The Artist as Medium: On Himmat Shah’s Acts of Creation

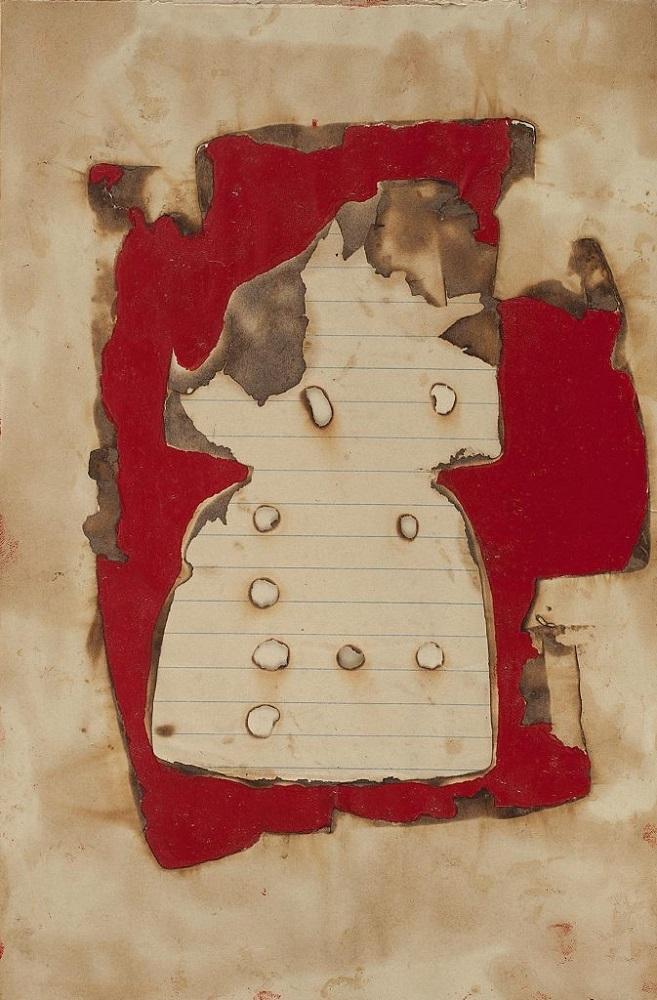

Untitled. (Himmat Shah. 1962. Print and burn marks on paper, pasted on paper.)

The working life of Ark Foundation Asia Arts Vanguard Awardee Himmat Shah traces the ways in which the artist has dissolved himself into acts of creation. The elements of biography, self, personality and the historical tools narrating the formation of these human categories get subsumed into encounters with material, form and experimental craftwork—all describing a continuous arc of becoming something other than what was there to begin with.

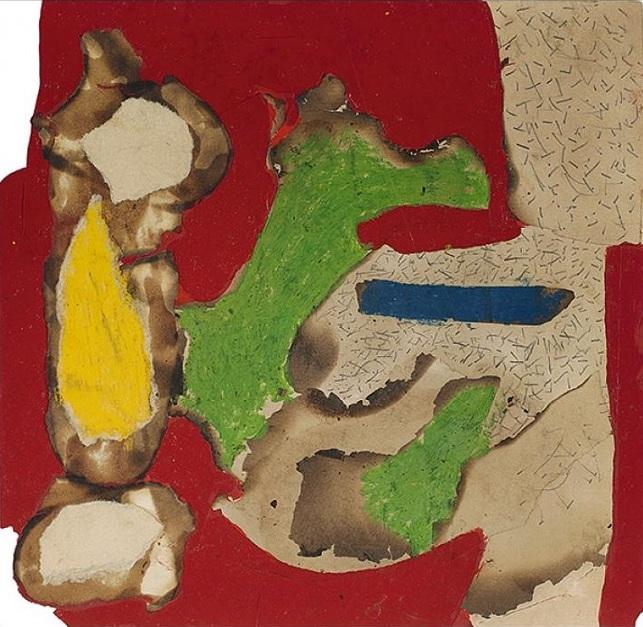

Shah’s work explores the possibilities of producing artistic objects by eradicating one’s subjectivity and rendering it open to the implications of a medium shaped by cultural history. Instead of drawing solely upon his own biography—one that is full of both hermetic stillness and a state of being itinerant—Shah’s method brings him closer to constructing a modernist response to some of the most enduring media practices in South Asian art. His use of clay, terracotta-making techniques and slip-cast sculptures deliberately evoke the limitations and curiosities of a pre-modern artisanal worker. Shah, however, has also produced a delicate oeuvre of burnt paper collages. This series of work illustrates his alchemic process of introducing the discarded remnant of the past into the artificial compound of modern time.

Untitled. (Himmat Shah. 1962. Graphite, pastel, enamel and burn marks on paper, pasted on paper.)

Originally from Lothal in present-day Gujarat, a famous archeological site dating back to the Indus Valley Civilisation, Shah currently lives and works in Jaipur, a place that evokes the imagination of the planned city of Harappa. As author Suzanne McNeill writes, “The principles that shaped Jai Singh’s showcase city were probably formed at the same time that Harappa was established.” There is a spatial continuity that is both absurd and illuminating in the context of Shah’s unique body of work, often described as evoking the shorthand for a civilisational aesthetic.

The burnt paper collages were exhibited as part of Shah’s now-famous show with Group 1890, a rather short-lived artists’ collective founded by his contemporary Jagdish Swaminathan, in 1963. Describing its origins, curator Alka Pande writes,

“In the early 1960s, at a friend’s workplace, Shah playfully burnt some holes into the paper with a cigarette. Soon, he created the aesthetically motivated burnt paper collage with delicate burnt edges and dispersing ash-dust. He exhibited them at the Lalit Kala Akademi in 1963. These warm compositions contributed to his early modernist-bent: layering, superimposing burnt paper and contrasting it with coloured paper.”

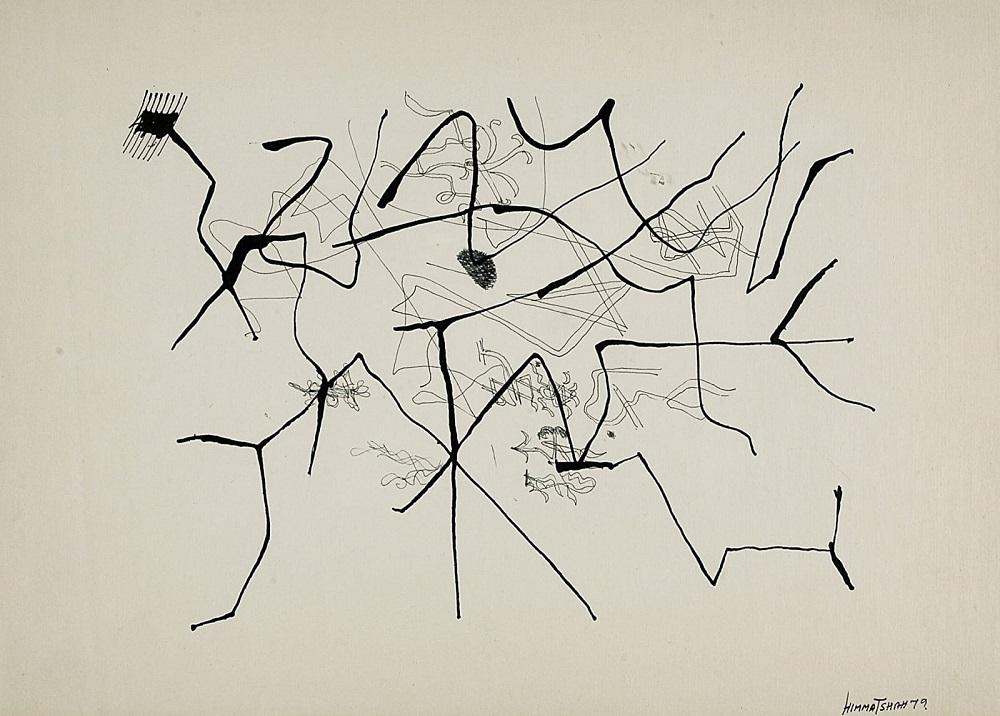

Using glue, printed paper and consciously brushed bands of paint as frames for the charred remains, Shah pushed the language of collage-making by dramatising his casual act of creation through deliberate destruction. The collages represent something against the impulse to draw, to doodle—as Rabindranath Tagore did—to create a garden of impenetrable forms within a field of text. Instead, they describe the difficulty of creating a patchwork of signs from the ashes of a grand, but fragmented, civilisational aesthetic.

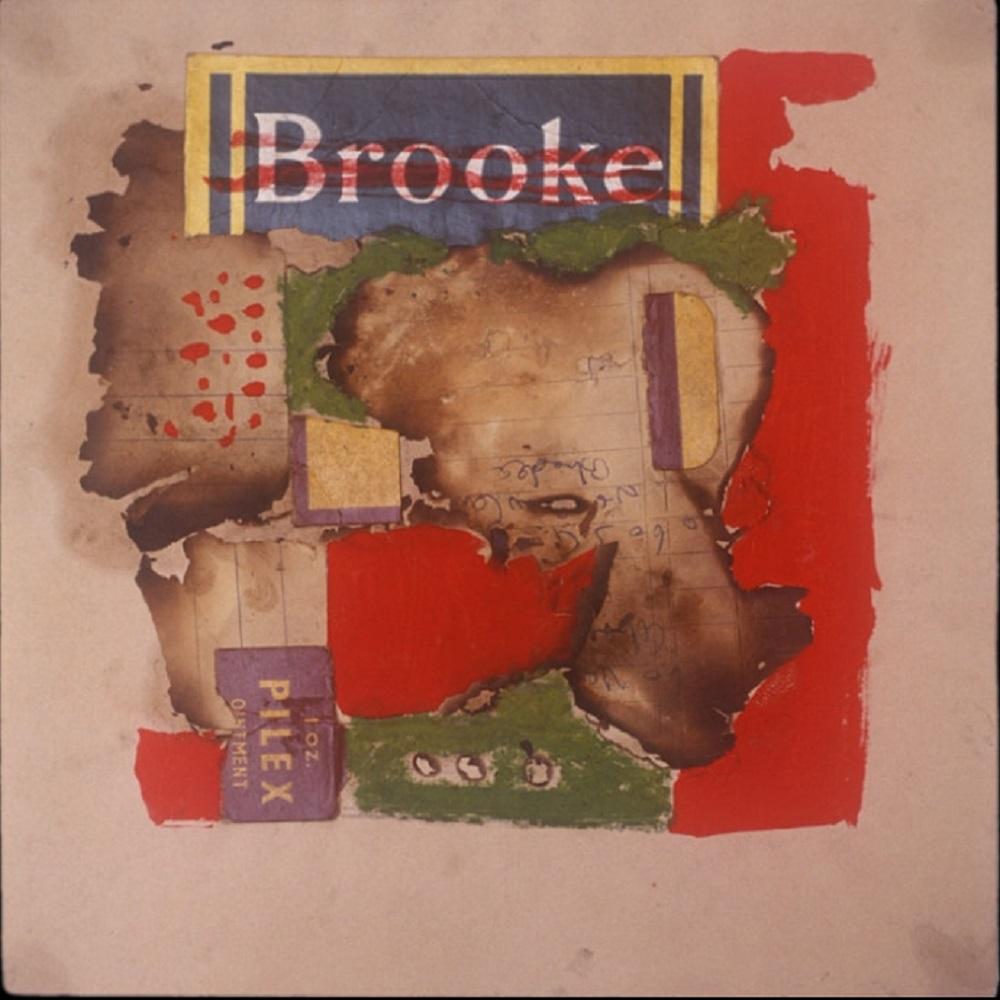

Using material from contemporary print magazines or advertisements like the household brand Brooke Bond, Shah worked on developing multiple idioms with his burnt paper collage, making them an agent of creation, rather than suggesting a singular mode for producing a fixed, even nihilistic, artistic effect.

As critics have noted elsewhere, the collages bear the trace of Shah’s more famous work comprising sculptures and terracotta. Responding to “sensory heat and touch” remains one of his more identifiable marks. Recalling similar sensations in his burnt paper collages, Shah also invests it with oblique passages from postcolonial print history. These help to heighten the temporal conditions of their creation and introduce a strain of dark humour to his work. The coloured labels are drawn from ordinary household brands such as Brooke Bond, but also Pilex—a relieving agent for haemorrhoids. Scribbled figures, distorted lines and drips of crimson paint suggest a variety of (sub)-textual possibilities, as if in a weekly magazine that reduces every event to a formally banal “item”. The charred remains, ultimately, do not signify any heroic act of recovery. When shown in exhibitions, they are usually placed in vitrines due to their fragile surface and construction, always tending toward ashes. The fragments of graphic, advertising prints, allow Shah to insert the matrix of modern life into older modes of organisation, even as these efforts are surrounded by the possibilities of loss and breakdown.

Untitled. (Himmat Shah. 1979. Pen and ink on paper.)

All images courtesy of the artist.

To read more about the work of the honorees of the sixth edition of the Asia Arts Game Changer Awards India, please click here.