On Power and Representation at the Chennai Photo Biennale

Asking artists and curators ‘Why Photograph?’, this year’s Chennai Photo Biennale (CPB) pulls us towards the basic instinct to document and respond to everything around us. Artists like Priyadarshini Ravichandran, exhibiting as part of a group of artists exploring Tamil identity, expose gender-based violence in South India, while Hannah Cooke confronts Marina Abramović and Tracey Emin, questioning their hegemonic discourse of whether an artist should allow herself to become a mother. Young learners at Photoworks UK, in turn, confront Rembrandt’s self-fashioning portraiture and take that ahead to their own self-presentations before a camera. Exhibiting in a country where colonial powers documented the landscape and its people through painting and the camera, Prarthana Singh moves to create relationships beyond the camera and explore portraiture as a space for self-presentation, particularly by women.

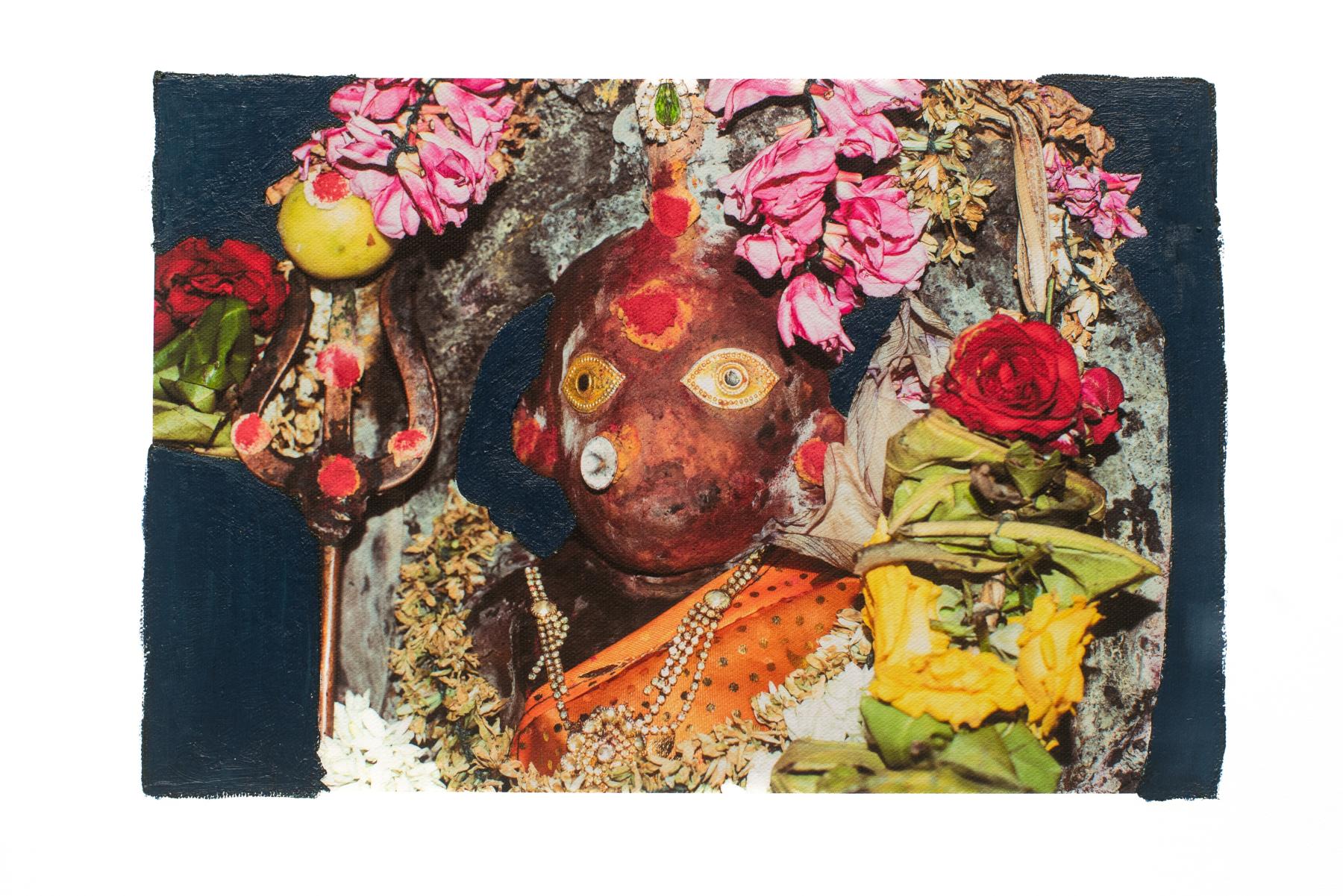

From the series Sudaroli (Priyadarshini Ravichandran. 2022-24. Acrylic on pigment print. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Upasana Das (UD): What moved you to create the works “Ada vs Emin” and “Ada vs Abramović” (2018)? Why were you referencing these two works in particular of the respective artists? And how do you see the works delving into questions of power and representation?

Hannah Cooke: I created the video works in direct response to statements Marina Abramović and Tracey Emin made about motherhood and artistic success—specifically Abramović’s claim that women fail in art because they “won’t sacrifice love, children, and family,” and Emin’s belief that she had to be either “100 percent artist or 100 percent mother.” I found these comments deeply troubling. By inserting myself and my daughter Ada into their iconic works—“My Bed” (1998) and “The Artist Is Present” (2010)—I wanted to challenge the notion that motherhood and a serious art practice are incompatible by showing that an artistic career and caregiving can exist side by side.

In “Ada vs. Abramović”, the act of looking directly at Marina Abramović creates an intimate and performative dialogue between two individuals. It is a moment of focused presence and mutual observation, reflecting the intensity of her original work, “The Artist is Present.” This gaze symbolises a direct engagement with Abramović’s legacy and her exploration of endurance, power and connection. My daughter Ada’s presence, however, subverts the controlled nature of the original performance, introducing unpredictability and playfulness, which challenges traditional notions of presence and focus.

"Ada vs. Abramović" (2018. © Hannah Cooke & VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2025.)

In contrast, in “Ada vs. Emin”, I look directly into the camera, addressing the viewer in a way that is confrontational yet intimate. This act transforms the observer into an active participant, compelling them to reflect on their own role in interpreting the work. Together, these two modes of looking explore the dynamics of power and representation differently: one through a direct, interpersonal connection and the other through a bold, outward confrontation. Both acts, however, are about reclaiming space—whether through dialogue with another artist or through directly engaging with the viewer—and questioning the roles we assign to women, mothers and artists within the structures of art and society.

By questioning traditional notions of artistic genius and authority, I aim to deconstruct the power structures that uphold certain individuals as exceptional or untouchable within the art world. Through themes of motherhood, identity, and presence, I examine how power is often linked to control over who is seen, heard and represented in art. These structures dictate who is allowed to define artistic value and whose narratives are considered worthy of attention. By challenging these norms, my work seeks to disrupt the status quo, creating space for those traditionally marginalised to reshape the conversation and assert their own presence within the art world.

"Ada vs. Emin" (2018. © Hannah Cooke & VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2025.)

UD: How did you subvert power entrenched in traditional paintings in these photographs? In what ways does the series of images present an alternate version of postcolonial Tamil identity and represent gender-based violence as the curatorial note suggests?

Priyadarshini Ravichandran: While I was researching visual histories of gender representation in South India, I found the Thanjavur and Mysore schools of paintings to be the most revered and placed in prominent places. But the subject matter in these paintings was exclusively reserved for gods, goddesses, royalty and saints. Characterised by simple compositions, the main deity is placed in the centre of the image. An architecturally delineated space is created around the portrait with rich, flat paints to mimic a mantapa or sanctum. This iconic way of defining space instinctively stuck to me as the most appropriate way to tell these layered, silenced stories of womanhood. I began to paint altars with thick paints on my photographs, not to fulfill an aesthetic function but to bring dignity and sacredness to these women protagonists who are balancing everything around them even when it is all falling apart. For me, the subversion comes in by bringing these everyday, uneasy struggles to become the subject of our complete attention.

This work is provoked by and is in dialogue with research findings to bring to the surface practices of struggle and survival which are typically kept silent or invisible. The research, titled “Surviving Violence: Everyday Resilience and Gender Justice in Rural-Urban India”, addresses the subtleties of psychological, social and economic violence inflicted upon women and marginalised genders, as well as stories of their resilience. I worked alongside the researchers to create a repository of images to express what the words cannot. All the stories they shared—their anger, fears, empathy and conviction towards the need for action—and the deeper understanding about the non-linear nature of gendered violence shaped the way I saw and photographed. Through workshops and detailed conversations, I came to understand that most women have no language to express or even recognise that what was happening to them was an injustice. And the articulation of our experience was key to working towards building a new life for ourselves. This report was published in 2023 and included my photographs.

For this biennale, I am showing eleven photo-paintings, which are part of a larger body of work. Some are very large in size to address the ‘elephant in the room’—namely the nature of gendered violence—and some are miniature to nudge us to look closer to see the invisible and hear what is unsaid. Sudaroli attempts to find a visual language, to a deep rooted battle for dignity and self-respect, becoming sparks for newer conversations. It acts as a reminder to confront the uneasy and stand up to claim power in compassionate ways. It seeks to tap into the power of images, to possibly go where words cannot enter—into core sensations or feelings and experiences of the body—and to somehow get into the skin of the issue. Initially, I thought it was not my story to tell, but as a woman growing up in our society, we have all seen, felt and experienced violence to our bodies and minds in varying frequencies. It is through the telling of stories of others that we are sometimes able to articulate our own.

From the series Sudaroli (Priyadarshini Ravichandran. 2022-24. Acrylic on pigment print. Image courtesy of the artist.)

UD: What relationship do you have with portraiture and what made you choose it as your medium? How do you document resistance with portraiture?

Prarthana Singh: I was drawn to portraiture quite early on when I got into photography. I am essentially interested in telling human-centric stories and obviously then portraiture becomes a very important part of that. I often speak about how I hope that my work can go beyond the act of image-making and transcend into more of a communal practice, in a way wherein I continue to build relationships with those who I am photographing. Making an image of somebody is a very intimate act. And I think that intimacy—that sense of choir and this kind of interpersonal exchange without exchanging any words—often comes through within a photograph. So building on those relationships in my work comes from a very emotional space and I also try to keep those emotions intact within a portrait.

I have been able to work a lot with women and I think there is a shared understanding about navigating the world as a woman. Whether it is my work with Shaheen Bagh or Champion, the work that I have at CPB, I am very drawn to telling female-centric stories of empowerment and looking for newer ways to do that. I was thinking about softer ways of approaching portraiture, which is usually associated with the idea of the power being in the hand of the person who has the camera. And for me, even when I was making the Shaheen Bagh work—where we set up a makeshift photo studio, where we did an exchange with polaroids, where the young girls who were with me were also making photos—all of that was because I am not somebody who is interested in holding on to that power that comes with the camera.

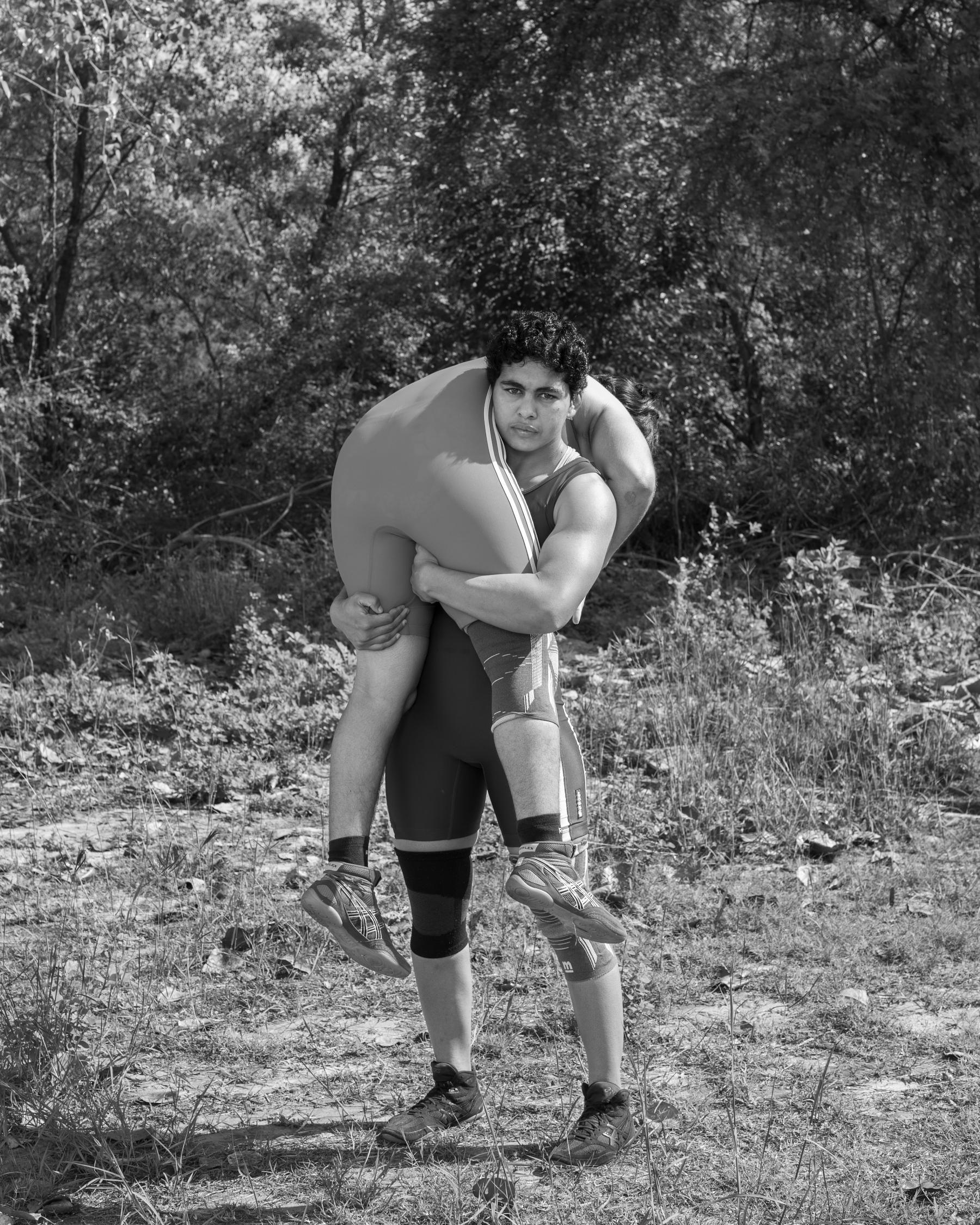

From the series Champion (Prarthana Singh. 2015-ongoing. Image courtesy of the artist.)

When we are in front of the camera or somebody is photographing us, we are able to think about how we would like to present ourselves. But often, as women, we are not thinking about that because we have been told that we should not be thinking about that. Rather that our bodies and ourselves are just there because society tells us how we should present ourselves. And so when we make an image or when I am at the camps with the women, I would ask them how they would like to be photographed. Sometimes they like to be photographed with their partner. Wrestling and boxing are both power play sports where the sport is with another person. So often they would like to be photographed with a partner or a friend or wearing the full uniform representing their country or perhaps in a more casual setting. This ongoing conversation is very important for me. I am not interested in entering spaces and just drawing out the rules. One thing I can say is that I am very lucky that, with all my projects, I have met some incredible women and that even today we are very much in touch. I did a story during the pandemic on ASHA workers, who are social health workers. I had photographed one of them throughout their day. She was on the cover of TIME Magazine and we continued to keep in touch. When her daughter got married earlier this year, she invited me. And when she started a protest again earlier last year, I went there and I photographed her and her comrades. Whenever she is in Mumbai or when they are not being paid their wages, we have a conversation around that. It is really about these tender moments for me and just not allowing photography to be restrictive.

From the series Champion (Prarthana Singh. 2015-ongoing. Image courtesy of the artist.)

UD: What were some of the responses that you got from the children after they looked at Rembrandt's work and what associations did they make? What was the process of getting the children familiar with the cameras and developing the cameras?

Juliette Buss: Photoworks always collaborates with artists to lead our young people’s programme as a way of revealing and demystifying what artists do and also because they bring unique perspectives and viewpoints to the creative programmes. We selected artist Alejandra Carles-Tolra specifically because, although she is a photographer and not a painter, her work explores identity, particularly group identity and community identity through portraits. Her perspective was key in helping the young people develop and articulate their own responses to Rembrandt when they saw it at the National Gallery in London.

We assume that young people find it difficult to connect with historical artworks, particularly oil paintings such as those by Rembrandt. However, once you provide them with strategies, tools and ways in, and encourage them to ask questions, they can relate to the story that the painting is telling and the intentions of the artist. Then the young people can connect and understand what is relevant to them. Then they are much better equipped to respond creatively.

From the project Hey! Rembrandt (© project participants with Alejandra Carles Tolra. 2023-2024. Image Courtesy of Photoworks.)

Alejandra encouraged the young people to recognise that Rembrandt was himself performing as he staged his painting—considering his costume, pose and gaze—in order to tell a particular story about himself at that moment. The young people took that into their own photography, looking at historical and contemporary photographers and the ways in which they used staged and performative image-making to communicate their ideas. Of course, young people are immersed in selfie culture and social media, but actually, Alejandra asked them to unpack those kinds of images by considering more deeply how they convey meaning. You can see the influence of social media, but there is also a strong sense of their developed visual literacy that comes through their artworks.

From the project Hey! Rembrandt (© project participants with Alejandra Carles Tolra. 2023-2024. Image Courtesy of Photoworks.)

Since we feel the most important legacy of our programmes is to do with creative skills and visual literacy, and also because we understand that many young people won’t have access to DSLRs once they leave us, at Photoworks, we are always more interested in developing young people’s ideas and supporting their ability understand image-making, rather than getting hung up on the tech side of photography. The programme started with Alejandra and the team introducing the basics of how to use a camera, but then Alejandra focused on concepts and challenging young people to push their ideas and thinking further, and used her own expertise to help young people realise their ideas.

To learn more about the 2024–25 edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, read Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with the curators of the primary shows.

To learn about the previous editions of the Chennai Photo Biennale, revisit Najrin Islam’s conversation with Zishaan Latif on his series The Art of Hatred: The Aftermath of North-East Delhi Riots (2020), Annalisa Mansukhani’s conversation with Arthur Crestani on his series Aranya (2018), Mallika Visvanathan’s conversation with Parvati and Nayantara Nayar on their work “Chicken Run” as part of their project Limits of Change (2021), Ankan Kazi’s conversation with Ahmed Rasel on the series Nocturne (2021) and Sukanya Deb’s essay on Katja Stucke and Oliver Sieber’s video project The Indian Defence (2021). Also watch the episode of In Person featuring Varun Gupta, the founder of the CPB, in which he speaks about audience engagement and the biennale format.