Fragments of Memory at the Chennai Photo Biennale

Given the crucial role photography plays as an aid for memory, it raises important questions about our engagement with the past, present and future. Artists at the Chennai Photo Biennale reflect on the ways in which memory and meaning in their practice are influenced by time and space. Looking back at his more than two decade-long preoccupation with architecture in India, Sebastian Cortés observes how time and memory are embedded in the spaces he photographs in his retrospective Time Present Time Past. Manisha Gera Baswani speaks about the act of looking back and engaging with her own archive over the last twenty-five years in Artist Through the Lens. Vivek Mariappan’s series As close as it gets captures the feeling of the familiar made unfamiliar as he returns to his hometown to document it. Alina Tiphagne ruminates on the liminal space occupied by autobiography in The Liturgy of the Lost Bird. Fotohane Darkroom works with local and migrant children in south eastern Turkey to develop storytelling as a medium of expression to document their lives, which have been exhibited as the series Stories in Shadows. Steevez provides an intimate glimpse into his relationship with his father through the photobook Last Seen 24 Sep 2015.

From the series Time Present, Time Past. (Sebastian Cortés. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Mallika Visvanathan (MV): Since Time Present Time Past presents a retrospective of your work, I was curious about how, as an artist, you revisited your work and presented it in the form of an exhibition. When you were framing these images, how were you thinking about memory and the time that is imbued within the spaces?

Sebastian Cortés: There are three separate projects included in Time Present Time Past, but they all form a part of my observations on heritage and the concept of memory embedded within spaces and how it ties into a logic of a consciousness of the past. This has been the central theme in my practice for the past twenty years. If one were to look at it chronologically, it began with Puducherry in 2004. In collaboration with INTACH, my project sought to explore the living reality of India’s colonial heritage. While it was more documentary-like, I managed to create an artistic interpretation of the location to underscore what was a transformative moment—from being an abandoned location in South India to its rebirth as a heritage haven. There is a unique blend of French and Tamil influences; the spaces point to a peaceful coexistence despite visual differences between the two cultures.

-1280x9601.jpg)

From the series Time Present, Time Past. (Sebastian Cortés. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Sidhpur, which is where the second project was located, is a rich merchant's expression of international connections. The community of Bora merchants here had trade links with North Africa and Europe. Their homes illustrated the influences of these other cultures. There was an atmosphere or an open feeling of trying to be European, Muslim and localised simultaneously. This again underscores the fact that the colonial influences go both ways, that colonialism was imposed but also absorbed by people travelling. Over time, Sidhpur became a forgotten corner as commerce shifted, and that part of Gujarat no longer fell on trade routes. So most of the homes had been abandoned when I went there. But through my work and exhibitions at various museums, people have seen it and heard about it and it has now become a heritage tourist destination.

The third project focused on the homes in Chettinad. Many members of the Chettiar community were traders, who built enormous palatial homes as a statement of their success. They brought in marble from Italy, wood from Burma, tiles from Japan, lighting from Venice, etc. These houses were an incredible feat of architecture, craftsmanship and vision, which is rare to find anywhere else in the world. They are a melting pot of influences, but done in an elegant and constructive way. They are not comfortable homes but temples to wealth, success and family.

-1280x960.jpg)

From the series Time Present, Time Past. (Sebastian Cortés. Image courtesy of the artist.)

When it came to photographing these spaces, my approach was very direct. When we look at its etymology, photography is “writing with light.” The act of writing is already an act of memory because the moment you put words down, they are already in the past. So photography, by its nature, is already the past. But it has an immediacy and also a lingering quality to it. My work is an act of recording the past. I am not trying to elaborate on any future image. I am using an aesthetic palette to record stones, and these stones outlive the people. I have found that the stones tell stories of the past, but at the same time, they can alter the future. As I mentioned before, the more exposure that the photography gave to these places, the more it became an active functioning process for the future, because it came to be seen as heritage. This developed into heritage tourism, which produced money and then opened other possibilities for the future. I am out to create a feeling of curiosity, of well-being and a sense of what architecture is. Architecture is an envelope that surrounds you. The home is the first place that you encounter, the womb of first thought. And I try to give that sense of the womb with all its ornate qualities.

Anjum Singh installing her solo 'all that glitters is litter’ at Vadehra Gallery. (Manisha Gera Baswani. New Delhi, 2009. Image courtesy of the artist.)

MV: Since Artist through the Lens spans twenty-five years, what happens to these fragments of memory over time when you look back at them for an exhibition like the Chennai Photo Biennale? How do you engage with the simultaneity of remembering and forgetting?

Manisha Gera Baswani: This project began first with documenting Mr. Ramachandran, my guru. He was such a recluse that I decided to photograph him in his home and studio, which is another archive that has not yet seen the light of day. But it has been thirty-seven years of archiving him. As I did so, the camera became a friend. I started taking it to my artist friends’ studios, not realising what I was doing. It was a junoon (madness). At an event where artists were asked to speak about their process, someone told me that they had heard about my painting practice, but why not about my photography? And that is when I realised that I had a decade of documentation. I did not plan to make it a project; it happened organically. Over time, this act of revisiting the archive, especially in the recent past, has become a part of my visual practice and has become intertwined with my other projects, such as the Partition Project. When I went to Pakistan for a painting exhibition, I went about photographing the artists. But as I was photographing them, I heard stories about Partition. While these artists were from Pakistan, their parents or ancestors were from India at some point in time. There are many ways in which the act of looking back enters my practice, and more so at an accelerated pace recently.

Himmat Shah in his studio. (Manisha Gera Baswani. Jaipur, 2010. Image courtesy of the artist.)

For instance, one significant thing has changed in the process of looking back—earlier, I was photographing the artists for emotional reasons. So if I would go to Mr. Ramachandran, Paramjit and Arpita Singh, who were my teachers, or Anjum Singh and Himmat Shah, who were my friends, for me, it was not just documentation; I wanted to catch their essence. But when I realised the project was quite exhaustive, I was transformed from being a visual artist capturing other artists into an archivist. In that sense, not all photographs have the quality of a painting, which is how I went about capturing them initially. Some now delve towards documentation. So my project oscillates between the two. And now, twenty-five years later, I am revisiting this and thinking about who I have not yet photographed.

There are bound to be erasures as remembering and forgetting exist simultaneously in very organic ways. For instance, I had gone to Prabhakar Kolte’s studio, and I asked him if any of his teachers were still around. He said that there were two, but they were in their late eighties and nineties. I asked him if he could introduce them to me. Now, it is his memory that helps counteract the art world's erasure. In my own capacity, I am trying to do as much as I can. I would like to do more, but this is a largely self-funded project, and I undertake it alongside my art practice. I feel like a visual caretaker of the Indian art world—not that I intended to be, but I am just so happy that I have been able to capture twenty-five years of my generation of not just the artists, but also writers, gallerists and curators.

A. Ramachandran in his studio. (Manisha Gera Baswani. New Delhi, 2014. Image courtesy of the artist.)

MV: Can you tell us a bit about the role memory has to play in revisiting a space to document it through a photographer's lens in your series As close as it gets?

Vivek Mariappan: The idea for this project began in 2019 during my artist residency in Landskrona, Sweden, a small town where I focused on the built environment and how it made me feel. It was my first time outside the country, and I sensed a certain coldness—both in the city's architecture and its people. Scandinavian culture places a strong emphasis on privacy and personal space, which felt unfamiliar to me. I was used to photographing freely in our cities, capturing anything and everything.

When I returned home, I began documenting Chennai’s built environment, but soon after, the lockdown forced me to move back to Erode. Rather than starting a new project, I focused on sustaining my practice. Looking at my town from a point of memory allowed me to see it with fresh eyes. Revisiting familiar places felt similar to my experience in Sweden, where I spent hours each day photographing. I approached Erode with the same mindset, realising that, in many ways, these places—though deeply familiar—still felt new to me.

From the series As close as it gets. (Vivek Mariappan. Erode, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Most of my imagery is deeply influenced by literature. Tamil writer Perumal Murugan comes from the same landscape as I do, and I first encountered his work during my college years. Since then, I have been fascinated by how he writes about people’s lives intertwined with the land they occupy—how the landscape shapes them and how they, in turn, shape it. While living in an urban environment, his stories took root within me. When I began venturing out to create these images, I found echoes of his writing reflected in the world around me. For instance, in this series, there is an image of a hay bale between houses. The reason I was able to notice such elements is largely influenced by the worlds I have encountered through his writings. So I believe his work has always been an anchor, drawing me back to these landscapes.

From the series As close as it gets. (Vivek Mariappan. Erode, 2021. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I started photographing in and around the town of Erode daily from January 2021, and by September, I had nearly mapped out my entire town, exploring every street. At that point, the only place I had been sharing this series was on my Instagram. I wanted to create an archive to show people what I had been working on while also refining my writing about the project. As I wrote about my attempts to reconnect with my hometown and find my bearings in this place, I kept asking myself: Is it enough now? Have I found it? But it never felt complete. There was always a lingering sense of distance, perhaps because I continue to move between Chennai and Erode. Each time I return, it feels as though I have to start all over again. Eventually, I realised that I may never be fully rooted here—I am always going to remain in between. This is as close as I can get to this place, and I have made peace with that.

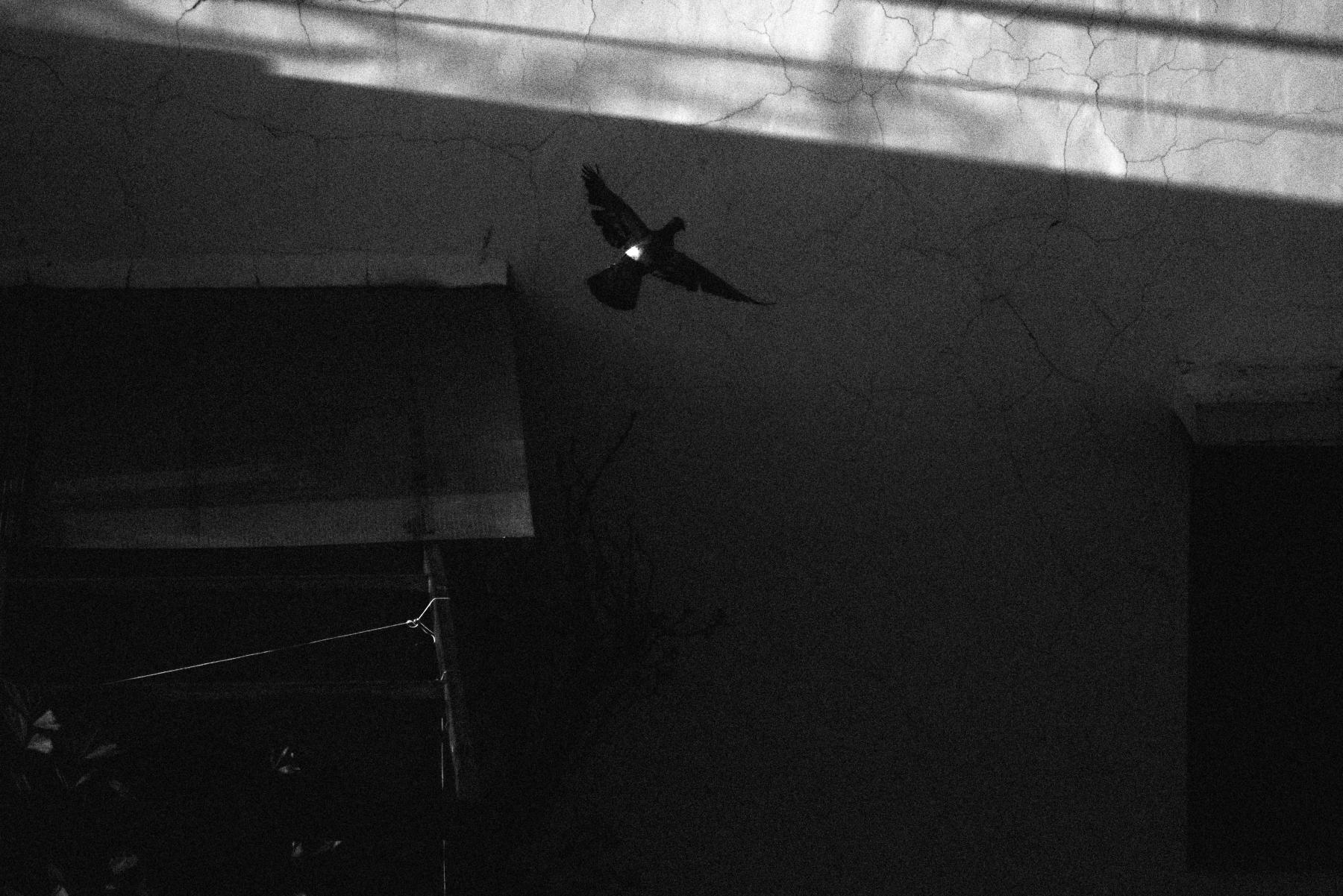

The Liturgy of the Lost Bird (Alina Tiphagne. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

MV: Can you tell us about how you navigate autobiography as something that exists in the space "between what is remembered and imagined” in The Liturgy of the Lost Bird?

Alina Tiphagne: The straightforward answer is that when you do not know something, you make it up—artistic license and all. As a child of adoption, like my father and my nine-year-old niece, I constantly wonder about my biological family—what it truly means to have roots. So when I began working on The Liturgy of the Lost Bird, which originally took shape as Nana’s Clothes, I quickly realised that I needed a format that could hold the complexities of my context—the context of both a found family and the queer community.

At its core, the work is preoccupied with how memory functions through a queer lens—how it distorts, erases, remembers and embellishes over time. I am drawn to the idea that even what we consider “real” is shaped and made credible through the act of storytelling, and what this means in a time when it is becoming increasingly difficult to discern truth from fiction. I think of my approach as a way of making space for multiple truths to coexist—where autobiography is not a rigid container of facts but a site of possibility and collectivity.

The Liturgy of the Lost Bird (Alina Tiphagne. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

The Liturgy of the Lost Bird exists in a liminal space where autobiography is not a fixed account of the past but an ever-evolving, shape-shifting terrain, informed by the limits and possibilities of memory and time. It acknowledges that personal, familial and social histories often exist in fragments and epiphanies, and that what one ultimately sees depends entirely on where they stand—or where they have been positioned. Rather than attempting to reconstruct a singular, definitive narrative, I let the material guide the story in the edit, engaging with the inherent push and pull of remembering and forgetting. I worked with found and made images, alternative darkroom printing processes, archival material and stop-motion video to reconstruct narratives—allowing text to operate as both a companion to and an extension of image sequences. Text did not emerge solely from loss and despair, as suggested by authors like Hervé Guibert, but for queer lives, for histories written in the margins, even the image does not guarantee legibility. In my practice, text and image exist in tandem—not as substitutes for one another but as echoes, distortions and white noise. Text does not arise solely from the despair of no image, but from the necessity to reimagine and create counter-archives that hold space for multiplicity.

The Liturgy of the Lost Bird (Alina Tiphagne. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Memory is political. In a country where identity is both celebrated and legislated, where rights are granted and revoked, where queerness is made hyper-visible in one moment and erased in the next, the personal is never separate from the collective. In this sense, the lost bird in the title is ubiquitous—moving through stories of grief and loss, embodiment and separation, “…wandering the forest only to be swallowed by the sea.” It is a disfigured, mutable body that is offered at the altar, nostalgic yet finding solace in memory—both remembered and imaged.

The Liturgy of the Lost Bird (Alina Tiphagne. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Can the image, found and made, invisible and/or obscured, oblong and shapeless, be a site of both rupture and reclamation of one’s identity? My work situates itself at the intersection of art and the everyday—reflecting on daily encounters—with a photograph, a memory, or a passage from a book from a queer perspective in the context of India’s social justice landscape today. I invite readers to consider identity not as singular but as a living, ever-evolving process that ties with—and is in turn tied to—memory, the experience of time and space and the collective imagination.

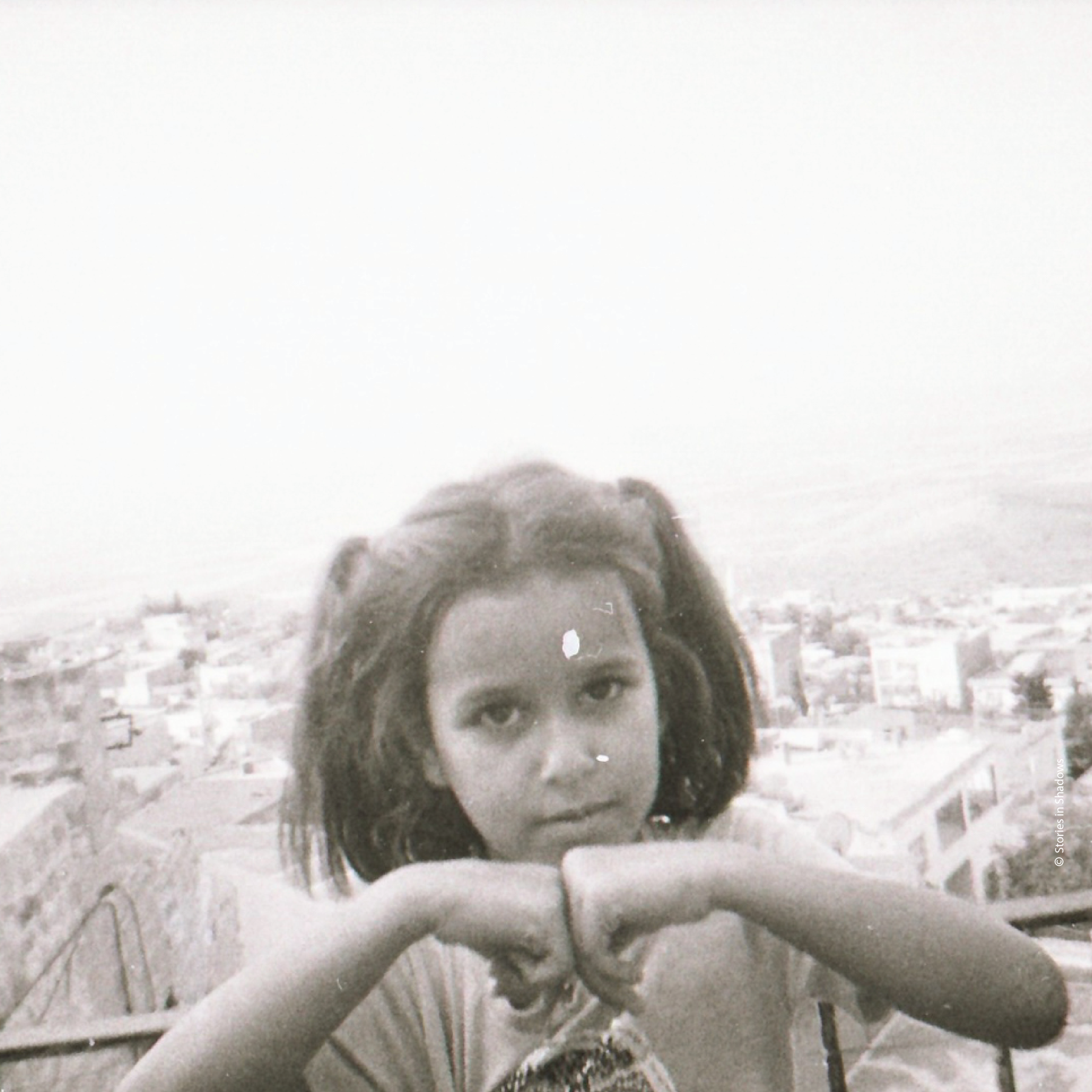

“I wanted to capture photos of my sister Meryem and the view of Mardin . . .” (Fatma [aged 10]. Mardin, 2024. Image courtesy of Fotohane.)

MV: As Fotohane Darkroom works with refugee and local children in Mardin, Turkey, to tell stories and document their experiences, can you tell us about how you use darkroom photography to help them come to terms with memories that may be traumatic?

Amar Kiliç: At Fotohane, we are trying to use photography as a form of therapy. At the beginning of the workshop, children often wonder: “Can we do it? Is it possible for us to do this?” But as they attend the workshop, they realise that it is a safe place for them and that they can make their own rules. During the workshop, the children get a chance to capture photos and then to come to the darkroom to print them. For them, the darkroom is like a magic room because they can explore and experiment. For instance, they have tried working with double exposure and other techniques in their photographs. Especially with analogue photography, it is a totally different experience because the children can see their photos being printed out. Because they are conscious about not wasting film, there is a greater intentionality in how they choose to frame their images. With analogue photography, because it is limited when compared with the digital, you have a greater connection. It may be a difficult process to process and print the images, but the children always exclaim “Bismillah” or “Mashallah!” when the photographic print is revealed. The process is very physical, so there is a feeling of being completely involved and a sense of wonder.

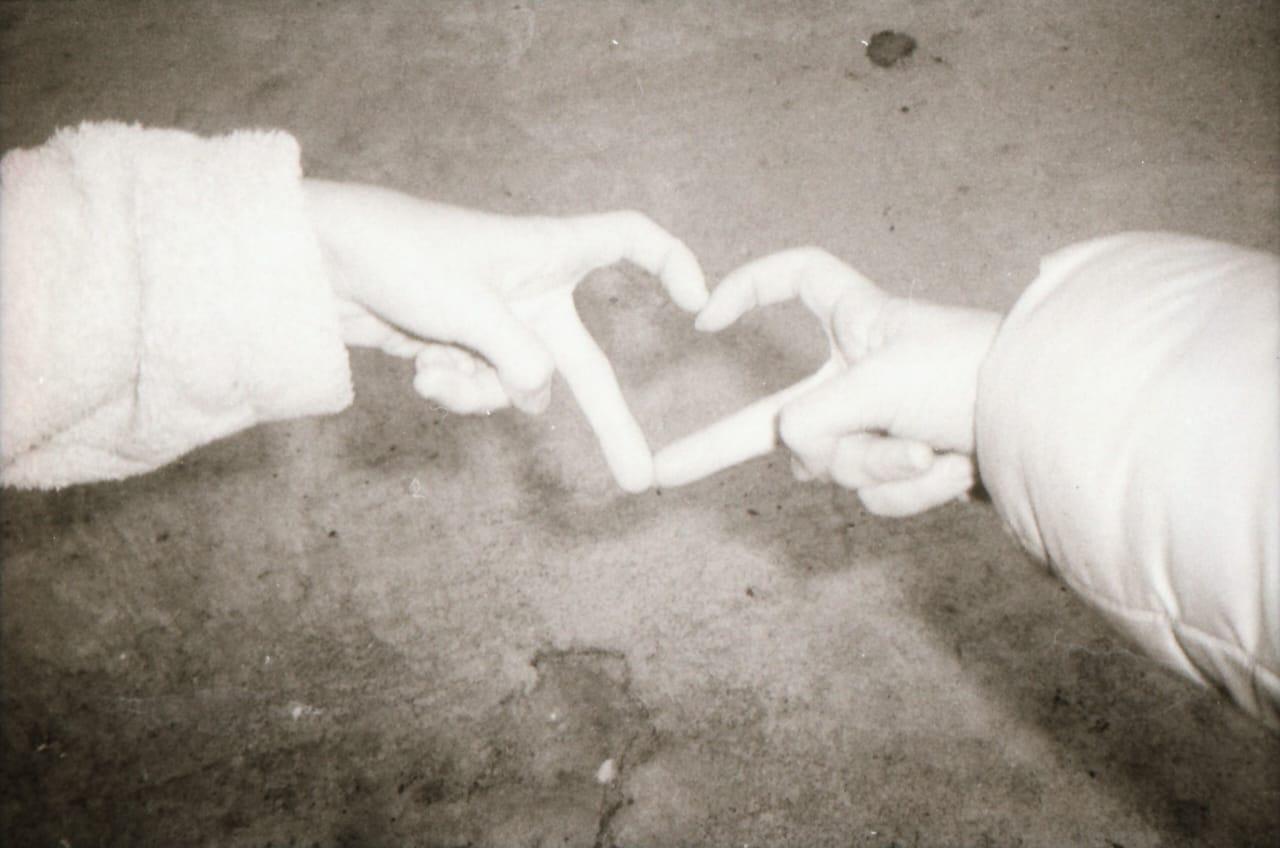

"She wanted to make a connection related to humanity, saying, 'In a group without identity, love and friendship take over discrimination. In this photo, I wanted to show love and friendship.'" (Ciwan [aged 13]. Mardin, Turkey, 2024. Image courtesy of Fotohane.)

Serbest Salih: We are trying to use photography as a universal language. Mardin is very rich culturally—there are people from diverse backgrounds, including Kurds, Arabs, Armenians, Assyrians, Syrians, etc. We try to use photography as an alternative way of expression for the children. It becomes a creative way to raise awareness and address the social and political issues particular to this region. As part of our workshops, we have photowalks and discussions around themes such as gender equality, child rights, peer bullying, environmental concerns and so on, which are addressed through the medium of photography. We see this as a shared responsibility because all these issues directly impact the children. Fotohane is imagined as a place for children to share their thoughts, their knowledge and their creativity. We strongly believe in the participation of the youth and children. Over the course of the workshop, you can see the children transform in the way in which they participate and engage with the photos, including providing constructive criticism to each other. The photographs present the children’s perspective of their city and life every day.

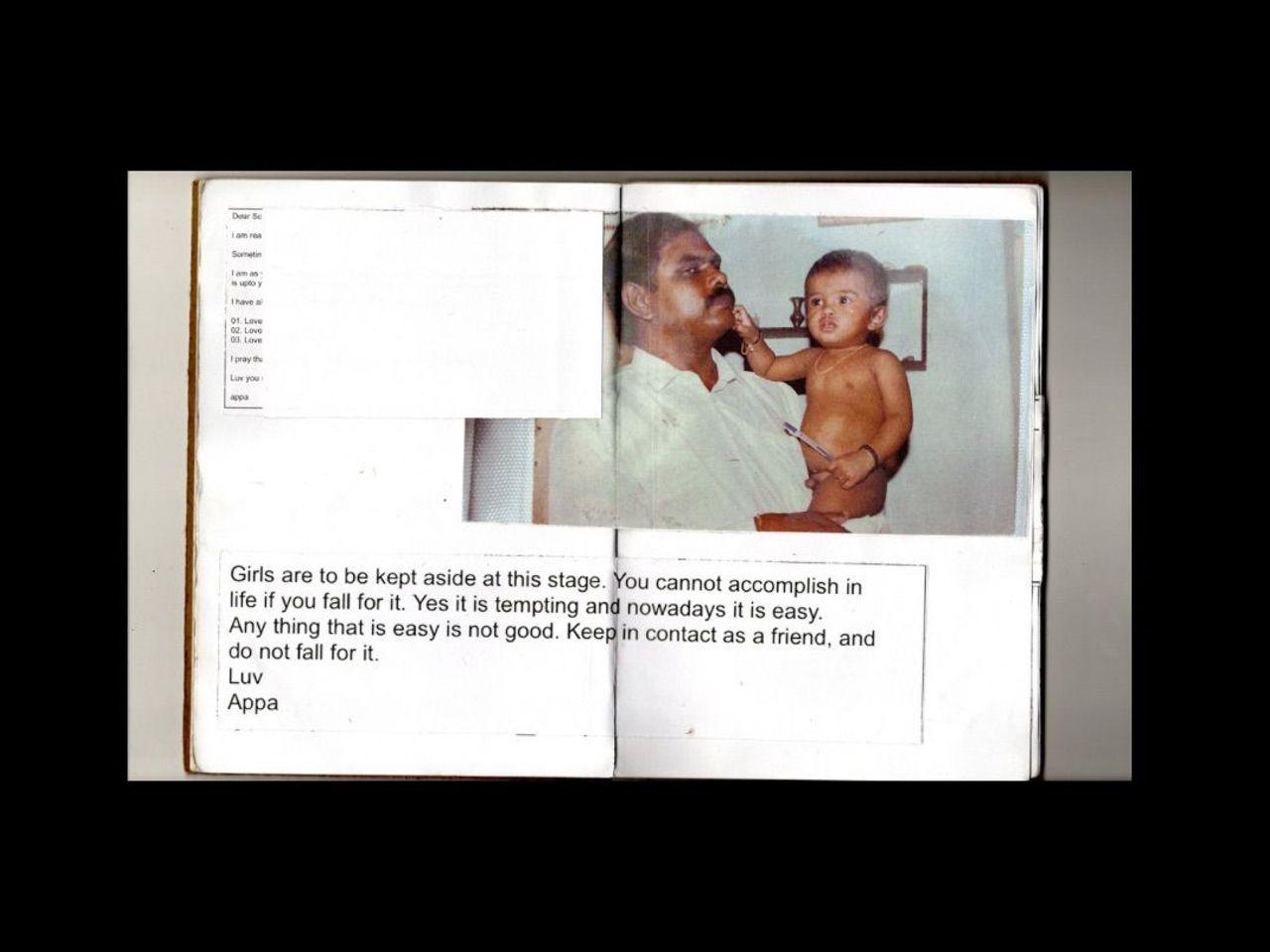

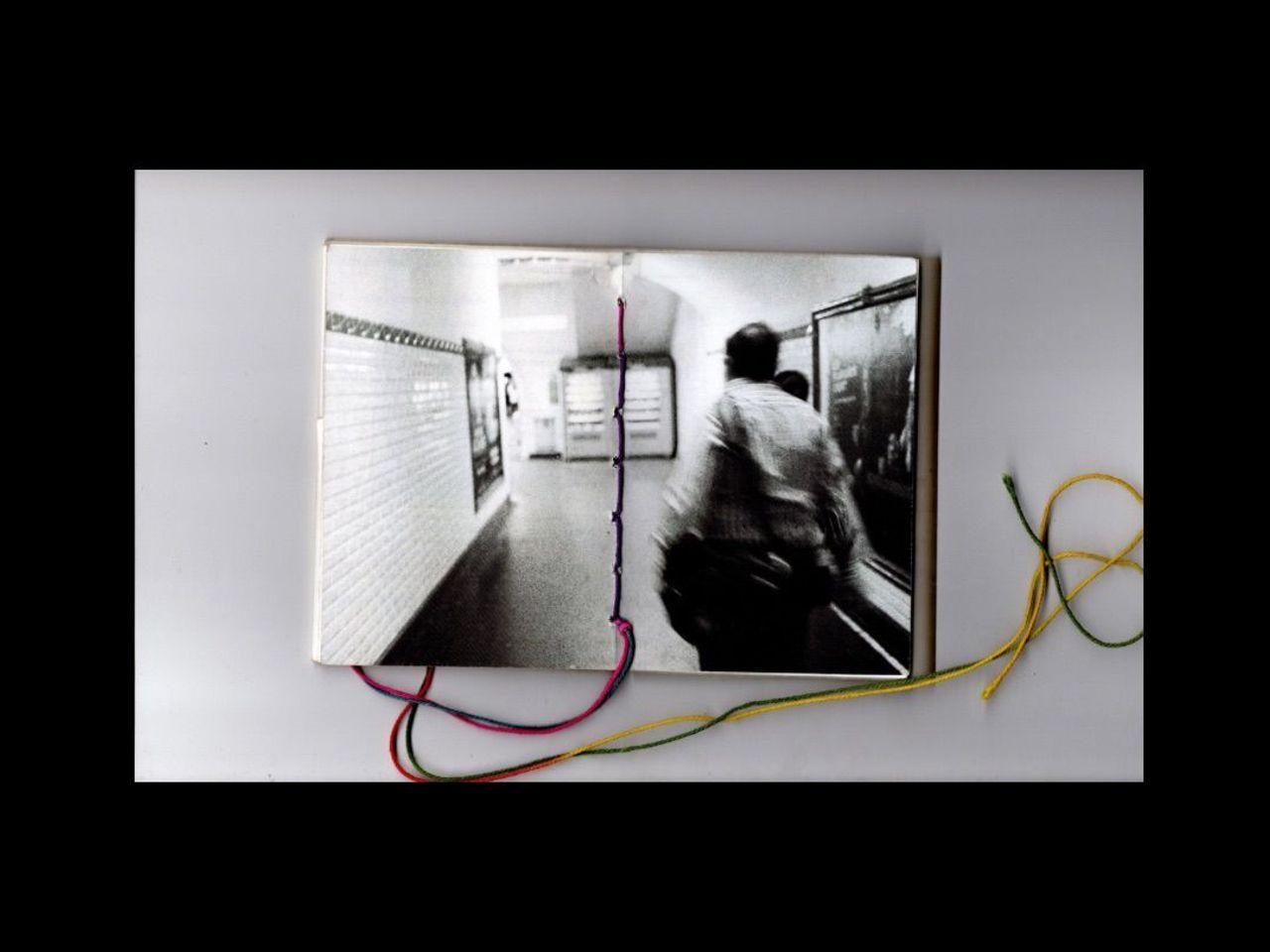

Spread from Last Seen 24 Sep 2015. (Steevez. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

MV: Since Last Seen is such an intimate look back at your relationship with your father, can you tell us about your process and why you chose the form of a photobook?

Steevez: I have been taking the screenshots that form the photobook from around 2015. After the passing of my dad, I went back to the emails that he had sent and realised there were quite a lot of emails that I had not opened or answered back. After the loss, that kind of felt weird, so one of the ways that I could keep traces of it was to take screenshots. I ended up with a few hundred screenshots of the things that I wanted to hold onto in terms of memory. I did not really know how to proceed with it because it was emotionally challenging, but I would always go back to it over the years.

Spread from Last Seen 24 Sep 2015. (Steevez. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

One of the initial ways that I started working on this project was in terms of thinking about the medium of photography. I was exploring questions like: “What defines a photo? Should camera be the object that produces what we call photos?” I also branched out to machine learning and visual generation from AI in a very nascent stage, around five years ago. Then I found a connection because I realised that screenshots are saved as .JPEG. So they could be considered as photos. It does not really have a camera to produce a photograph in a traditional sense. I wanted to work on these screenshots by thinking of them as photographs in this way.

.png)

Spread from Last Seen 24 Sep 2015. (Steevez. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Last year, I also became interested in the physical act of bookbinding. I was learning different binding techniques. Since I did not have a laptop, I started making these blank page books, wherein I printed the screenshots and tried to order them. I made multiple dummies. However, the design was not cohesive because I had taken the screenshots over a period of time. At that time, it was more of a high pace drama sort of story that I had built around the Kolkata incident, when my dad had died, so it was more about the death aspect of it. But I realised I needed external help in terms of structuring the project. So last year, I applied and was selected for the Image Assembly workshop, organised by Photo South Asia and conducted by Tanvi Mishra, Cécile Poimboeuf-Koizumi and Sukanya Baskar. The workshop was held in Delhi for a week and then we came back and worked on it for another two or three months. And then we had to go back in August to discuss our progress. Through the discussions and conversations, I came across this comic from Peanuts by Charles M. Schultz where there is the quote “We all die once” but Snoopy replies that “the rest of the days we live.” So that thought shifted a lot of things for me because my dad died one day but he was alive for 52 other years. So after that, the iterations that I made placed the death in a later stage of the book. As time passed, I made the narrative unfold more slowly, introducing my dad as who he was, where he started from.

.png)

Spread from Last Seen 24 Sep 2015. (Steevez. 2024. Image courtesy of the artist.)

In another conversation as part of the workshop, we discussed what other approaches could make the design more cohesive. One of the ways was to recreate the same text, but having those elements digitally created and fixed. To bring in, say Facebook’s specific design with its blue colour and a specific font. So in the second version, I created a small A6 book, and I tried to recreate the sense of platform the message was on. I consciously did not cross the line of manipulating the image—I copied the same spelling mistakes and the extra spaces to maintain the originality of it. I able to see that it was working more cohesively and people were able to get into it.

For the third iteration, I also wanted to experiment with the construction of the book to see if I could translate how memory operates in the human mind into book form. So I added flaps and transparencies to reference how memories are often overlapping and layered, such that certain memories or images came to be revealed as the pages were turned. This is the version that is on display right now at the Chennai Photo Biennale, but it remains a work-in progress.

.png)

Installation view of Last Seen 24 Sep 2015 by Steevez at Chennai Photo Biennale. (Image courtesy of the artist.)

To learn more about the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, read Vishal George’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore urban landscapes and with artists whose practices explore the theme of labour, Anoushka Antonnette Mathews' short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of mental health and neurodivergence and with artists whose practices explore themes of bodies and landscapes, Upasana Das’ short interviews with artists and practitioners exploring forms of community building and with artists whose practices explore themes of power and representation, Kshiraja’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of landscape and history and with artists whose practices explore themes of myth, ritual and identity, as well as Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with the curators of the primary shows.