Myth, Ritual and Identity at the Chennai Photo Biennale

Through a rumination of the creative and photographic process, the fourth Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB) gives shape to narratives around the visual production of identity. Five featured artists seek to unravel the threads of cultural identity through themes of myth and ritual in their practice. Aishwarya Arumbakkam meditates upon the idea of Tamil identity by weaving Tamil Sangam poetry into the motif of hair. Through the ephemeral elements that title her exhibition Light Salt Water, Sujatha Shankar Kumar explores the creation of invented mythologies. Radha Rathi delves into the rituals that surround the idols of goddesses in Tamil Nadu, exploring themes of femininity and the male gaze. Delphine Diallo wields mythology as a visual tool to deconstruct representations of Black women. In The Threads That Connect Us, Fotokids curates a selection of photographs from children in Guatemala, where elements of myth and fantasy allow us a glimpse into the experience of childhood.

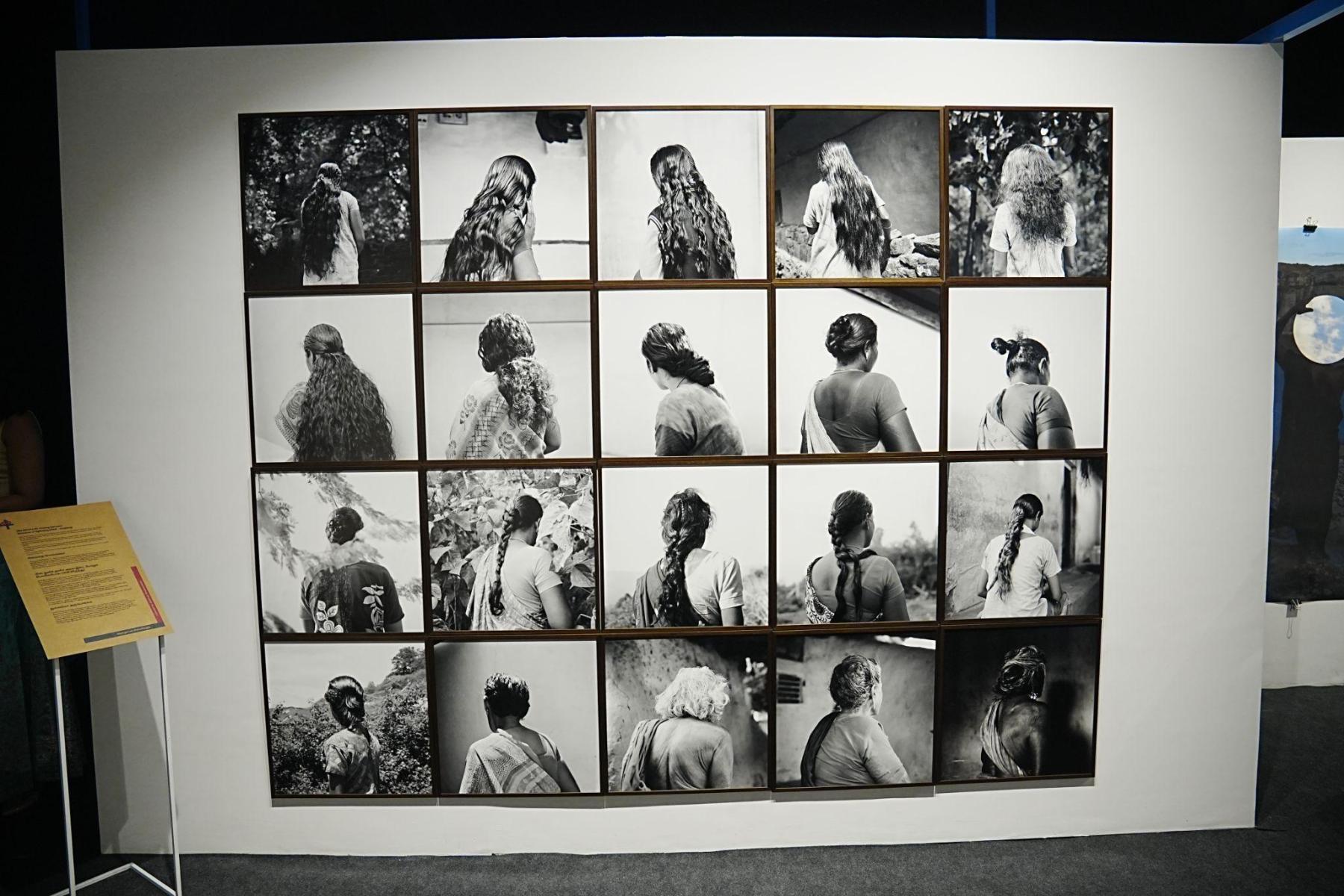

From the series Like rainclouds moving between branches of lightning. (Aishwarya Arumbakkam. 2018-ongoing. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Kshiraja (K): How do you explore Tamil cultural identity through the motif of hair in Like rainclouds moving between branches of lightning? What role did poetry play in your photographic process?

Aishwarya Arumbakkam: This is an ongoing body of work I started making in 2018, and I am still adding to it. Vaanyerum Vizhuthugal shows a selection of twenty images out of more than a hundred [photographs]. The title of this work comes from AK Ramanujan’s translation of a Tamil Sangam poem by Kapilar. These (Sangam poetry) are classical in the sense that they are from a certain era, between 100 BCE and 250 AD, but also in the sense that they have lasted the test of time and are still relevant.

Growing up in Chennai, I heard a lot of scenes, songs, stories and stereotypes that described, or were about, a woman’s hair. It is considered a marker of a certain kind of beauty, but also of character. It is an odd, tense space—because hair is part of you, anatomically, but it is often used as a tool to impose a sense of identity on you. On the other hand, it can also be wielded to create a sense of identity for yourself.

When I was young, my mother told me that there was a list of things one does not tire of looking at, based on a Tamil saying. She never told me what those things were, so it left me free to find them for myself. In many ways, hair is one of those things for me. Its formal qualities of physicality, texture, shape and movement—there is a tactile pleasure I derive from photographing these.

Installation view of Like rainclouds moving between branches of lightning at the Vaanyerum Vizhuthugal show. (Aishwarya Arumbakkam. 2018-ongoing. Image courtesy of the Chennai Photo Biennale.)

When I photograph these women, I photograph them from the back. What you see in front of them—which is behind them in the photographic plane—is the landscape. We see what they see, the landscape of Tamil Nadu. An important aspect of Tamil Sangam poetry is that it marries the idea of landscape, time, place, natural elements and human character to evoke a certain emotional tone.

I did not go about making these images with this toolbox in mind, but it often happens that you end up making a work and you come across something while reading, and you realise you are just following the path of things that have been done by this tradition before you, where you come from. That collapse of time is very interesting, and it was nice to come into that realisation; it was humbling. The verse [in the title] actually begins with “Oh! Your hair is like rain clouds moving between branches of lightning.” This gave me a clue into how I wanted to photograph this work.

From the series Like rainclouds moving between branches of lightning. (Aishwarya Arumbakkam. 2018-ongoing. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I think it was important to me that hair was not used as a façade to hide anyone’s face. These are portraits of people, of their hair. We do not see their faces, but there are many other markers of identity and character in the image. The work covers different ways of wearing one’s hair. There is the loose hair, the braid, the loose bun, the high bun, the tight bun, the flowers, the braided bun, the knot, the way hair grows out after you have shaved it in offering to a deity, or the way schoolgirls wear their hair. There are all these layers to it, and what they signify in terms of where you are as a person, in your life. For example, when you are a married woman, you would wear your hair a certain way. While these are types, I am also trying to push against those types, because it is important to know that there is not a monolith of women and hairstyles. It is a person with a braid and another person with a braid—I think that distinction is important.

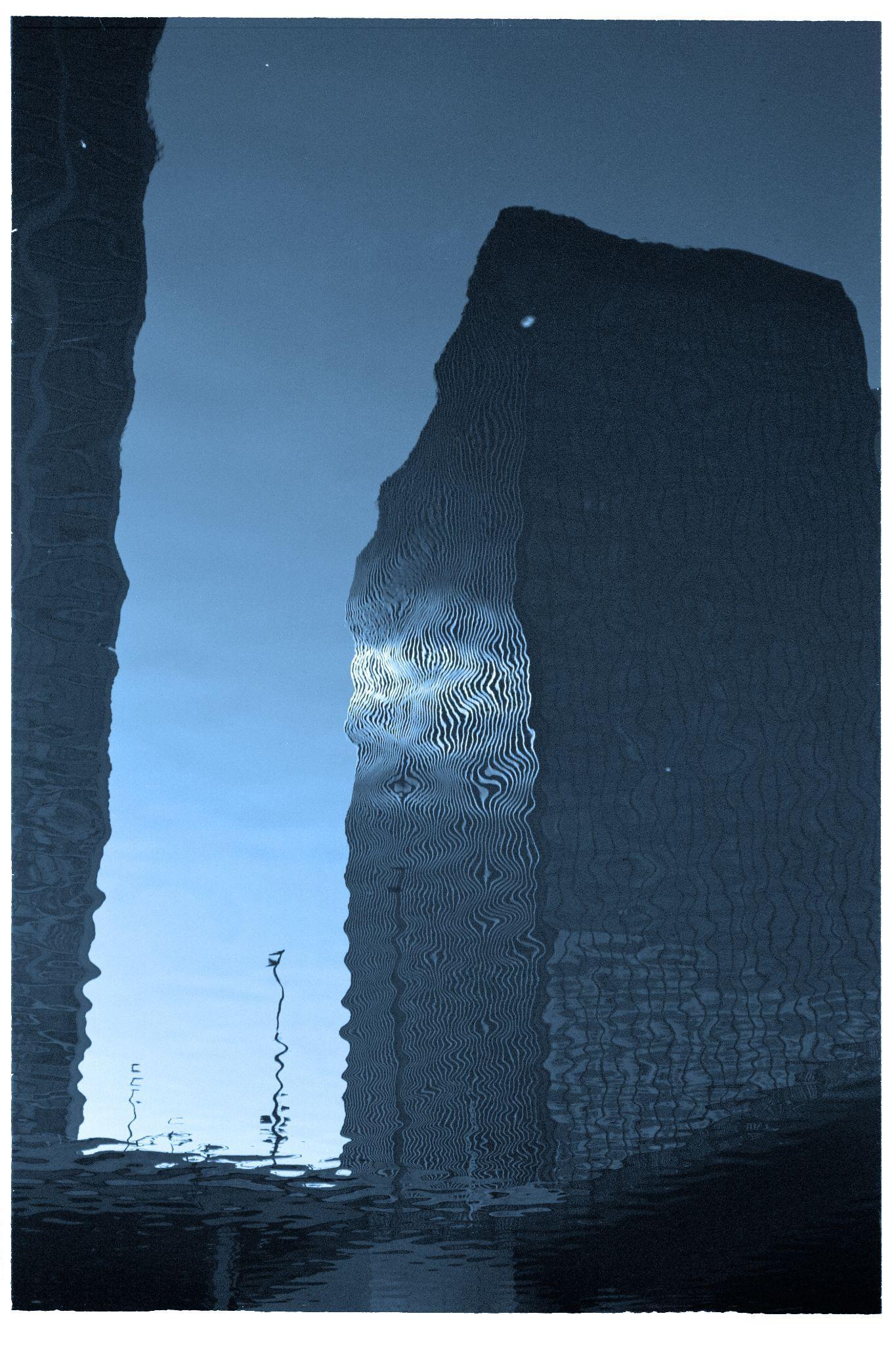

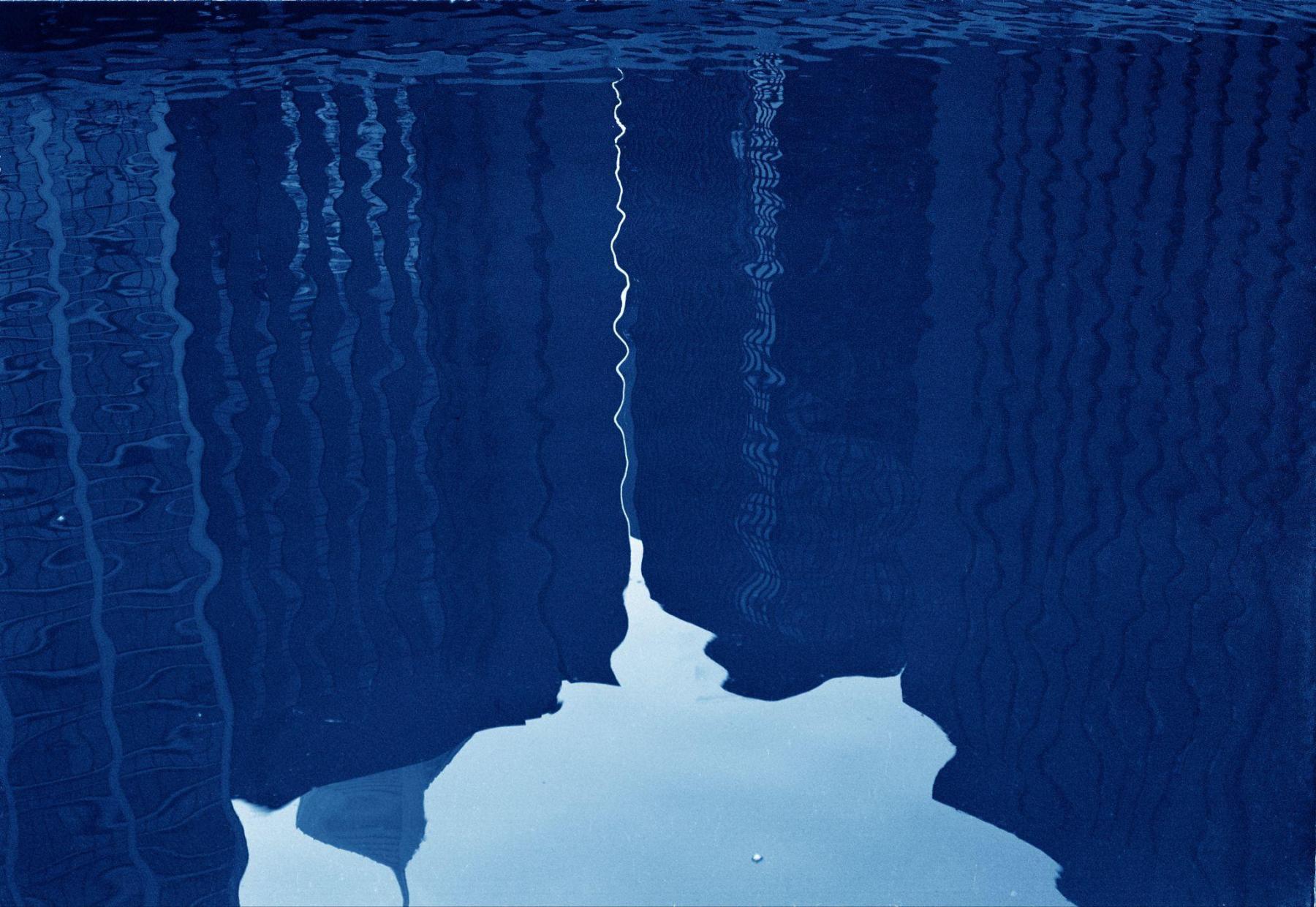

“Temporary Effervescence”, as part of Light Salt Water. (Sujatha Shankar Kumar. Image courtesy of the artist.)

K: How does the idea of 'invented mythologies' take shape in Light Salt Water? How did you go about capturing the ephemeral in the landscapes that feature in the show, and what role does the idea of Porul play in your ritual of image-making?

Sujatha Shankar Kumar: Anahita [who curated the show] and I put together Light Salt Water from photographs that I had shot over many years. I have been photographing since I was a child, and when I went abroad, the camera became a companion. I used to walk around the streets of Chicago, discovering the city's history with my camera and documenting things. I found myself by the edge of the river one afternoon, and it was really quiet, and the sunlight struck the water in a certain way. I saw the reflections of the skyscrapers in the water for those few [moments]. So, I shot the whole series of these pictures, which I call my “water pictures.” I think I was brought up to understand that everything is transient. But you are faced with that a lot more when you are away from familiar people and places. When I read up on the history of Chicago, I realised that the river once had a marshland by it. I imagined how [from that] it had become this very hard-edged city now, with skyscrapers sitting right on the edge of the river. It was like the same waters held the past, the future and the present. The water held the reflection, and a reflection is ephemeral.

It was less about going and asking a person for a story and more about discovering the people through the place. Text and spoken word have always been a part of everything I do because they draw the viewers in and give them my side of the story. So, the whole thing was called Transient Places. The Porul series started off as something called Topographies—“topos” is place, “graphia” is writing. So, it is place-writing just like photography is light-writing.

“Lost City”, as part of Light Salt Water. (Sujatha Shankar Kumar. Image courtesy of the artist.)

When I started researching, I found that the word porul has different meanings. It means the essence of life, the substance and its wealth. It also means light, strangely. This was almost an epiphany—the fact that in India, we had this concept that porul is light, and light is matter. My mother and her friends used to recite the Thirukkural, but I did not realise that it also had a book of Porul. The Thirukkural, which means sacred verses, are philosophical on one hand and practical on the other.

When I think about my photographs, they have a geometric structure, which shows you the practical side of things. For example, I have to stack this much cloth and it has to fit in this much space. I also write some text for each photograph, like I did for Not one size fits all. There is a very functional side and also a philosophical side to it.

From the series Porul in Light Salt Water. (Sujatha Shankar Kumar. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I am fascinated by Joseph Campbell’s work too. In The Hero's Journey, the hero figure goes through all these troubles to arrive at something, and you want to identify with their struggles. You want to find a way to understand life, but you cannot get it by going through practical things. So the ‘myth’ helps you go beyond what is offered. With photography, it is similar, because there is a moment you capture that lets you enter some space that is beyond these prescribed or defined ideas that you have in life. If you can do that for your viewer, you have succeeded as an artist.

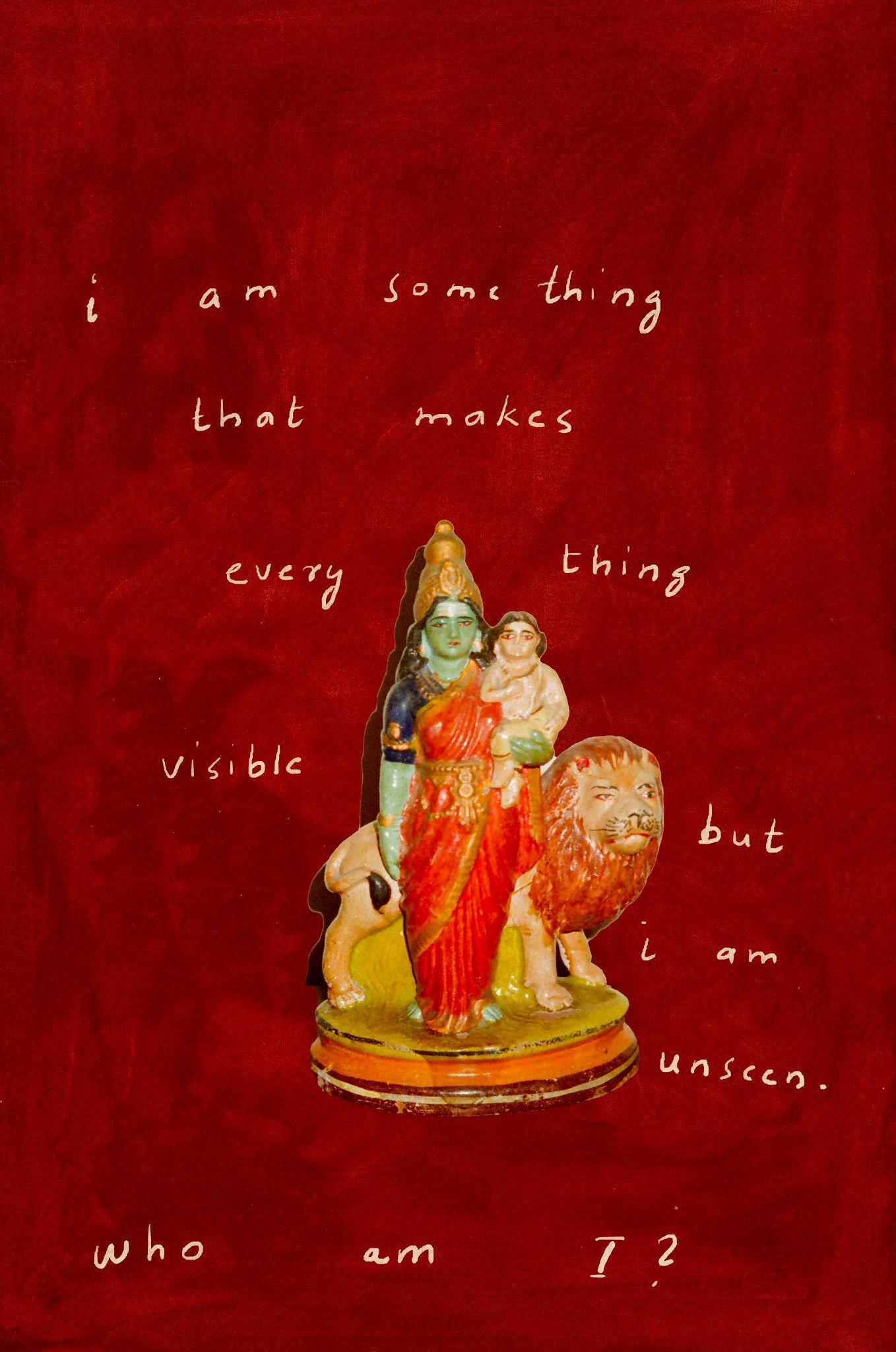

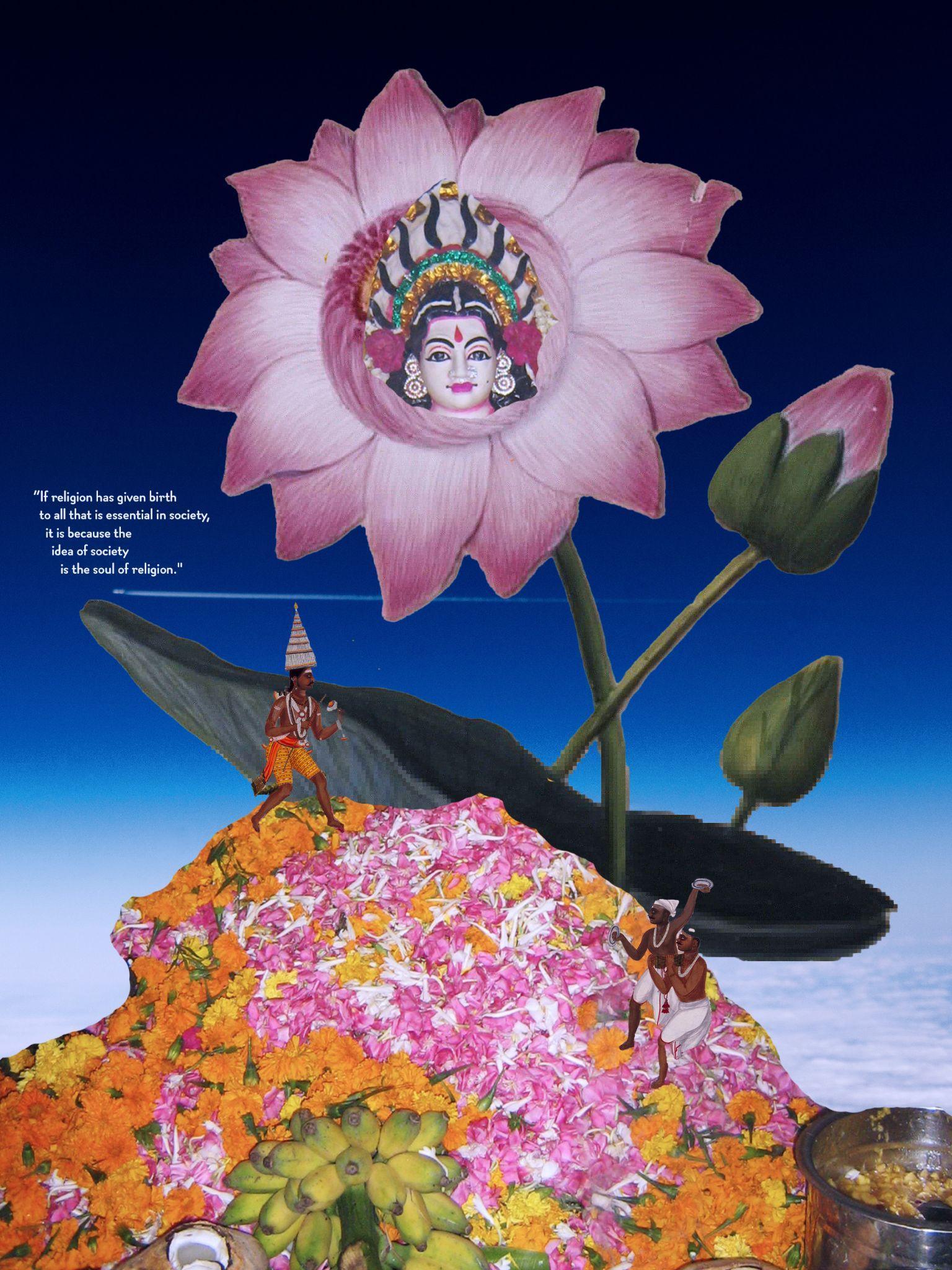

From the series I Glitter You With My Thousand Eyes. (Radha Rathi. Image courtesy of the artist.)

K: In I Glitter You With My Thousand Eyes, you layer photographs of goddesses with questions and other visual elements. How do you explore the relationship between mythical figures and real-world social identities through the project? Did the ritual of adorning the deities inform the process of image-making?

Radha Rathi: Joyce Flueckiger, a theologian, poetically asks, “What can we learn about the Indian goddess—her agency, her limits, her desires—through her interactions with humans?” To put it simply, this explains my approach to this work and my explorations in it. Because the quote is open, the work is also open to a lot of interpretation. Which meant that the way people relate to the [layers of the] pictures and questions is very different from the way I saw it. After I put the work together, I have been reinterpreting the work and questioning what called out to me and why I wanted to present the images with these questions.

I think the idea of a ‘free woman’, like the idea of a goddess, is a myth. What does that mean in sociocultural terms, and for people like you and I who are part of this world? How do we understand it, individually and collectively? It is a shared feeling and a personal quest as well. This angle brought up questions like—these goddesses who are adorned or dressed like this, does that only come from the male gaze? Is it a tradition that has existed before you, and that you have seen before, or is it beyond that? Because each person has their own way of combining the jewels, or picking the adornments and the sari for the goddess. And after the goddess is adorned, she is viewed by men and women. All of us have the desire to be seen, or the need to feel seen, physically and metaphysically speaking. So we dress well and we make sure our hair looks good—to be seen by ourselves, but also people around us, people we know and the people who love us. So, it is individual but tied to the collective. The goddess is a mythical representation of a woman, and the idea of free woman is a myth. Can it ever exist? I do not think so.

From the series I Glitter You With My Thousand Eyes. (Radha Rathi. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I used photography as a medium because the way the goddesses are adorned is very [visually crowded] and the large-format imagery allows that to stay with you. Sometimes, due to access, you can photograph [something] quickly, so that it gets recorded, almost like a family photo. I wanted to document this without staging it because it was already staged [so to speak], in the temples where I was permitted to shoot.

I am a North Indian, born and raised in Chennai, and I have seen goddesses [represented] very differently in my home. For example, Durga is fierce, but the visual has a calm, mother-like presence. The goddesses in my photos are also of the mother [archetype], but their presence is more raw, feminine and sexual. I was really attracted to their form; you cannot ignore or miss it. There is something [interesting] about the inanimate creatures who take up so much of our time in terms of devotion or transactions.

When you go to an Amman temple, you see only the stone form, either plain stone or sculpted. The eyes and face age nicely on the stone. Then, there is a ritual of a fruit-mixture bath, then a milk bath, then a honey bath and so on. Sometimes there are seven or eight steps. Once the beauty rituals are over, they drape the saree on and put on flowers. You would then return to the temple, say, around 4.30 PM, when the goddess is completely ready. By this I mean the sandalwood on the face, the jewellery, the crown, the make-up, etc. Through this layering, you may see the surface, but you also access what is beneath.

Similarly, while documenting these goddesses, I felt that some photographs had enough of a message, or of the unseen, coming through. While for others, I needed to layer the images heavily to complete them. To me this is a sort of ritual.

From the series The Kingdom of Kush. (Delphine Diallo. Image courtesy of the artist.)

K: How do history and mythology interact in The Kingdom of Kush, and how does the project use this space to explore themes of decolonising Black cultural identity?

Delphine Diallo: Cheikh Anta Diop, a Senegalese historian and anthropologist who was also a scholar of Afro-American culture, writes in his book, The African Origin of Civilization: Myth or Reality, about the Kemet civilisation that predated even the Romans and Persians. The book mentions how temples in Sudan were also flooded by the Nile. People assume the civilisation was only in Egypt, but it was also in [present-day] Sudan. And at this time, the kingdom was called Kush (2500 BCE–300 CE). After reading his work, I decided to travel to Egypt and do my own research. I wanted to use AI to bring back the image of this ancient civilisation.

Even beyond the idea of race, I think we should deconstruct ideas and find what has been hidden. I see it like putting pieces of a puzzle back in place and showing it to the viewer, and asking them what they are going to do now with this knowledge. You have to push beyond what you see, and for that there needs to be a new kind of vision or perception. We have to change the way we perceive the world in order to communicate better. The point is to gain back our humanity, to embrace our complexity but also the simplicity of being human. It can be questions of psychic, spiritual and mathematical nature, but it can also be joy, like flowing water.

From the series The Kingdom of Kush. (Delphine Diallo. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I am also obsessed with mythology and why the stories of so many women have been hidden or destroyed, like the stories of oracles, goddesses, deities, healers, etc. Ancient mothers were not born under the yoke of patriarchy. For thousands of years, Africa was ruled by a powerful order of the matriarch. Considering the current state of African women around the world today [faced with layers of patriarchy], one could hardly believe the presence of the matriarch and the enormous influence she wielded in the ancient world. These women do not bear mention in books on mythology. There is so much kept secret, but once you hear it, you will not be able to see the mother in the same way. The world wants to see us as divided; we believe we are born into this and that it has always been this way—dehumanising and patriarchal. If we believe that, we lose our freedom. So, history really is the key to perception.

From the series The Threads that Connect Us by Fotokids. (Ana Ruth Pablo. Image courtesy of the artist and Evelyn Mansilla, Fotokids.)

K: In The Threads that Connect Us, you put together an exhibit of photographs by the children enrolled in Fotokids in Guatemala. Given that the photos have a palpable sense of fantasy in them, how does this visual expression reflect the children’s sense of self-identity?

Evelyn Mansilla: Fotokids started in Guatemala City, in the city’s garbage dump. Nancy, our founder, is from the United States. She was a journalist who came here to work on an article about the people living and working in the dump. She noted that the children were fascinated by her camera, so she decided to set up something to teach the children photography. That is how Fotokids was formed, thirty-two years ago.

Now, we work in different parts of Guatemala City and in Santiago de Atlantis, which is a Mayan village. We work with children from nine to eighteen years of age. Initially, Fotokids was about teaching them photography, so they can use it to express themselves. Through the years, we decided to introduce graphic design and video too. Now, we are more like an expression programme, because we work on giving them the tools with which to express themselves, to find what they want to do and to help them to dream about the future.

I used to live next to the garbage dump, and I was enrolled in Fotokids when I was twelve. I graduated, went to university and studied journalism. Today, I am the Executive Director, and it is incredible for me to have the chance to give other kids the same kinds of opportunities I had. If you have the opportunity to believe in yourself, you think your life could change, but nobody tells you that.

From the series The Threads that Connect Us by Fotokids. (Claudia AIxbalán T. Image courtesy of the artist and Evelyn Mansilla, Fotokids.)

In The Threads that Connect Us, we see a glimpse of their daily lives. You can see how they connect their lives through the images and show the world that there is beauty around them. They want to show all the people that each life has its own story. For all our students, it is important to maintain their sense of identity, especially in the face of discrimination from people from the city and other communities. We reinforced this in each class and empower them to be proud of where they come from. I think this is why you can see that each photographer has their own style. I think one of the essential things of photography is that you can convey this.

From the series I Glitter You With My Thousand Eyes. (Radha Rathi. Image courtesy of the artist.)

To learn more about the artists and themes featured as part of the Chennai Photo Biennale this year, read Anoushka Antonnette Mathews' short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of bodies and landscapes, Kshiraja’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of landscape and history, Upasana Das’ short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of power and representation and Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with the curators of the primary shows.