Facing the Earth: On Tareque Masud’s Adam Surat

Sultan’s enigmatic figure looms large over the documentary. His daily routines, isolated existence in a dilapidated haveli and intimate dedication to representing the hidden or "inner strength" of the farm labourers of his country reflect a unique form of commitment that contrasts strongly with the increasingly urban-centric, networked, professional artists of late twentieth-century South Asia.

Tareque Masud’s first film, Adam Surat (The Inner Strength, 1989), was a documentary that he shot over seven years in the environs of the decolonial painter Sheikh Mohammed Sultan’s home in Narail, in the Jessore district of Bangladesh. Ostensibly a biopic on the painter, the film transforms its subject into a conduit through which the viewer may approach the vigorous life and labour of the peasant communities of rural Bangladesh and perceive their unity with the soil. Like Sultan’s own project of returning to the roots of the idea of Pakistan (and then later, Bangladesh) as a fundamental political demand for peasant freedom; Masud’s film reminds viewers of the unfinished nature of the traumatic struggles for autonomy and nation-building even after nearly two decades of the formation of Bangladesh.

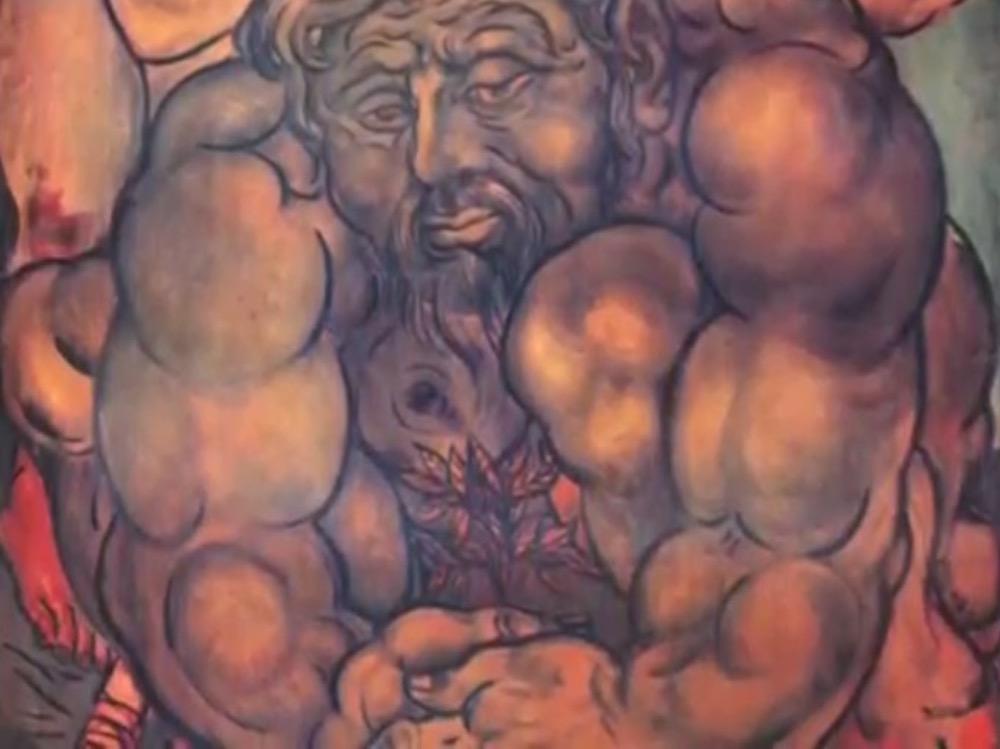

The earthy forms and exaggerated physical aspects of the figures foreground the enactment of the painter’s will to representation on the canvas. In these figures, one finds an abstracted presence of the painter’s own subjectivity, relating the human bodies in organic harmony with their worked environments.

Masud’s voiceover narration stitches a brief overview of Sultan’s peripatetic life across undivided India in the 1940s and then, onto Europe and America. He only settled into his rural idyll in the 1950s and started developing his own idiom along with other major East Pakistani Bengali artists of the time like Zainul Abedin, Safiuddin Ahmed and Quamrul Hassan.

His notoriety as an eccentric recluse who lived with a revolving cast of cats and chickens in an overgrown ruin of a stately mansion, looked after by a widow and her daughters, spread quickly. In Masud’s film, we recognise his androgynous figure to be a source of confusion for some. Shots of his long, lustrous hair, combed everyday by his caretaker/companion (who also assists him with his ablutions), become channels of voyeuristic access into the solitary life and habits of the artist. Masud does not broach the question of sexuality, even though Sultan’s paintings express that particular variety of earthiness that can only be described in erotic terms. The bulging muscles and rounded breasts of his male and female subjects display an ambisexual interest in joining their human erotic potential in natural harmony with the land and its need for physical toil. Described by art critics as a fantasy of vitality that is projected onto the bodies of farm labourers, his paintings use these exaggerated human forms to suggest the strength of the community as embedded in their traditional practices of labour and intimate knowledge of the land. Sultan uses it as an argument against the importation of expensive technological supplements—whether weed-killers or artificial, high-yielding varieties—which can damage the soil. His figures resemble those out of a Michelangelo painting or a William Blake engraving, deliberately imposing their scale upon the viewer. Sultan used locally sourced and ground colours and painting materials to avoid the prohibitive costs of standard art materials at the time. With Blake, he also shares a dissensual critique of the normative powers of modernity and its promise of bounty.

Moving away from the alienated landscapes suggested by industrial growth—an objective that their neighbour, India, was enthusiastically adopting in its post-independent plans of development—Sultan focused on the life-giving, environmentally related world of rural Bengal. He emphasises his interest in depicting relationality between humans and nature—dissolving their essential differences—and rejects the geometric, harsh edges of modern abstract art. In a curious reversal of older orientalist critiques of the excessively “decorative” nature of non-Western art, he deems modern abstract art as decorative, especially for the purpose of designing urban living rooms.

Masud’s film communicates the philosophy of the artist’s late, settled life well; but obscures his formative influences. There is a somewhat simplistic reduction of his practice to the ideal of harmonious agrarian relations. Elements of his work find their ideological roots in liberation theologies of the past, like the Khaksar Movement begun by Allama Mashriqi. An anti-colonial movement, it focused on self-transformation among the depressed Muslim communities of India so that they could evolve a more worldly political ethic of cooperation with others outside the community. Khaksar, pointing out the body’s (including the self) origin in dust, aimed to cultivate a new humility around the question of identity. It was one among several competing ideologies of Muslim reform that galvanised the body politic of the community in the decade before partition.

The cosmopolitan art critic and poet, Hasan Shaheed Suhrawardy was also influential in getting Sultan admitted to the Government College of Art and Craft in Kolkata (which he quit without finishing). These influences are largely ignored in Masud’s overview, even though they are visible in his dusty palettes and the orientation of his hyper-local engagement, which was arrived at after a cosmopolitan encounter with the world at large. It was an important decolonial trajectory that several artists performed at the time, leading writers like Nirmal Verma and Namvar Singh to suggest that in the “East” there was no choice but to go through Europeanisation in order to eventually reach beyond it.

Masud’s film aims to give us a sense of the painter’s semi-exilic life of pastoral bliss and his commitment to representing the labour of the local peasants. We witness his ability to perform the law of descent where one deliberately courts imperfections—whether moral or physical—to challenge colonial and totalitarian emphases on perfectionism and reject normative tracks of worldly aspiration. By embracing a trajectory that is resolutely opposed to the triumphalist, postcolonial narrative of arriving at the centre of the colonial metropolis (like a VS Naipaul), having mastered the tools of the master; Sultan’s practice of life and art becomes exemplary for thinking a new, decolonised, organic community into being.

To read more in our series on documentary films and contemporary art, please click here and here.

To read more about Bangladeshi cinema, please click here, here and here.