Sirens of Modernity: Indian Cinema’s Place in the World

A Russian hero and a beautiful Indian heroine clad in fur travel through an idyllic landscape covered in snow, discussing their dream of a shared love. This sumptuously shot film sequence from the Indo-Russian co-production titled Journey Beyond Three Seas/Pardesi (1957) formed the crux of a presentation on 13 May 2023, by Samhita Sunya on her 2022 publication, Sirens of Modernity: World Cinema via Bombay. Covering a period bookended by the Bandung (Asian-African) conference in 1955 and the declaration of Emergency in India in 1975, Sunya’s book is situated at the intersection of transnational media histories and media studies. With a close reading of a set of films and media objects ranging from Hindi film songs to bangles made of celluloid, Sirens of Modernity explores the role of media production in world-making activity.

The cover of Samhita Sunya’s Sirens of Modernity features the singing dancer-actress at the centre of the tome.

Taking the audience through the third chapter of her book, Sunya unpacked this world-making role of media with a detailed reading of Pardesi. The first of a few Indo-Soviet prestige productions, it was shot in colour and on Cinemascope. A true co-production, the film was jointly written and directed by K.A. Abbas and Vasili Pronin and was loosely based on the travelogues of the fifteenth-century Russian traveller Afanasy Nikitin.

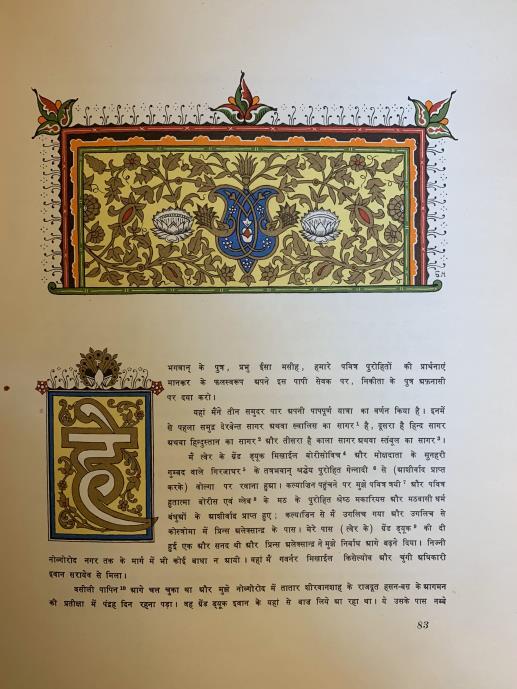

"An Indian noble plays host to Afanasy Nikitin", One of seven Persian-miniature-style card-insert illustrations in a trilingual edition of Afanasy Nikitin's Voyage Beyond the Three Seas (Moscow Geographical Society, 1960), the travelogues Pardesi was based on.

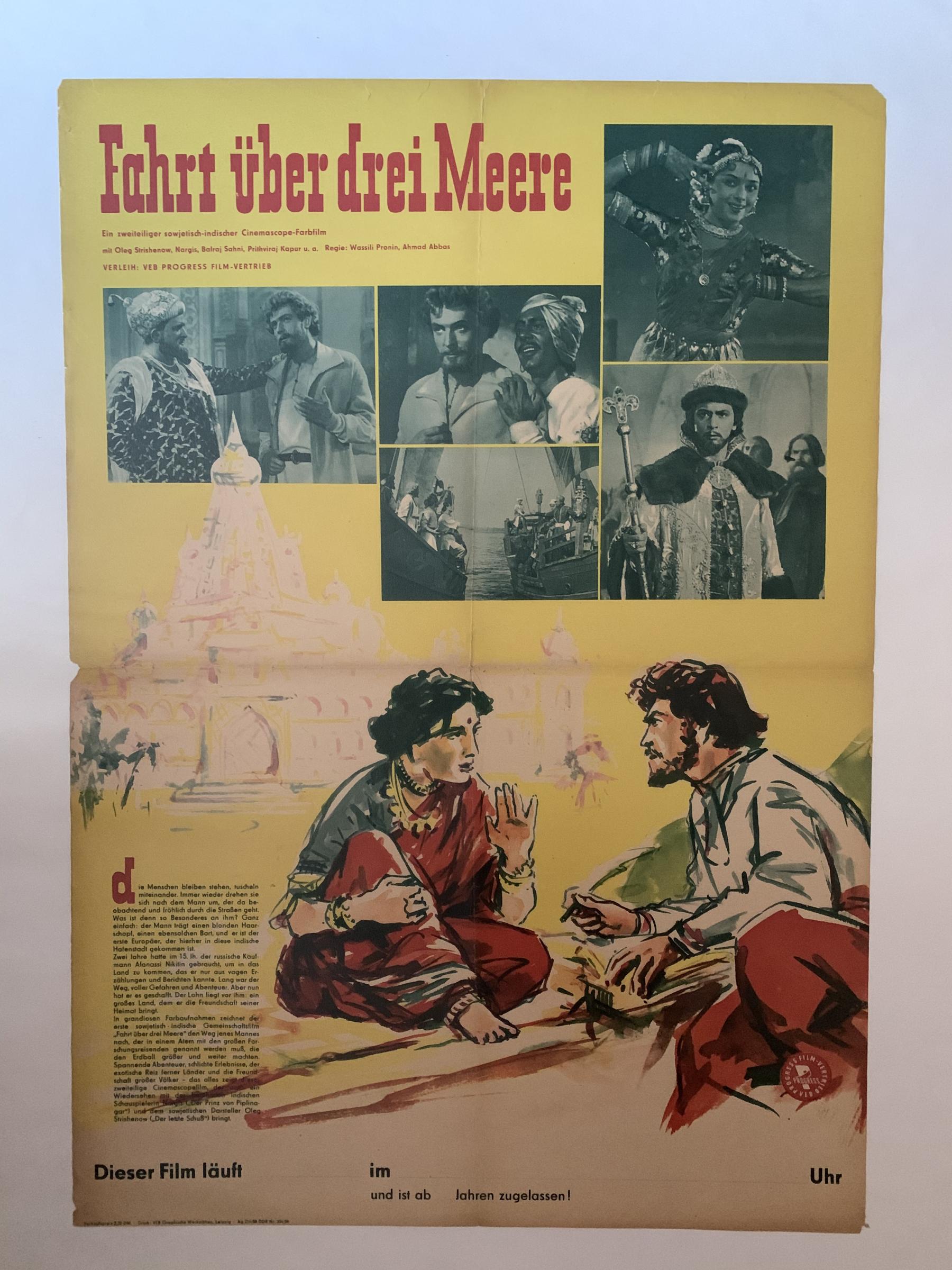

The film was dubbed in both Hindi and Russian, although only a black-and-white copy survives of the Hindi film, which is about four minutes shorter than its Russian counterpart. Pardesi was released in India in 1957 and in the erstwhile USSR in January 1958. A version with English subtitles with the title Journey Beyond Three Seas, premiered in New York in 1960. Although the film featured Nargis in the leading role and was released in the same year as Mother India (1957), Pardesi was not a huge success in India. It did, however, feature music by Anil Biswas, most prominently a song picturised with the dancing star Padmini and sung by Lata Mangeshkar. The film retains much of its appeal today in both its lilting music and the spectacular visualisation, which earned M.R. Achrekar the Filmfare Award for Art Direction in 1958.

East German poster for Khozhdenie Za Tri Morya (1958). The Hindi version of the film was titled Pardesi (1957).

Using films like Pardesi, Sunya draws attention to the historic binary—in both popular and institutional discourses—between the “spectacular excess” of Hindi cinema and the critical acclaim enjoyed by a more “realistic” auteur-driven world cinema. Referencing the varied influence of filmmakers like Abbas, Satyajit Ray, Bimal Roy and Hrishikesh Mukherjee, she carefully unravels how Indian filmmakers from the 1950s to the 1970s were working across formal idioms, languages and industries both within and outside national borders. Ray did not shy away from using elements of melodrama or working with different scales of production and language. In addition, the postwar European discourse of a category of world cinema defined by his films like Pather Panchali (1955), promoted by the rise of international film festivals and the establishment of international film journals, must be read in conjunction with accounts of Bombay films’ overseas reception.

.jpg)

A production still from Subha-O-Sham (1972), one of the films Sunya examines in Sirens of Modernity, featuring Waheeda Rehman and Mohammad Ali Fardin. Image Courtesy of National Film Archive of India.

Sunya chose to focus on what she terms “oddball” films: prestige co-productions, cross-industry productions and some box-office failures. These include, alongside Pardesi, the Indo-Iranian production Subha-O-Sham (1972) and the star-studded comedy Padosan (1968). All of these cinematic texts share a deep reflexivity, a sensitive reckoning with their own status as caught between being artistic and commercial objects. A careful mining of these varied sources reveals that the borders between the purported excess of Hindi-language cinema and a more realist world cinema are more contingent than they seem at first glance.

.jpg)

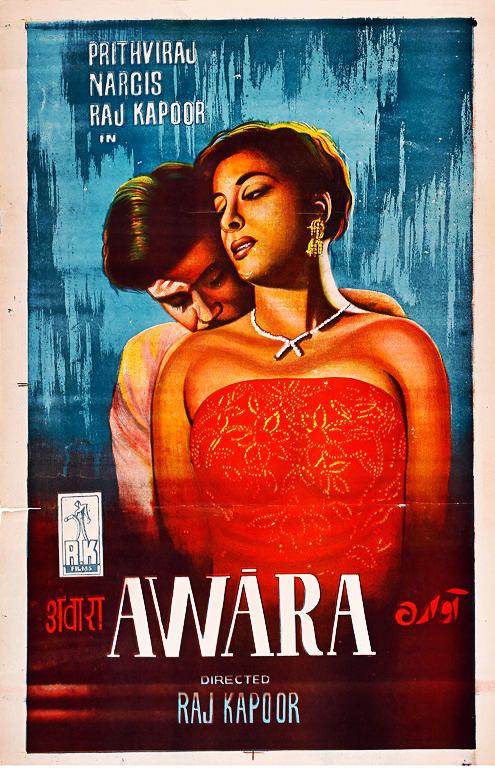

A scene from Awara (1951), with Raj Kapoor and a dog. Some posters for the film were consciously made referencing Chaplin’s famous poster for A Dog’s Life (1918), where the actor was pictured with a stray dog.

The period of the 1960s that Sunya chose to focus on also brings the reader’s attention to what predates Pardesi by a few years—a cinema of and for the people. This was represented through the figure of the tramp, most famously played by Charlie Chaplin and, in India, by Raj Kapoor. While Indian cinema has old and varied connections to international filmmakers and technicians, Raj Kapoor’s Awara (1951) gave it a fresh impetus, garnering an audience across the USSR, China and Central Asia. Abbas, the scriptwriter for the film, was surprised by its success with Russian audiences at a time when Indian filmmakers were drawing on techniques of political filmmaking used in other countries.

A poster for Raj Kapoor's Awara (1951). Courtesy Little Corner.

Raj Kapoor’s acting, the charming young stars of the film, its musical quality and the clear moral structure of the film—with its emphasis on criminality being shaped by societal factors rather than accidents of birth—seemed to hold a universal emotional appeal. Abbas led the first Indian film delegation to the Soviet Union in 1954. Kapoor’s films continued to hold sway over Russian audiences, at least up until the 1964 release of Sangam. As Nargis herself gushed in an interview, “The Russian people had been singing Awara Hun everywhere, even using it as a welcome song when they received us.” On one occasion, an enthusiastic crowd of Russian fans even picked up a car with Kapoor in it and carried it to his hotel.

Looking at films like Awara opens a time when Hindi-language cinema in India participated in mobilising collective imaginations and practices aimed at material transformations in the world through what Abbas termed “romance, comedy, and somewhat jazzy music.” Scholars like Masha Salazkina examined these histories in their documentation of events like the First Tashkent Festival of African and Asian Cinema in 1968. The popularity of Kapoor’s films in the erstwhile USSR and Turkey, his participation in the festival, the vivid emotional response of a global audience to Hindi cinema—all of these point to a cinematic field that spurred the evolution of shared cinematic languages at the intersection of geopolitics that has largely been put aside when situating the global histories of Indian cinema.

To read more about scholarly interventions with reference to popular Bombay cinema, revisit Ketaki Varma’s essays on Ranjani Mazumdar’s reading of film posters as art objects, Sabeena Gadihoke’s exploration of stardom through soap advertisements and Debashree Mukherjee’s account of the transition from silent cinema to the talkies.