Urf | A.K.A.: On Economies of Adoration in Bollywood

While stardom is a common cultural phenomenon, a distinct manifestation can be seen in the case of Bollywood. In the 1970s, the male star’s portrayal of heroism on screen was marked by Amitabh Bachchan’s “angry young man” persona. The actor rose to popularity through this diegetic assumption of subaltern rebellion. Before Bachchan’s iteration of the “hero,” Dev Anand represented the quintessence of romance on screen and generated an enduring fandom. In the 1990s, Aamir Khan and Shah Rukh Khan (SRK) became the cosmopolitan and consumerist romantic heroes of Bollywood, while Salman Khan marked a return to hetero-normative masculinity through action-thrillers. Through their auratic presence, stars give rise to extra-diegetic bodies—the “hamshakals”, “dummies,” and “carbon copies”—that partake in a parallel economy of production, circulation and exhibition. Screening at the Dharamshala International Film Festival 2022, Geetika Narang Abbasi’s documentary, Urf | A.K.A. (2022), delves into this economy of admiration. She focuses her lens on the purported lookalikes of the aforementioned stars and their individual trajectories through the vagaries of an informal, and often harsh, industry.

Referred to by the prefix “Junior,” the lookalikes’ profession is premised on imitating the “Senior” referents, thus adopting the position of a protégé rather than a “duplicate.” Occupying the margins of Bombay cinema, Kishore Bhanushali became popular after his imitation of Dev Anand in the film Dil (1990), and has since acted in several fringe movies. He insists that he imbues his imitation of Anand with his own personality, such that the resulting performance is distinct to his person. As a result, he believes that any neophyte intent on forging a career out of this would have to copy him (Bhanushali), and not Anand. This statement establishes showmanship as a rite of sorts, with screen personalities almost fated for a transfer of mannerisms through time. Capitalising on his popularity as an impersonator, Bhanushali has also carved out a career in light music today by singing at weddings and corporate events.

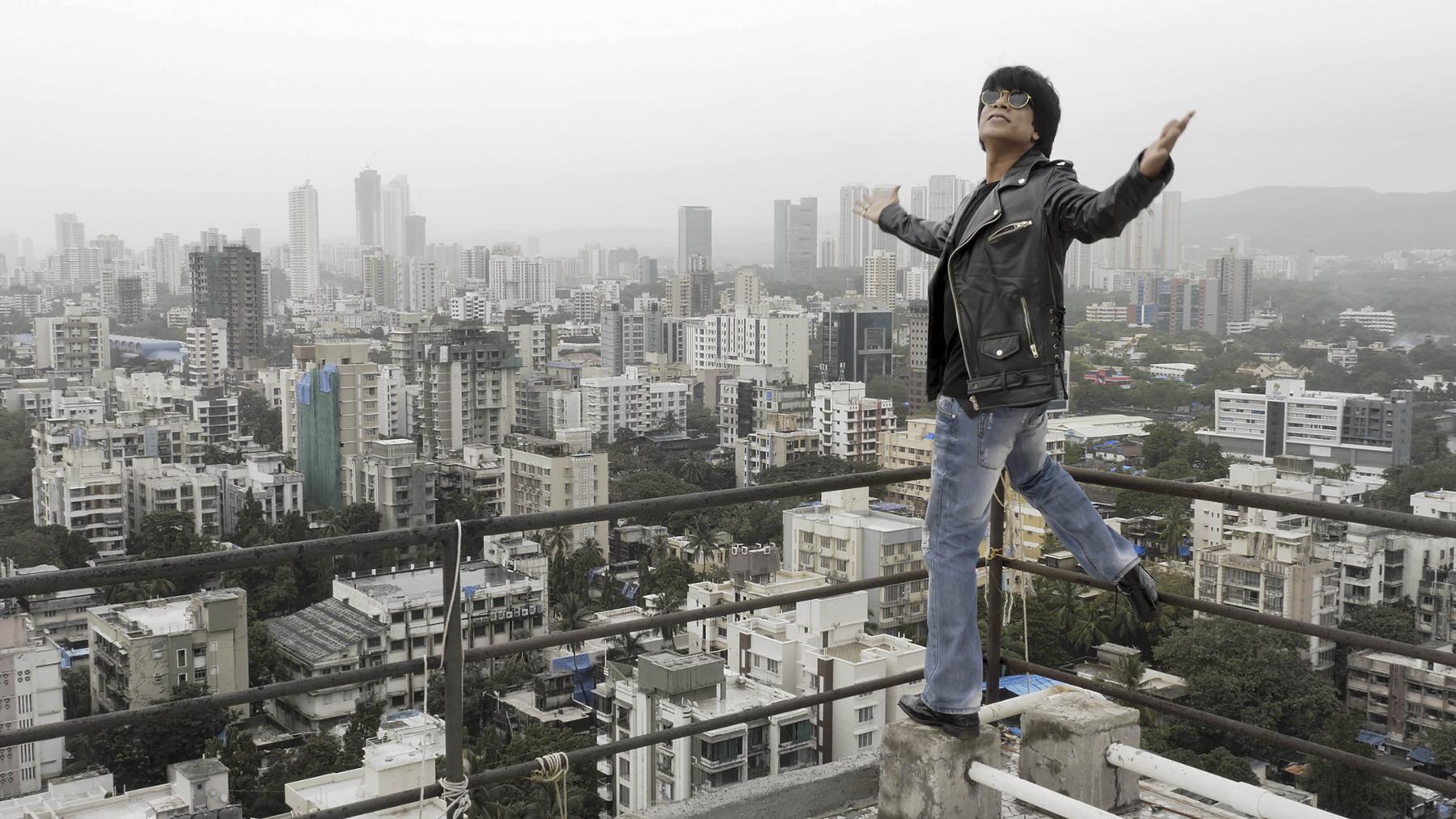

Prashant Walde plays Junior Shah Rukh Khan, primarily in the capacity of a body double for commercials and film scenes involving wide and back shots. At one point, he talks about paying acute attention to the physical characteristics he shares with SRK—including his kanth (Adam’s apple)—which, he believes, bolsters his legitimacy as a double. Taking a leaf from SRK’s evident reciprocation to overtures of love from ardent fans, Walde obliges requests for selfies when he meets his own admirers. The paradox is that the latter set of admirers constitutes a borrowed stardom for Walde, as it arises from their knowledge of SRK’s elusive power. But in persisting with and against the phenomenon, Walde has carved out a successful profession in an industry that both seeks and derides his body for vicarious thrill. He often delivers SRK’s recognisable film dialogues in vernacular Bhojpuri, effectively tailoring his star persona for local consumption.

Junior Amitabh Bachchan is an outlier in that he does not physically resemble the star he imitates—a fact that does not escape the attention of his employers. Firoz Khan has therefore had to work intensively on the attributes distinct to Bachchan—such as his baritone, vocal inflections, wavering gaze, and nonchalant demeanour—all of which now constitute the desired resemblance to the star. Khan insists that his “hard work” and research as well as additive and cosmetic accoutrements (such as Bachchan’s comely white beard) are responsible for his professional success. He participates in parodies and primetime shows to generate ample revenue. Having established his reputation through this channel, Khan now plays different characters on television shows in an effort to move beyond a personality founded on imitation.

In the film, Abbasi interviews the actors away from their professional settings (and thereby the performative adherence to mimicry they might have inspired). Her methodology for the documentary involves conversations in the spaces of their homes instead. This establishes the conditions for sincere dicussions about the intricacies of their craft, associated anecdotes, and involvement of family members in their preparatory processes. Their partners are included in these exchanges, which offers a fresh perspective on how the actors are looked at differently in the domestic sphere. These actors are not merely “shadows” or fans of the stars they imitate, but performers in their own right who once dreamed of breaking into the Hindi film industry. As low-cost substitutes for stars, the actors work with perpetual self-awareness about their secondary status in the industry. They are also routinely typecast, which leads to the regurgitation of tropes to the point of exhaustion. All three of Abbasi’s protagonists share the common desire to nurture the dormant actors within themselves. While some are successful with the turnover, others are not.

The industry of impersonation has mutated today, with no star figure from the younger generation commanding the same kind of screen-power as compared to the ones discussed. With a significant shift from “andaaz” to naturalistic acting, the “hero” has disappeared, rendering the performative syntax difficult to imitate. Stars are also hyper-visible on a range of promotional platforms, which effectively shrinks the enigma and distance that were previously associated with calculated appearances in public spaces. Celebrity is not as sparse as it used to be either, with a proliferation of lookalikes on social media platforms with their respective fan following. The documentary then captures a moment in time when lookalikes still constituted an industry, which revealed a homoerotic obsession of male impersonators with their star idols. This is evident in the former’s love for the latter’s image—in how the impersonator would repeatedly view and fixate on the minutest mannerisms of the star in an effort to assimilate them. Is the resultant uncanniness fully contrived, or cultivated through a predisposed similarity? The lines remain quite blurred.

To read more about stardom and its visual cultures in South Asia, please click here, here and here.

All images from the film Urf | A.K.A. (2022) by Geetika Narang Abbasi. Images courtesy of the director and the Dharamshala International Film Festival (DIFF).