Archives of Our Own: Studying the Family Photograph in India

I have often found it fiendishly satisfying, introspective and—admittedly—voyeuristic, to immerse myself in the palaver that accompanies the act of taking a group photograph. It is a choreography that brokers five seconds of peace for the perfect portrait: the awkward hesitation before stepping in front of the camera; posing, but not posturing; the indecision which comes with placing your hands; the interminably long moment where your smile starts hurting; and more often than not, the inevitable groan that is collectively felt when the photographer asks for another picture. The result of such an elaborate dance, however brief, readies the entire ensemble for what Henri Cartier-Bresson called “the decisive moment”, that transcendental instant where every motion, every action and every breath comes together before dissolving into laughter, exhaustion and dispersal. And as the editors and authors of Zubaan Books’ latest publication, Framing Portraits, Binding Albums: Family Photographs in India (2025), stood for their photograph at the recently held book launch at India International Centre, Delhi, I was curiously reminded of another photograph—a family photograph, no less—from 1987, shot at Suresh Punjabi’s Studio Suhag in Nagda, Madhya Pradesh.

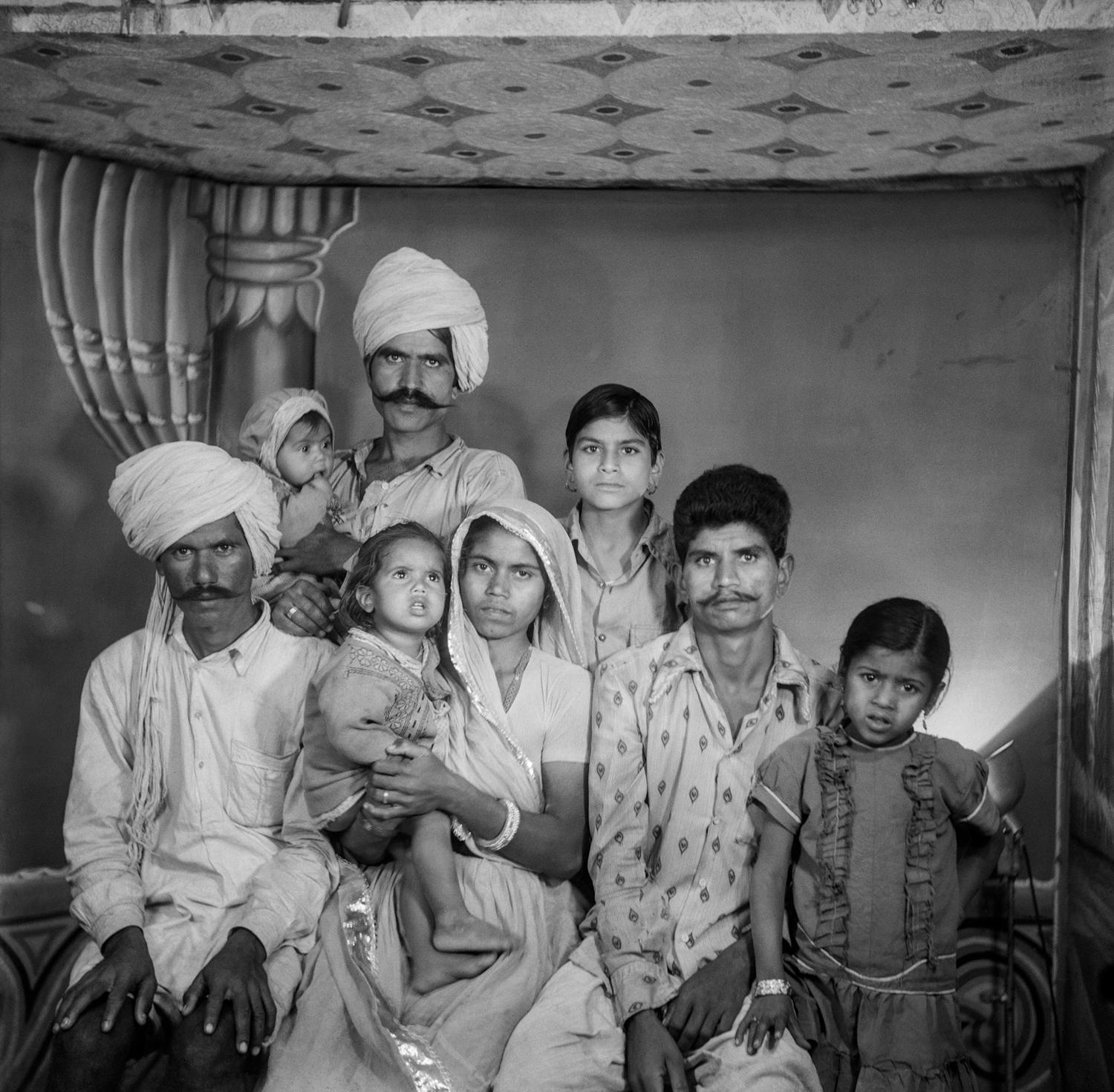

“Untitled (Group Portrait of a Family)” (Suresh Punjabi. Nagda, 1987. Celluloid negative. Image courtesy of the Museum of Art and Photography.)

In the alchemical composition of the celluloid is a family of eight members, their gaze piercingly held in front of the camera. “Untitled (Group Portrait of a Family)” stages itself—literally, with an elaborate backdrop, spotlights and fanciful clothing—with slight unease; simmering underneath the surface, the viewer is greeted with fascination as well as anxiety: Who are these people, and what was on their mind when the flash went off? More importantly, where are they today? In its rather esoteric mythology, Punjabi’s photograph has suspended a moment in time where the family is the subject of our attention, as well as the object for the camera. For Roland Barthes, this essence, or noeme of photography, is its ability to take something real, and make it “it-has-been”; an immobility that memorialises the moment captured for posterity. The picture lives on, even if the people do not. Perhaps this is why I remembered Punjabi’s photograph—capturing the jubilant celebration of launching Framing Portraits, the camera objectified the event; its result, a certainty of existence, flattening the moment in time and abstracting its reality. It was death, sublimated; the group photograph, much like Punjabi’s picture, memento mori. This is what makes Shilpi Goswami and Suryanandini Narain’s editorial enquiry in Framing Portraits highly relevant, for it is an enquiry that attempts to understand the family photograph in the Indian context beyond its im/mortal experience—an attempt that discursively challenges such photographs as fixed, ephemeral blots on the canvas of family histories.

The authors, editors and other contributors at the launch of the book. (New Delhi, 6 January 2025. Image courtesy of Zubaan Books.)

“We did not define what was meant by ‘family’”, echoed Goswami and Narain in conversation with Malavika Karlekar, “acknowledging the difficulty and impracticality in defining someone else’s understanding of what family means to them.” For the uniquely challenging proposition Framing Portraits responds to, Goswami and Narain’s editorial approach—sharply probed by Karlekar for more than an hour—is equally impressive. By drawing out narratives that incisively understand the closely-guarded privations family photographs are, the anthology makes itself clear by defining what it is not: a comprehensive survey of all types of family photographs in India. By rescuing itself from this quagmire of ambition, it seeks instead to survey the intersections that inform family photographs, as particular areas of interest focused upon by the contributing authors. To that end, the essays are organised into eight categories (an organisation that is in no way exclusive, allowing for multiple overlaps) that touch upon intergenerational dialogues, migration and the diaspora, sexuality, archival excavations, class and caste hierarchies, ethnic margins, materiality and positions of the State.

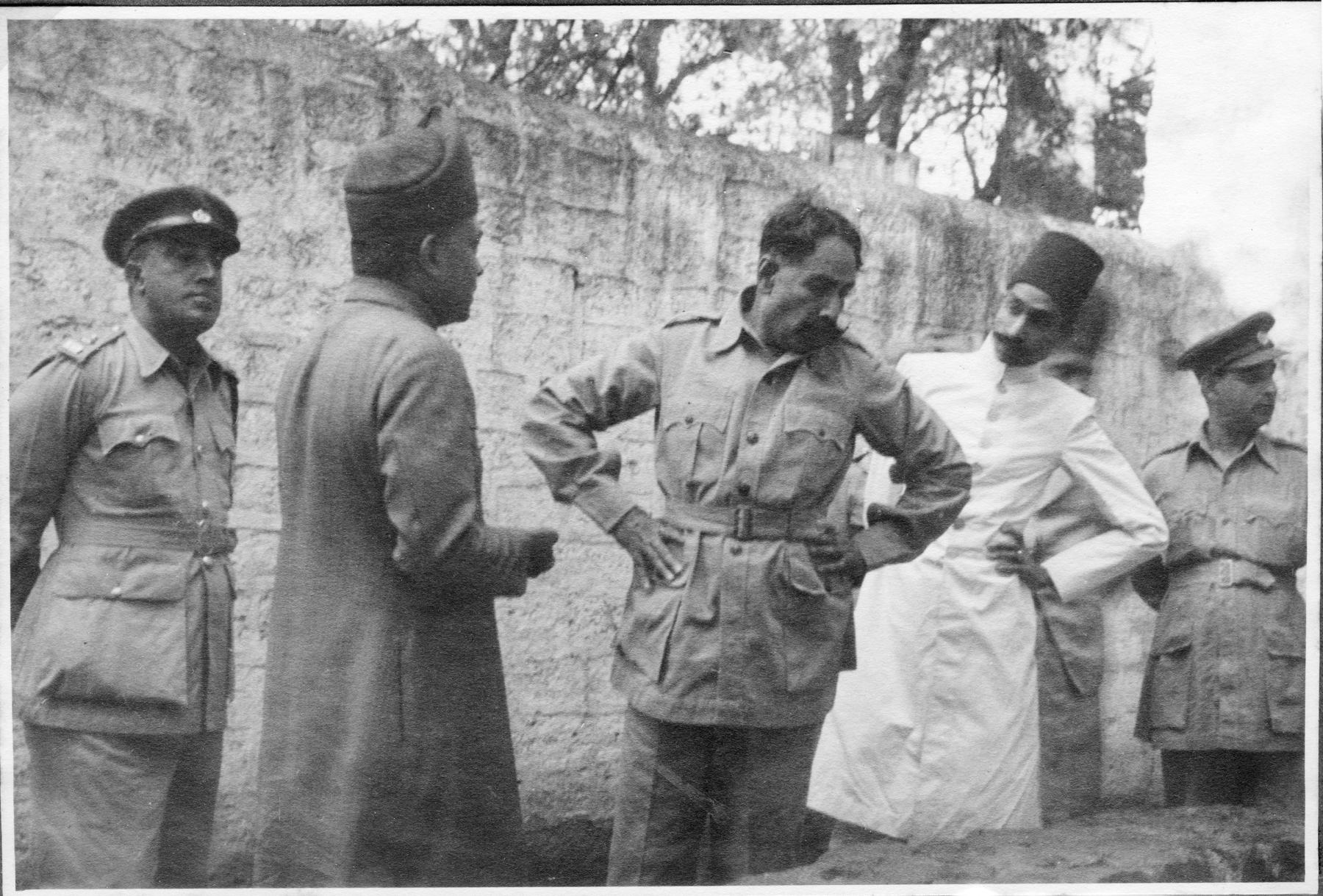

Mohammad Ahmed Said Khan on an official tour along with his son Ibne Said Khan. (Unknown photographer. Bidar, 1940s. From the Private collection of Mohammad Ahmed Said Khan. Image courtesy of Nawab Ibne Said Khan/ Aligarh Photo Archive. Featured in Uzma Mohsin’s essay, “Snapshot of a Modernist Muslim Imagination: The Aligarh Photo Archive.”)

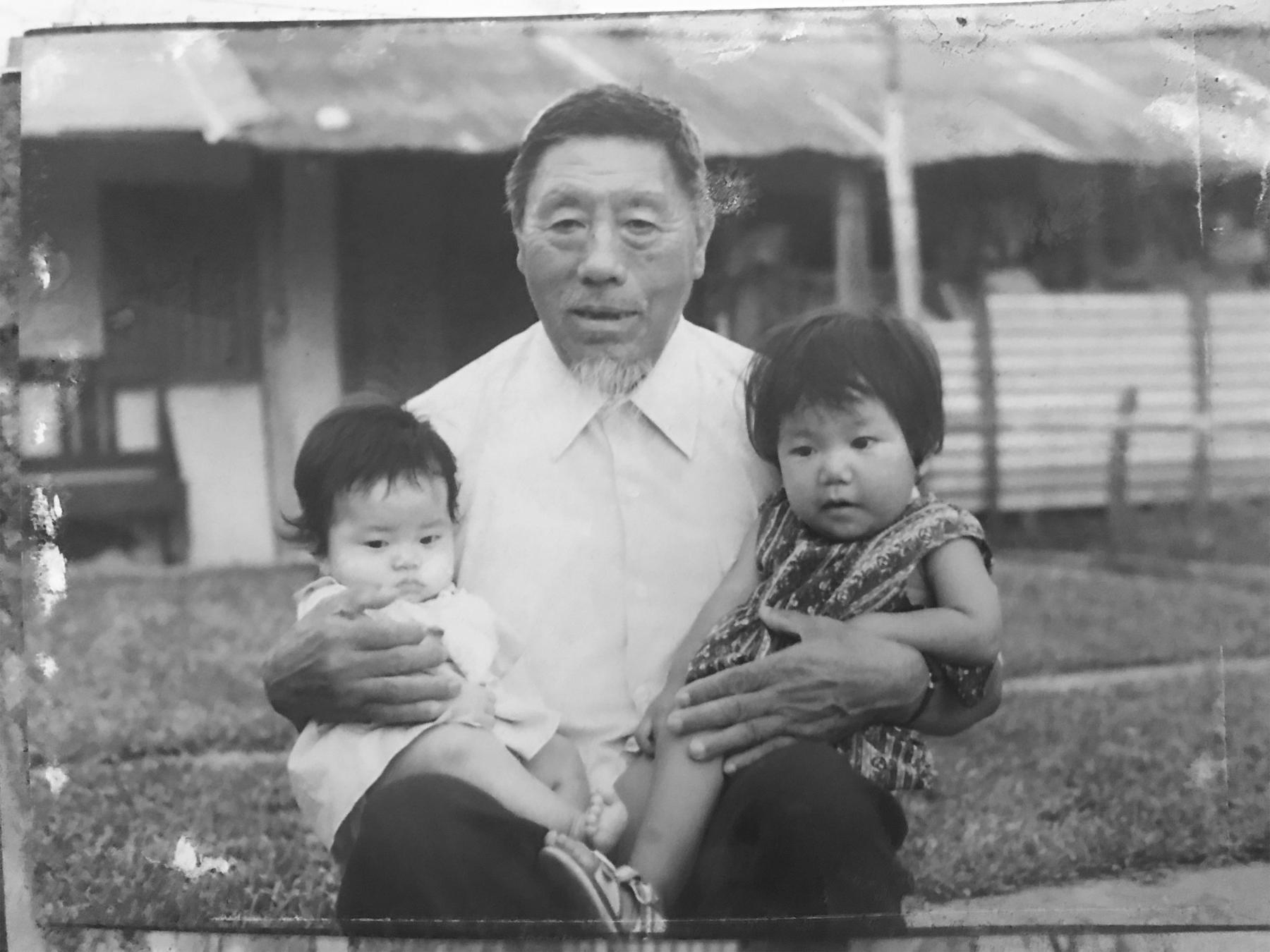

Phousabou Charenmei with his granddaughters Agimanailiu on his right and Sireiliu on his left. (Imphal, 1997. Featured in Anna Sireilliu Charenmie’s essay, “‘Ake nde nai tadno?’ A Naga Perspective on Collective Forgetting and Remembering: The Great June Uprising of 2001.”)

Ironically, it is in this very openness that Goswami and Narain’s editorial oversight is made acutely precise. The eight categories index the anthology with particular verbs prefixed with ‘re-’: (re)imagined, (re)located, (re)gendered, (re)invoked, (re)calibrated, (re)centred, (re)visited and (re)articulated. This is a powerful—if not slightly errant—indexing, where ‘re-’ sets itself apart from other prefixes such as ‘de-’ or ‘un-’. It is in the fact that ‘re-’ does not presuppose an academic discourse, a critical methodology; rather in its double meaning of ‘back’ and ‘again’, it allows the editors to generate an unpredictability that unsettles established conventions, re(!)valuating academic approaches to photography and familial histories. The introduction to the book notes this lucidly: “...to these possibilities of ‘identification’ and even ‘misidentification’, our contributors have engaged with the process of textualizing family photographic narratives in unusual and experimental ways.” ‘Re-’ here instigates a break from linearity, signalling towards the complexities that define the placement (and movement) of family photographs across time and space. Arguably, this is Framing Portraits, Binding Albums’ central tenet, attempting to unframe and unbind the family photograph from a space of neglect, recentring its historical and innately personal presence in an emerging discursive space.

From the series Eat with Great Delight by Rajyashri Goody. (Featured in Jaisingh Nageswaran and Rajyashri Goody’s essay, “When I Start Photography, I Start with My Family.”)

Faredoon at the cemetery, 1960. (Featured in Nadia Nooreyezdan’s essay "Ghosts in the Mirror: Unearthing the Family Archive, Renegotiating Collective Memory.")

Throughout the evening, Karlekar remained trenchant in puncturing the discussion with several questions. Most astute of these were the suppositions around gaze, anchoring our reading of Framing Portraits: Why are the majority of contributors women? Often seen as the ‘keepers’ of family photographs, are women more likely to study such photographs than men? Moreover, is gaze generational? How would a child’s understanding differ from a parent or a grandparent’s study of a family photograph?

Rabindranath Tagore with his family members. (Unknown artist. 19th century. Image courtesy of Victoria Memorial Hall, Kolkata Collection. Featured in Divya Gauri’s essay, “Framing Domestic Servitude: The Politics of Visibility in Family Photographs.”)

Towards the end of the discussion, a sobering metaphor emerged: “Family photographs have always been thought of as field notes; they inform the research, but seldom feature in it.” As Karlekar’s voice settled around the seminar hall with a restive sigh, my gaze was directed to the cover of the book, with Nony Singh’s photograph of her daughter, Dayanita, playing with her grandmother. In studying the two figures, their distinct faces, the naivete and innocence with which they rested against each other, and their untenably kind expression, there emerges a new truth: the photograph is no longer a subliminal murder or a “frightened time” but an irretrievable, bittersweet hallucination—an act of grace that can no longer be perceived, but felt, for it has been. With twenty-one essays, this is what Framing Portraits, Binding Albums does best: it rescues the family photograph from abstraction or from becoming a reduced sign and reveals its unique reality.

(From left) Shilpi Goswami, Suryanandini Narain and Malavika Karlekar in conversation at the event. (New Delhi, 6 January 2025. Image courtesy of Zubaan Books.)

To learn more about family photographs, view Sukanya Deb's curated album reflecting on the life of Parijat, a renowned literary and cultural figure, and her home, which became the centre of Kathmandu’s intellectual and cultural life in the 1960s and beyond. Also read Ankan Kazi's essay on the family albums of scholar Sohail Akbar and Annalisa Mansukhani's reflection on Cheryl Mukherji's The Last Time (2020).