Bodies and Landscapes at the Chennai Photo Biennale

At the Chennai Photo Biennale 2025, photographs become portals of possibilities as they blur the line between the subject and creator. Beyond asking “Why photograph”, we are led to the questions—“Who photographs?” and “who is photographed?” Countering mainstream and external representations of Palestinians are images created by teenage girls and boys in Gaza, produced in 2020 as part of the Eyes of Gaza exhibition curated by Cora Josting and Nahed Awwad. Agency and expression become as integral to imagemaking as playfulness and exploration. The cyanotype prints curated by Sonam Chaturvedi bring together the work of girls between the age groups of 14-18 from care homes across Delhi. Their cyanotype prints were composed around the theme of “One day I woke up as a tree!” and brought to life their internal worlds and stories. Krithika Sriram challenges the misrepresentation of Dalit bodies and female identity by using photography as an act of resistance. Bhumika Saraswati’s work questions and challenges the dominant climate change narratives of heat by looking at rage and resilience within women who belong to Adivasi and Dalit communities. Constructed images that fuse fiction and nonfiction in metaphoric realities define Sridhar Balasubramaniyam’s work. His compositions position landscapes against bodies and present multiple realities that are possible within a frame. Each of these photographic works seems to represent land and body in the context of conflict, erasure and visibility.

Anoushka Mathews (AM): Why was it important to showcase these photographs by children from Gaza? Can you talk about some of the works in the show What Makes Me Click!?

Cora Josting: The idea comes from an attempt to counter the cancelling of Palestinian voices, especially in Germany. The intention was to move away from an outsider perspective of Palestinians to representations of life from Palestine, by Palestinians. Working with children was partly influenced by the thought that it seemed impossible for people to accuse them of belonging to terrorist organisations or propagating extremist views. An insight into their worlds opens up the possibilities of viewing Palestinian life from their point of view.

Olive picking: “Olive harvest is the time where the whole family gathers to help pick the olives. All the kids, aunts and grandparents are there. I love the olive harvest because it makes me happy and I love the olive trees.” (Maram Falyouna [aged 13]. Image courtesy of the artist.)

It also allows for viewing each life as being more than just a number. The nine children whose works are curated in this collection of photographs belong to Gaza. In the workshops held with them, they were asked to use the camera to explore their favourite places, portray their friends and families and represent what they consider important about where they come from. Each group of photographs represents the title of the exhibition in that the children and their cameras become the eyes of Gaza and, through them, we are offered glimpses of Palestinian life.

Photos, Music, and the Sea: “I am the only girl in the family and the eldest. My hobbies are painting, music and acting. I like music a lot. I play guitar and the qanoon. I want to be an influencer on social media; I like to be in front of the camera. The sea is the place where I like to be the most. I wanted to show the beauty of Gaza, not only the destruction. Gaza and Gazan people are beautiful in my eyes.”( Jan Khaled [aged 16]. Image courtesy of the artist.)

The workshop included children who have never left Gaza—it is the only reality they know. Engaging with art allows them to travel to other places and allows for their photographs to capture what they see in the world around them and what they consider valuable and important.

The gaze of the Western media that limits Palestinian representation to suffering and victimhood is challenged by these photographs. The images were taken by the children in 2020, during the lockdown. Viewing these images in the context of the current violence in Gaza reminds us of how Palestinians are being robbed of the right to an ordinary life. The simple pleasures of olive picking or spending time with one’s family are transient moments in the lives of those in Gaza. This is perhaps why they were documented by the children as their photos point to the celebration of simple pleasures, family and community.

We also shared letters with parents that their children and their work were not being used for any political agenda. The copyrights remain with the children and the captions for each photograph are written by them.

My World: “My room and my paintings are my world. I spend most of my time painting on paper and on walls. The mural is my fingerprint in my home; it speaks about our other dimension in the universe. The lines are my way of describing many different emotions.” (Faheed Shahab [aged 17]. Image courtesy of the artist.)

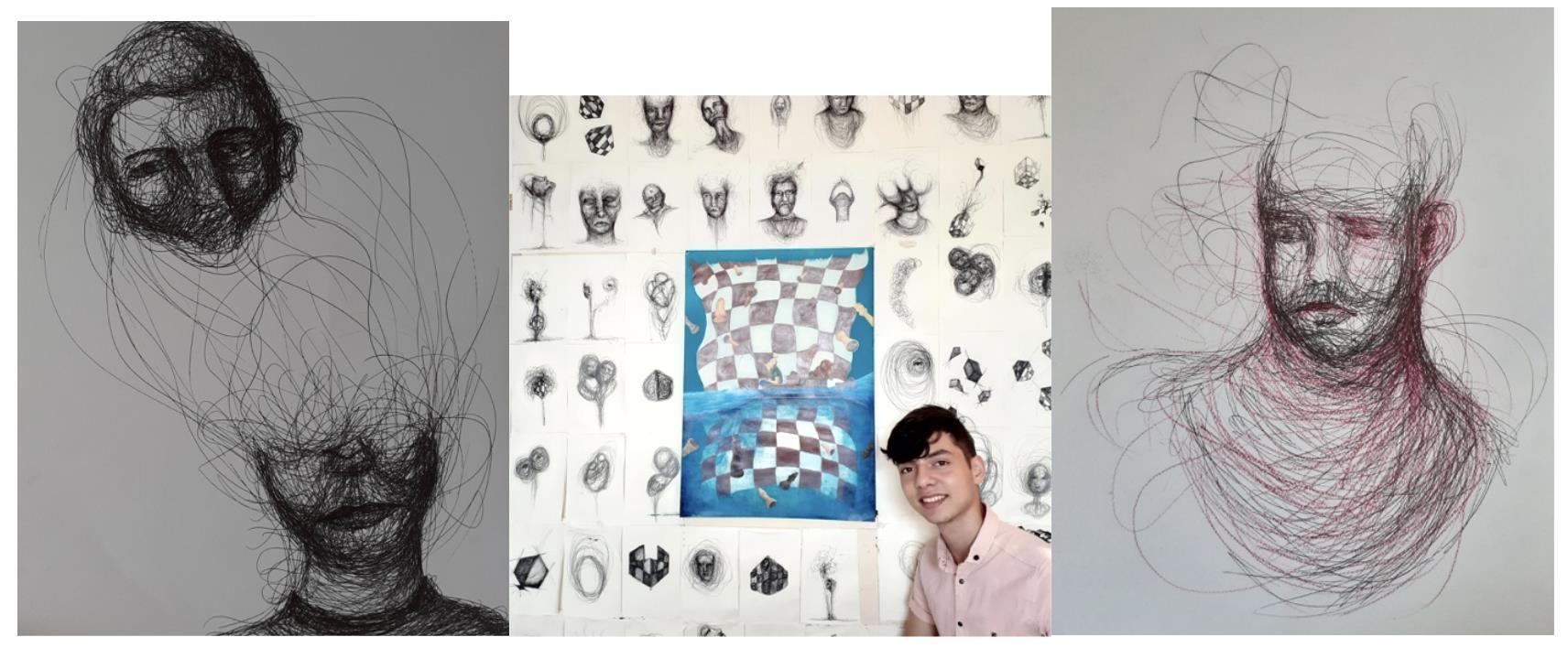

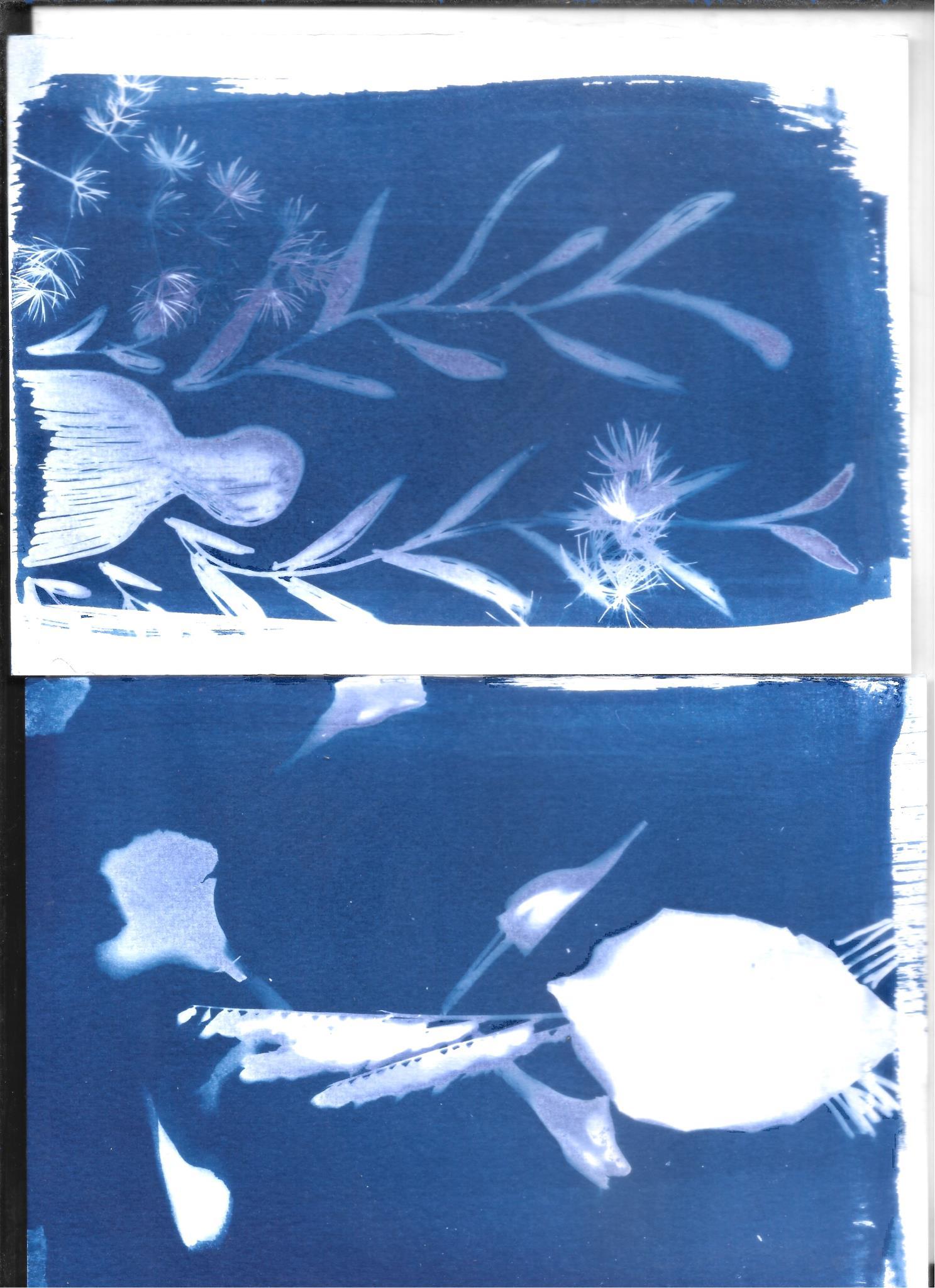

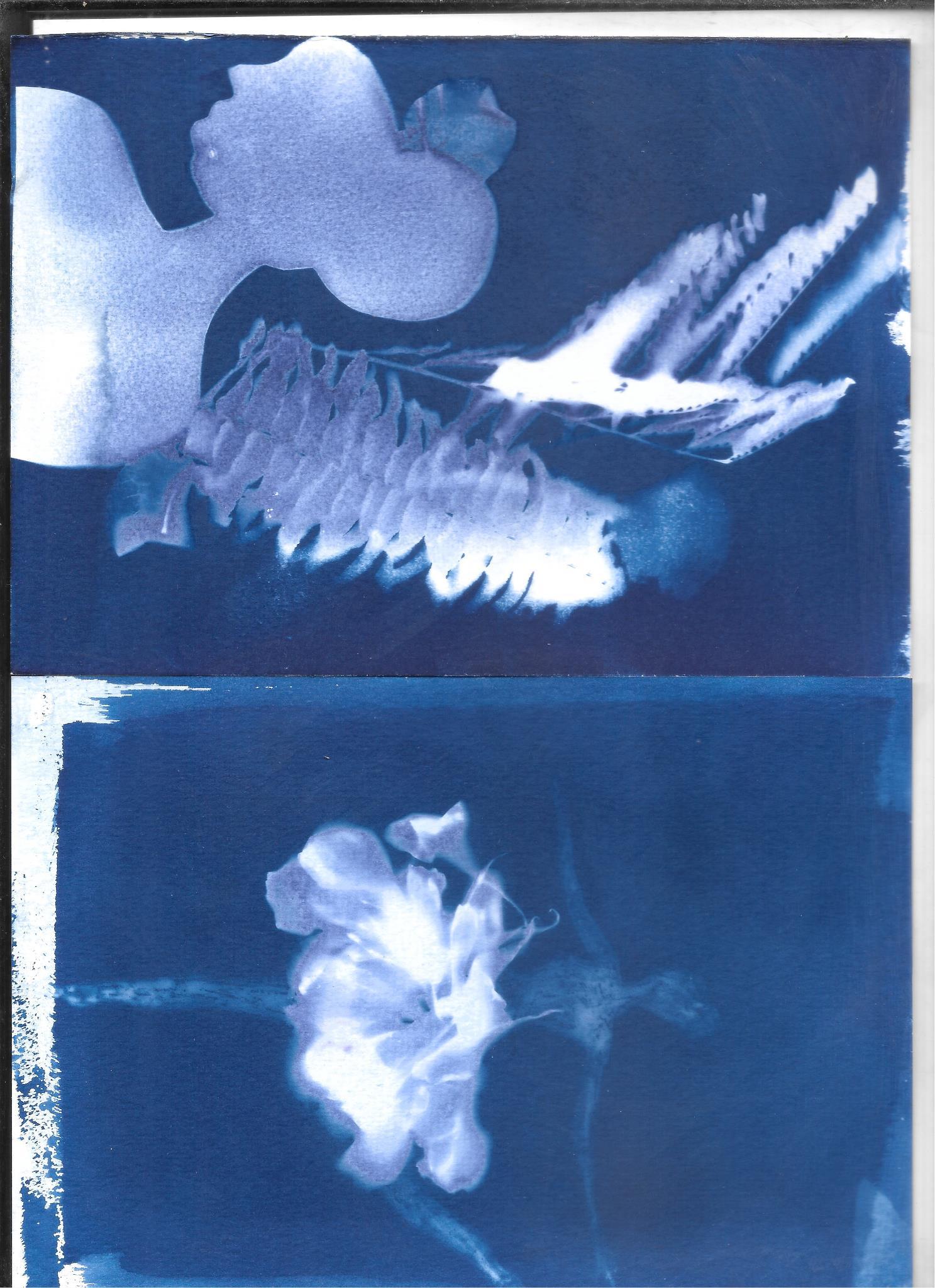

AM: Why did you choose the theme One day I woke up as a tree! for the cyanotype workshop? How did the theme allow the girls from care homes to express themselves through cyanotypes?

Sonam Chaturvedi: In my workshops with younger people, I try to push them to think through stories. So rather than just giving them a word, I find that a theme allows them to think beyond the frame and come up with narratives. Each participant was free to interpret the theme as they wished to. I think this allowed them to portray themselves in the final compositions. Not only did they have to think about the story and ideas they wanted to portray, but also the material they would use to get their message across. The use of petals, markers, OHP sheets, cut-outs and other materials provided to them showcased their creativity in imagining how these objects would block light.

Cyanotype prints on the theme “One day I woke up as a tree” by the care home girls as part of the Artreach India workshop. (Image courtesy of Sonam Chaturvedi.)

There were all kinds of themes like friendship, hobbies, emotions and desires expressed in the final cyanotype prints that the girls produced. The themes allowed for them to be free of the limitations that their own bodies are bound by, pushing their imagination of what they could do as trees. The girls came up with all kinds of trees. A tree with a crying face embedded on the bark seems to point to an internal melancholy and sadness.

Cyanotype prints on the theme “One day I woke up as a tree” by the care home girls as part of the Artreach India workshop. (Image courtesy of Sonam Chaturvedi.)

We also see trees wearing frocks, girls dancing together and tree friends hanging out. Two of the girls wished to document their friendship by showing two trees holding hands.

I found the dancing tree with a delicate ballerina made out of carefully placed petals very interesting. Trees are rooted and stuck to one spot, so imagining them as dancing seemed to point to the desire of perhaps wanting to move and be free.

Cyanotype prints on the theme “One day I woke up as a tree” by the care home girls as part of the Artreach India workshop. (Image courtesy of Sonam Chaturvedi.)

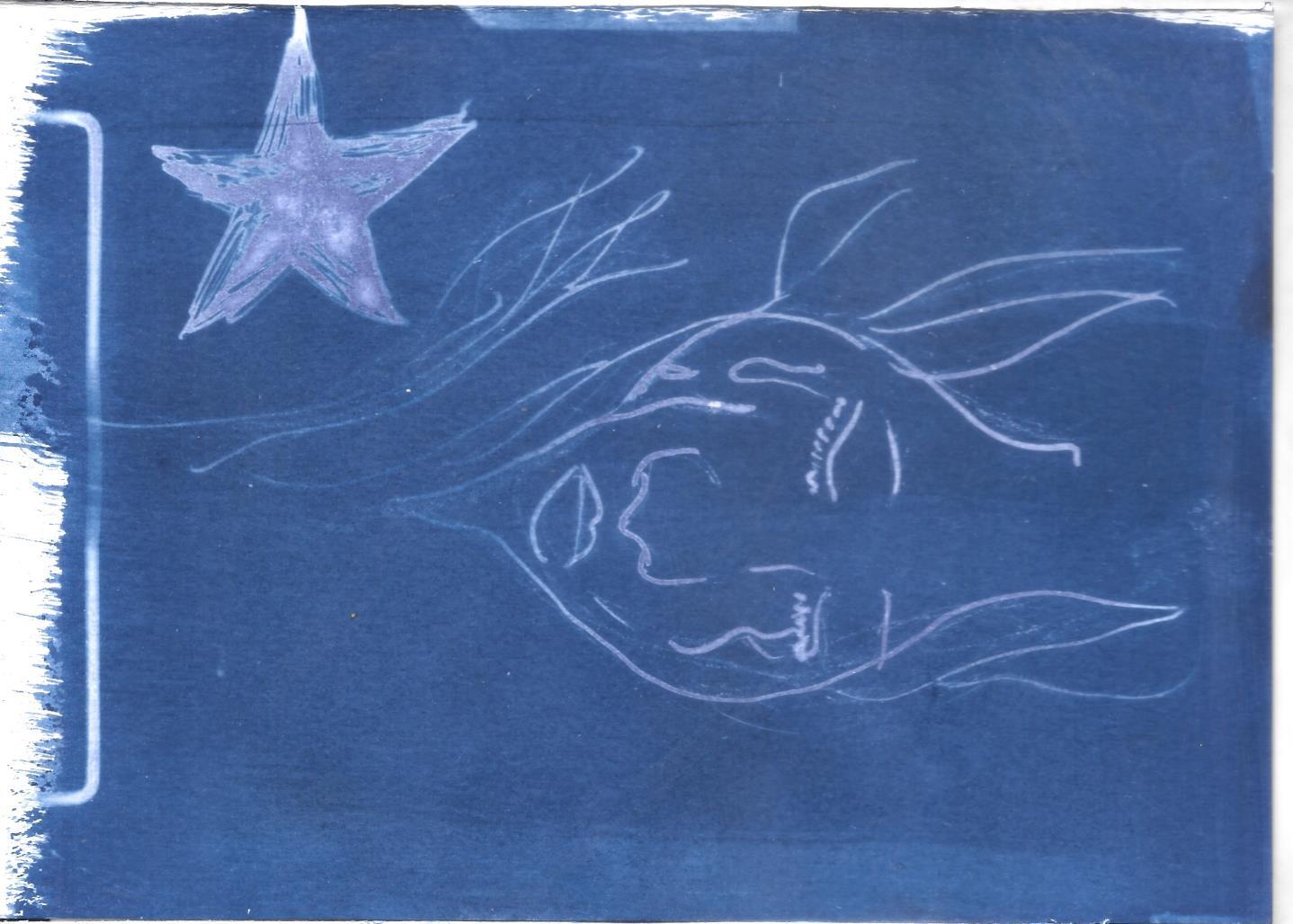

AM: How is photographing an act of resistance for you? Why did you choose to work with your mother to make these photographs? Also was there a particular reason why you chose to work with anthotypes for some of your prints?

Krithika Sriram: Photographs lend a feeling of being seen. For someone like me, who is from a community that is constantly misrepresented, the medium of photography gave me the agency to create new visuals around what Dalit identity is. It also moves beyond identities and stereotypes that are forced upon you and weigh you down. So, because my medium is photography, I use it as an act of resistance itself. I am able to create these visuals and talk about my identity and what it means to me, on my terms. You can see aspects of that in Thoothan (Messenger) as well, where you see people from the Dalit community making images of themselves, their culture and the celebration of their culture.

The process of making these images was a meditative journey. Central to the entire intention of all of my works is mainly Dalit representation. Staging images was an act of acknowledgement and a celebration of our identity.

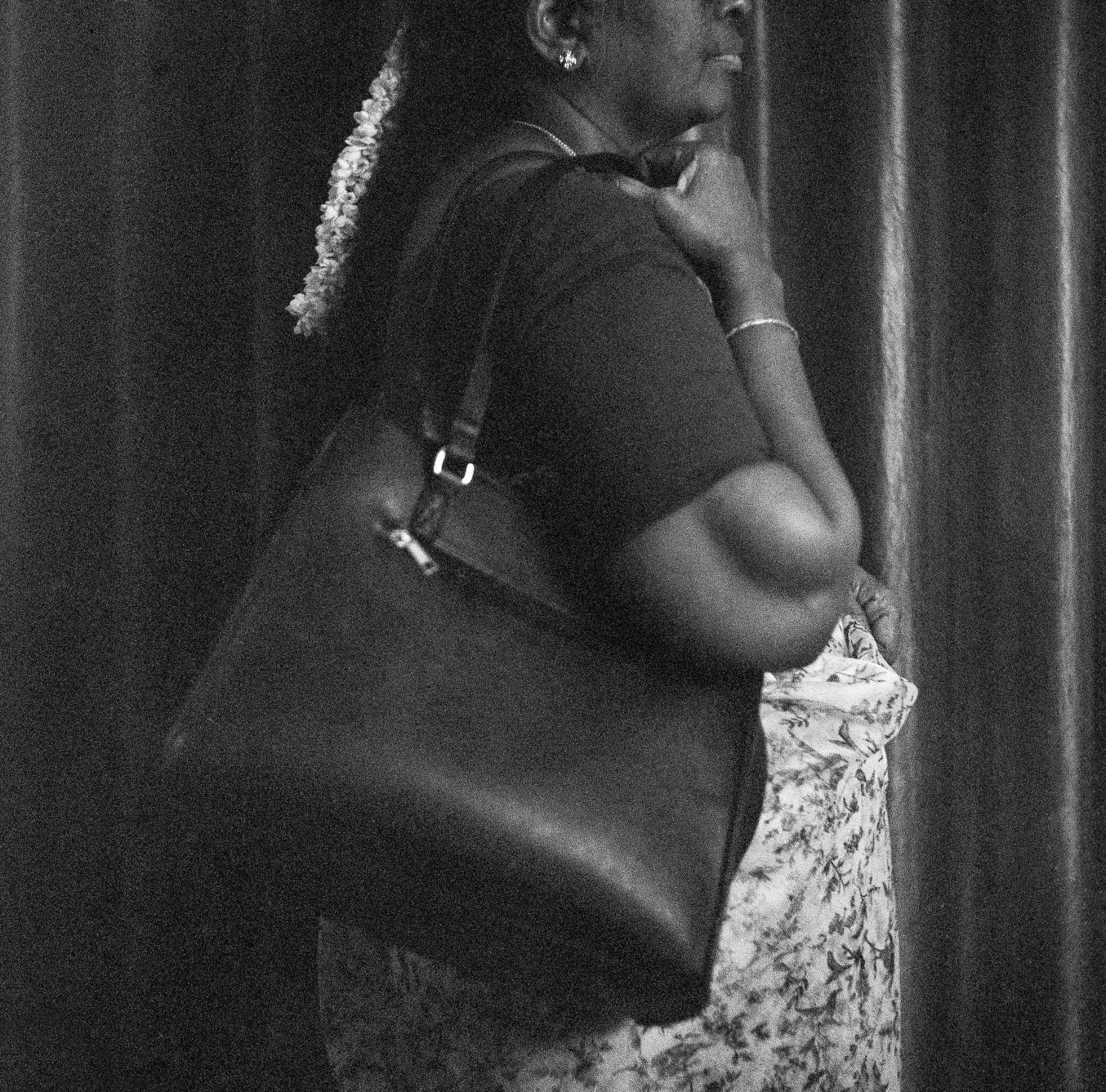

Amma with her Office Handbag, Home. (Krithika Sriram. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Karukku: An Autobiography by Bama, exploring her Tamil, Dalit and Christian identity, greatly inspired me and, in part, my work responds to it. Karukku, for me, is as much about Dalit communities and personal relationships as it is about the female experience of being Dalit. The stories, characters and instances from Karukku remind me of my home and my people. And so I wanted to respond to that. I think it was an automatic thing to work with my mum because so much of the writing reminds me of her and her mother. And so that is the reason I worked with my mother. I also felt like it was important to pair up the photographs with the text from Karukku because it is so powerful.

Amma and Me, Home. ( Krithika Sriram. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Choosing to work with anthotypes—images created using photosensitive material from plants—came from wanting to work with flowers which were once banned for Dalit females in Tamil Nadu. Controlling the female body and sexuality is central to caste oppression. In using flower pigments to depict my own body, I wish to take the control back. Through my work, I want to talk about my community identity as well as personal identity. The fading anthotypes mirror the transient acknowledgement afforded to the Dalit female, whose plight at the bottom of the Hindu-Indian social order is either conveniently forgotten or willfully ignored. These prints, with their gradual fade into obscurity, parallel the persistent erasure of the Dalit female narrative from the collective consciousness.

Anthotypes using Rose pigment documenting Dalit female bodies. (Krithika Sriram. Image courtesy of the artist.)

AM: How do you use heat as a metaphor to talk about gender, caste and the climate crisis? How does your work counter current mainstream climate discourse in the context of different forms of marginalisation?

Bhumika Saraswati: I started doing this work when the conversation about heat waves was not as intense as it is today. But in the past year there have been a lot of articles, especially peaking around June, where we hear of rising temperatures. Article after article talks about the number of people who died due to heat—112 people, 117 people, etc. Something about that did not sit right with me. As a trained journalist, I could not help but ask the question—who were these 117 people? Why did these 117 people die of heat? And why is the fact that these were preventable deaths not talked about?

Every year again during peak summer, we see these utterly dehumanising visuals of people suffering because of the heat and rising temperatures. These visuals have a very predominantly male, upper-caste gaze—a saviour gaze. I find such images very extractive. The entire conversation in the climate circle talks about how it impacts vulnerable and marginalised communities. But who are these communities? Why are we not naming them or addressing them? So, I find this sort of climate discourse very brahminical in its own way, and it is violent. That violence directly and indirectly ends up on our bodies.

From the series Unequal Heat. (Bhumika Saraswati. Image courtesy of the artist.)

It made me think about how heat is not just about rising temperatures. So there is a visual where a woman is wearing winter gloves in 50 degree Celsius to protect herself from wheat husk. She is wearing traditional clothes, and on top of that, to protect herself, a full shirt—probably a husband's worn-out shirt. These layers of clothing reveal patriarchy; they reveal the caste dynamics of this country, which reveals the broken structures that oppress people. The existing structures of caste and patriarchy greatly contribute to this crisis and that is why it is an unequal heat. And it is also linked to an internal rage which lives inside of us, all of the time. I wanted to document this rage that coexists with resilience.

From the series Unequal Heat. (Bhumika Saraswati. Image courtesy of the artist.)

While I was documenting all of this, I was also speaking to doctors. I learned that women who work outdoors do not drink enough water, because they do not have safe spaces to urinate. These communities have survived oppression and yet their resilience remains undocumented even in the face of all this adversity. These are amazing women who do not even own land, but work as farm labourers. I was interested in establishing their relationship with land and creating visual evidence of their work and lived experiences.

I personally feel a lot of it works as evidence or evidential imagery. Why have we not looked at resilient communities, who are at the forefront of the climate crisis? I think it is supremely important to counter the mainstream media climate crisis narrative because constantly reading that 117 people have died of heat without knowing who these people are leaves us at the risk of becoming desensitised. And, you know, what can be worse?

From the series Unequal Heat. (Bhumika Saraswati. Image courtesy of the artist.)

AM: What is your process behind constructing images that combine both documentary and fiction? How do people and land feature in your images and the compositions?

Sridhar Balasubramaniyam: I travel a lot across South India, shooting closely with people, nature, culture and landscapes. Along the way, I notice certain visuals that strike me as metaphors which I am unable to capture in the moment. But those metaphors stay with me and I use them later in images that I make by reconstructing those moments with actors. I like to combine these metaphors that are rooted in reality and construct images that combine the real and planned.

I write my images almost as if I am writing out a scene, this is possible because of my background in theatre. I evolve the text for the image almost like a script. I recce the landscapes, reach out to friends or theatre artists and evolve my idea until I am ready to construct that image. I only take pictures once I am familiar with the place and people. Creating constructed portraits requires trust and my repeated visits and interactions allow for people to become comfortable enough for me to photograph them. I find that to be a very beautiful thing.

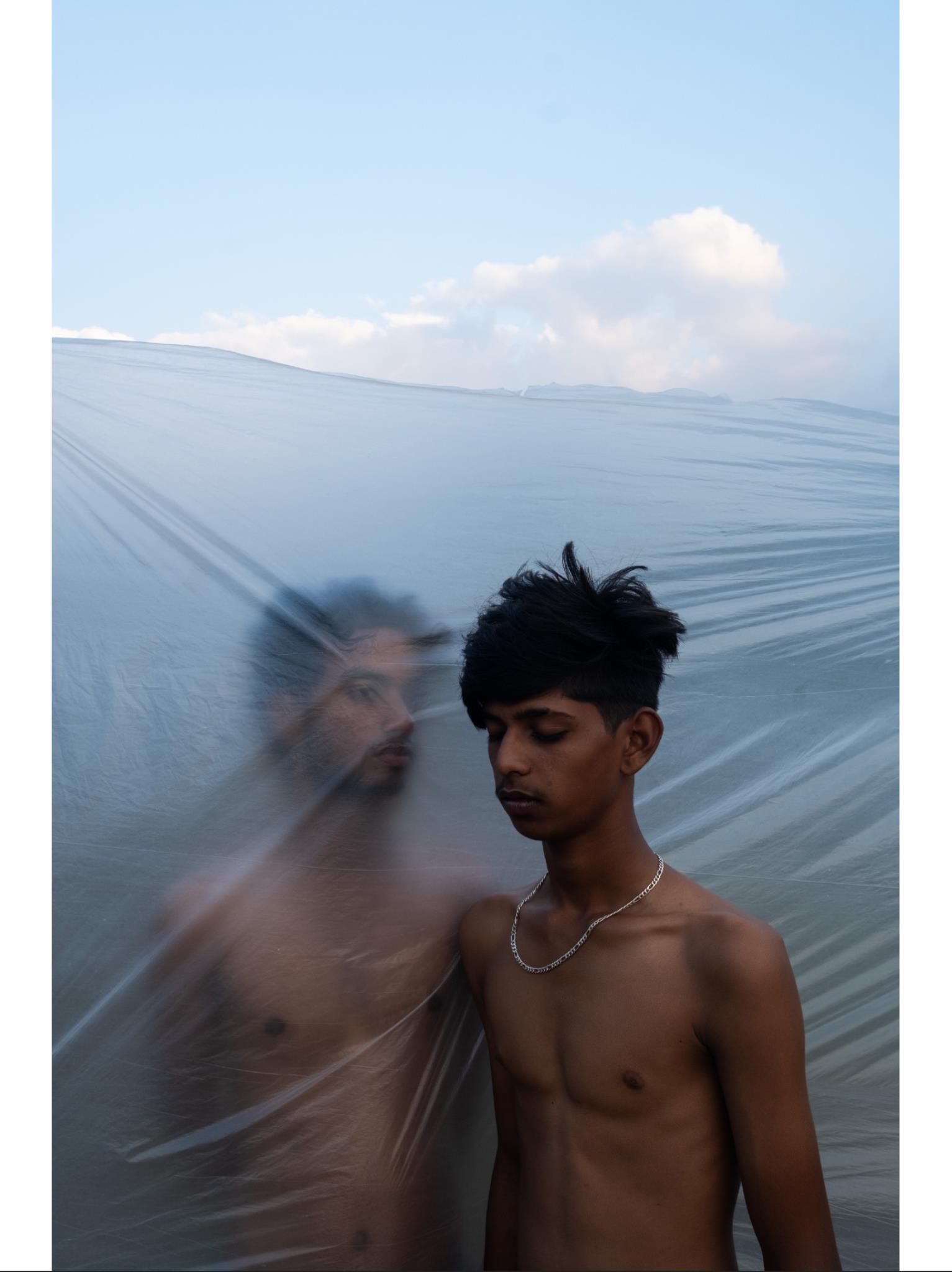

From the series Manarsuzhal. (Sridhar Balasubramaniyam. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I also use an object only if it has meaning. For me, the mirror captures everything—from the sea and the stars to faces and landscapes—but it reflects light. I find that idea interesting and so I like using mirrors.

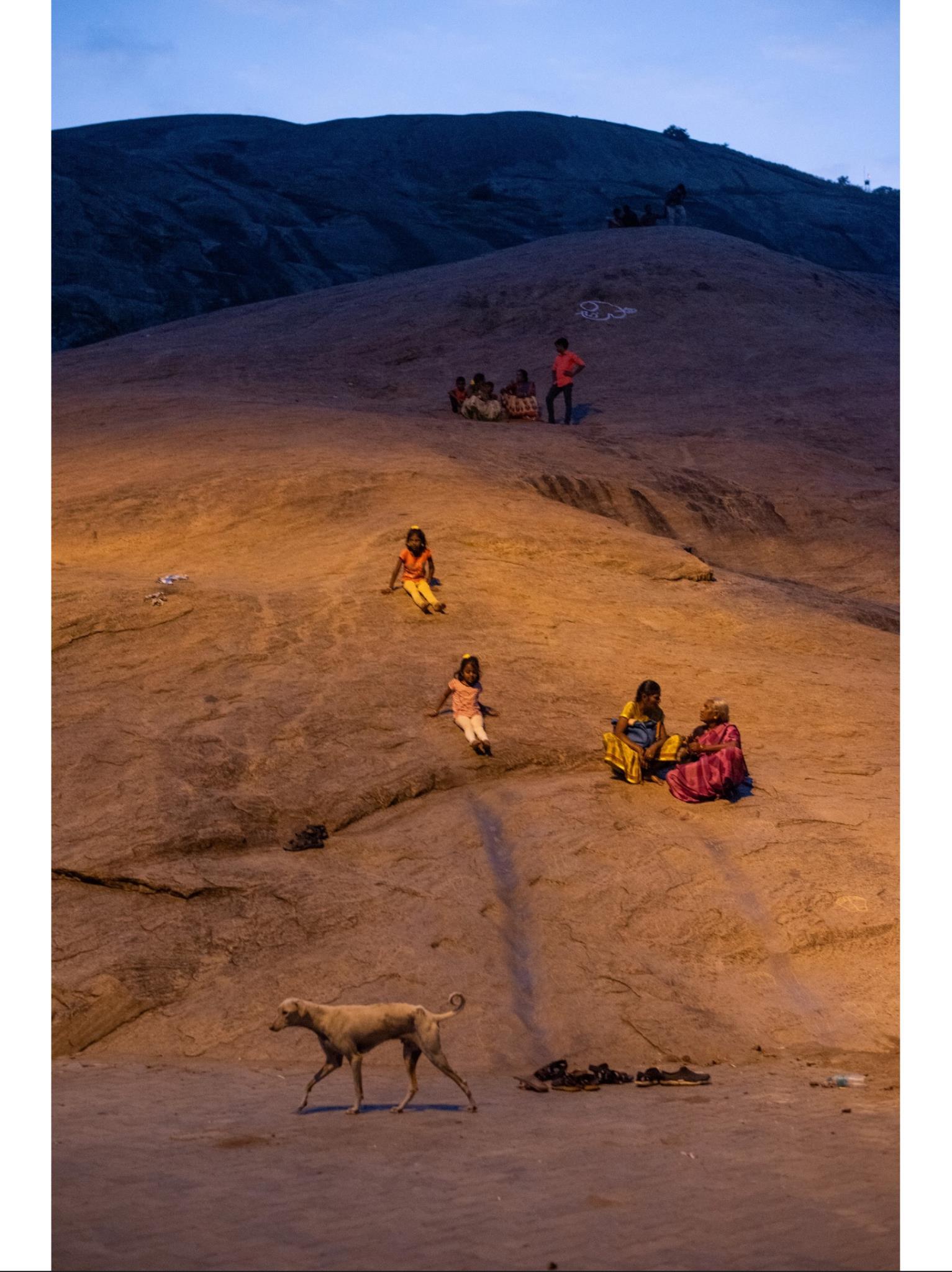

From the series Manarsuzhal. (Sridhar Balasubramaniyam. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Manarsuzhal translates to “migration of sand.” I am constantly on the go, like sand, and as I move, I absorb and reflect on everything that I see around me. I find meaning in the mundaneness of everyday life and I like to play with juxtaposing multiple realities through my photographs. I am interested in the interplay of motion and stillness, both in bodies and in landscapes. Revisiting the same landscapes over the years helps me to understand impermanence and study change and evolution, which further informs my practice and exploration.

From the series Manarsuzhal. (Sridhar Balasubramaniyam. Image courtesy of the artist.)

To learn more about the artists and themes featured as part of the Chennai Photo Biennale this year, read Kshiraja’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of landscape and history, Upasana Das’ short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of power and representation and Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with the curators of the primary shows.