A Feminist Memory Project: Women in the Public Sphere

The Feminist Memory Project, curated by Diwas Raja KC and NayanTara Gurung Kakshapati of the Nepal Picture Library, details the public and political lives of women in Nepal in the twentieth century. The first iteration of the project was exhibited at Patan Durbar Square, titled The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project, as a part of Photo Kathmandu 2018. Subsequently, the project was exhibited at Objectifs–Centre for Photography and Film in 2019, and was part of the 17th edition of the Istanbul Biennial in 2022. The exhibition will be a part of the upcoming Kochi-Muziris Biennale 2022.

In its mission to make rich visual histories accessible to the public, the Nepal Picture Library digitises photographic collections and visual ephemera obtained from personal and institutional archives. Similar to other projects of the organisation, the Feminist Memory Project seeks to create an inclusive history of Nepal that cuts across socio-cultural stratifications to form a people’s social history. This is evidenced in the images featured in the exhibition—images of women’s involvement in socio-political movements to photographs depicting their ordinary lives, travels, letters and domestic spaces.

In a video conversation, Diwas Raja KC discussed the voluminous nature of the exhibition that has become a part of their mission statement. The aim was to make women’s histories visible without making them easily consumable, which has been achieved through the sheer breadth of the material represented. The Public Life of Women was conceptualised for viewership to take place across several days. The sheer abundance of the material resulted in what Raja KC has termed a “spilling out due to an abundance of archives”, eventually leading to exhaustion in the viewers.

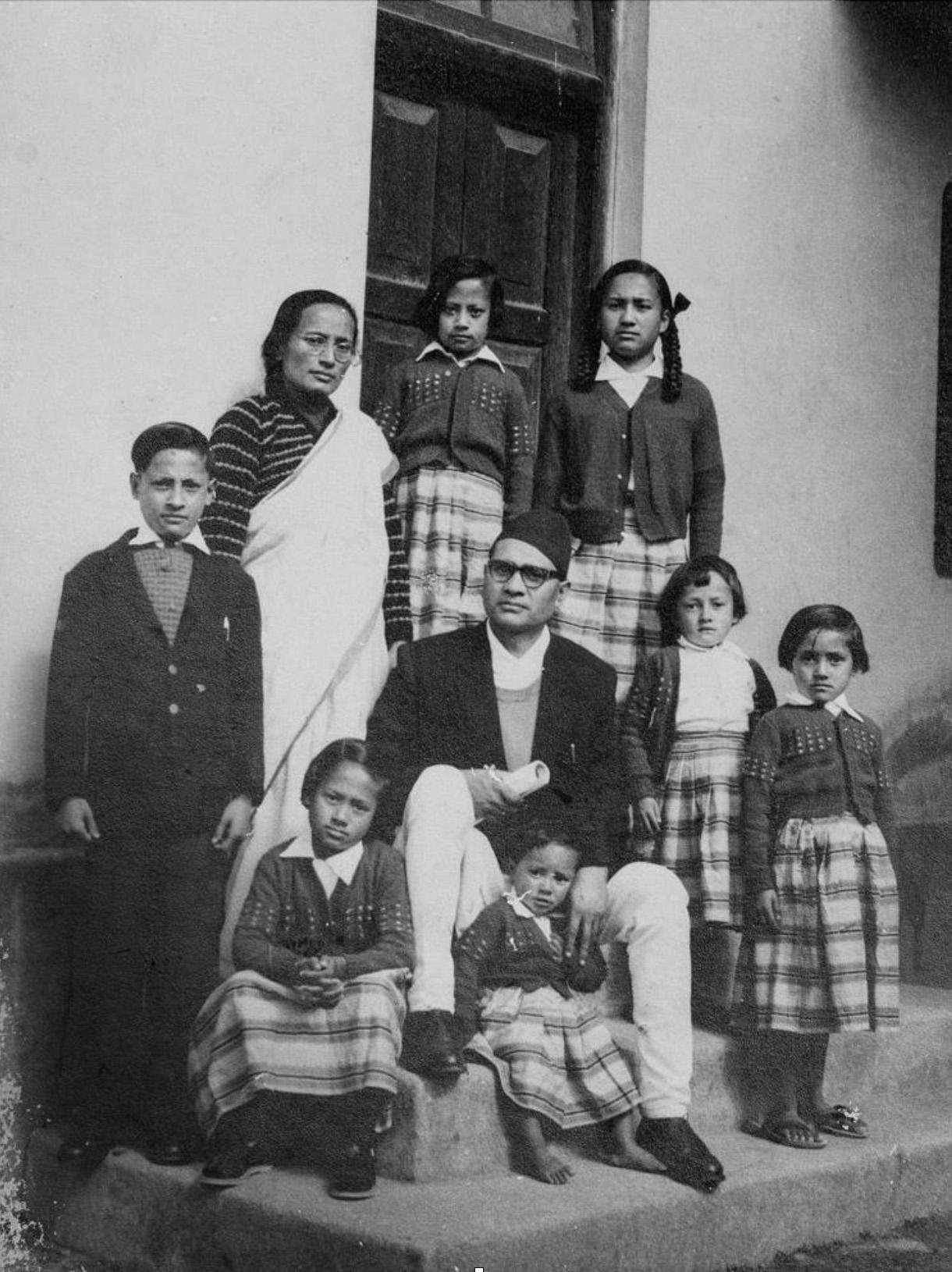

Heeradevi Yami seen with her family. (Kathmandu, c.1961). Image courtesy of the Bidhan Ratna Yami Collection/Nepal Picture Library.

Portrait of Punyaprabha Devi Dhungana who founded the All Nepal Women’s Association. Image courtesy of the Badri Binod Dhungana Collection/Nepal Picture Library

The exhibition harnesses the evidentiary capacity of photographs, highlighting stories of women like Heera Devi Yami who chose a life of political struggle and sacrifice when she married Dharma Ratna Yami. During her husband’s extended incarceration, besides providing for her family, Heera Devi would invite underground activists and the political fraternity into her household. While much has been written about Dharma Ratna, there is little information in the public sphere about Heera Devi. The Bidhan Ratna Yami collection, digitised by the Nepal Picture Library and featured in the exhibition, has shed light on Heera Devi’s contributions.

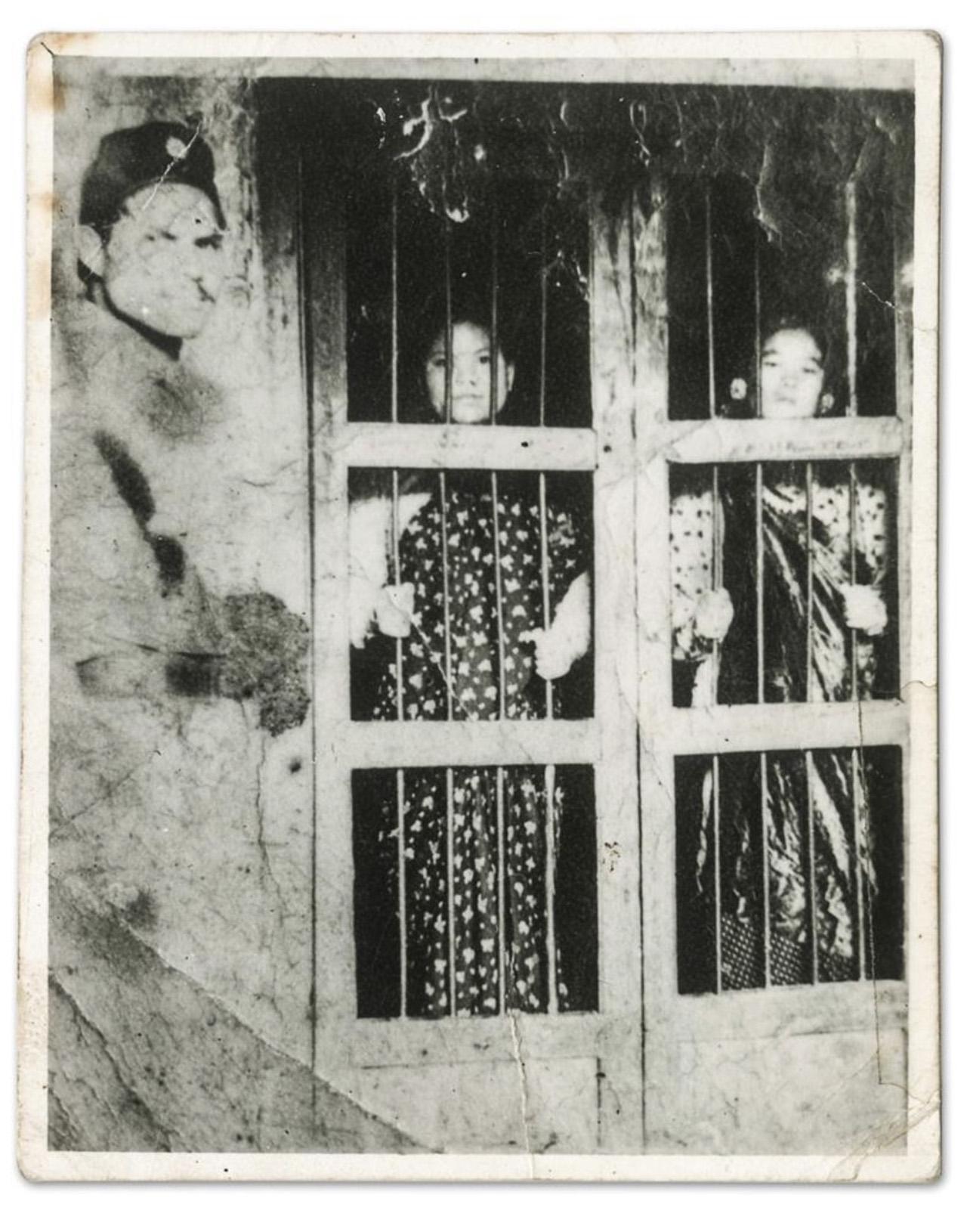

Another significant figure in this exhibition is Mangala Devi, who led a political procession against the monarchic Rana regime and was subsequently jailed when her firstborn was only a month old. She went on to be one of the co-founders of the first Women's Association of Nepal, and she fought for Nepalese parliamentary democracy and civil rights for women in the country. Despite her contributions, Mangala Devi has remained a footnote in mainstream history. Raja KC emphasised that in the twentieth century, when women’s rights to life, education, and work were restricted to a certain socio-economic standing, women’s movements in Nepal harboured revolutionary potential.

Portrait of Mangala Devi. Image courtesy of the Nepal Picture Library.

Prem Kumari Tamang of Nuwakot and Lal Maya Tamang of Dhading, who were put in Dillibazar Prison for opposing King Mahendra’s coup d’état. (Kathmandu, 1961). Image courtesy of the Shanta Shrestha Collection/Nepal Picture Library.

Furthermore, as Raja KC pointed out, another reason for women’s involvement in the public sphere that is often overlooked is that women were not targeted by policemen and could therefore become conduits for organising, relaying information and carrying letters between underground revolutionaries. Stories in the exhibition detail women stepping out late at night to enable this exchange of information, a shared experience between women who became feminist icons. Rashmi Rajya Laxmi Shah was an iconic radical feminist who travelled on bicycles at a time when women were unable to travel freely of their own accord. Shah was an aristocrat who was involved with the feminist organising of indigenous Nepalese women, which is also explored in the exhibition.

Raja KC elaborates, “Women’s own radicalisation and mobilisation at the time were closely tied to their desire for education, literacy and subjective expressions.” This is clearly evidenced in the inception of women’s magazines, chapbooks, and the use of carbon copies and self-publications by underground activists, while in hiding, to circulate their material. Since the 1950s, the exchange of letters, notes, anecdotes, publications, and storage of written material allows us to access this desire to inform and establish a democratic public sphere at a time of autocratic rule in the country, through a “self-conception of their own place in public life”. The magazines and zines produced during this period of struggle and resistance contributed to the creation and dissemination of feminist consciousness and ultimately led to organisation as a part of this radicalisation.

Installation view of The Public Life of Women: A Feminist Memory Project. (Photo Kathmandu, 2018)

To know more about the Nepal Picture Library and its projects, click here, here and here.