A Shared Place Between Memory and History: Nimi Ravindran’s Exhibition-Performance

Nimi Ravindran speaks to the audience simply, without props, costumes or a stage, forgetting lines occasionally, sometimes by design. Charulatha Dasappa, her production manager, is seated close by, script in hand, prompting her forward. “I saw the mirror and remembered many things,” Ravindran says, going on to recall details of her childhood in Bengaluru, how her family came to acquire their first full-length mirror, her mother’s many talents, her public-sector job and, later, her illness and memory loss. To Forget is to Remember is to Forget, Ravindran’s exhibition-performance which had its tenth iteration last month at the Goethe-Institut in Bengaluru (also known as Bangalore), uses video, sound, photo and print installations as well as a storytelling performance to explore personal and public memory. Jumping back and forth between decades, through narrative routes that are direct, roundabout, abstract and material, Ravindran’s work returns each time to a feeling of accelerated forgetting at the simultaneous levels of the familial, the neighbourhood, the city and the nation.

Installation view of "Akashavaani" at Bangalore International Centre. (Nimi Ravindran. Collaborators: Baan G and Sachin Gurjale. Songs contributed by Charulatha Dasappa, Nimi Ravindran, Pallavi M D, Bindhumalini Narayanaswamy and Mansi Multani. 2024. Sound Installation with tape recorders, transistors, radios, MP3 player and speakers. Image credit: Aakriti Chandervanshi.)

The family’s full-length mirror, for example, is carefully contextualised during Ravindran’s performance. It is by winning a singing competition on ‘Hindi Diwas’ at her public-sector job in Bangalore in 1993 or ’94, that Ravindran’s mother purchases an almirah, a Godrej knockoff, with a mirror on its door. Ravindran spends as much time over Bangalore’s story as she does on her mother—the two are rarely separated. As Ravindran’s mother forgets certain fixtures of her daily life, Bangalore, in parallel, becomes a city that builds over its distinguished structures and lakes so rapidly that very few can recall each change. In this way, the feeling of loss—when it arrives and returns in a looping timeline—has a doubleness. It bears the weight of both Ravindran’s mother’s passing and a city with its own failing memory, where histories are lost or re-written, sometimes in deliberate, politically-motivated acts of remembering and forgetting. The mirror-object, perhaps as a stand-in for this doubleness, appears as a kind of refrain across the performance and exhibit. Ravindran’s show demonstrates how solely autobiographical memory cannot stand sturdy unless it is bolstered by personal and collective memories of the city or even the country—the larger histories within which that personal memory is enmeshed.

Installation view of "Photo Booth" at Bangalore International Centre. (Nimi Ravindran. Collaborators: Rency Philip, Aakriti Chandervanshi, Baan G and Sachin Gurjale. 2024. Sound and photo Installation with archival photographs, acrylic box, mirror, MP3 player and speakers. Image credit: Aakriti Chandervanshi.)

Each exhibit in To Forget is to Remember is to Forget offers a different context in which to consider the idea of memory, using lines or details from Ravindran’s performance as starting points. In the installation titled “Photo Booth,” visitors are invited to peek into a box covered on the inside with old passport photographs of Ravindran and her mother, as well as similarly sized mirrors. As visitors encounter the different colour tones of passport photos through the decades—different versions of Ravindran and her mother—and slivers of their own reflections, a recorded voice narrates stories. Ravindran emphasises that these are not for “just nostalgia and pleasant things,” but also stories that mark remembrance of moments of civil and political unrest in the city and country, such as the riots of 1984 in Delhi and 2002 in Godhra.

Still from Placebo. (Nimi Ravindran. Collaborators: Ben Brix, Baan G and Sachin Gurjale. Ben Brix’s participation supported by the Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan 2023. 2 Channel Video, 12 min loop. Image courtesy of the artist.)

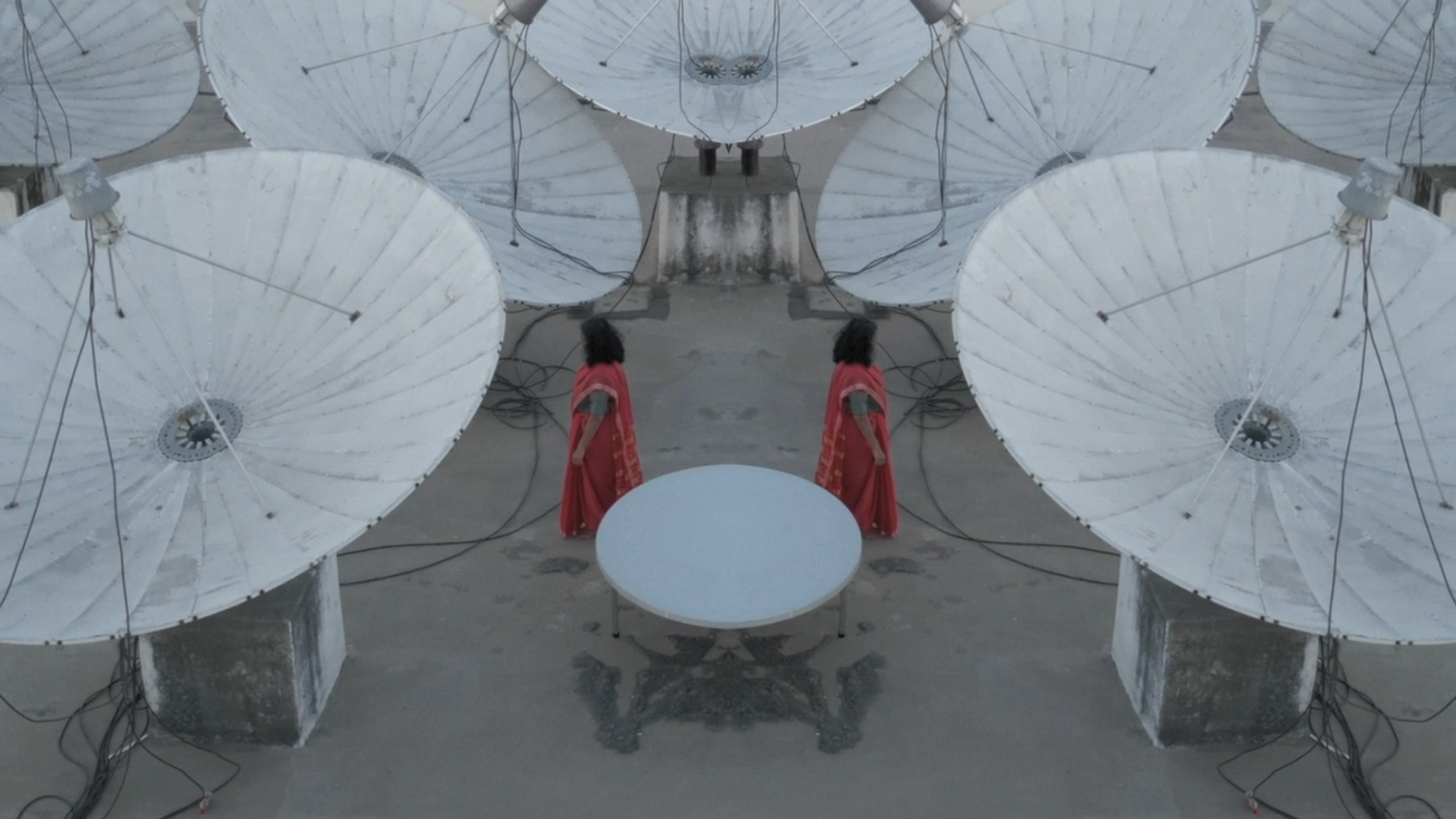

In the video installations Mirror, mirror and Placebo, viewers find themselves in abstract versions of Bangalore, played in a loop, in the real-time pace of daily activities. Placebo is set in an empty garage, with Ravindran sitting at a table with multiples of herself. Each makes a fold in a cloth before passing it on. In Mirror, mirror, a terrace is split down the middle, each half perfectly reflecting the other. Two women, both Nimi Ravindran, trudge along in red cotton sarees. They move forward, or wander, or simply try to not get swallowed up, to not collide completely with the other—that shadow walking alongside. When the reflections do meet, they overlap into a soft fluttering bird and shrink into a small Rorschachian moth—parting, then pushed together, towards the same mysterious fulcrum.

Still from Mirror, mirror. (Nimi Ravindran. Collaborators: Ben Brix, Samrat Chandanshive, Baan G and Sachin Gurjale. Video, 6:36 min loop. Image courtesy of the artist.)

Ravindran’s multiples appear to each have an invisible task before them. As they fold clothes, or walk, or wait, or sit beside each other, the women seem also to be memory-keepers. They recall the collection of their mother’s memories and the grief of her passing; they consider their own present and their own forgetting of details as time passes—all in a manner that feels matter-of-fact and routine. Their movements resemble the practice of remembering-through-repetition that one might encounter at school. The video installations, like Ravindran’s performance, are a kind of memory-in-action, where visitors are invited to witness loss, forgetting and a new narrative or routine being forged out of these, akin to Elena Ferrante’s narrator in The Story of the Lost Child who confesses, “Night after night, I went around recognising myself in an idea that suggested general disintegration, and at the same time, new composition.”

Installation view of "Library of the Lost" at the Bangalore International Centre. (Bengaluru, 2024. Image credit: Aakriti Chandervanshi.)

One corner of the exhibition is a display of around 200 jars arranged across tables and shelves. Each contains a folded piece of paper tucked into them. Ravindran explains, “While writing, I was also collecting every little thing my mother forgot which I could remember. Even small things: somebody’s name, what a cousin is doing, how tall my brother is.” In the installation “Library of the Lost,” each of these details is carefully stored in glass. Visitors are invited to participate in retrieving and deciphering Ravindran’s mother’s memories by opening the jars to find fragments such as “G121, HAL colony, my house,” “masala chai: considered liquid biriyani” and “height 5’7.” There are song lyrics, proverbs and her husband’s name.

Installation view of "Library of the Lost" at the Bangalore International Centre. (Bengaluru, 2024. Image credit: Aakriti Chandervanshi.)

Like Ravindran’s storytelling, “Library of the Lost” underscores the show’s authenticity while bypassing the hyper-confessional tone sometimes associated with personal narratives. In part, this is created by the exhibition’s open-ended design, where visitors discover parts of Ravindran’s stories with some control, choosing how many jars they want to open or how much of a video-loop to watch. This helps visitors modulate the focus between personal details from Ravindran’s story and the more metaphorical and formal aspects of the displays on their own terms. Ravindran’s methods of contextualising her and her mother’s stories using shared popular media and historical events create a sense of enquiry that is as much about the public in which the artist finds the familial embedded. The glass jars not only provide storage and protection for her personal memories, they also allow for distance from the material.

Nimi Ravindran performing To Forget is to Remember is to Forget. (Bengaluru, 2024. Image credit: Aakriti Chandervanshi.)

During her performance, Ravindran describes how, before the arrival of the almirah, her family had owned a one-by-one-foot mirror, kept in the bathroom, tightly framing each person’s face. “We didn’t really need a mirror,” she says, “We relied on each other and asked each other. My mother would ask me and my brother if her bindi was off-centre.” Ravindran’s show makes memory about more than one’s personal feelings and recollections—it becomes a matter of relying on each other. Ravindran mentions that after some of her performances, audience members have come up to her to share various coincidences and connections they have with her story, her mother’s life and work, and the films and songs she loved. “What we imagine as ‘lost’ is not lost. It just exists somewhere else,” Ravindran says, “in someone else’s memory.”

Still from Placebo. (Nimi Ravindran. Collaborators: Ben Brix, Baan G and Sachin Gurjale. Ben Brix’s participation supported by the Goethe-Institut / Max Mueller Bhavan 2023. 2 Channel Video, 12 min loop. Image courtesy of the artist.)

To learn more about artists navigating memory through their work, read Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Soumya Sankar Bose’s images of the massacre of Dalit refugees by the Left Front in West Bengal’s Marichjhapi in 1979 and on Mitul Kajaria’s catalogue of the self, as well as Abilaschan Balamuraley’s conversation with Liz Fernando’s construction of imagined memory in retelling stories of forced migration in Sri Lanka.

To learn more about artists working with doubles and multiples in their work, read Anisha Baid’s essay on Kiran Subbaiah’s video works and Najrin Islam’s review of Geetika Narang Abbasi’s Urf (2022).