Furtive Naivete: Seeing Udupi Hotels Like Stig Toft Madsen

In an obscure corner of YouTube lies Stig Toft Madsen’s channel, with its three videos clocking no more than 3000 views cumulatively. In 1991, the year India declared its unambiguous participation in the neoliberal global market economy, Madsen had descended to South India to research Udupi hotels. As an institution with its roots at the end of the colonial era, it has endured well into our times. Shot on a rudimentary camcorder and edited in the now-defunct Reflections Studio in erstwhile Bangalore, the footage is refreshingly amateur. With a rotating cast of cameramen for the three disparate locations—erstwhile Madras, Bangalore and Udupi—the directorial authority fell with Madsen himself.

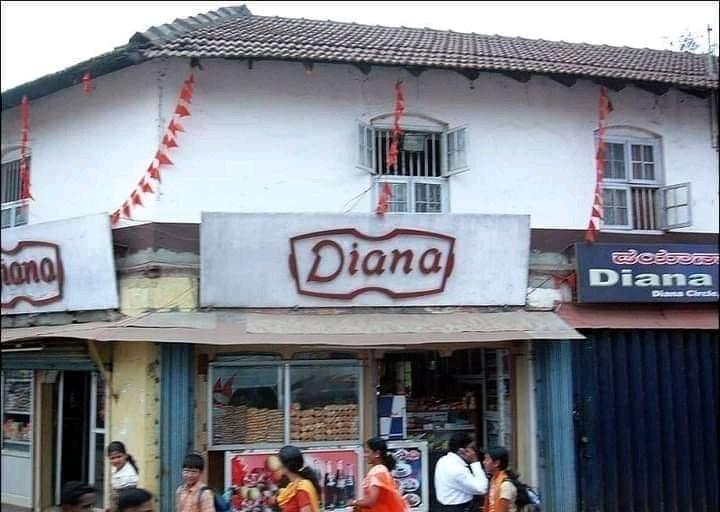

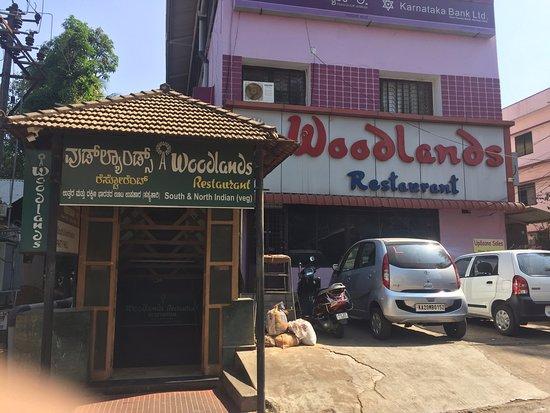

The formula of the videos is a simple one. We see seemingly innocuous interviews with various proprietors of Udupi hotels, genteel historians like S. Muthiah providing their historical insight, as well as copious footage of the exteriors and interiors of the restaurants. The videos display a particularly keen eye towards the labour involved in the daily humdrum of the catering industry—coconut grating, vegetable chopping, the cleaning and upkeep of kitchens, jalebi batter passing through an ingenious coconut shell contraption and the production of what seems like an industrial assembly line of rice.

Madsen’s interviewing style comes off as naive, often pressing on questions that carry little significance. However, it seems like this might just be an exercise in Socratic irony, with interviewees, including the measured Muthiah himself, being excessively self-reflexive and often volunteering odd bits of information. Madsen’s research traces the origin of these enterprises to the resounding snub Brahmins from the Dakshina Kannada region got from the colonial administration as compared to their Tamil Brahmin contemporaries. He writes in a 2012 essay for the collection Curried Cultures: Globalization, Food and South Asia,

“When poverty ‘flushed them out’, as noted scholar and litterateur K. S. Haridasa Bhat expressed it, they had to depend on their main cultural capital, that is, ‘pleasing the mass by feeding rice (anna santarpana or samaradhana)’. The flexibility and management skills built up around the many small and big shrines and temples in Udupi constituted their comparative advantage when they started moving out of their district in the beginning of the twentieth century.”

Madsen also shed light on how Udupi restaurants begrudgingly moved towards modernity:

“In temple rituals, Brahmins have often been served separately with food made in a separate kitchen. The tradition of separate kitchens has not been transferred to the Udupi restaurants, but many Udupi hotels originally had dining areas exclusively for Brahmins… In Madras, activists staged repeated demonstrations against the extension of orthodoxy into restaurants. The Dravidian leader Ramaswami Naicker personally painted over the word Brahmin on a restaurant signboard. In 1938, he incited anti-Hindi riots during which crowds attacked ‘coffee stalls run by Brahmans’. Again, in 1957, a campaign was launched to ‘erase the word Brahmin from hotel name-boards... since such display is irrelevant in a secular state’. Slowly, commensal seclusion and the practice of untouchability have been eroded by commercialization, political activism, and legal reform. The establishments run by Udupi Brahmins played an important part in the expansion of civic space by exposing caste-centered traditions of ritual purity to the forces of change. As a result, seclusion and segregation are now much less frequent.”

This statement is borne out in the amateur videos. In Madras, at the Udupi Sri Krishnavilas on Mount Road, we see officegoers, families, chaperoned women, groups of men in printed shirts and children crowding the restaurant in the morning hours. Likewise, in Bangalore, we catch a large crowd attempting to enter Mavalli Tiffin Rooms in the morning, with some men opting to stand and drink their coffee in the premises while table service carries on efficiently and against all odds. At this stage of the evolution of the Udupi hotel, we also find hoteliers attempting to cater to the upper echelons of Madras society by offering buffets that comprise vegetarian “Western” dishes. With the globalisation of food cultures, the shots Madsen takes of these buffets might strike the modern viewer as absurd, but they mark a time of great rajas in the Indian culinary landscape, where interpid restauranters attempted to arrive at various guesses as to what an au gratin or a stroganoff might be.

Madsen’s meticulously researched work on Udupi hotels can barely be arrived at based on his odd ephemera on YouTube alone. The footage comes off as a wedding video by a rogue cameraman who seems more interested in the filigree than the bride, and yet it is precisely for this reason that they require a bit more attention for the curious.

To learn more about explorations around food cultures, revisit Annalisa Mansukhani’s essay on Reliable Copy’s exhibition at the kitchen table, Anisha Baid’s reflection on Basir Mahmood’s practice and Najrin Islam’s essay on the use of samosa packets in Sofia Karim’s Turbine Bagh.

All images courtesy of Stig Toft Madsen and YouTube.