Visibilities, Mobilities, Positionings: Photography Across Spaces of Exhibition

The “Exhibitions and Touring” panel as part of the last day of the conference Concerning Photography brought together curators, writers and art historians who presented papers on key spaces of exhibitionary practice. The panel looked at how these displays, workshops and magazines galvanised the medium of photography through affective, socially-engaged practices, enquiries, activations and collectivities. Revisiting two papers within this panel, namely the presentations of Ruby Rees-Sheridan (paper presented by Carla Mitchell) on the Half Moon Photography Workshop and Catlin Langford on Signals, The Festival of Women Photographers, I write on their close readings of these exhibitive formats, their feminist visibilities and the challenges to mainstream photographic practice that they outlined.

In their presentation on behalf of Ruby Rees-Sheridan, Carla Mitchell looked at the influential role of the Half Moon Photography Workshop (later known as Camerawork) in the development of socially engaged photographic practice, with a particular focus on the manner in which it was received. Between 1976 and 1984, the Half Moon Photography Workshop (HMPW) prepared a pioneering set of touring exhibitions that were central to democratising the practice and exhibition of photography. They persisted through the years with a motto that asked, “Not is it art, but who is it for?” From Daniel Meadows’ photographs of Lancashire cotton mill workers to Susan Meiselas’ images of the Nicaraguan revolution, and the 1983 exhibition on the death of Colin Roach in police custody; these exhibitions provided alternative perspectives on political activism, feminism and working lives. Rees-Sheridan’s paper drew attention to the invention of laminated panels that assisted in the dissemination of photography and its spaces of exhibition beyond established cultural institutions. These panels spearheaded both adaptable formats and effective damage control, and became critical for affordable, transportable exhibitions. This played a crucial role in showcasing an emerging generation of politicised photographers, facilitating their reach to a very wide range of audiences—some of whom were viewing photography in exhibitionary contexts for the very first time.

The non-traditional approach adopted by HMPW worked to assert a more dissipated status of photography, reiterating it as a socially transformative tool. It sought to break the mold of top-down appreciation that tended to overwhelm and overshadow local audiences that were wishing to learn and grow. Rees-Sheridan’s paper foregrounded the comments book as a starting point for her enquiries into the reception of these touring exhibitions. Due to very little documentation otherwise, the comments books served a rare and fascinating record of the impact of the photographs on display, taking shape almost like a heated Facebook thread. Retaining the democratic texture of HMPW to begin with, the comments books were an unmediated space for viewers to express themselves, a valuable counterpart to the Camerawork magazine. Another key aspect of Rees-Sheridan’s paper was the fact that she chose to spotlight certain themes that HMPW brought to the forefront with their focus on expanding to accommodate socially-engaged practices. These new themes culminated in exhibitions such as White Hot Light: Story of a Home Birth (1982) by Karen Michaelsen, which presented a feminist critique of medical births in hospitals, reclaiming ground from mainstream reporting on women's experiences. Giving a glimpse of the comments book from this exhibition, Rees-Sheridan recounted noting the relief and gratitude expressed by women viewers who visited the exhibition.

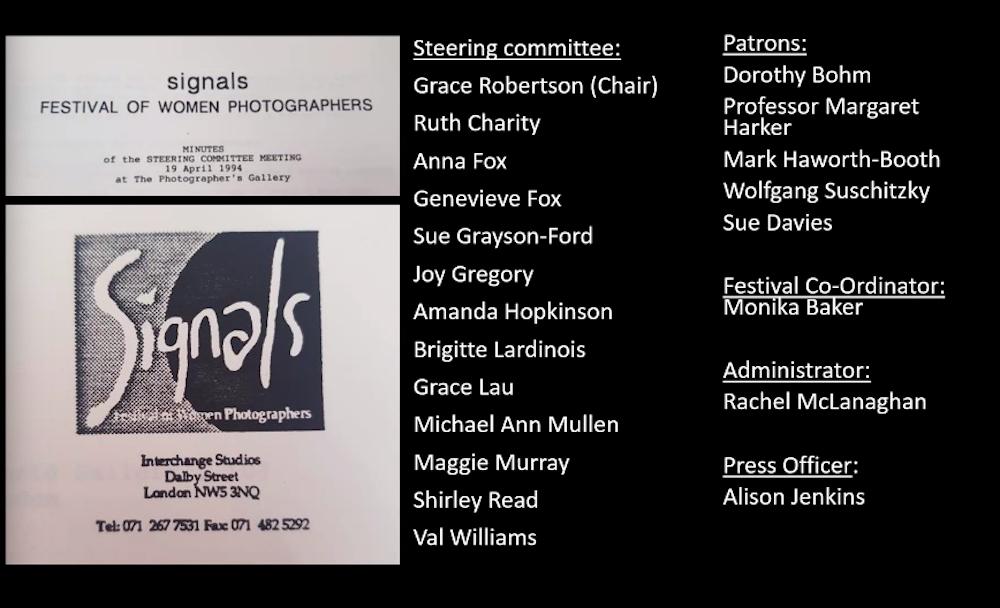

A presentation slide from Catlin Langford’s paper listing photographs of the minutes of the meeting held by the Steering Committee for Signals in April 1994, with the names of the members alongside.

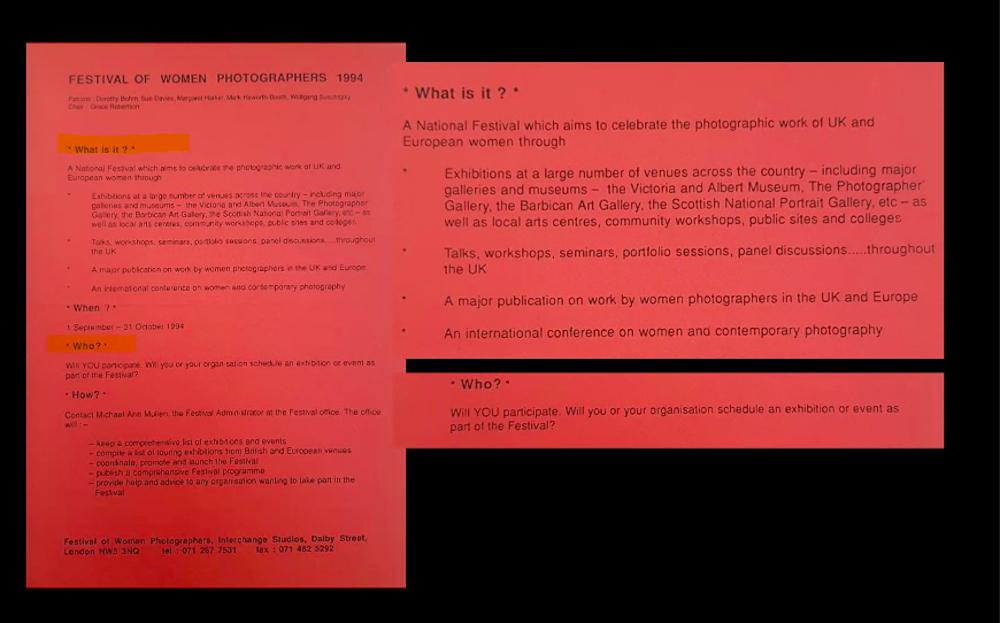

Reading the prominence, precedence and radical proposition of Signals, The Festival of Women Photographers, Catlin Langford chose to trace the rising curatorial interest in photography in the 1990s in her paper. In September and October 1994, close to 300 exhibitions and events were held throughout the UK and Ireland, united in their focus on women photographers, aiming “…to highlight the breadth and diversity of current practices.” The festival sought to challenge the male domination of photography and address the exclusion of women in both histories and display. Exhibitions and events were held in Sunderland, Salford, Herne Bay, Newport and Dumfries, among many others, and the festival was upfront in its inclusion of regions and an avoidance of London-centrism.

“If the idea of a festival devoted to women photographers fills you with dread—all strident feminist ideology and questionable exclusivity—the nationwide event Signals, coming your way soon, promises to be a pleasant surprise,” so said a review of the 1994 Signals: Festival of Women Photographers. During the panel discussion at the end of the session, Langford addressed the fact that feminism was not a direct positionality adopted by the festival. However, simply the extent of the exposure it was affording women photographers was enough to put people on edge. Criticism was rampant, particularly in terming a number of the works “amateurish.” Even though the festival did have a record number of amateur photographers, the word was often used derisively to describe work by women practitioners. Representing amateur works was a conscious decision, and was very much about exposing the multifaceted nature of women's work in photographic practice. The festival showcased photographers from Edwardian studios, vernacular photography as well as female photojournalists, continuing to emphasise the inarguable fact that women have an undeterred, unfettered space in the history and expanse of photography.

A scan of a pamphlet detailing the initiative of Signals, circulated to invite and elicit regional participation from women photographers across the country. The committee received numerous proposals, and being part of a move to represent a wider section of the population meant more access to funding. (Presentation slide courtesy of Catlin Langford.)

In many ways, the 1994 Signals festival represented a groundbreaking move towards a more inclusive and collaborative photographic landscape. As curator Val Williams noted, it existed to “…attract the attention of those curators, editors and funders who make the decisions about who, and what, gets seen by a wider public.”

The phenomenon of viewing and understanding art—and what constitutes a definition of art—has grown to an unprecedented scale with the proliferation of spaces and formats of exhibitions including biennales, fairs and other festivals. Yet with only a 5 per cent shift in the representation of women artists and photographers in the present day, we are urged to think of what might be necessary in the moment and how to create it.

To read more about the conference Concerning Photography, please click here, here, here, here and here.