Charandas Chor: Shyam Benegal’s Children’s Film

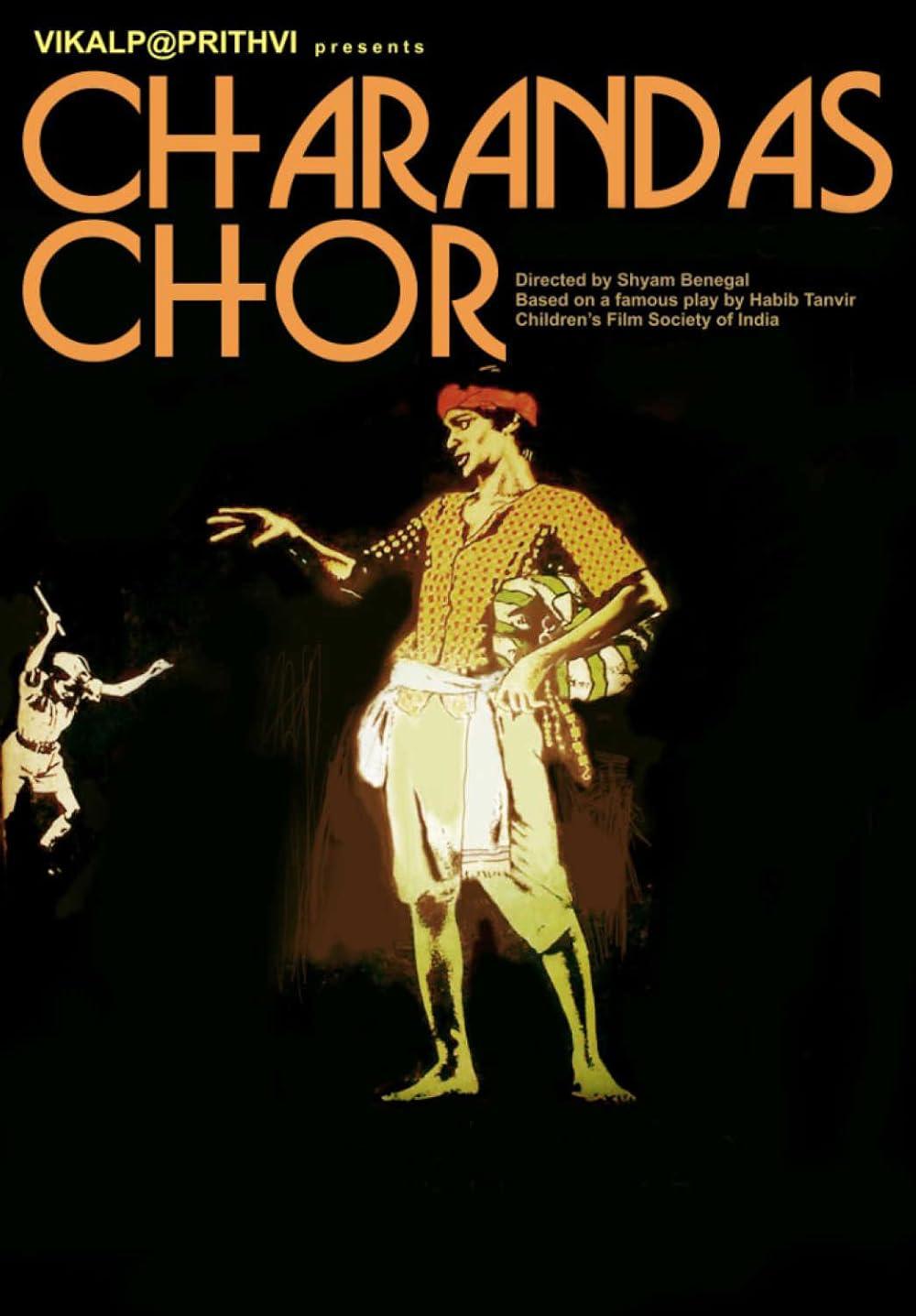

A poster of the film Charandas Chor (1975).

The film Charandas Chor (1975) was screened at the NFDC-National Film Archives of India (as a part of the Film Circle screenings) in memory of the late director Shyam Benegal. Benegal’s name is often associated with the keywords Parallel Cinema, Realistic Films, Film Society Movement and so on. Showcasing a film produced by the Children’s Film Society of India aptly highlights the ample range of his filmography.

Charandas Chor is an adaptation of Habib Tanvir’s seminal play of the same name, which itself is an adaptation of a Rajasthani folk tale by Vijaydan Detha. Much like Tanvir’s other works, Charandas Chor finds its roots in folk tales, folk culture and, most importantly, comical storytelling. Charandas is a small-time thief, a chor, who steals, wears a disguise and keeps the police baffled, all the while keeping a big grin on his face. Charandas’ life starts to take a turn when he steals from Buddhu Dhobi, who instantly wants to become his apprentice by learning how to steal. Taking note of Buddhu’s efforts, Charandas takes him under his wing and the duo make a name for themselves, Charandas much more so. Their lives take another baffling turn when they land in trouble after one of their adventurous thefts and are about to be arrested.

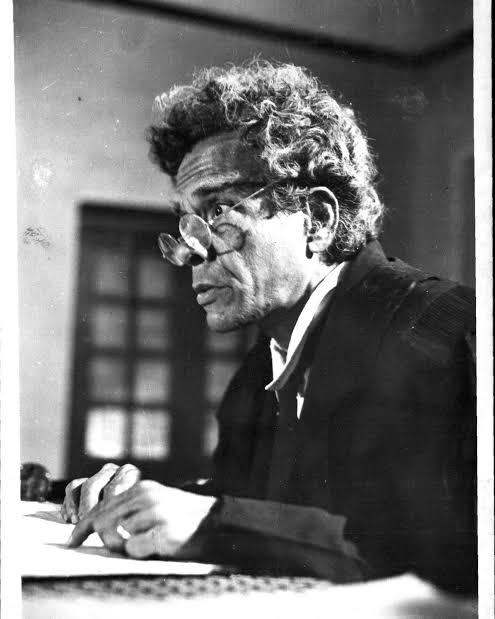

Playwright Habib Tanvir as a magistrate.

At this point in the plot, Charandas comes across a spiritual guru, who asks him to swear to him that he will never eat if someone serves food to him on a gold plate, never lead a procession that is in his honour, never become a king and never marry a princess. Poor, old yet cunning Charandas agrees to this out of desperation, believing all of these outcomes are impossible to achieve. His Guru, however, adds a fifth vow—never to tell a lie. Thus, Charandas Chor becomes a man of principle, an honest thief. This fifth vow of his becomes the provocation of the story. A man of integrity in a world of vices. Paradoxes such as this are at the centre of the film.

Director Benegal and cinematographer Govind Nihalani borrow the visual comedy of physical gags as well as the dynamic relationship between the camera and the actors from the likes of Charlie Chaplin and Buster Keaton. The three bumbling, incompetent police officers in the film resemble the ‘Keystone Kops’ from the era of silent slapstick comedies, while a nearly ever-present donkey in much of the runtime of the film, a four-wheeler being pushed by Buddhu (because Charandas does not know how to drive, and yet the duo wants to steal it!), and a lot of chase sequences have their roots in the films of Chaplin and Keaton. All these visual gags, along with the music and songs with a tinge of different dialects, add to the comical nature of the film.

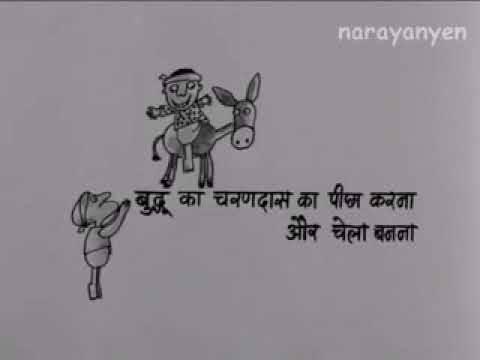

Buddhu and his donkey - A frame from the opening scene of the film.

Charandas Chor is not just a visual comedy or merely a children’s film. There is also a greater argument being made about how the world makes it impossible to remain truthful to your principles. Through the course of the film, Charandas becomes a renowned thief, is offered political power and Princess Kelavati (Smita Patil) asks him to marry her. Charandas has to say no to all of these things, which leads to his death sentence. This brings forth the eccentric nature of our reality, where a man is punished for his virtues. The moral dilemmas that Charandas faces arise due to the complex, paradoxical nature of his character—the world has no place for an honest thief. This highlights the hypocrisy of society as well as the blurred lines between right and wrong, which change according to societal norms and those who hold the power.

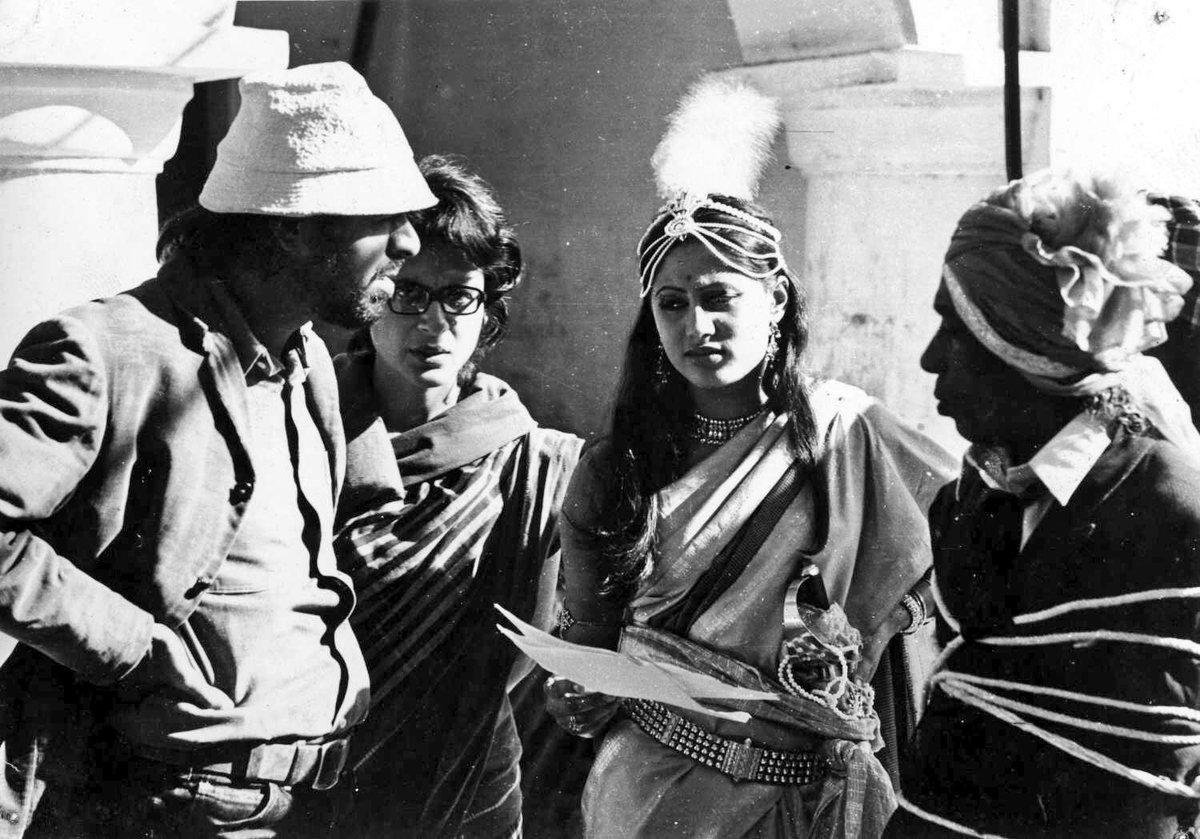

Smita Patil and Shyam Benagal on the sets of Charandas Chor. (Image courtesy of National Film Archive of India).

One such moral ambiguity is found in the character of Charandas’ Guru. The Guru preaches enlightenment and letting go of all worldly possessions. However, he is quite materialistic and never shies away from an opportunity to gain some money—either from Charandas or the princess. As Charandas aptly points out in one of the early scenes in the film, the Guru’s gig is much more steady and efficient, where he can earn while sitting idle under a tree; Charandas, on the other hand, has to steal to survive.

Charandas and his Guru.

Despite the serious themes, Charandas Chor is an entertaining comedy which presents a rare connection between film and folk theatre (as most of the artists in the film were associated with Tanvir’s theatre group, ‘Naya Theatre’). Benegal uses illustrated intertitle cards to give an episodic structure to the film, where each card has an illustration featuring Charandas, Buddhu and Buddhu’s donkey, all in different costumes and with different props. The film also breaks the fourth wall using an intertitle at one point where the images on the screen rupture and the question “कहीं फिल्म पूरी तो नहीं हो गई? (Is the movie over already?)” is asked by the narrator. These cards are read out by Tanvir, and he even fumbles while reading some of the words—just like a child would if they were reading it for the first time. These little touches make the film all the more beautiful.

An intertitle from the film.

This makes Charandas Chor an interesting entry in Benegal’s filmography as it is quite different from his popular body of work. Even though the points put forth by the writer and director have a certain depth and roots in reality, the film itself stays away from realism, and instead, it uses slapstick comedy and visual comedy to drive its point home. Benegal returned to the comedy space with his films Welcome to Sajjanpur (2008) and Well Done Abba (2010), but that film is a remake of a Marathi-language film (Jau Tithe Khau, 2007). Additionally, Benegal did not really make another ‘Children’s Film’ per se. The amalgamation of the visual setting and folk culture and music, the strong connection with the Tanvir school of theatre, and Benegal’s realisation of the acclaimed play make it all the more a unique work of art in Benegal’s filmography.

To read more about Shyam Benegal, read Sucheta Chakraborty’s essay on watching the restored version of Manthan (1976) in theatres.

All images are stills from Charandas Chor (1975) unless mentioned otherwise. Images courtesy of the director.