Seeing through Censorship: Wakilur Rahman’s Censored Image

For photographer and artist Wakilur Rahman, censorship in Bangladesh is born of the conflict between individual expression and the state’s control of knowledge. His practice deconstructs both of these complex categories, questioning the self’s motivation to censor another body or image. In this, Rahman appropriates the tools of censorship to change the viewer’s perspective to see like the state. He invokes the ridiculousness of assigning a disembodied viewing practice—adopted by the state as the norm—that the citizens of the state are taught to perceive the world around them. These are the ideas explored in Censored Image, created, curated and “censored” by Rahman, and exhibited at Dhaka’s Kala Kendra in 2016.

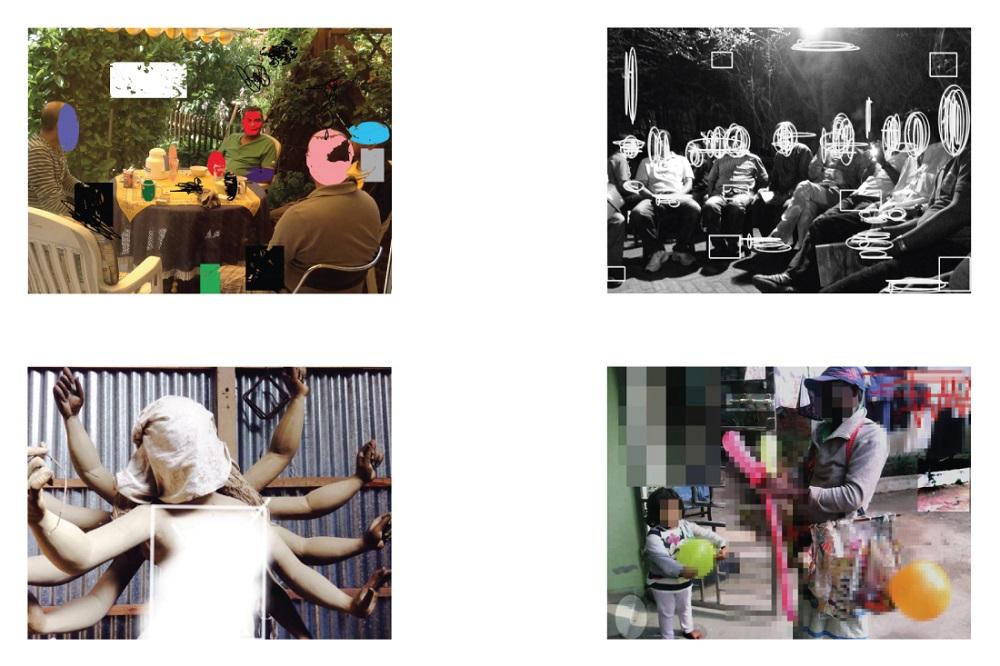

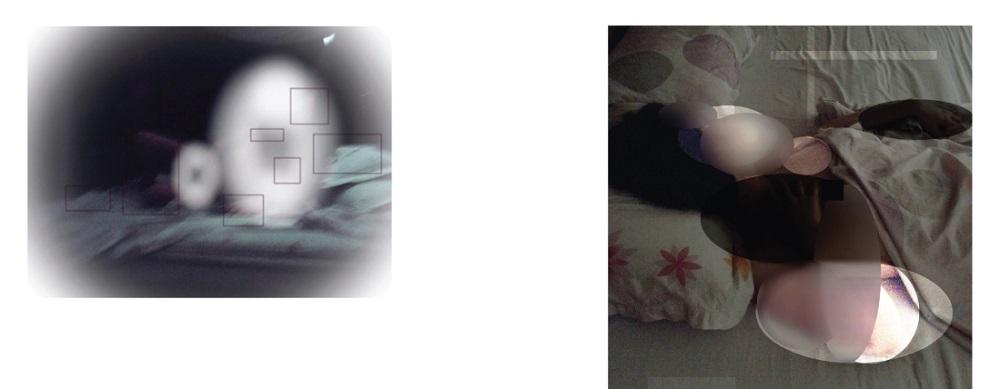

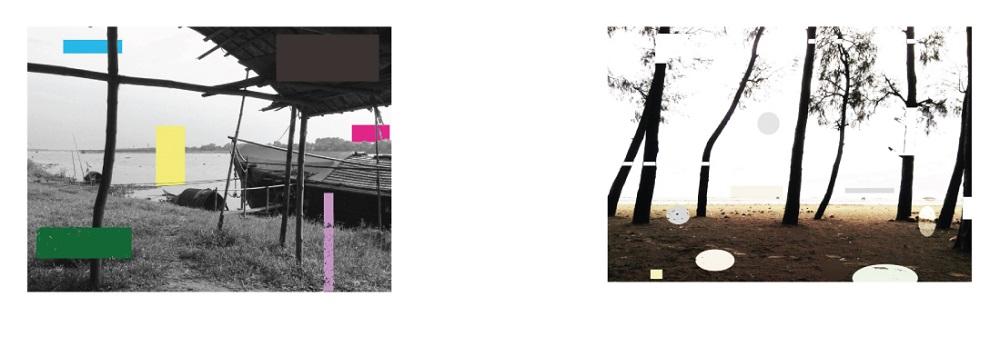

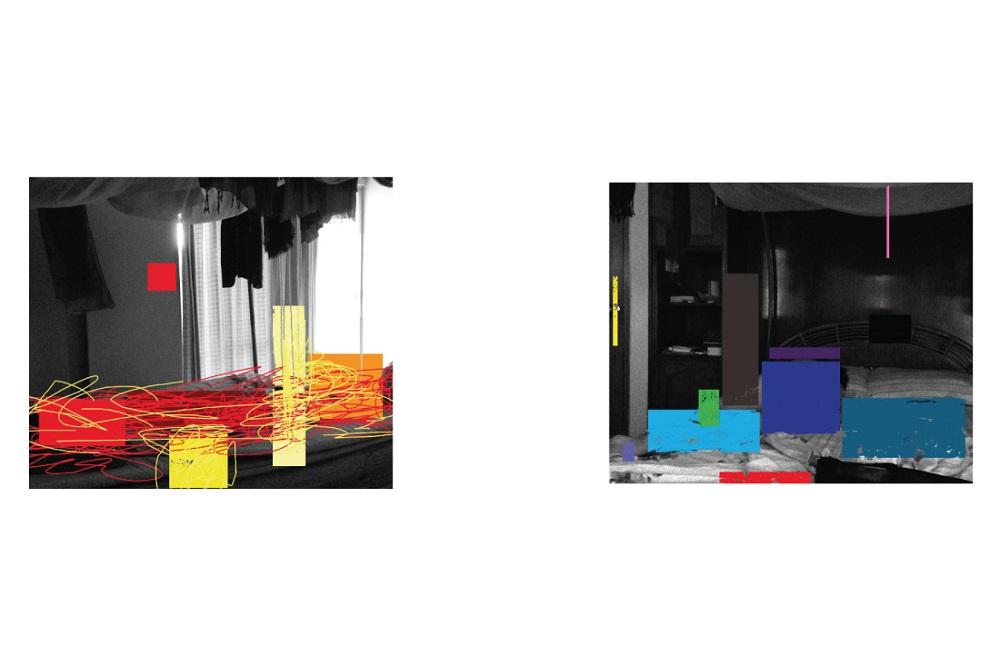

As Rahman highlights, many of his images are “banal”. He sarcastically imitates the state’s gaze through deliberate applications of opaque bands of colour on arbitrary sections of the images. The deletion heightens the paradox of censorship; the viewer is compelled to stare at the empty boxes that seemingly conceal dangerous formations, which may be either politically compromising or erotically suggestive. Along with solid blocks of colour, Rahman blurs, pixelates, shades and scratches the images, employing a whole range of tools to announce the presence of censorship within the frame. When Rahman pixelates what appears to be an ordinary balloon toy, however, the pixelated trace that remains suggests a phallic impression, trapping the censuring impulse in its own fantasies of Freudian repression. The arbitrarily fixed squares and circles also suggest the act of censorship to be an idealistic one, as if the censorious eye is driven by its own need to find geometrically perfect patterns in community image-making exercises, instead of accepting the irregular shapes that democratic decision-making typically takes. The work also signposts the ways in which state infrastructures constantly scramble to find ways of stifling new forms of resistance emerging everywhere—requiring it to become a technological avant-garde, geared towards an essentially conservative impulse. This scramble for control is partially enabled by the expansive world of social media and the ubiquity of internet imagery. Rahman posts a majority of his images on social media sites like Facebook, who have censored or removed some of his content as well. This experience brought about the idea for Rahman to pre-censor the images, a parodic pre-empting of the state of mind that engages in such a task.

Rahman is not the first visual artist to find the act of visual censorship to be an object of interest. Eric Baudelaire’s (sic) (2009) observed a censor patiently at work, blocking out potentially objectionable sections of a text. When the Thai government ordered the removal of select scenes in Syndromes and a Century (2006), the director Apichatpong Weerasethakul altered the censored scenes by using silent black frames, making audiences acutely aware of the censored sections, even if they could not see the actual scenes. The “censored” bits are now an inseparable part of the film print, informing the narrative as much as the plot itself.

Rahman’s work does something similar in reversing the gaze of the artist towards the censorious eye breathing down his neck. Even as paranoid nations aspire to be the all-seeing eye that refuses others’ gaze upon itself, the act of censorship becomes a part of the narrative of Rahman’s work. While the work deconstructs the act of visual censorship, it also suggests the essential role of imagination that censorship can never quite repress, and instead deflects onto other and potentially more subversive projections.

However, not every image in Rahman’s work is acceptably “banal”. One of the images show Noor Hossain’s bare body with the words “Swairachar nipaat jak/Gonotontro Mukti Paak” (“Down with autocracy/Let democracy find freedom”) emblazoned on it. In 1987, Hossain was shot dead by the Bangladesh police, during his protest at Dhaka’s Zero Point against the autocratic rule of H.M. Ershad, which folded soon after in 1990. Rahman removes the radical text from Hossain’s body, deeming it a dangerous slogan for contemporary Bangladesh as well. Hossain’s figure stands in for the resilience of individual expression against the state’s erasure of memory. The image historically suggests the conflicting overlaps between formations of community identity, national identity and individual freedom in South Asia. While Hossain’s martyrdom is celebrated as a national holiday in Bangladesh, under the dark, premeditated manipulations undertaken by Rahman, the provocative nature of his protest becomes starkly relevant for our time as well.

All images from Censored Image (2015–) by Wakilur Rahman. Images courtesy of the artist.

To read more about censorship and artistic responses around them in South Asia, click here, here and here.