Subdued Song of Chaā: On Nistha Thapa Shrestha’s Practice

Clay pots gleaming under the sharp midday sunlight is a signature scene from Thimi, a small city in the Kathmandu Valley, which was once under the jurisdiction of the Kingdom of Bhaktapur before the formation of the state of Nepal. Well known for its pottery and brimming with sustainable knowledge, Thimi was a playground for Nistha Thapa Shrestha. Having grown up here, she recalls stealing clay from potters to play with and the smell of smoke as clay pots were fired. Her photo series Subdued Song of Chaā pays (2024) homage to her hometown and brings to light an untold side of pottery making. Chaā is the word for clay in Nepal Bhasa, the native language of the Thimi locals.

Two potters add colour to the rim of a clay vase.

Shrestha's first conscious exploration of photography started when she was recovering from a broken leg. She began documenting the pattis and pauwas (traditional resting places) around her home, which are an important part of the local identity. This eventually led her to document pottery, and she quickly noticed that women were neither allowed a role in pottery nor were they fighting for a place. “It began as a heartbreak project,” Shrestha shares.

A woman stands in front of a pile of clay yet to be kneaded for pottery.

For generations, men have been the visible face of this male-dominated profession, the ones seen turning clay into beautiful art pieces and utensils as the wheel takes infinite revolutions. Women, on the other hand, are invisible, their stories subdued. Pottery, while beautiful to watch, demands excruciating labour and fiddling with dirt, which was traditionally considered unsuitable for women. Women were thus excluded from the craft itself but continued to be responsible for many behind-the-scenes activities such as kneading the clay, drying pots and putting them into the furnace for firing, thus making them indispensable to the craft itself. Shrestha quotes a male potter, “If it was not for my wife, making pottery and making a living out of pottery would have been challenging.”

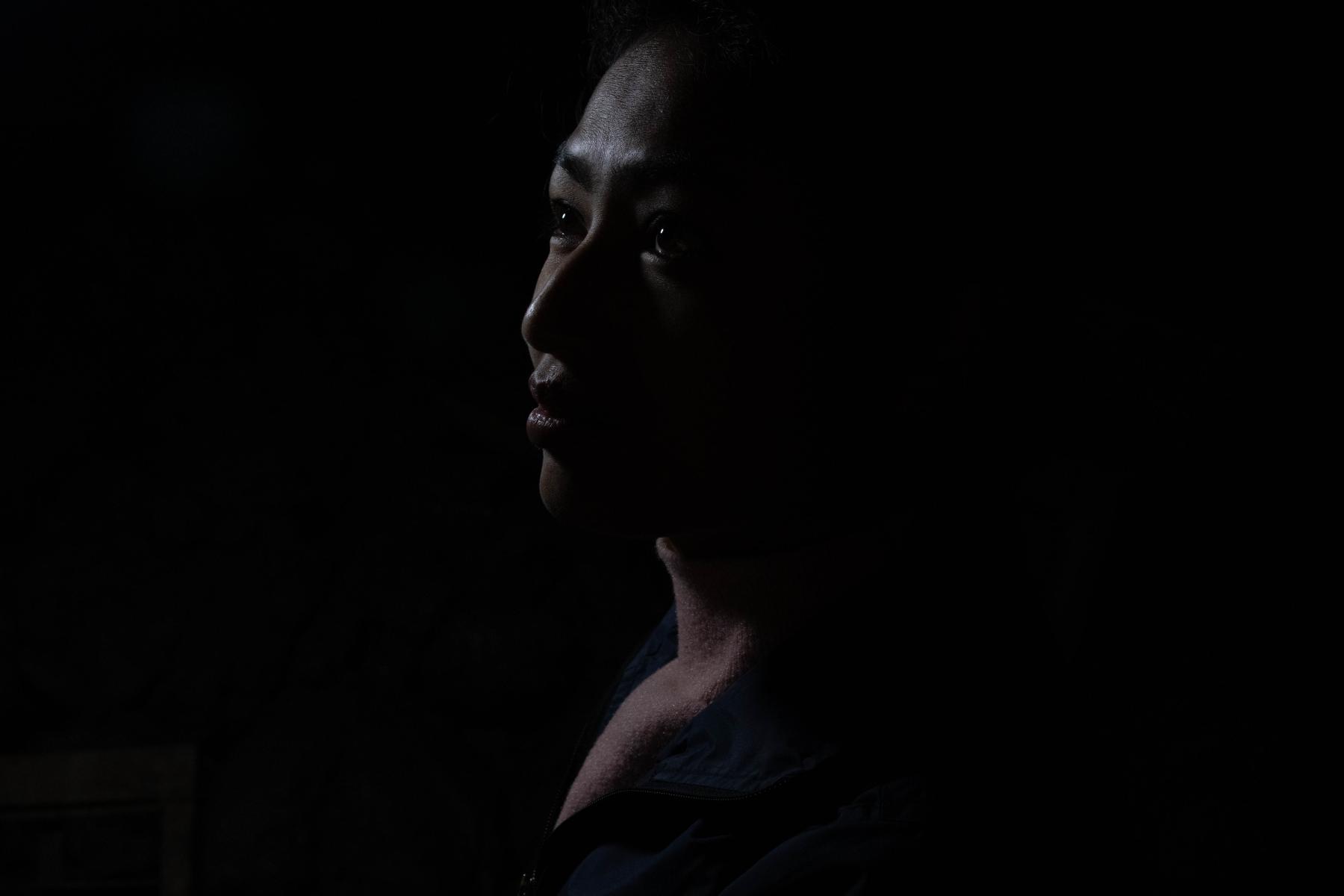

A woman stands in her pottery-making attire. Women work in a quieter capacity yet their contributions are vital to the survival of this indigenous knowledge.

Shrestha recalls a quote from one of the women she spoke to: “I never questioned it—women simply were not meant to work on the wheel.” However, even when women were not actively passed on the craft of pottery, there were women who learnt the art in hiding. Shrestha once encountered a woman who took her deep into her house through layers of courtyards in a traditional Newa (native inhabitants of the Kathmandu valley) household and showed her a diyo (clay lamp) that she had made. “I made this while my husband was away,” the woman had said. Shrestha met men who were supportive of their wives but were still hesitant to have them work in the mud, doing a job that was laborious and difficult.

Sanju Prajapati: “My family believed a young girl should find a ‘respectable’ job, something far from the mess of clay.”

Then came Sanju Prajapati. She became the face of pottery for women and the struggle they have had to put up with in order to inherit the legacy. Like most other families, Prajapati’s family did not want her to learn pottery but she was adamant. Her family could not affort to have both of their children be occupied with studies and Prajapati voluntarily thought pottery to be a way out of school, but had also already fallen in love with the craft. Sanju’s mother carries immense knowledge of the clay. She told Shrestha, “My mother blends haku chaā and gyan chaā (types of clay) in just the right proportions, her hands instinctively knowing if the clay is suited for sharing large handi pots or delicate salies (clay lamps).”

Sanju makes pottery. She believes, “As I shape the clay, it shapes me.”

Shrestha shares that Prajapati is probably the only woman who has been sustaining herself entirely through pottery. During the devastating 2015 earthquake, Sanju’s family home was damaged. Her family had to take loans for the repairs. Prajapati has paid off 80 per cent of the loans through income that she generated doing pottery. She even teaches pottery classes at colleges. As she pushes through the barriers, her family members have begun to see her in a new light. Prajapati’s grandmother, who once vehemently objected to her interest in pottery, now speaks about her granddaughter with pride and admiration.

Subdued Song of Chaā explores the representation of women and indigenous knowledge in a new light, for those outside Thimi, and more importantly, for residents of Thimi themselves. Shrestha’s work not only documents the space women are trying to make for themselves in pottery but also highlights the loss of indigenous knowledge as the practice of pottery is substantially reduced. While old methods are being replaced with new ones, a balancing act of the past and the present continues in the lives of Thimi’s inhabitants as they struggle to keep up with the ancient craft.

A man holding a photograph of his wife and other women making pottery.

To learn more about the intersections of gender and diverse communities in Nepal, read Shranup Tandukar’s essay on Rajan Kathet and Sunir Pandey’s Dhorpatan (No Winter Holidays, 2023), Sikuma Rai’s Come Over For A Drink, Kanchhi (2020) and revisit Sukanya Deb’s essay on Nepal Picture Library’s Feminist Memory Project.

All images are from the series Subdued Song of Chaā (2024) by Nistha Thapa Shrestha. Images courtesy of the artist.