Song Narratives: Molla Sagar’s Documentary Films

Film Still from Gonga Buri (2009).

Speaking about the powerful narrative of songs in his documentary storytelling, Molla Sagar said, “If I could sing, I would not make films—music is so dear to me.” An artist, documentary filmmaker and cinematographer, Sagar’s films are dominated by the rural and national histories of daily lives, people’s occupations, protests and changes in Bangladesh.

Sagar’s journey with documentary filmmaking started with O Pakhi (2002), a telling of the culling of migratory birds in southern Bangladesh. Inspired by Ritwik Ghatak’s cinematic ideologies, Sagar’s work explores cultural and ethnic practices that speak about basic human rights and injustices in everyday encounters. His process involves spending time with various communities. He works with them deliberately and unhurriedly, allowing him to gain a certain trust and acceptance. Narratives of the everyday are documented and told through sounds and songs. The pace and depth of rural life that depends on nature’s cycle, water and human’s power are some of the recurring elements in Sagar’s films. There is an acute awareness of watching with the camera. Sagar feels that the documentary approach helps frame a life. For the artist, it is this style that makes a “true film”—where the credibility and realness of his subjects are preserved with a certain sense of intensity and authenticity.

O Pakhi (2002).

Over an email exchange with Sagar, he revealed his purpose of making films:

“…to talk about issues or events, about the people who speak to the larger interests of society and against injustice. I try to blend in with the community completely. It takes time, but it makes it possible to move forward with the pace, texture and depth of their lives and feelings. My films’ narratives are created by feeling the way people live their lives.”

Their faith makes way for an allowance of hope and trust. This pushes the artist to translate and represent their narratives with a sense of moral responsibility as a filmmaker.

Sagar screens his films in villages and cities to allow for larger audiences to view them. He ensures that those who were a part of the films have the chance to watch them. The artist’s growing relationships with these communities is evident from the first screening of Dudh Koyla (Coal-Milk, 2009). When this story—about the Phulbari coal mine of Bangladesh—made its public debut, it drew an audience of over 40,000 people, most of whom belonged to the mining community itself. Responding to this, Sagar said, “They see everything they want or get on the screen, and (in the process) feel important. I got that reflection from them. That is success for me.”

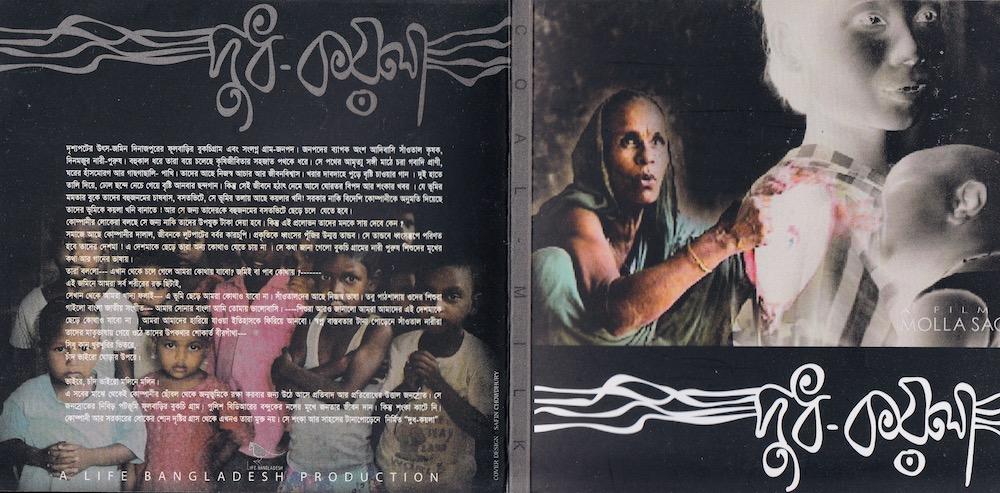

Poster for Dudh Koyla (2009).

Talking about the translation of feeling from sharp camera frames and movements to sound as a primary narrator, Sagar said,

“Thoughts, philosophy, joys and sorrows of the people of Bangladesh have been expressed in songs from the very beginning. Hence, songs become a very important texture in scenes to convey the people and region where song is a part of their lives and not a different entertainment medium. It conveys a lot about the overall thinking of people in the region.”

Folk music appears alongside water and nature, the main sources of income for people as seen, for instance, in Dudh Koyla (2009), Gonga Buri (2009) and The Hilsha (2012).

Gonga Buri (2009).

With people and nature as the central protagonists in his films, Sagar addresses the struggle for the basic survival of communities whose lives are controlled by brutal human power players in various occupations of rural Bangladesh. Dudh Koyla begins with a scene of an open farm field followed by the the line: “Here is a coal mine. But who comes first? Coal or human?” The indigenous Santals of Phulbari, around whom the film is made say, “We are a community who love our land with every drop of blood.” Open fields, dance, animals and joy in the rain shrivel into resistance and the fear of the rise of poverty. Chronicled by Sagar’s lens, these conversations take place in the intimacy of people’s homes and kitchens. The subjects openly share their worries with the camera thereby revealing the trust they instil in the artist. Sagar tugs on the viewers’ emotions with shots of animals, smiling children and nature—all of which hold hope for future that may currently seem bleak.

Dudh Koyla (2009).

To read more about Bangladeshi cinema, please click here and here.

All images and videos by and courtesy of Molla Sagar.