On a Schizophrenic Viewing Practice: In Conversation with EXCISE DEPT

EXCISE DEPT (L-R) Karanjit Singh, Rounak Maiti, Siddhant Vetekar and Andrew Sabu.

The first time I encountered EXCISE DEPT's work was when a friend posted “LIFE'S A GAME” which the audio-visual collective had just released. It was a cornucopia of surrealistic humour embedded in the magic realism of everyday acts like opening a microwave to find a toy chicken and eggs. They were filming in a Punjabi magician, Jatinder Singh Babbar’s house, whose space was made into this surrealist habitat—not unlike how the magician himself lived, I would find out from them later.

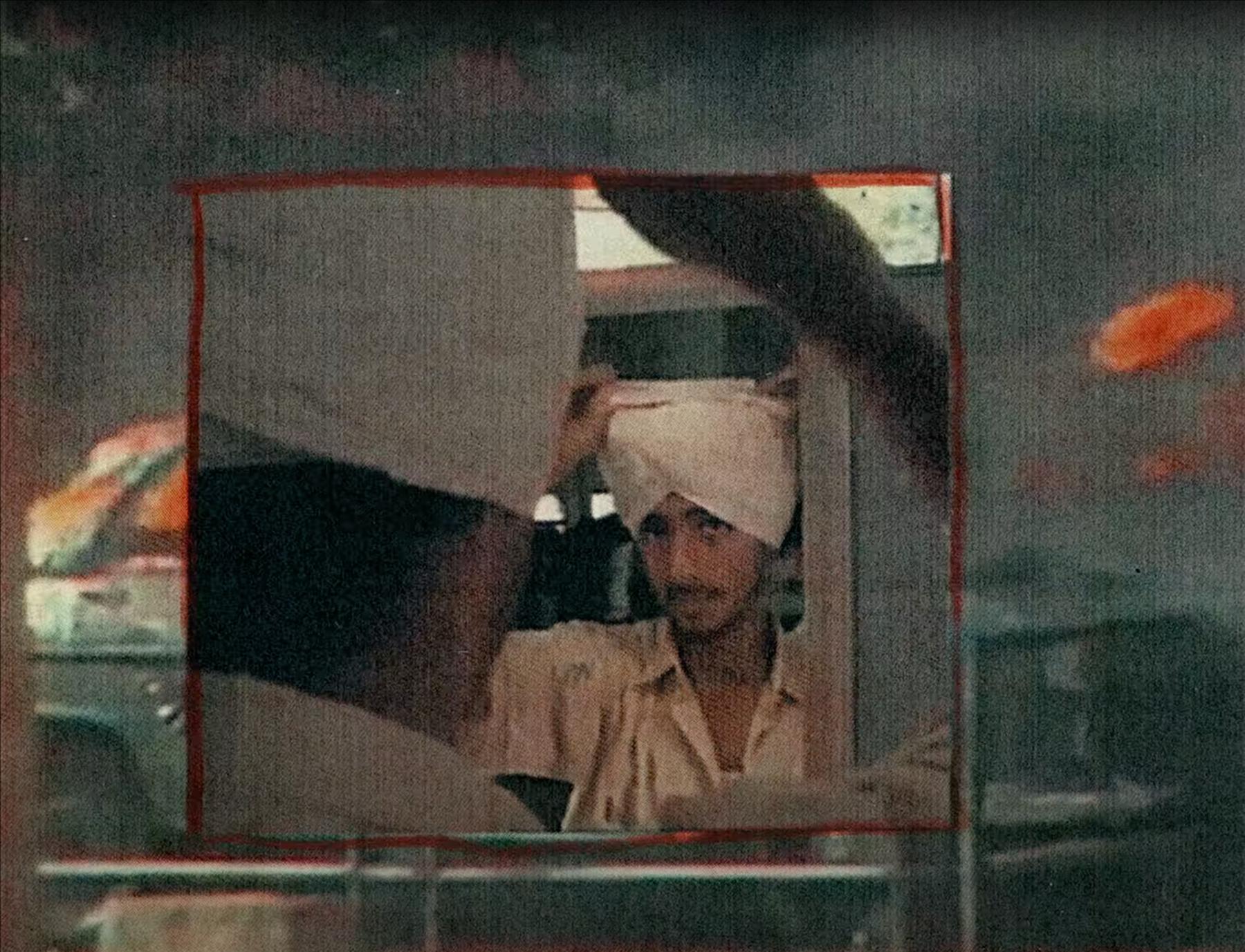

Still from 'POLICE STATE'.

Their entire universe has been crafted into a portmanteau, where multiple aspects of Sikh identity, existing under orange nationalism, the idiosyncrasy of political Whatsapp forwards and distraction in a digital life all merge together. This is EXCISE DEPT, in their most comprehensive interview till date, of which this is the first of three parts. Rounak Maiti, Karanjit Singh, Siddhant Vetekar and Andrew Sabu speak about their self-fashioning as government karamcharis (workers/employees) gone rogue and the significance of visuality in their songmaking practice.

Upasana Das (UD): When did you decide that you wanted to start EXCISE DEPT?

Rounak Maiti (RM): KJ (Karanjit) and I have known each other from school, since we were fifteen years old. At that time, I was just starting my music and sound practice, including writing music—they were more folk-inspired. He (Karanjit) was just starting to take photos which were overedited.

Karanjit Singh (KS): Photoshop to the max! I was trying to be Steve McCurry x Raghu Rai—you know the thing.

RM: We became friends over a lot of things we were consuming that have permeated into EXCISE DEPT’s practice—this shared interest in diasporic Indian narratives, colonialism, Sikh history and Bengal history. After we left school, KJ was studying photography in New York while I was in LA studying psychology, where I went deeper into music. Many years later, in 2018 or 2019, I was touring with my band at Magnetic Fields—which Sid was also a part of. KJ met Sid here for the first time. The whole thing started as a bit of a joke because we were just messing around. KJ started saying things on the mic and it was just funny so we thought let's just put it on a beat and release it on Instagram. Around this time the lockdown also happened, so it was like escapism where we were using Instagram as a place to shitpost, share memes and random beats and verses—just spewing nonsense, basically.

It coincided with my desire to make non-indie music, because I had been making indie and alternative music for years. KJ also wanted to make something new using archival footage and the internet. Sabu (Andrew), who I knew from the music scene for many years prior, came in around this time and said, “We could make EXCISE DEPT a public-facing thing, a serious platform to release and perform music and make great films and visuals.” The four of us drove the project in 2022 since ’20 and ’21 were just incubation years of wondering what direction it was going to take. We were going through a lot in our personal lives also at the time. Last year, we started playing shows and finally put the album up!

UD: What made you call it “EXCISE DEPT,” other than—of course—excise departments and their job description, which is to control and be difficult. Also, what made you choose your primary colour as orange?

KS: That is who we want to be—we want to be a difficulty for other people! (laughs) Easy listening? Nah.

RM: There is a friend of ours, Rohan or Dolorblind, who has worked on some projects with us—the cassette, the website, etc. He pointed out the aesthetic of EXCISE DEPT as “government-core,” which I really liked. So that is always how we write our copy and our positioning as taking on this institutional voice, because it gives you an ability to be vague and indoctrinate people. Even the album name SAB KUCH MIL GAYA MUJHE VOL. 1 (I Have Everything I’ve Ever Wanted) is tied to putting forward this idea that we are making something and want everyone to join us in this collective vision.

EXCISE DEPT.

KS: I see it as three government karamcharis (workers/employees) gone rogue—like something has gone fucked in their inner programming. There is no drip, jewellery or fancy sneakers. Just the classic old grey safari suit. (laughs)

RM: I think it is all part of making EXCISE DEPT a collective organisation. Hip-hop is super focused on the face and about branding and wearing cool clothes. Not just to be a contrarian, but I do feel we are not really a hip-hop group. So it is nice to create that distinction with this aesthetic of being a vague entity that is putting out music, art and film.

UD: I did notice the grey suit. Initially I was considering the grey-suited chawkidar (guard) metaphor, considering the only Instagram account you follow is Modi's, but who usually wears that uniform?

KS: Different safari suit colours have a different meaning for what type of security it is. We have seen some people: private security have black safari suits. Some safari suits are tan. What I have seen in political circles is that when politicians travel across cities, they are given escorts, who tend to be local police. They are armed and wear these grey safari suits, guarding a lot of chief ministers. Interestingly, we got our safari suits made from this person in Chandigarh, who makes the safari suits for the security of the Chief Minister of Punjab. I was like mereko yeh same fabric chahiye (I want this same fabric).

UD: Getting into your songwriting practice, you have said that you do not want to be known specifically as a hip-hop group. I have been listening to your album, and compared to the more overtly political and rap songs, some songs like "BILLO" are more on the softer side, while “BIRHADA” is more spiritual. So what genre are you delving into?

RM: We are very much outsiders to the DHH (desi hip-hop). That gives us an opportunity to play with genre as a medium as well. I started playing in a band and making rock songs in college. I discovered production as I was levelling up and then started making electronic music. Excise is some kind of a culmination of everything—hip-hop has always been something I was drawn to since I discovered it in college—I have consumed hip-hop music more than anything else. Listening to Mobb Deep and Kendrick Lamar—it was very formative for all of us. It is very visceral and has an immediacy that other music does not really have. It is a very free-flowing space.

We make and sing all kinds of music, so all of those influences have crept in. KJ has put me on to most ambient music in my life, so “BIRHADA” is very influenced by Hindustani folk and ambient music. It is a genre that we also use in our films. Just for the album storytelling arc, it made sense to begin and end on “KOYALIYA,” which also starts in a very open-ended way, almost like the morning call and “BIRHADA” is the evening. At the heart of Excise, is this very vulnerable, emotional songwriting. Even the hard songs that are aggressive have a lot of vulnerability—it is not immediately obvious because it is hip-hop. But in “BIRHADA,” and also for the future we are making, we are really interested in bringing out this softness and exploring that in relation to the cultural context and music that we want to showcase, creating something that is playful, but also intimate. Though this album is ridiculous, raunchy and weird, it was important to end it on this very soft and inviting note—it brings people into the universe.

Still from their song 'CTRL DEL ALT'.

UD: Talking about the emotional aspect of your music, I think you mentioned in a Rolling Stone interview that you work a lot with the ‘tortured Sikh’ metaphor. It was transformed in “LIFE'S A GAME,” where it is a more light-hearted portrayal. There is a history of Sikhs being looked upon as these great warriors fighting for the British in the First World War, which led to them being stereotyped as loyal, along with the Gurkha soldiers. We see that this notion of Punjabi masculinity is still prevalent in the Indian army and police forces today. How do you engage with this?

KS: Sikhs have always been used like a personal project for the Empire. Even now in America, I would see these ads about Sikhs joining the US Army, and it is something that sardars still aspire to, which is absolutely absurd. I wanted to break that image of Sikhs being hypermasculine, because say the state wants to use you as this militaristic ploy—if it works out, great; if it does not, then immediately you are labelled a terrorist. There is somehow no middle ground for sardars to be shown in any other manner. You are either a comedian that makes people laugh, like “Sardarji ki barah baj gaye” (Sardarji is Screwed) or you are a killing machine—that is what I meant by a “tortured Sikh.” I wanted the lyrics to reflect this sardar that has to constantly evolve and fit into various roles, and at the same time, they are failing. We had “CTRL DEL ALT” that delved into my own personal history. I come from a family that has gone through Partition, and we have a very deep-rooted story in the 1984 crisis in Punjab and with the government dealing with militancy in Punjab. So, I come from a family of victims and collaborators, and that has been a confusing place for me to navigate through, and so “CTRL DEL ALT” was a little bit about that—about being in America and having a racial assault happen. And then “LIFE'S A GAME” was to try and turn it around—the same Sikh person is this weird magician—he can conjure up any reality and a whole new way of being, and we just wanted to play with that idea.

UD: You also talk about how you thrive on schizophrenic viewing in your practice. What do you mean by that?

KS: Visually, definitely—think about the times we are living in, right? You are constantly filling your headspace—one second you are coming across a post about a child’s remains in a shoebox in Gaza, and Ranveer Allahbadia interviewing some Babaji, and then Modiji talking about something. There is no other word I can find but to call it schizophrenic. For us, the visual aspect definitely needed to be that, and it has crept into the lyrics too, which are helter-skelter. They shift from this rap identity of false bravado to being jaded and terrified of what is happening in the world and feeling disassociated.

RM: We wanted the album to capture this wild emotional palette of being pulled in every direction. The album is very restless and does not sit still with one mood for too long because there is always something new to think about—some news, tragedy or trauma that you have to reflect back on. So, the switching between different roles throughout the album was something KJ did lyrically, and then sonically providing those palettes to keep shifting emotionally was really fun to do. That just happened very naturally in the process. Some days would be for a track like “BIRHADA,” and some days would be for a track like “BAARO MAALA.”

To learn more about political histories of music, read Natasha Gasparian’s essay on Johan Grimonprez’s Soundtrack to a Coup d’État (2024), Sagorika Singha’s reflections on the use of viral rap music in Assam at the time of tabling the NRC, Pramodha Weerasekera’s contemplation of music and solidarity in Sri Lanka, Arundhati Chauhan’s album of Maoists’ production of revolutionary songs in Nepal, and Silpa Mukherjee’s essay on disco music and the diaspora. To learn more about artists responding to the schizophrenic nature of the present experience of the world, revisit Anisha Baid’s two-part conversation with artist Abdul Halik Azeez.

All images courtesy of EXCISE DEPT.