The Measure of Value: Daughter of the Sea

“ I followed her into the sea. But after inhaling the water, I was fighting to live.”

Screened at the 9th edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival held in Goa from 15-22 December 2024, Nicole Gormley and Nancy Kwon’s 18-minute documentary Daughter of the Sea: Sisterhood in the Sea (2023) is a deeply moving and intimate account of the alienation caused by capital’s imperative of competition and the individualistic parameters of productivity that constitute success. The film reflects on the lives of labour that produce what is considered to be of value, the necessity of community and shared purpose as crucial to well-being, and our relationship with nature as fundamental to human life.

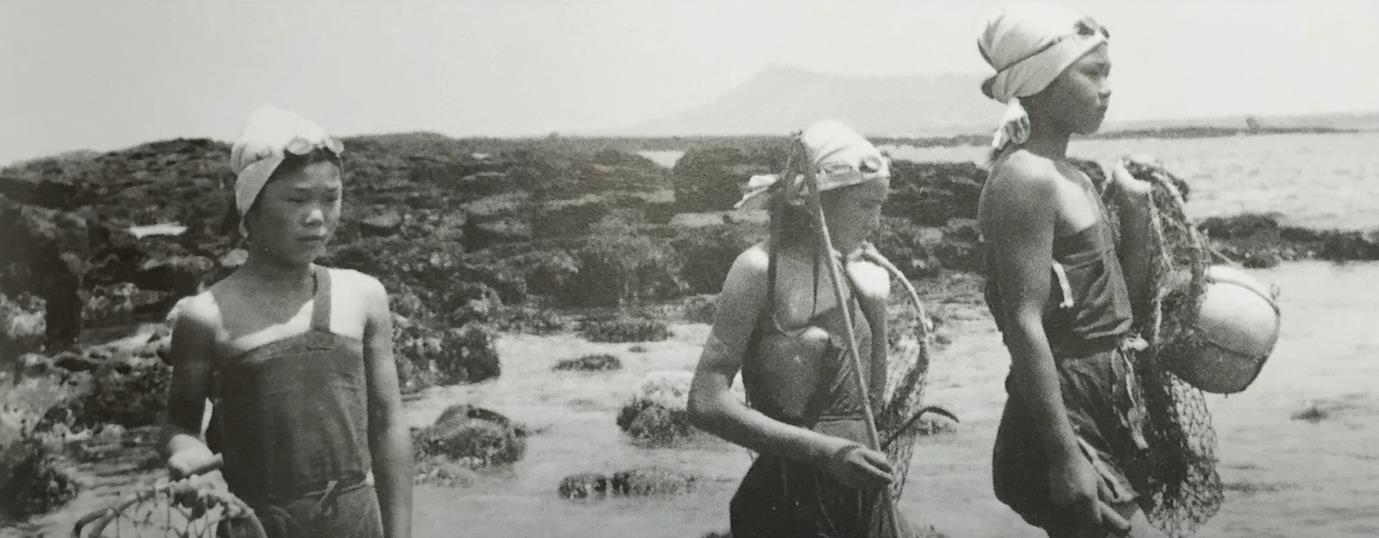

Jaeyoun Kim is the sixth generation of a family of haenyeos, or women of the sea—female divers in South Korea’s Jeju province who harvest seafood from the ocean. Even though life on Mara Island depends on the haenyeos as financial providers as they collect abalone shells and conches which have high value, the life of a haenyeo is difficult and they are sometimes ashamed of the work. The community has now dwindled considerably, with a majority of haenyeos being above sixty years old.

Kim’s mother and grandmother too discouraged her and her siblings from continuing the family tradition. The first in her family to graduate from college, Kim finds a lucrative job as a banker in Seoul. Yet, despite having a loving partner and children, she finds that her life is against her nature and feels that the only way to experience peaceful sleep is to die.

“It was like going to battle, instead of living… Each day was such a pain to endure… If I opened my eyes in the morning, I hoped it was a dream.”

Worried about her health, her aunt asks her to join her in the sea. Kim first considers this an opportunity for suicide. But she is taken aback by her bodily response:

“My mind wanted to die, but my arms and legs were constantly moving.”

Dumbfounded, she returns home. Tired after following the other haenyeos in their work, she has a new, unfamiliar desire—a desire to wake up and go back to the sea the next morning. Mirroring Kim’s internal world, where she gathers the sea of her emotions; the immersive underwater cinematography reminds us not only of the ebb and flow of turbulent waters but also of the rich life that is often hidden just beneath. The film is then also an ode to the process of finding the courage to discover that possible world of contemplation, healing and purpose.

“When we go into the sea, the first thing we do is to take a deep breath. That sound is called sumbisori and it sounds like a whistle… When we work, we hold our breath… but in a way, it’s also a space where I can breathe.”

If this space to breathe, to keep aside one’s worries and troubles for a while and remain content in the present is deeply personal, what Kim emphasises is the ways in which it is a sense of community that enables this journey.

Not only did she receive support from her family members in her decision to become a haenyeo, but while other jobs focus on one’s abilities, she says, for haenyeos, they are all considered haenyeos with the same regard, irrespective of the quantity or quality of their individual output. What binds them is their love for the work.

Sitting down to dinner after a hard day’s work and going over family albums, Kim points to a photograph to ponder over how her grandmother continued to dive until she was ninety-five-years old. She hears from her aunt, now sixty-nine-years old, that she would work until her heart kept beating. In a moment of realisation that might be crucial for our understanding of an individual’s intrinsic value as untethered to productivity, of alienation from one’s self in contemporary capitalism as a key determinant of mental illness, of shared purpose and community as fulfilling aspects of an enriching life, and of one’s connection to nature as a source of healing and growth, Kim reflects:

“I was meant to be a haenyeo. So that was my purpose, but instead of going into the water, I kept doing other work. So I got mentally sick. I had no choice but to go into the sea.”

To learn more about programmes at the 9th edition of the Serendipity Arts Festival, watch an interview with Dayananda Nagaraju and Niranjan NB as they speak about their project The Everlasting River (2024) and watch a walkthrough by Ravi Agarwal and David Verghese of the exhibition Carbon (2024). Also read Anoushka Antonnette Mathews’ review of Niharika Popli’s If I Could Tell You (2024) and Aparna Chivukula’s essay on the show Ghosts in Machines (2024) curated by Damian Christinger.

All images are stills from Daughter of the Sea: Sisterhood in the Sea (2023) by Nicole Gormley and Nancy Kwon. Image courtesy of the directors.