November 2024, a symposium at the India International Centre, New Delhi, celebrated the launch of the volume Another Lens: Photography and the Emergence of Image Culture (2024) edited by Rahaab Allana, the fourth installment in the series India Since the 90s presented by Tulika Books and edited by Ashish Rajadhyaksha. In considering the decade of the nineties, which saw many watershed events that have had a lasting legacy on the socio-political fabric of India, the series aims to deploy a reflective understanding of the past through the lens of the present. The book contains an assemblage of previously published essays, which are presented in conversation with one another to examine the role of photography and moving images in documenting the transitional period of the nineties.

Posters dot side of the highway. (Still from Lanka: The Other Side of War and Peace. Iffat Fatima. 2005. Image courtesy of the artist.)

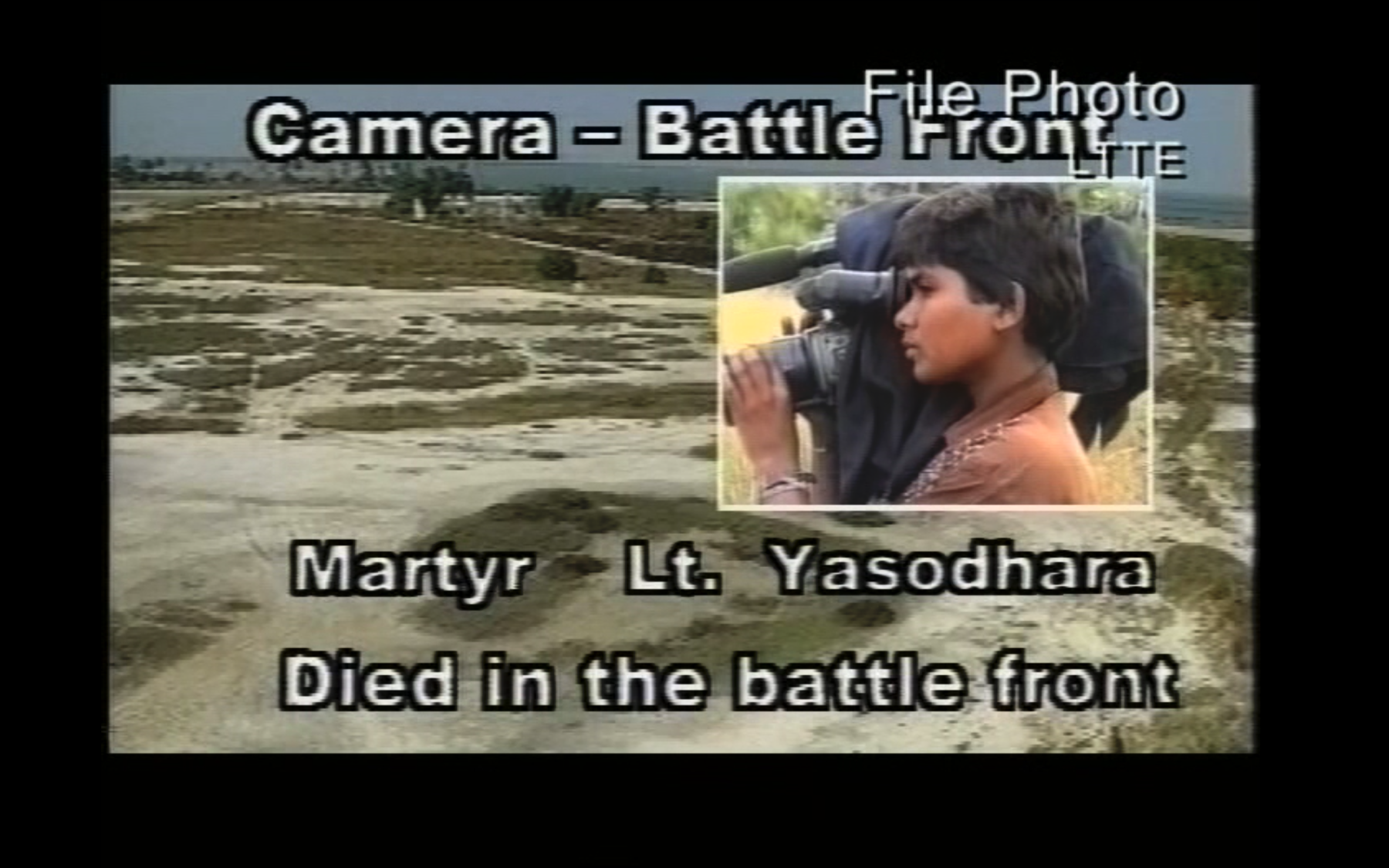

The first panel of the day-long symposium was titled “Unseen Acts” and comprised artists Sheba Chhachhi, Iffat Fatima and Ishan Tankha, with the session moderated by Ashish Rajadhyaksha. Taking as a point of commonality their preoccupation with sites of conflict, the panel sought to reflect on the nature of witnessing, the place of documentary and the possibilities of community. Iffat Fatima’s film Lanka: The Other Side of War and Peace (2005) traverses across the A-9 highway in Sri Lanka in the brief interim afforded by the ceasefire between the Sinhalese state and the LTTE. The highway cuts across the country from north to south and had been completely closed and barricaded during the war. Filming the journey across the reopened highway, the remnants of war are inescapable. Posters promoting recruitment and shrines to those who were martyred filled the countryside. In the discussion, the filmmaker spoke about how the highway has been renovated in the aftermath of Sinhalese victory, resulting in the erasure of any material signs of the long-fought civil war. The film is also interspersed with archival footage shot by LTTE cadres documenting the war in order to bring awareness and support for their cause. The fighters at the frontlines capturing the war with their cameras knew that it was a suicide mission and the videos are essentially memorial videos that are circulated depicting the martyrs.

The place of photography as memorial and forms of remembrance also finds echoes in Fatima’s work in Kashmir, especially in the film Khoon Diy Baraav (Blood Leaves a Trail, 2012). Here, the filmmaker chronicles the large number of enforced disappearances in Kashmir and the work of the Association of Parents of Disappeared Persons in their quest for justice.

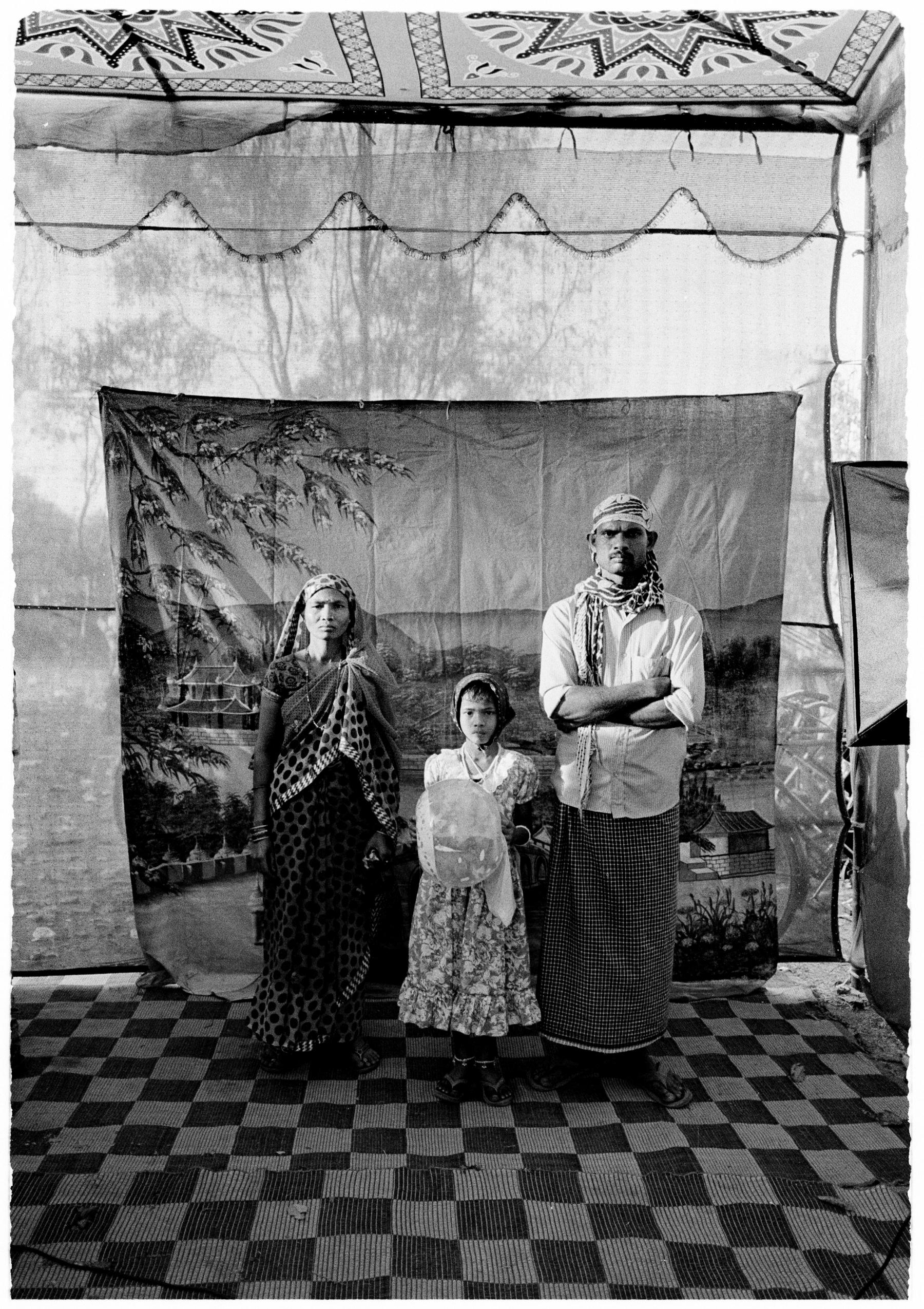

Shahjahan Apa – Staged Portrait, Nangloi, Delhi 1991. (Sheba Chhachhi. From the series Seven Lives and a Dream, 1980–91. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Intertwining art and activism, Sheba Chhacchi’s practice documents the women’s movement against dowry in the 1908s and 1990s. In reflecting on the process of photographing demonstrations and campaigns against gendered forms of violence, Chhachhi traces her journey of negotiation with the documentary image as she moves towards staged portraits. Dissatisfied with the documentary form’s association with an evidential claim, the staged portraits were made in a collaborative mode, which allowed for the women being photographed to decide how they wished to be represented. Here, the ‘truth’ claim of photography is complicated by foregrounding the subjective and constructed nature of the photograph. Chhachhi highlighted the composite nature of images as a way of resisting a unified meaning and noted that many of the portraits of the women included a photograph as well, gesturing toward the possibility of many layers to the archive. This has influenced her approach and process as she has recently been working on making her archive available to the larger public.

.jpg)

A Maoist guerilla repacks her bag containing letters from home, photographs of a sister, medicines and ammunition before leaving camp. (Ishan Tankha. From the series A Peal of Spring Thunder. Abujhmaad, Chhattisgarh-Maharashtra Border, 2007–16. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Ishan Tankha’s photoseries A Peal of Spring Thunder (2007–16) documents the lives of Naxals in Chhattisgarh, with the intention to question many of the preconceived notions that existed about the Maoist movement. Questions of power and hierarchy remained in his mind as he saw another photojournalist take a photograph such that the barrels of the guerilla fighters’ guns pointed towards the camera. While the photograph was staged with the participation of the fighters, the narrative that is created or circulated contributes to a certain kind of image of Naxalites. The project began as part of his job as a photojournalist but the artist sought to return to the site and do a longue durée study. Tankha spoke about how journalists are expected to focus on or privilege great, spectacular moments. Instead, by returning to Chhattisgarh again and again, the artist wanted to capture the quotidian. Thus, in his work, Tankha considered other objects that the fighters carried—whether it was toothpaste or photographs of family—in order to counter a certain prejudiced imagination of who the fighters were.

Ashish Rajadhyaksha, Sheba Chhachhi, Iffat Fatima and Ishan Tankha at the “Unseen Acts” panel as part of the Another Lens Symposium. (IIC New Delhi, 30 November 2024. Image courtesy of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.)

Opening the discussion, Rajadhyaksha was particularly interested in the idea of the afterlife of images and how they take on different readings and meanings. Taking Ariella Azoulay’s The Civil Contract of Photography (2008) as a reference, he invited the panelists to speculate on ways in which the meanings of images may be constructed and the ways in which it is possible for agency to rest with those being photographed. Responding to the multiple meanings contained within a photograph and the potential for agency, Fatima referenced a Boston Review article by Azoulay in which the author writes about images of the Palestianian genocide that are being circulated by Israel as proof of the defeat of Hamas. While the narrative being put forth is one of victory, inscribed within the photograph is the large-scale violence and history of brutalisation by Israel that existed prior to 7 October 2023. Chhachhi spoke about how Israeli soldiers are determined to destroy all photographs, passports and forms of identification that they found in an attempt to further erase documents that indicated Palestinian existence. She used this example to speak about how we must acknowledge that archives exist through a process of exclusion where forms of authority determine what is to be remembered and preserved.

The images explore the relationship between social and physical environments and focus on ecological degradation, political violence and the corresponding displacement and dispossession of indigenous communities. (Ishan Tankha. From the series A Peal of Spring Thunder. Chhattisgarh, 2007–16. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Speaking to questions of ethics and agency, Tankha acknowledged the power equation that existed as he entered Chhattisgarh as a photographer from the city, with a certain amount of privilege. He pointed out that the kinds of images he took would probably only be circulated in niche circles—distributed among like-minded people or NGOs, and spoke about how meaning is often determined by context. In an anecdote, he recalled an incident where, upon visiting the area, lawyers who had previously been welcoming suddenly became cold. When he asked them what was wrong, they showed him an article in a magazine that represented the Naxals in an unsympathetic light, which had been accompanied by Tankha's photographs. As a photojournalist working for a paper, the rights to the images belonged to the paper and the intent with which they were shot was of little consequence to the publishers. Photographers and artists have to navigate these power dynamics when the image takes on a life of its own through forms of circulation.

Cinematographers martyred for the cause feature in LTTE archival videos (Still from Lanka: The Other Side of War and Peace (Iffat Fatima. 2005. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Reflecting on the role of communities and photography, Fatima spoke about the videos made by the LTTE fighters and the idea of community that was addressed in such videos, since they served not only as memorials but also as calls to recruitment. The director has copies of these videos as part of her archive, which she is keen to make accessible or share with an institution so that this history is not forgotten or erased. In the context of Kashmir, Fatima referenced the double role played by photography. On the one hand, photographs served as the last traces of the disappeared persons; while on the other, photography in the form of surveillance cameras led to the identification and persecution of people in the region. For the people who gathered to raise questions about victims of enforced disappearances to be able to come together as a community permitted a space for the expression of grievances. The possibility of standing together and sharing in their grief allowed for a degree of reparation. Yet many of these people did not wish to be interviewed for the film as they felt that the agency of the camera was elsewhere and could very easily be used against them.

Raising a point of departure from Azoulay’s understanding of community, Chhachhi pointed out the temporariness of such communities. She believes that while such communities can exist at the time of the making of the photograph, communities created in the shared reading of the photograph remain temporary. Moreover, community is a politically charged term, and Chhacchi urged that it be used with discretion.

As each of the works being spoken about bore witness to a certain moment in time, they remind us of the close intersection between aesthetics, ethics and politics as well as the urgent role that artists play in documenting and representing conflict in order to combat erasure.

To learn more about other artists working with representations of conflict, read Najrin Islam’s curated album from Moonis Ahmed Shah’s Telegrams to Bollywood from a Mad Landscape Scout (2018) and her essay on his series Gul-e-Curfew (2021) and Sukanya Deb’s essay on Rohit Saha’s photobook 1528 (2017) which examines the Malom massacre in Manipur.