Mental Health and Neurodivergence at Chennai Photo Biennale

How do photographs speak to and about our inner worlds? How do they allow for conversations that are difficult yet important? At the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, photographs become biographies, helping us reflect on mental health and neurodivergence and its connection to the process of image making. Brindha Anantharaman uses photography to reflect on her own life, emotions and mental well-being. Gaza Seen by Its Children, curated by Asmaa Seba, presents photographs by six children from the Gaza Strip as part of an Art-Photo Project. Sathish Kumar, through his work titled Bubble, explores his own brokenness and void. Shankar Narayanan uses mixed media in his work to reflect on and articulate his own internal states of being that allow him to work with chaos and tension.

Jottings of an Unloved. (Brindha Anantharaman. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Anoushka Mathews (AM): How do the lens and camera become an entry point into talking about mental health? Why does photography as a medium become your language to make sense of things for yourself? What hope do you think your images could offer to those in similar states of being as you?

Brindha Anantharaman: Photography is often mainly associated with being an observational tool to capture the outside world. Mine is a first-person account and, hence, takes it to the core of my emotions, rather than being a third person’s POV (point of view). In these photos, you can find me feeling these moments rather than just seeing them as a photographer. The audience could feel these moments through me. If you are able to feel a photo, you are never likely to forget it.

Jottings of an Unloved. (Brindha Anantharaman. Image courtesy of the artist.)

During this journey, I realised how powerful repressed memories of childhood trauma can be. They still had the power to mould my being after so many years.

The most agonising feeling I had was a sense of being trapped in my mind with past memories. It seemed as though there was no way out. And I could not explain this feeling through words at that time; what I could not put into words, I was able to capture precisely with my camera.

Jottings of an Unloved. (Brindha Anantharaman. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Seeing my emotions as pictures gave me a kind of peace. Later, I realised it was my way of catharsis, and they formed a personal means to communicate with myself. Mainly, I continued to capture the stages of solace and acceptance, which I think is the essence of this story. It is not a story about trauma; it is about how I found kindness in the face of hatred. A testament to my resilience.

I have been witnessing people take hope and inspiration from my work. They wondered how I was able to capture exactly what they were going through, such as anxiety, depression or claustrophobia, etc., and, by extension, expressed how seeing these images assured them that they are not alone in this journey. My art has served its purpose. This was the reason I made this work. It is not just about me; it is for all of us. There is light at the end of the tunnel indeed.

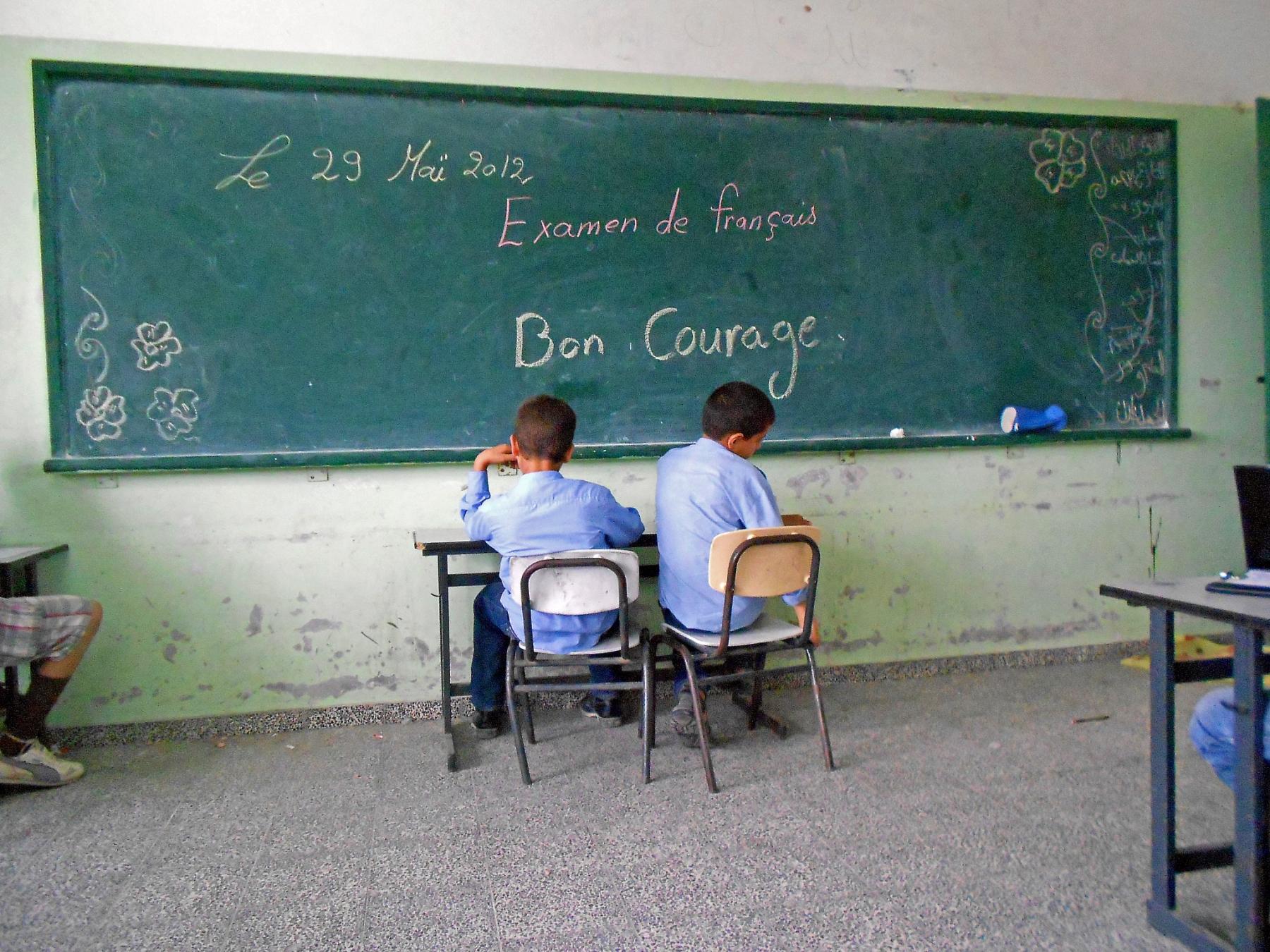

“Some of my friends at school don’t take studies seriously but I do, I want to have my diploma and have a good job to help my family.” (Photograph by Abdelfatah Saleh. 2012. Image courtesy of Asmaa Seba.)

AM: Why do you think art is important in the face of conflict and oppression? How can these images become the starting point to talk about the impact occupations and unending violence have on the mental well-being of those that reside in Gaza and Palestine, especially children?

Asmaa Seba: Living amidst the trauma of the 2008 Israeli operation Cast Lead, these young photographers faced unimaginable challenges, precarious conditions, loss and violence. Being behind the camera helped to distance themselves from what they witnessed and experienced every day in the refugee camps, the bombings and the harsh conditions. Most of the children who participated in the project had seen their parents or family members killed before their own eyes. Photography as therapy helped them share feelings they could not express with words.

“I like to learn French, it’s a beautiful language.” (Photograph by Rami Abu Jalila. 2012. Image courtesy of Asmaa Seba.)

War and occupation steal the innocence of the children—this is what I wanted to demonstrate with this project. I also wanted to share my passion for photography, which is an art of expression anyone in the world can use.

Each photograph tells a story—it is a testimony to the daily life of these children. They live in the biggest open-air prison the world knows. Using the photographs as a travelling exhibition has enabled them to contribute to the opening of a broad debate on the extreme suffering the children endure and on the dark future they face, those who have only known war as their daily life since their birth.

“I miss my parents, I go every Friday on (sic) their graves with my old brother and I tell them what I did during the week.” (Photograph by Walla Abu Musa. 2012. Image courtesy of Asmaa Seba.)

Continuing to create works of art in the midst of war and oppression is not only an act of creation, it is in itself an act of resistance and survival. While Israel makes every effort to erase life and culture in Gaza, continuity in art proves that life goes on and that Palestinian identity will not be erased.

From the series குமிழி/ Bubble. (Sathish Kumar. Image courtesy of the artist.)

AM: How do you find your work a reflection on your state of being? Amidst the many conversations about mental health, how do your images convey the unspoken and undefinable?

Sathish Kumar: As an introvert, photography is my way of connecting with the world and expressing my feelings. Each day feels new, offering lessons to learn and unlearn, helping me stay grounded and content. Even during difficult times, especially when I am without photo assignments, staying calm gives me clarity and helps me make better decisions.

From குமிழி/ Bubble. (Sathish Kumar. Image courtesy of the artist.)

For example, some of the images I captured in the forests for Bubble bring me a sense of calm and relaxation. They remind me that life moves on and everything unfolds in its own way. Photography helps me reflect on how time heals, guiding me through different moments in life with clarity and acceptance.

I am fully dependent on photography—it has been my connection to visual art since my teenage years. Every day, I stay committed to my practice, but when I shoot, I do not overthink it. I go with the flow of daily life, photographing what I love. In those moments, I lose myself in the process and forget my problems.

From the series குமிழி/ Bubble. (Sathish Kumar. Image courtesy of the artist.)

The world is always changing—naturally, biologically, chemically and psychologically—and I aim to capture the changes, both within and around me, by focusing on the beauty of everyday simplicity and the ordinary.

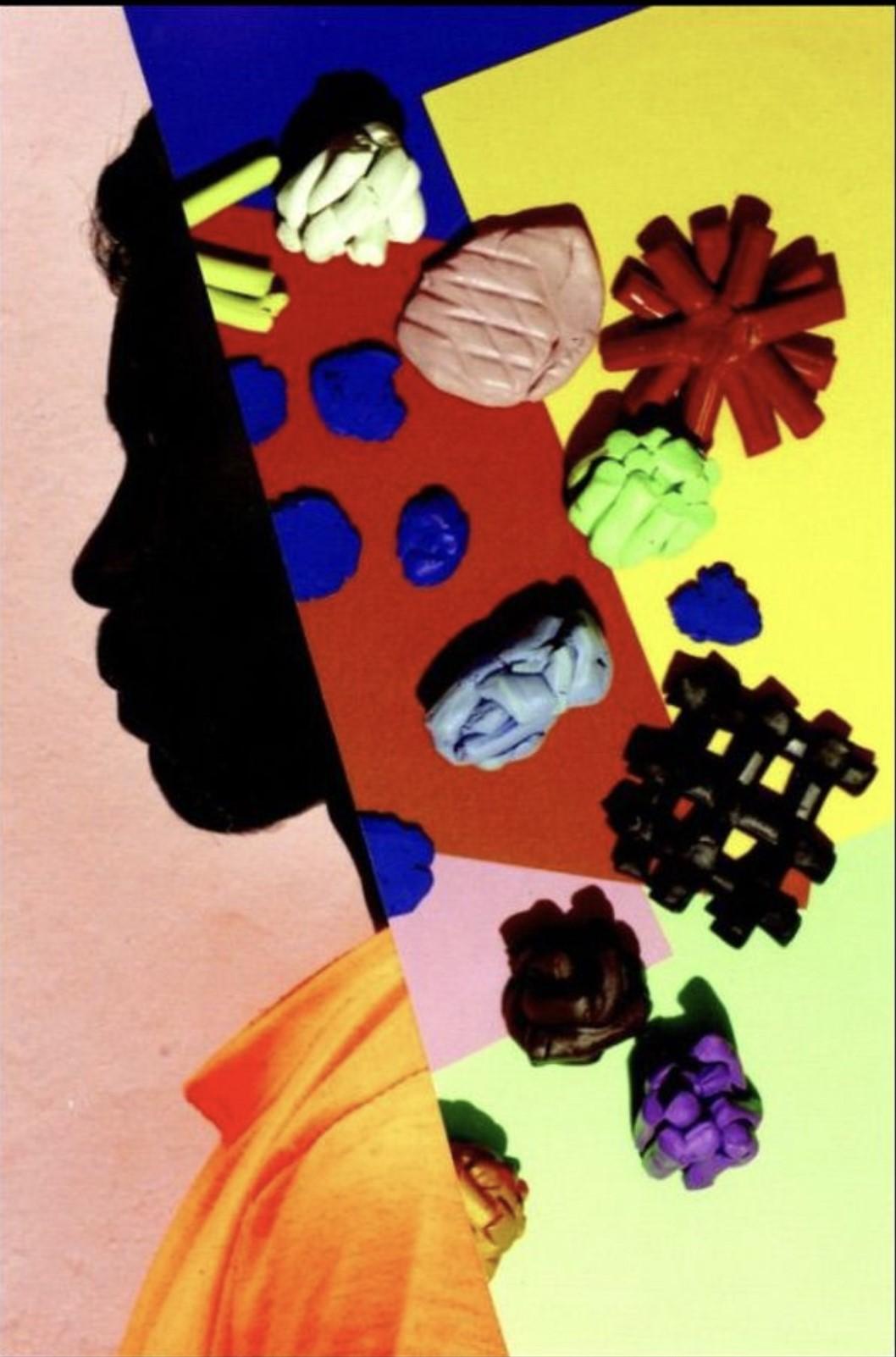

From the series Chemical Imbalance. (Shankar Narayanan. Image courtesy of the artist.)

AM: “I struggle with inner conflicts between what is real and what is not. All these are stopped after I take pills.” How does your work speak about this idea of what is real and what is not? What is your process of bringing these images together?

Shankar Narayanan: When I am off my pills, the world is intense—every sense sharpened, colour, form and sound vibrating in unfamiliar ways. Things are not as I knew them; they shift, become something overwhelming. After I take my pills, that world disappears. I recreate these experiences in my work, but from a steadier place.

Every moment holds many possibilities—tension, violence, beauty. Nothing changes except your viewpoint. Reality is unstable, but we try to shape it, hold it still—an illusion of order to protect us from its chaos.

From the series Chemical Imbalance. (Shankar Narayanan. Image courtesy of the artist.)

I do not know if I fully connect. There is always a gap. My process is not planned. I do not start with a clear idea. I take a photograph, then I begin to see—shadows, shapes, textures, colours, etc. I follow them, repeat them, distort them and build over them.

From the series Chemical Imbalance. (Shankar Narayanan. Image courtesy of the artist.)

To learn more about the fourth edition of the Chennai Photo Biennale, read Upasana Das’ short interviews with artists and practitioners exploring forms of community building and with artists whose practices explore themes of power and representation, Anoushka Antonnette Mathews' short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of bodies and landscapes, Kshiraja’s short interviews with artists whose practices explore themes of landscape and history and with artists whose practices explore themes of myth, ritual and identity, as well as Mallika Visvanathan’s short interviews with the curators of the primary shows.