Revisiting Historiography: Photographing the Two Bengals

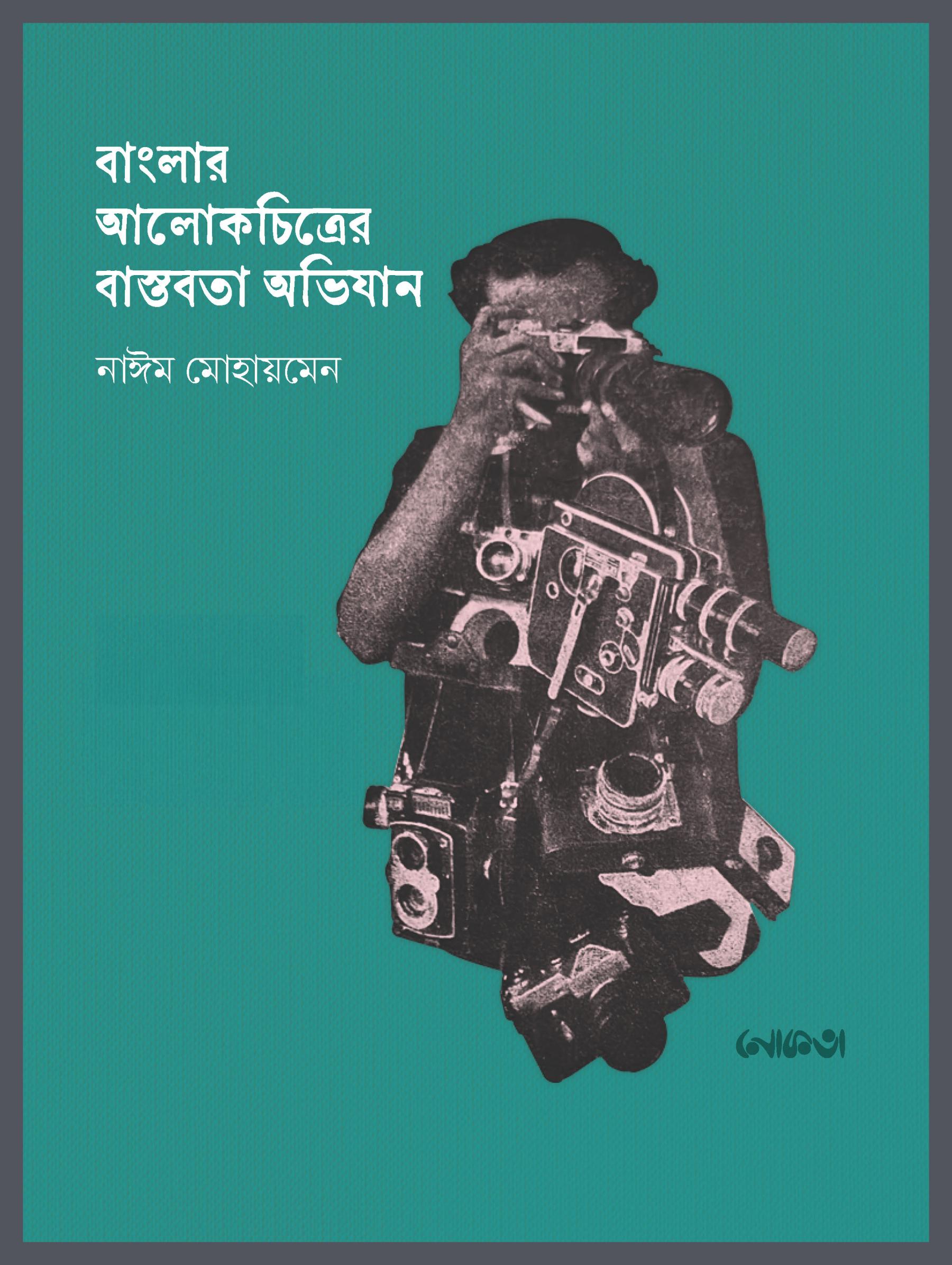

Cover of "Bengal Photography's Reality Quest" (2024): image by Manzoor Alam Beg, from back cover of his "Modern Photography" (1974). © Begart.

In the pre-launch to his upcoming book Bengal Photography's Reality Quest (2024), Bangladeshi filmmaker and academic Naeem Mohaiemen presented a historiography of Bengali photography, literature and film, specifically its politicised deployments between Bangladesh (as East Pakistan and after independence) and West Bengal within India. The terms ‘Bengali’, ‘Bangladesh’, ‘East Pakistan’, ‘East Bengal’ and so on become a technical articulation of specificities within East Bengal and Bangladesh’s timeline as a politico-linguistic identity and nation-state. In the presentation, Mohaiemen focused on the history of social realism and social documentary photography in the two Bengals to consider the claims that have been made through photographic practices and circuits. Social realism is a style of photography that accentuates depictions of social issues.

Naeem Mohaiemen at the pre-launch for Bengal Photography's Reality Quest (2024) at IIC, New Delhi. (January 3rd 2025. Image courtesy of The Alkazi Foundation for the Arts.)

In the introduction to the Alkazi Foundation event, curator and publisher Rahaab Allana asked Mohaiemen, ironically, if he would consider his practice to be one of “revisionist history”, since he considers state narratives critically while producing his own research-led historiography of the region. While Allana’s reference to revisionist history pertains to the wider environment of regime-led rewriting of histories especially in the context of the three countries, Mohaiemen referred to the book as emerging from the dichotomy of “unreliable memory” and political claims in history-writing, “straddling” the two Bengals, where he provides a critical perspective.

Mohaiemen began his presentation by speaking of two photographs taken thirty years apart; the first being Tarak Das’ documentation of Mahatma Gandhi’s visit to riot-torn Noakhali in 1946, and the second being an image of rehearsals for war by Bangladeshi photojournalist Rashid Talukder that documented Bangladesh’s Liberation War of 1971, where we see women marching with symbolic weapons. In the former photograph, we see Gandhi in the midst of a group of people, where the image indicates a cluster of disorientation and grief.

Tarak Das, Gandhi visiting riot-site at Noakhali, 1946. © Tapan Das.

Much of Talukder’s archive was hidden away and only given over to the photo agency Drik, founded by Bangladeshi photographer Shahidul Alam, for preservation and digitisation in 2016, a year before Talukder’s death. Mohaiemen refers to this particular photograph by Talukder as being an iconic image in Bangladesh, whereas the Noakhali photographs had faded from public memory. Besides the fragility of memory, we can see the distribution of photographs—between photojournalists printing their work in newspapers to reach a wide circulation versus the silencing of photographers—as producing a complexity in looking at these archives. Archival projects such as Mohaiemen’s become important in reproducing overlooked histories.

Rashid Talukder, Chatra Union (left student group) members, on the eve of liberation war, 1971. © Rashid Talukder / Drik.

Prior to social realism in East Bengal/ later Bangladesh, studio photography and pictorialism were prominent styles of the region. There was a strain of social realism that developed, where Mohaiemen spoke of the typical subjects of Bangladeshi photography that looked to fit within the mandate of these organisations, showing climate change, village life and urban survival. Upon further consideration, one can note that funding is linked to the creation and circulation of photographs. We can see a reflection of social realism in painting from the region as well, through artists such as Zainul Abedin, who captured the Bengal famine in 1943, pre-Partition.

A focal point of the talk was Bengali poet and musician, Kazi Nazrul Islam, who has been claimed by the three countries, having grown up in pre-partition India, and appearing on each of the nations’ stamps. His Muslim identity was politicised by Pakistan, prior to Bangladeshi Independence, and provided as an alternative example to Rabindranath Tagore. Due to a neurological disease he spent much of his latter years without speech, and Mohaiemen highlights how he became a “site of projection.” Mohaiemen also presented a photograph of the poet and his wife, Promila Debi, by Sayeeda Khanam from 1960, where we catch a glimpse of the distance between the two figures as indicative of a certain ennui felt by Islam, mirrored by Promila Devi, who we can see as separated and looking seemingly wordlessly at the camera.

Naeem Mohaiemen, Kazi in Nomansland (2008). Image courtesy of the artist.

Important figures that moved away from salon-style photography, which was geared towards exhibitions and competitions, towards social documentary included the likes of Manzoor Alam Beg, Golam Kasem Daddy, Anwar Hossain, Shahidul Alam and Sayeeda Khanam. Their photographs addressed social hierarchies by shifting the frame of the photograph. We see a photograph by Alam, where a domestic worker watches television from a different room than the family. Notably, Mohaiemen mentioned that this photograph was taken within Alam’s own family home and that this gesture of shifting the frame to foreground the domestic worker was aimed at rejecting societal stigmas. Khanam’s portrait of a female domestic worker created waves of tension as the naturalistic depiction, with the woman smiling in a sari, her shoulder uncovered, was considered too innovative for Bengali social norms.

What ran through the presentation was the challenges and barriers to pan-Bengali solidarity, which Mohaiemen spoke about to some degree; while there is reverence of photographers and writers associated with West Bengal in Bangladesh, the opposite is not necessarily the case. An attempt at crossing the border between West Bengal and Bangladesh was A River Called Titas (1973) by Bengali filmmaker Ritwik Ghatak. What does the future of Bengali solidarities look like?

Upon being asked about his methodology, Mohaiemen said,

“I have a very poor memory for daily, everyday things. [...] If my most immediate memories are so fragile or keep getting erased by whatever is getting put on top, then how fragile must distant memories be? [...] The period that I look at in my films—which is the Cold War of the 1960s and ’70s—is a period where documentation is, in many instances, lost. This idea of memory shaping events is very distinctly there, because if my recall of the event is the only record that exists, then my oral history becomes the document. It is relevant to put all of it into question; into discussions of ambiguity. Generally, in terms of historical debates that run through all nations, I am trying to argue for more ambiguity and less certainty about the way things happen.”

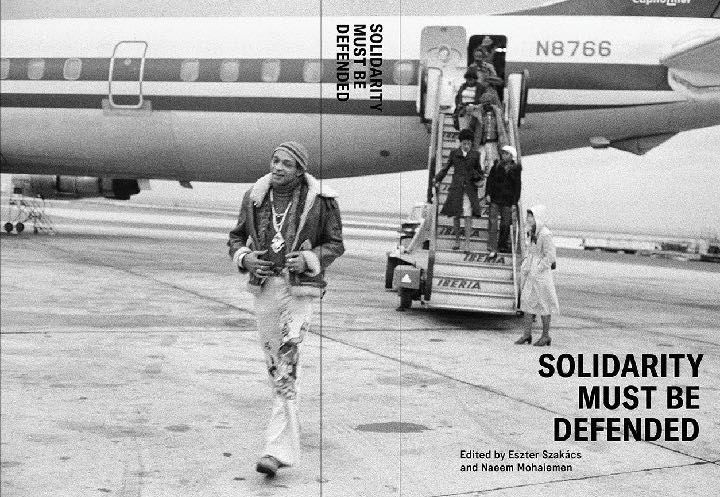

Book jacket image for ‘Solidarity Must Be Defended’ ed. Eszter Szakács and Naeem Mohaiemen; Cover image: © 2023 Marilyn Nance/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

To learn more about Naeem Mohaiemen’s practice, revisit his talk on his book Midnight’s Third Child (2020) as part of ASAP | art’s public programming and Najrin Islam’s review of the film Jole Dobe Na (2020).

To learn more about still and moving images documenting Bangladesh’s birth, read Ankan Kazi’s essays on Bangladesh’s short films as alternative cinema, Sayeeda Khanam’s practice, a review of John Hood’s The Bleeding Lotus (2015) and a curated album focusing on the representation of the Mukti Bahini.