Sikander Begum and Her Royal Court: Looking at the Waterhouse Albums

In 1862, when Second Lieutenant James Waterhouse (1842-1922) of the Royal Bengal Artillery arrived in the city of Bhopal, the paramountcy was in the middle of a celebration. The Nawab Sikander Begum of Bhopal had been recently appointed to a newly instated Order of Chivalry by Queen Victoria as the “Knight Companion of the Order of the Most Exalted Star of India.” The Order was created after the revolt of 1857 to honour Indian princes and chiefs for their loyalty and support to the British troops in quelling the rebellion. As the only woman among a list of twenty-four men to have received this honour, Sikander Begum was a source of intrigue in the nineteenth-century British colonial world. James Waterhouse, a photography enthusiast who would eventually head the Photographic Department of the Survey of India and pioneer the development of photomechanical printing, was specifically instructed as part of a year-long photographic secondment across Central India to capture an official photographic portrait of Sikander Begum for imperial records.

Begum of Bhopal with Musicians at Her Court.

Under the aegis of the new British Raj, the colonial state identified the chiefs and rulers of Indian princely states as crucial nodes for accumulating power over the region. The Queen of England in her 1858 proclamation recognised the authority of rulers of princely states and guaranteed that their sovereignty over their principalities would remain intact under the larger, umbrella sovereignty of the British Empire. The Begum and her counterparts in other princely states, thus, were both sovereigns and subjects of the Crown at the same time. This placed the princely states in colonial India in a privileged, yet precarious position within the British Empire. Sikander Begum’s unique contribution to this period’s history is the way in which she negotiated with the Queen and the local authorities alike to uphold her claim as a female ruler over a major kingdom in Central India, despite the challenges presented owing to her gendered identity.

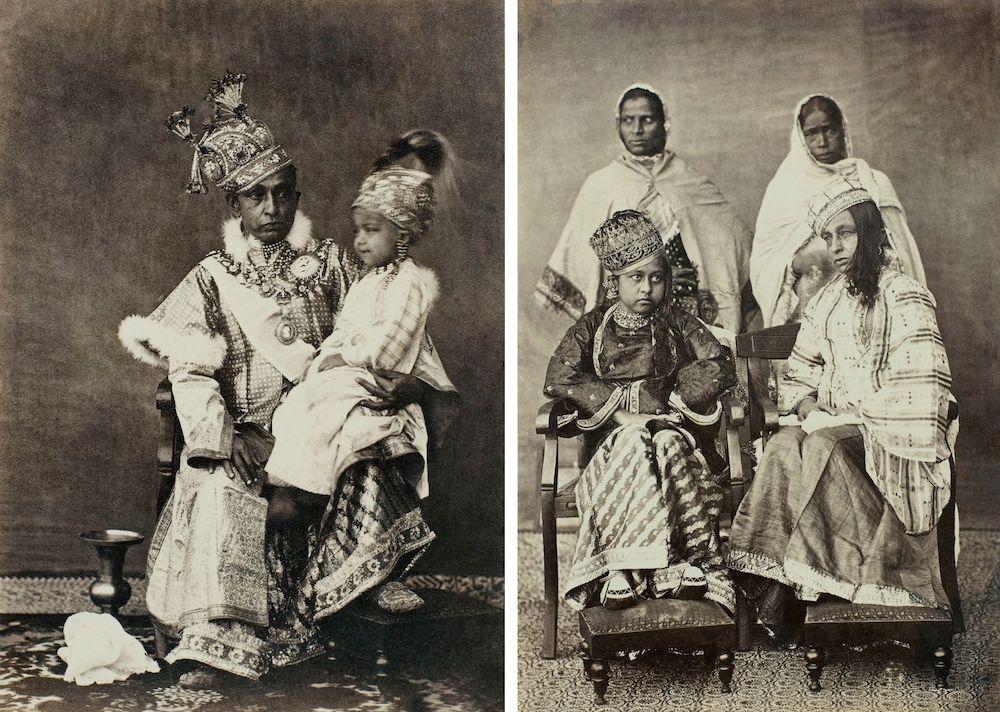

Flaunting a Costume Fit for a Wedding. (Left-Right): Bibi Dulhan, Shah Jahan Begum and Nawab Sikander Begum.

An iconoclast and pioneer in several regards, Sikander Begum met Waterhouse with an enthusiasm for the camera that matched his own. Not only did she get her official portrait taken, she also offered Waterhouse an insight into the sartorial splendour of the royal court of Bhopal. Native women’s photographic portraits were far and few at this time. Considering the widespread practice of purdah in both Hindu and Muslim traditions in colonial India, Waterhouse had so far failed to photograph the Indian noble-woman. When he conveyed this to Sikander Begum, she presented this photographer with myriad perspectives into the interior lives of the upper class Indian women—duly flouting the purdah in ingenious ways.

Left: The Begum with Her Granddaughter.

Right: The Begum in a Casual Sitting in Her Inner Court.

Much like the outfit montage characteristic of modern cinema, one finds in the photographic collection produced by Waterhouse a series of photographs of Sikander Begum and her royal court in a variety of costumes—regal, courtly, bridal, as well as what the Begum would wear while relaxing with her granddaughter in the inner court. This collection, thus, presents a peek into the immemorial portraits of a formidable ruler and a politically astute woman in all her pictorial glory.

1.jpg)

Left: Nawab Sikander Begum and Her Daughter Shah Jahan Begum Dressed as Marathi Women.

Right: Another Staged Scene from the Inner Court of the Bhopal Royal Family.

Anton da Silva, the Begum's Physician.

To read more about early colonial photography, please click here and here.

All photographs by James Waterhouse. Bhopal, India, 1862. These images are part of the Waterhouse Albums Volume I and II courtesy of the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts, New Delhi, India.