Frissons of a Novel Kind: The Sher-Gil Family Archive

“Pleasures are like photographs: in the presence of the person we love, we take only negatives, which we develop later, at home, when we have at our disposal once more our inner darkroom, the door of which it is strictly forbidden to open while others are present.”

—Marcel Proust, In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower.

The publication of the first volume of Proust’s seminal work A la Récherche du Temps Perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913) coincided with the birth of the doyenne of Indian modernism, Amrita Sher-Gil. In her tragically short, yet momentous lifetime, Amrita was not just a prolific painter, but also a voracious reader (repeated requests to send over particular volumes of Proust populate her letters to her sister and father from 1938 to the end of her life; 1941), writer and the subject of her father, Umrao Singh Sher-Gil’s extensive photographic pursuits. She went on to read the French writer in 1938, at the age of twenty-five. In a letter to her art historian friend (later biographer) Karl Khandalavala, Amrita notes the profound first impressions of reading Proust, highlighting a state of “complete though receptive void”—a prerequisite for reading, enjoying or even creating any work of art. She rejects the romanticised image of the struggling artist and declares had she been in love or in the midst of a financial crisis, she would not be able to paint.

What are the newfound pleasures of photography? What is the nature of the delay which Proust presents? Can it be understood in the “receptive void” proposed by Amrita? Through this essay, I wish to delve into the ongoing exhibition A Hungarian-Indian Family of Artists: Master and Disciple at Jaipur House, the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA), on view from 31 January–31 March 2025, and discuss the depiction of leisure in the vast photographic archives of the Sher-Gil family presented here. Since photographs were frequently shared with family members based in Hungary, most of the photographs (taken by Umrao Sher-Gil) are from the Ervin Baktay estate housed at Hopp Museum, Hungary, which presents an interesting history of the circulation of diverse photographs within intimate circles. Furthermore, Amrita’s “receptive void,” along with Proust’s analogy of photographs as pleasures, is pivotal in my understanding of the art of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil’s ‘amateur,’ domestic yet mobile photography in the initial decades of the twentieth century.

Much ink has been spilt on the nature of the gaze in Umrao Singh Sher-Gil’s photographic self-portraits—intimate, sensual, whimsical, intense and powerful. It is often remarked with considerable surprise that he never wrote on his photographic practice (although he was an avid reader of the latest developments in the field). In this essay, I wish to draw attention to the other kind of ink which he spilt on photographs, quite literally by inscribing most of them, revealing the duality of the medium he used for his vast array of self-images.

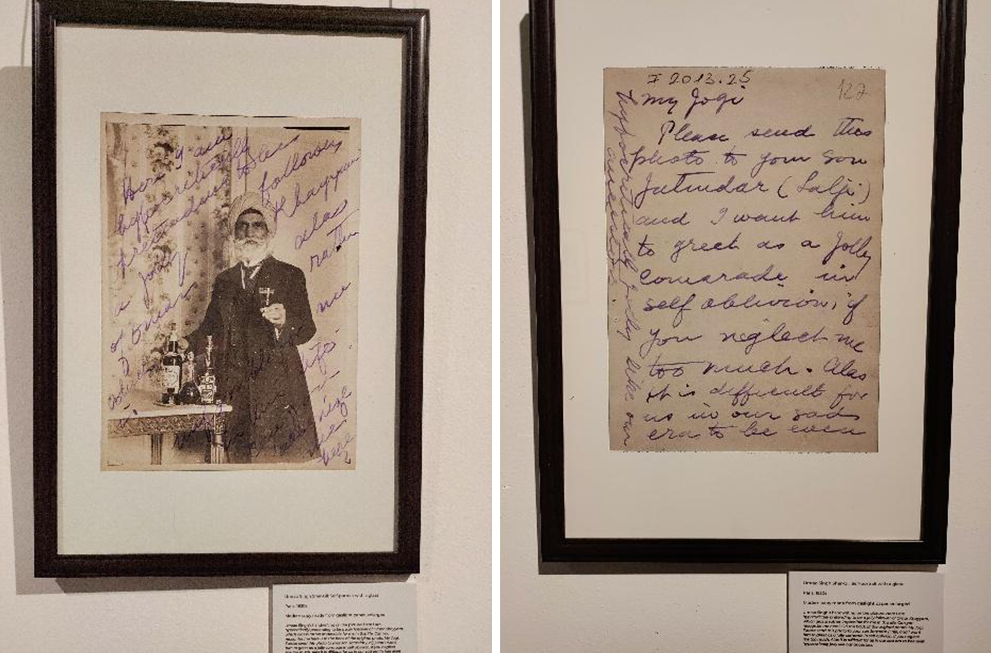

Self-portrait with a glass. (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Paris, 1930s. Modern copy made from gaslight paper. Photographed by author.)

Holding a goblet of wine in his raised hand, with eyes shining bright with humour and a smirk, Sher-Gil looks on as sentences in tilted rows frame his body, voicing the silent humour initiated by the image. In this photo-letter to Jogi (his close associate, Sir Joginder Singh), he mentions that this is his attempt to hypocritically pretend to be a “jolly follower of Omar Khayyam,” ending with a rhetorical question—“Can you recognise me here?”

The photograph above is one of the many examples of the composite body of the photo-letter—a photograph inscribed with an entire letter (front and back!). It makes the twin ontological layers of the photograph apparent—not just the image represented but also the material body of the photo object. In this case, the image is almost obscured by the textual inscription on its material body. And an object like this—meant solely for circulation, not merely record-keeping (noting the date, place, person, etc.)—opens up an uncharted terrain of the mobile photograph as not just memorabilia, but also as a carrier of multimedia messages. More such examples in Umrao Singh Sher-Gil: His Misery and His Manuscript confirm that this practice moves beyond mere ‘captioning’ or attaching images to letters, but rather the self-portrait inscribed with the handwritten note produces a complex, distinctive, ‘speaking’ image. The fading legibility of Sher-Gil’s handwriting fuses with the clarity of the staged self-portrait to subvert the very ambitions of the medium as a serious document.

Significantly, this allows one to grasp the playful nature of Sher-Gil’s amateur photography and theatre, also manifested in the larger work of early pictorialist photographers during this period, especially in erstwhile Bombay. In theatre, the actor can never view themselves in character; however, photographs like these elicit frissons of a novel kind. Are these the pleasures that Proust associates with a photograph? In its widespread production and circulation within family albums, photography became the art of play—subjecting memory, re-cognition, performance and leisure to modern ends. The numerous Sher-Gil photographs of fancy dress parties across Paris and Shimla during the interwar years testify to this well-established practice among certain elite social circles to prepare to dress for a party (and/or an amateur play) with the deliberate intention to be photographed. Naturally, the Sher-Gil sisters became adept at the art of posing for the camera from childhood.

L: A costumed tableau vivant of Omar Khayyam. Amrita and Indira at the feet of Umrao Singh. (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Shimla, 24 December 1928. Modern copy from gelatin silver. HFA_ F.2013.18. Hopp Museum, Hungary.)

R: Listening to Music in the Drawing Room. (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Shimla, February 1923. Modern copy made from gaslight paper, HFA_ Ad. 5756.10.30.1. Hopp Museum, Hungary.)

The image above (left) depicts Umrao Sher-Gil seated in a complete enactment of Omar Khayyam, surrounded by four young costumed women—including his teenage daughters as they flank his feet. The image on the right goes further back in time, showing the two young girls draped in a decidedly ‘oriental’ attire, listening to music with their mother, Marie-Antoinette. Her handwritten Hungarian inscription on the verso addresses the image to Marie’s brother Ervin. The close attention to detail in the costuming of each figure as well as the placement of props reveals a well-oiled paraphernalia at work in producing these intricate, intertextual tableaux.

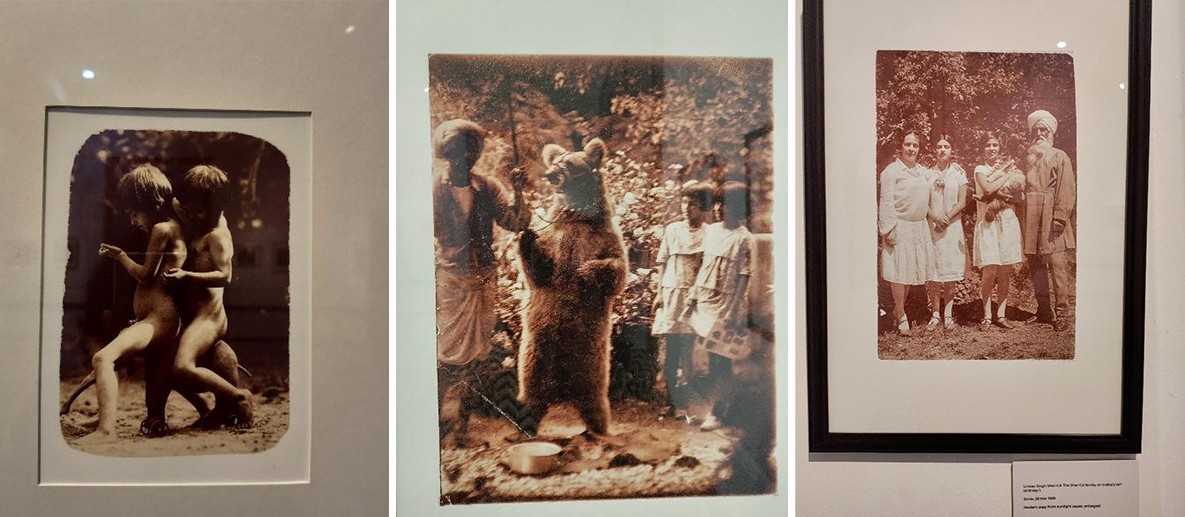

L to R: Amrita and Indira on toy elephant. (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Gottesman House, Dunaharaszti, Hungary, c. 1917. The Estate of Umrao Singh Sher-Gil & Photoink. Photographed by author.) Indira, Amrita and the Bear Dancer. (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Shimla, c. 1925. Modern copy made from gelatin sun print paper. Photographed by author.) The Sher-Gil family on Indira's fourteenth birthday. (Umrao Singh Sher-Gil. Shimla, March 1928. Modern copy from sunlight paper. Photographed by author.)

Even as technology began to take centre stage in the experience of human leisure, the premodern sites were not immediately blotted out of memory and practice. The three images above suggest the fascinating range of animal presence in children’s play, entertainment and companionship. The first one, strikingly reminiscent of American photographer Sally Mann’s controversial series Immediate Family (1990), shows two lean kids, unclad and barefoot, sitting atop an elephant toy cart—a model which has been consistently popular among children across historic civilisations. In the second image, the two sisters are immersed in viewing a bear dance in close proximity. In verso, their mother writes in Hungarian, “Bear dancer is coming to the house!” which at once expresses the delight and the distress caused by this entrance. Lastly, the third image above depicts one of the many cats in the Sher-Gil photographs; the most popular was Marie’s dearest Bubu, whose disappearance, mentioned in Amrita’s letters, seems to be an unsettling event in the family. Amrita even finds a ‘replacement’ cat, which she assures would be as good as Bubu. The prints displayed in the exhibition do suggest that the Sher-Gils had a preference for feline companions, not discrediting the presence of other canine comrades.

In each of these images, the locus of pleasure is quite distinct. The only commonality that brings them together is their entry as favoured subjects into the new, leisurely terrains of photography. There is something intensely important about photographing yourself, your kids playing, engrossed in watching an unusual sight, and even holding pet animals close to their heart. It is not just a permanent marker of memories or ways of holding captive the time that passes by swiftly, seeing children grow up. It functions as an instrument of prolonging the instantaneous pleasure located across these sites of leisure. The delay between the occurrence and experience of pleasure, noted by Proust, is mirrored in the act of photographing and viewing the positive image. Thus, the inscription seems to be produced at this delayed moment of reception, which triggers certain elements around the somewhat hazy initial moment of photographing a scene. Art critic Aveek Sen in “Bedtime Stories” writes of a sleep-induced state as a result of deep engagement with masterpieces of music, cinema and literature. This wakefulness activated by sleep is comparable to Amrita’s “receptive void” as well as Proust’s delayed pleasures in the form of photography’s deathly stillness. These moments of quotidian bliss in the Sher-Gil family become markers of such sleepwalking encounters in the intertwined histories of modern leisure and colonial photography.

To learn more about explorations of leisure, read Anisha Baid’s essay on Homai Vyrawalla’s photographs of early women’s colleges in India, Arushi Vats’ essay on Juju Bhai Dhakhwa and Najrin Islam’s reflections on Indu Antony’s feminist practice.