Representations of Labour at the Chennai Photo Biennale

What is the capacity of photography to capture labour? What stories can pictures tell us about labouring bodies? Wielding a camera helps understand relations of labour in our social milieu while also indicating one’s own labour. Four projects featured at the Chennai Photo Biennale reflect further upon the theme of labour present in their works. Through Zugvögel (or Migratory Birds), Kiki Streitberger spotlights the stories of farm helpers travelling to Germany for short spells from Eastern Europe. MOMus–Thessaloniki Museum of Photography coordinated students across schools in Greece and Belgium to bring their unique perspectives in capturing facets of labour in the showcase People at Work. Children worked with CEDAR to capture images of workers that help represent their marginalised lived experiences in Chronicling the Toils of the Margins. Responsible for curating a tribute to Navroze Contractor in a retrospective titled Photography Strictly Prohibited, Anuj Ambalal speaks to Contractor’s relationship with labour in light of the auteur’s immense legacy.

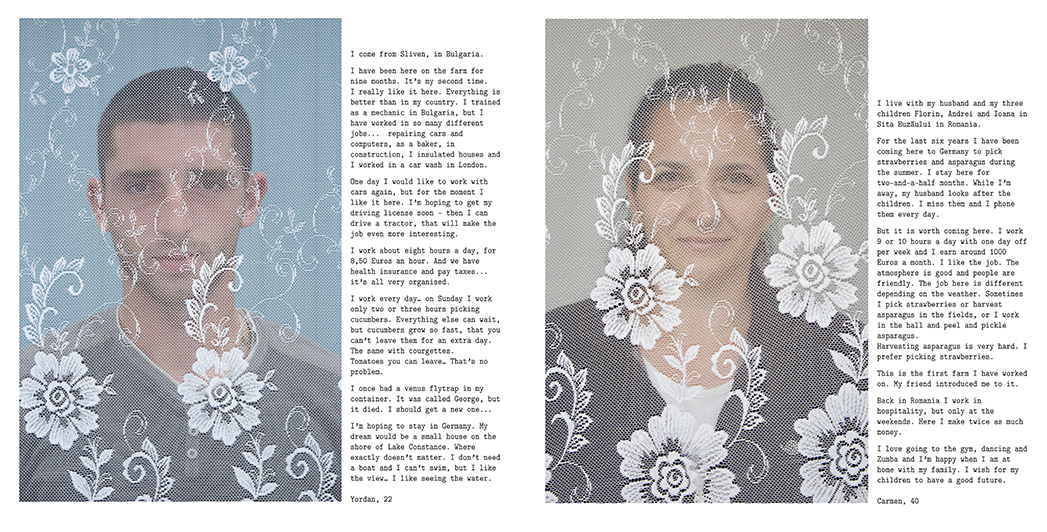

The first time I visited some farm workers ‘at home,’ I noticed the curtains at the entrance to the containers they stayed in. While they were meant to keep flies out, they also concealed the interior from view. So, it seemed only natural to photograph them partly hidden behind those curtains. (Kiki Streitberger. From the series Zugvögel. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Vishal George (VG): The commodification of labour and current consumption practices obscure the labouring persons responsible, reducing them in popular political discourse to ‘migrant labourers.’ How can the camera then become a tool of intervention to tell their stories? Did this project force any reflection upon the differences between the labour of the farm helpers and your own labour in photography?

Kiki Streitberger: I am not sure those people are deliberately hidden. Unfortunately, who they are is simply not relevant to most consumers—like everywhere, if the system works, we rarely check why it works. The rise of fast commerce means that we only care for our products being easy to procure and cheap. People do not see the need to look any further into how this is possible and who makes this possible. We tend to only look closely once something no longer works. The inspiration for my project was simply my own curiosity. I love strawberries, and in Germany, they are sold in little booths by the side of the road. I wanted to know who the people were that picked them and so I went on a little quest to find out.

It struck me that these workers existed in a parallel world—hidden from sight, yet just down the road from us. At the same time, I really appreciated the ‘Eastern European aesthetic’ the curtain designs brought to the portraits. (Kiki Streitberger. From the series Zugvögel. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I also do not believe we “reduce” them to the term migrant labourer here. In German, they are referred to as Erntehelfer (farm helpers), which more accurately reflects their role. They simply come from elsewhere to do a job that people in our own country either do not want to do or cannot do as efficiently. One of the great advantages of the EU is the freedom to live and work across the entire bloc. While, as in any group, there are some who exploit their workers, most of the people I have spoken to see it as a win-win situation. Farmers gain reliable, skilled workers, and the workers themselves earn significantly better wages than they would at home.

I do not think you can compare the labour involved in the two jobs. Several farmers attested that I would be a very useless farm worker, for I cut the asparagus too short. I not only picked not enough strawberries, but also all the wrong ones. I am not sure I would even want to compare the two. In this particular case, I took pictures while other people worked, and I can say I came to understand a vast difference between our works.

Salt pan workers taking a break (L) and hard at work (R). (From the series Chronicling the Toils of the Margins. Image courtesy of CEDAR.)

VG: How do children’s lived experiences impact their understanding of labour and the choices they make in what they shoot? Did the experience of participating in the project produce a noticeable change in their understanding of and attitudes towards labour?

Basheer Khan: The children’s lived experiences shape both what they see and how they see it. Many of them come from communities where hard labour is a daily reality—whether it is their parents working long hours in harsh conditions or their own responsibilities in the household. This proximity gives them an intuitive understanding of toil, struggle and endurance. In terms of content, their choices reflect what feels familiar yet often unseen—hands worn by labour, faces lined with exhaustion, or spaces that speak of relentless effort. Aesthetically, their framing, composition and use of light often capture rawness rather than staged perfection. Their perspective is different from an outsider’s because they see both the pain and the quiet resilience in work. Their images do not romanticise labour but rather express an emotional truth.

Image capturing a space of work and equipment used at a fireworks factory. (From the series Chronicling the Toils of the Margins. Image courtesy of CEDAR.)

Children do not approach labour with preconceived notions. Their photographs are often intimate rather than distanced. Instead of just showing struggle, they capture small, humane moments—like a tired worker laughing for a second or a pair of hands pausing to wipe sweat. The children were drawn to different elements based on what resonated with them. Some focused on people—their expressions, their exhaustion, their moments of rest—perhaps because they see similar emotions in their own families. Others captured hands and body parts, highlighting the physical strain of work. The textures of calloused skin, dirt-streaked faces, or bent backs tell their own stories. Then there were those who turned their cameras towards tools and spaces, all of which symbolised the conditions under which labour happens.

Yes, there was a shift, though it varied from child to child. Some children, who had always seen labour as just a part of life, began to look at it with new eyes—recognising its weight, its struggle and its human cost. Others started to see psychological depth and resilience where they previously saw only hardship. For many, the act of capturing labour through a lens made them more aware of the invisibility of these workers in mainstream narratives. They began to ask: Why are these workers overlooked? Why do some jobs get respect while others do not? Photography helped them reflect on the dignity of labour and the inequalities surrounding it.

An image focusing on the hands of a worker at a matchbox factory. (From the series Chronicling the Toils of the Margins. Image courtesy of CEDAR.)

VG: What professions did the participating students gravitate towards? In clicking People at Work, what aspects do you think drew their attention the most? What fresh perspectives did you see children bring to capturing labour in this project?

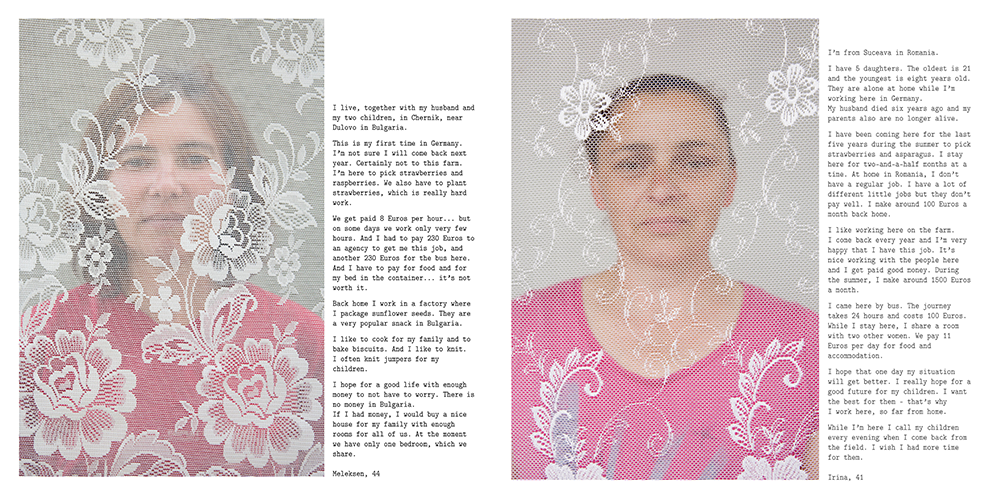

Alexandros Michael: Due to the need for protecting personal data, the students were instructed not to photograph faces directly but to focus on other aspects of each professional. The young photographers truly impressed us with their creativity in selecting subjects for their shots. The students’ choice of professions to photograph was impressively diverse. Among the subjects they captured were a police officer, a baker, a teacher, a painter, a truck driver, an ophthalmologist, etc. It was fascinating to see how this project not only brought them closer to different professions but also sparked their curiosity about photography.

Image of a child’s hand alongside a professional’s. (From the series People at Work. Image courtesy of Thessaloniki Museum of Photography.)

They were particularly drawn to the spaces where professionals carried out their work. To bring life to their artistic pieces, they also made sure to photograph the professionals in ways that highlighted specific body parts—such as hands holding objects related to their profession or distant shots of the professionals actively engaged in their tasks. It was fascinating to see how they could capture the essence of each job through these unique points of view.

In this project, the students brought a fresh perspective to labour, focusing on the small, often overlooked details that professional photographers might miss. While professionals tend to capture the grand narratives of work, the students’ work was intimate, focusing on objects and workspaces, as well as the subtle moments of workers in action. Their approach, driven by curiosity and a sense of discovery, allowed them to showcase the artistry in everyday labour. They were less concerned with the grand narrative of work and more focused on capturing the hidden moments and emotions that make each job unique. This allowed them to offer a perspective that was both personal and insightful, revealing the beauty in the mundane. They captured not just the task but the deeper connection between people and their work, reminding us that the most impactful photos often come from genuine exploration.

An image without color capturing the stained pants of a painter at work. (From the series People at Work. Image courtesy of Thessaloniki Museum of Photography.)

VG: For a person with such diverse interests, what was Navroze’s attitude towards his work? Having perused through a lifetime’s collection of his work, could you speak to the insights you have gained on his approach towards labour?

Anuj Ambalal: Navroze lived life fully, and all his interests were part of this sentiment. They were an extension of his persona—his very being. It is impossible to isolate these to understand him. I believe his varied interests in life were what made him and his work so compelling. You cannot untangle the cross-references in his mind that shaped his work. How can we say that his deep understanding of music and rhythm did not influence his compositions in cinematography or photography? His study of fine art and art history at MS University, Baroda, would have also influenced his compositions. Navroze loved people, and this was evident if you travelled with him. He was equally engaged when conversing with intellectuals as he was with the man on the street. He relished these interactions, which also reinforced his strong political beliefs—another element that influenced his work. He approached everything with his whole being.

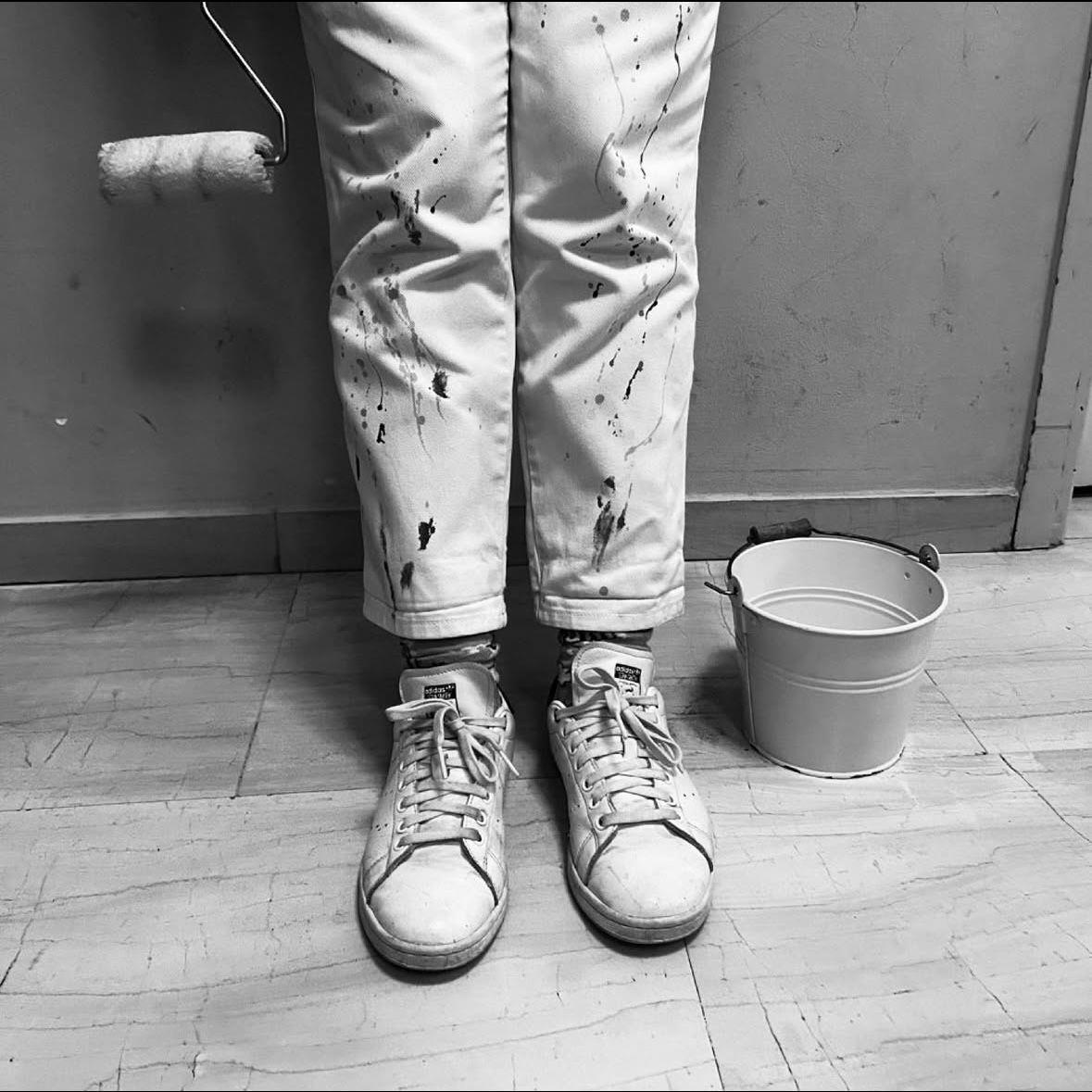

From the Navroze Contractor Retrospective: ‘Photography Still Prohibited.’ (Image courtesy of CPB.)

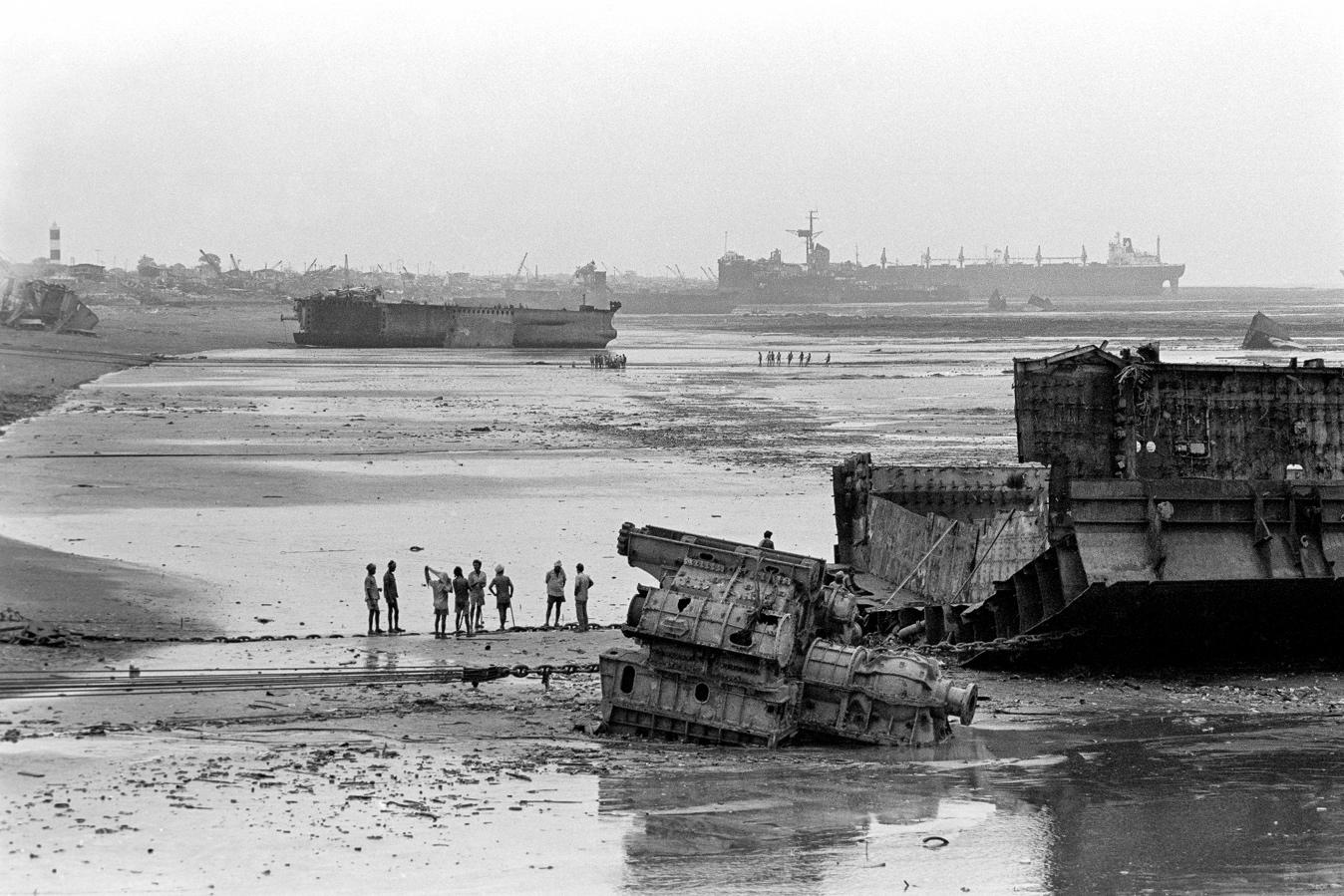

Navroze was a hands-on person. He had great respect for people who used their hands for their professions. A motorbike mechanic would amaze him more than an IT professional! If you look at his life’s work in still photography, this respect comes across. He has taken so many pictures of people at work. I remember he took a workshop at CEPT, Ahmedabad for still photography. The topic that he gave his students was “People at work”! If you study his photographs of workers (shot over four decades—and he never got tired of the subject), one thing that comes across in those pictures is his gaze towards his subjects, which is full of marvel and respect.

From the Navroze Contractor Retrospective: ‘Photography Still Prohibited.’ (Image courtesy of CPB.)

I believe that an artist’s aesthetics should inspire rather than influence your work. If not, it becomes counterproductive. Besides, in spite of the difference in our age (more than thirty years!), we were very good friends. We enjoyed each other’s work as well as company. There were many aspects to his life that one can gain from. But if I were to mark out his three qualities worth their weight in gold, they would be his zeal for life, curiosity and work ethics.

From the Navroze Contractor Retrospective: ‘Photography Still Prohibited.’ (Image courtesy of CPB.)

To learn more about the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, read Anoushka Antonnette Mathews' short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of mental health and neurodivergence and with artists whose practices explore themes of bodies and landscapes, Upasana Das’ short interviews with artists and practitioners exploring forms of community building and with artists whose practices explore themes of power and representation, Kshiraja’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of landscape and history and with artists whose practices explore themes of myth, ritual and identity, as well as Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with the curators of the primary shows.