To Measure a Fold: Installation Instructions in Mrinalini Mukherjee’s Archive

This is the final instalment in a four-part series of conversations around the Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive with archivists Noopur Desai and Pallavi Arora from Asia Art Archive, India.

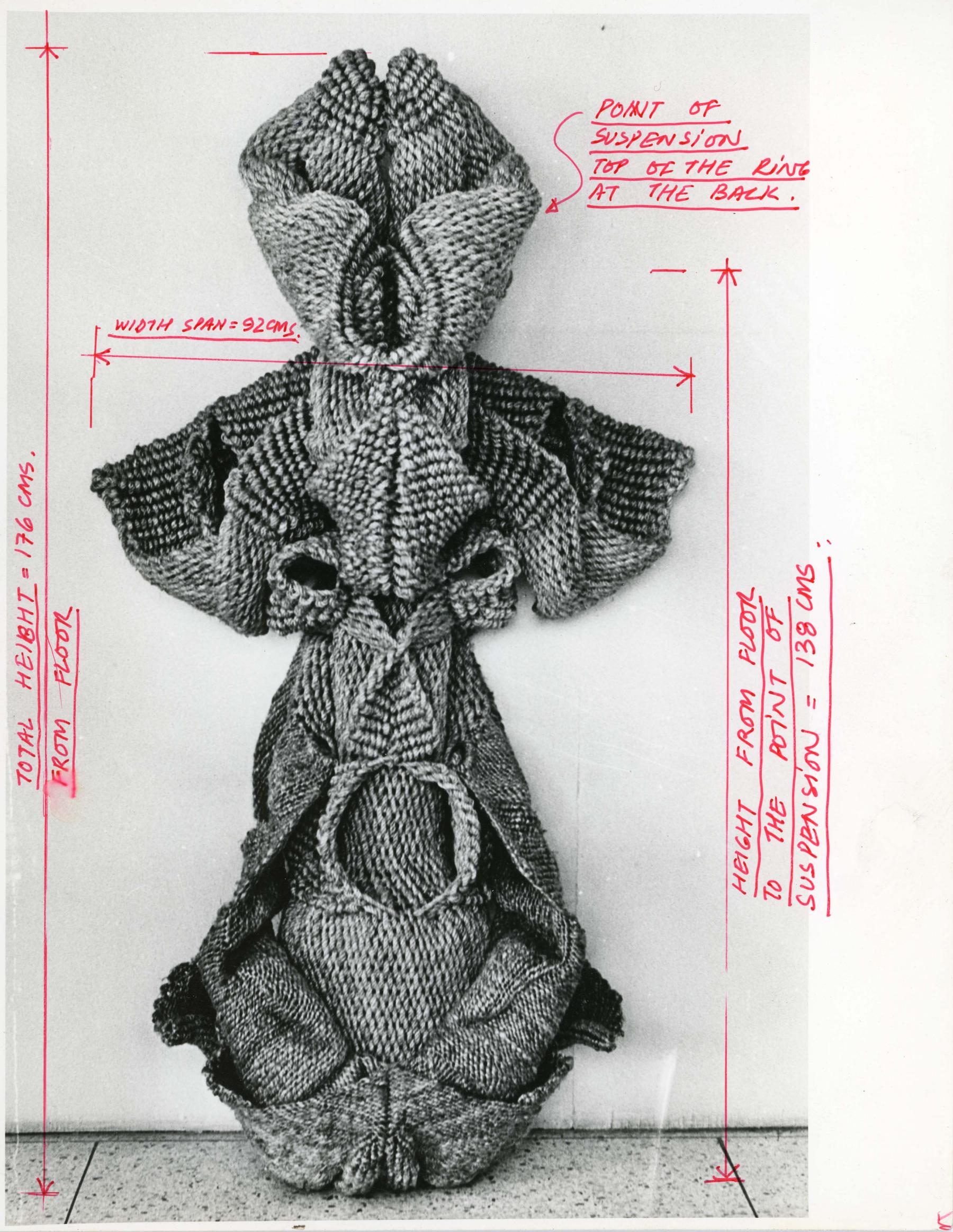

Installation instructions for Apsara, 1985

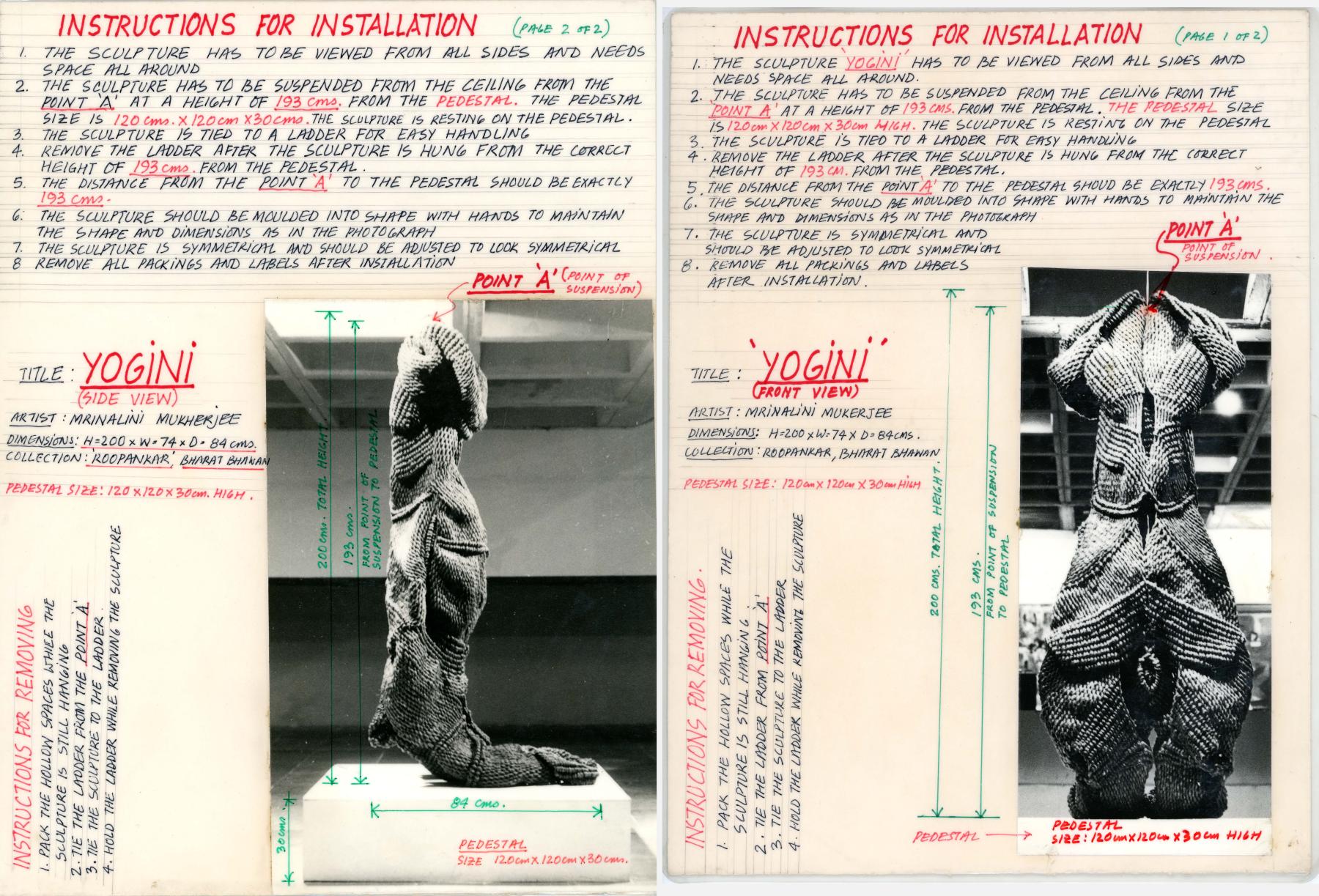

SB: A unique set of materials in Mukherjee’s archive are documents detailing instructions to install her work. These include cut-out photographs of her hemp sculptures, carefully measured and annotated to illustrate their exact dimensions, the point of suspension and height from the floor, and how the work should be unpacked, packed, and cleaned. These were created by her then-husband, Ranjit Singh.

These are particularly interesting in the context of Mukherjee’s description of her working process as “improvised” and additive, working with materials like hemp that “flop about”, while the instructions portray a strong sense of control. How do these inflect the archive for you?

ND: The documents are fascinating; they’re designed in a diagrammatic form by an architect, and seem almost in contrast to her fibre sculptures that are often described as “organic”. These appear to be made around the 1980s, when Mukherjee’s work started traveling abroad and she wasn’t personally able to install them. Also, as you mentioned, the materials are floppy and there is considerable care required to execute the folds as the artist wanted them. When we studied the documents more carefully, we noticed a sense of control on the sculpture beyond the installation—the space around it, the lighting, every centimetre of it mattered. We get a sense that Mukherjee was very particular about aspects such as light when she directed the installation of her sculptures. This presented a tension, in terms of the archive, when these instructions are presented against her own claims of improvisation, as well as the sort of decadent excess that seems to characterise her work and methods. We have heard stories about how Mukherjee would direct installations in her exhibitions, and how particular she was about certain things. This tension became a key prompt for our exhibition, “and it is something which grows in all directions.”

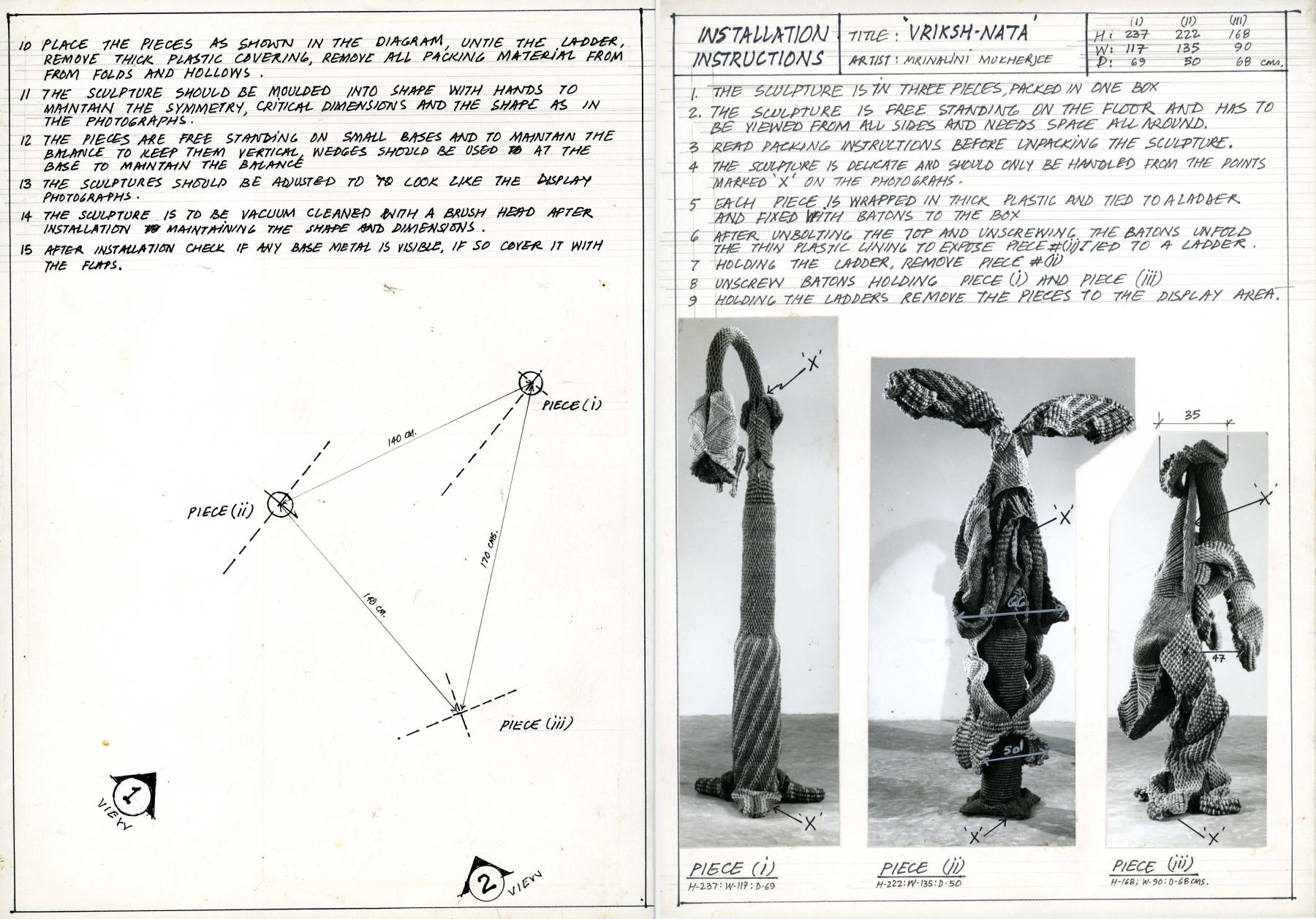

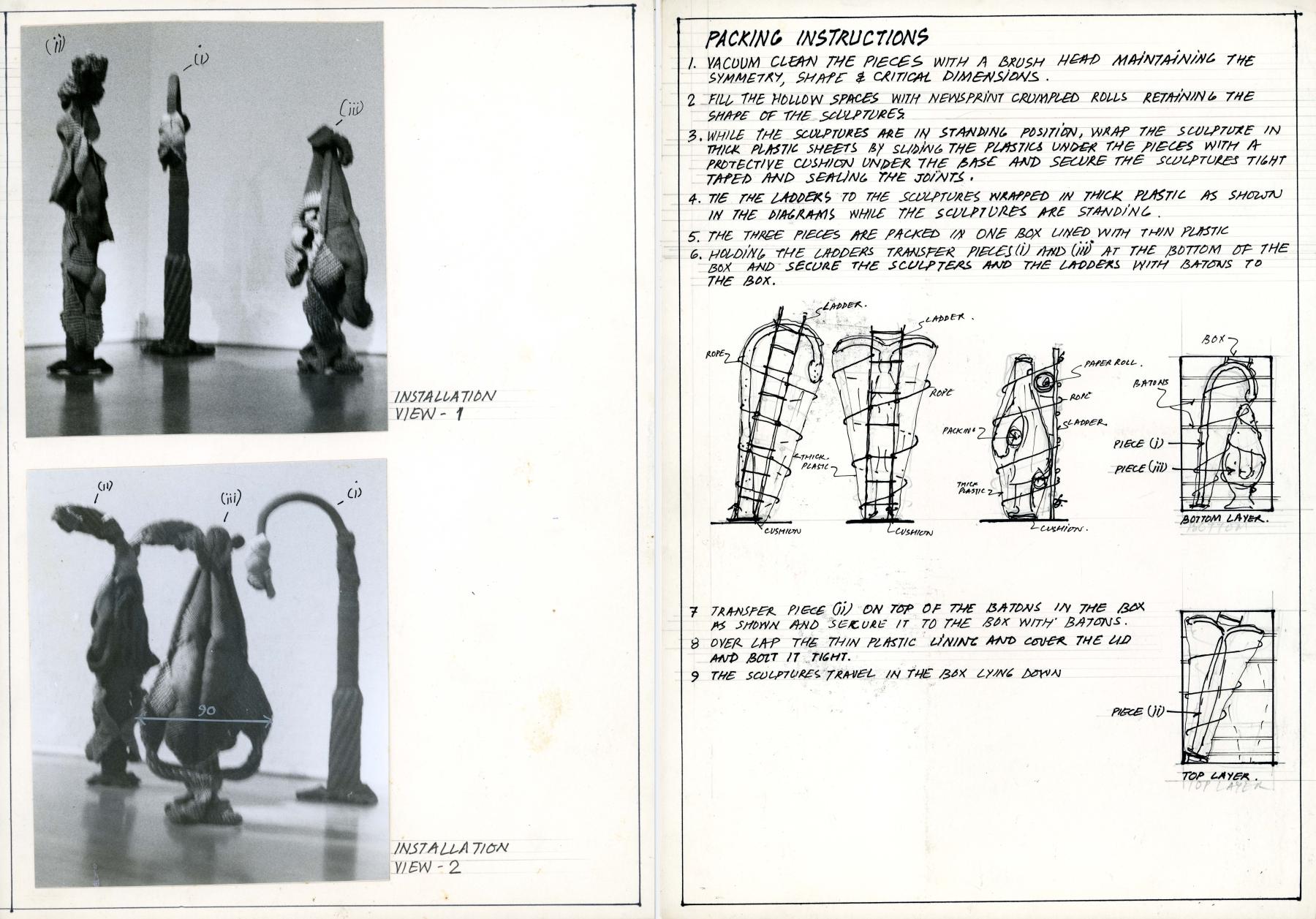

Installation instructions for Vriksha Nata, 1991-1992.

PA: These documents acted as the starting points for us to probe Mukherjee’s process further. If an artist is so precise in the aftermath of her artwork, what must have it been like when she started or as she was making the work? We do not see any measurements apart from these documents—there are no blueprints, drawings or sketches of how Mukherjee envisioned or planned her sculptures. This confounded us because of the sheer scale of the works. It led to a debate amongst the team where we even considered that perhaps some documents were missing. We simply couldn’t figure out how she could arrive at such symmetry and clarity in her work without even a single note. We read a few of her lecture notes carefully, where she talked about improvisation. Mukherjee said that, “I have to start from somewhere, but then I let it grow…” However, in the archive at least, we don’t see how she arrived at the form which is then fixed up so precisely by the centimetre. We began to understand that the measurement was happening at an embodied level.

Installation instructions for Vriksha Nata, 1991-1992.

It is also noteworthy, as you said, that the materials themselves resisted a kind of precision. There’s improvisation “in all directions”, and there’s exact measurements together, in parallel.

ND: I have an anecdote. While Mukherjee’s instructions give us clear measurements, it was very difficult to put together the metadata for her works because each publication has different measurements for the same work—the material itself flops, droops and stretches, changing the length and width. This was something we were cognizant of as we annotated this particular set of materials.

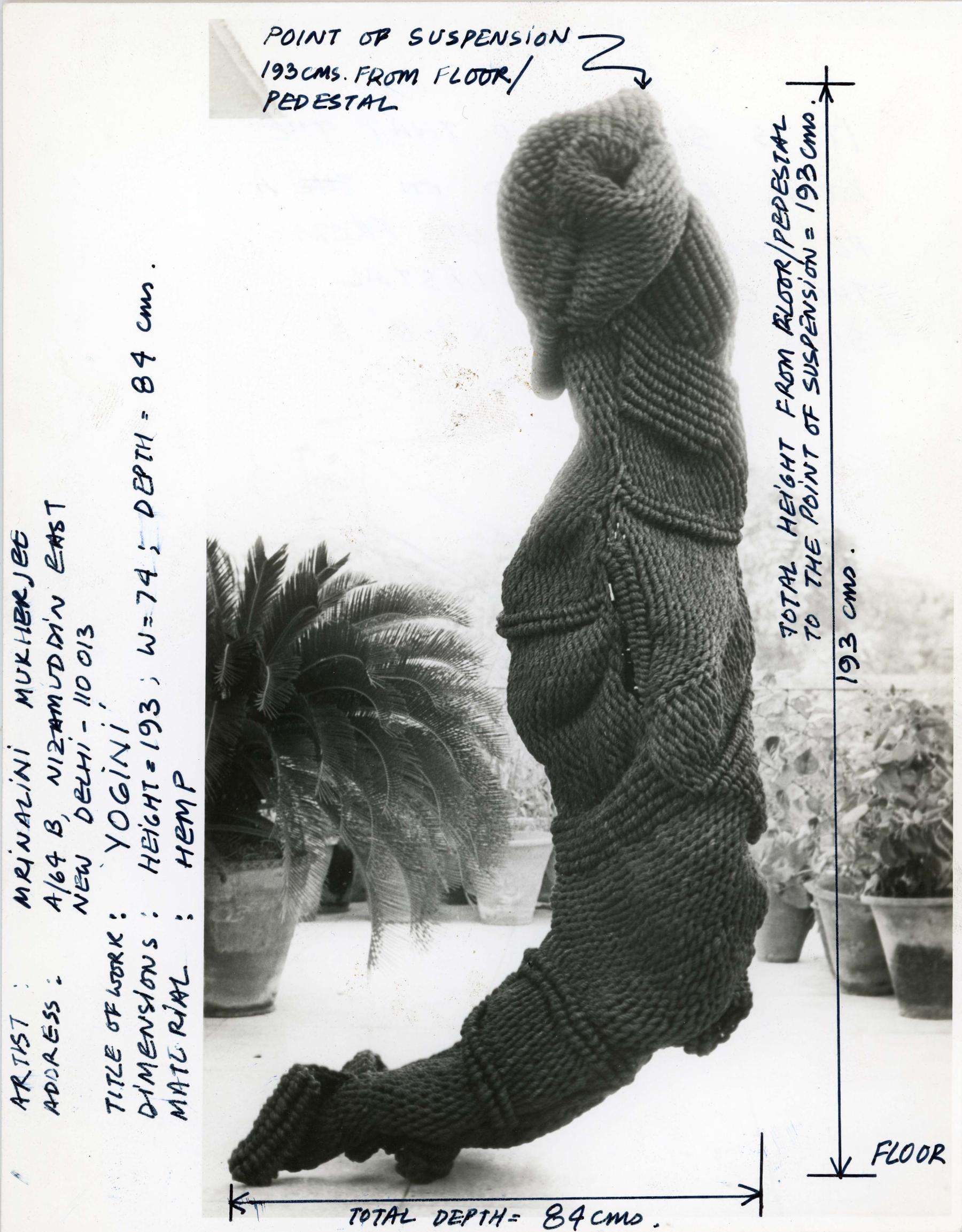

Installation instructions for Yogini, 1986.

SB: The installation instructions led me to three speculations about Mukherjee’s practice and her relationship to photography. The first is that while we may search for blueprints, it seems that photography marked the completion of the work for her.

Secondly, the multiple angles from which she photographs her work also serve as the instruction manuals. It is a purposefully precise rendering of the sculpture because photography, and the chiaroscuro effect it produces helped her highlight every single knot in an otherwise intricate work. Mukherjee wields photography in an essentially documentary way.

The third speculation is that there’s a certain marking of/for posterity in the installation instructions—the artist is clear that photography can be used to ensure that her exact vision for the works carries on. Of course, these documents served a utilitarian purpose, but they take on a different charge in the archive.

ND: Posterity becomes even more interesting to think about because the materials she uses for her fibre sculptures are ephemeral. If you don’t preserve them with great care, they will dissipate. The works are also monumental, and it’s not easy to store or display them. They are susceptible to termite attacks and the like, and even without that, they’re prone to weathering.

Even today, galleries and museums employ these precise instructions for installing her work. We are curious about how art practitioners will respond to these documents as they circulate further.

Installation instructions for Yogini, 1986.

To read the first three parts of the conversation, click here, here and here.

All images from the Mrinalini Mukherjee Archive. Images courtesy of Asia Art Archive and the Mrinalini Mukherjee Foundation.