Through the Looking Glass: Pardesi and the Radical Power of Love

Examining films like Pardesi (1957), Padosan (1968) and Subha-O-Sham (1972), among others, Samhita Sunya’s Sirens of Modernity (2022) deftly draws our attention away from solely national histories of cinema. Through these productions, whether by their nature as international co-productions or as films that gained an international audience, she closely reads the structures of public circulation and sociability in the interaction between Indian and world cinema from the 1950s to the 1970s.

Afanasy's ship reaches India.

Sirens of Modernity stands apart from other texts in that it does not limit its scholarship to detailing the genesis of this shared sociability and international(ist) imagination. Even as Sunya locates the films she selects within the volatility of the period—one of optimism in India’s role as global peacekeeper—she sharply critiques their homosocial nature. For instance, in Pardesi, love and desire erupt through the narrative, where idealised male bonds of friendship and fraternity with a tinge of Gandhian austerity are privileged. Women remain confined to nurturing, compassionate roles, while men participate in heroic masculinity defined by values of work, duty and friendship. In Sunya’s reading, the figure of the singing dancer-actress metonymically embodies the very excess of Hindi commercial cinema—whether its excessive commercialisation, audiovisual excess, or libidinal excess—as seductive cinema appealing to vast audiences. Throughout the book, the idea of excess and its painstaking deconstruction through the figure of the singing dancer-actress becomes an organising principle. Sunya brings an affective charge to her understanding of geopolitics through cinema, moving out of the confines not only of state-centric grand narratives but also beyond the rigid boundaries of a rational-critical mode of study.

Wide shots of fisherman, among other vistas upon Afanasy's arrival in India. Men in the film are consistently shown at work, whether fishing or tilling the fields.

In a podcast hosted by the author Aswin Punathambekar, Sunya casts further light on this when she discusses her love for Indian films and their songs. She fondly recalls how these songs took on the role of social currency, both with other diasporic populations and with her own cousins in India. Hindi film music is an undeniable force that elicits strong emotions from the public; the impassioned space it creates forms the basis of Sunya’s exploration of the historical and ethical stakes of cinema in India. Guided by her own love for the form, Sunya hits upon the crux of the matter—that Hindi cinema provides pleasure to a spectator who is willingly seduced by its very excess.

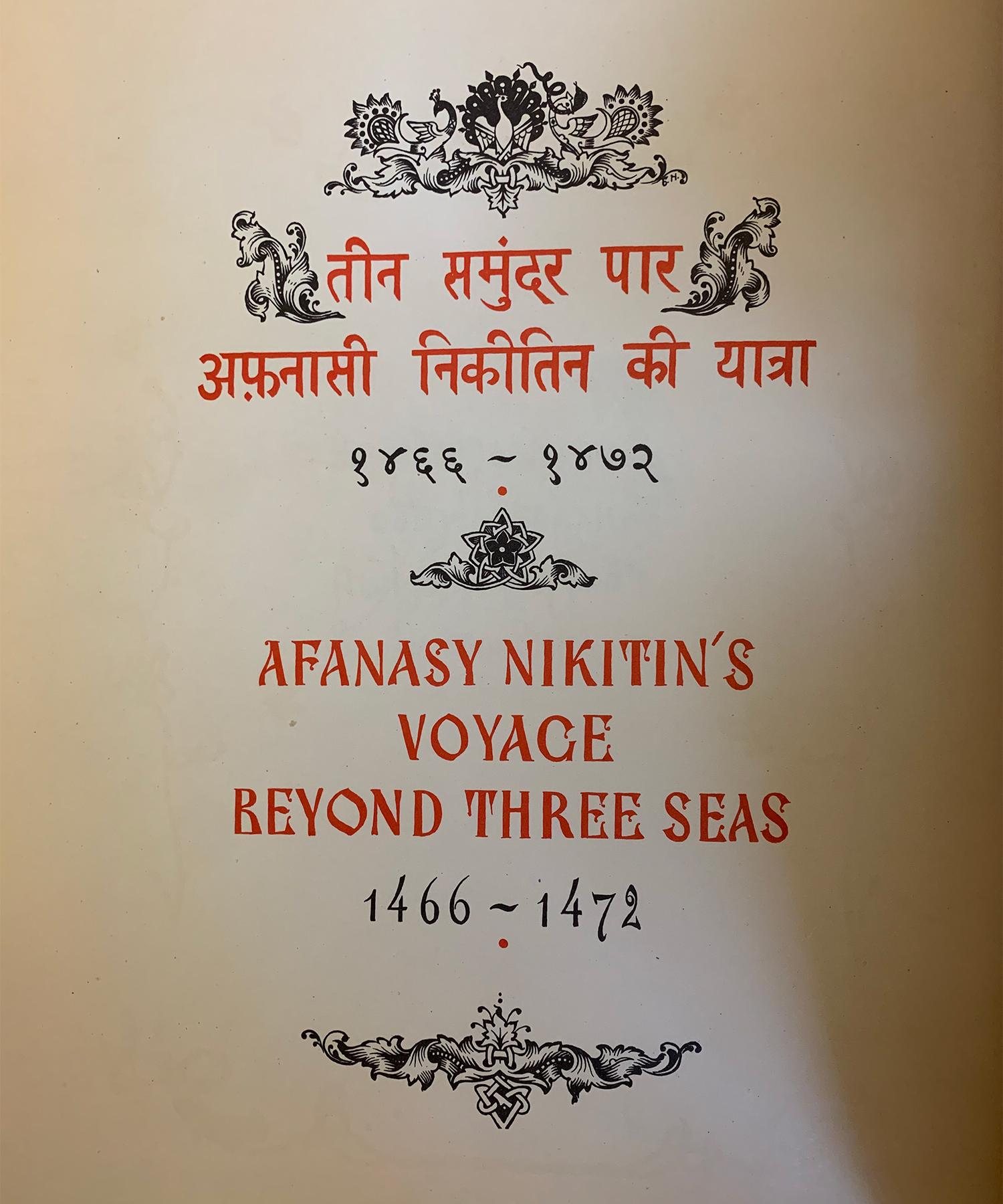

Hindi and English title page of a trilingual edition of Afanasy Nikitini's Voyage Beyond the Three Seas (Moscow Geographical Society, 1960). This was the travelogue Pardesi (1957) was based on.

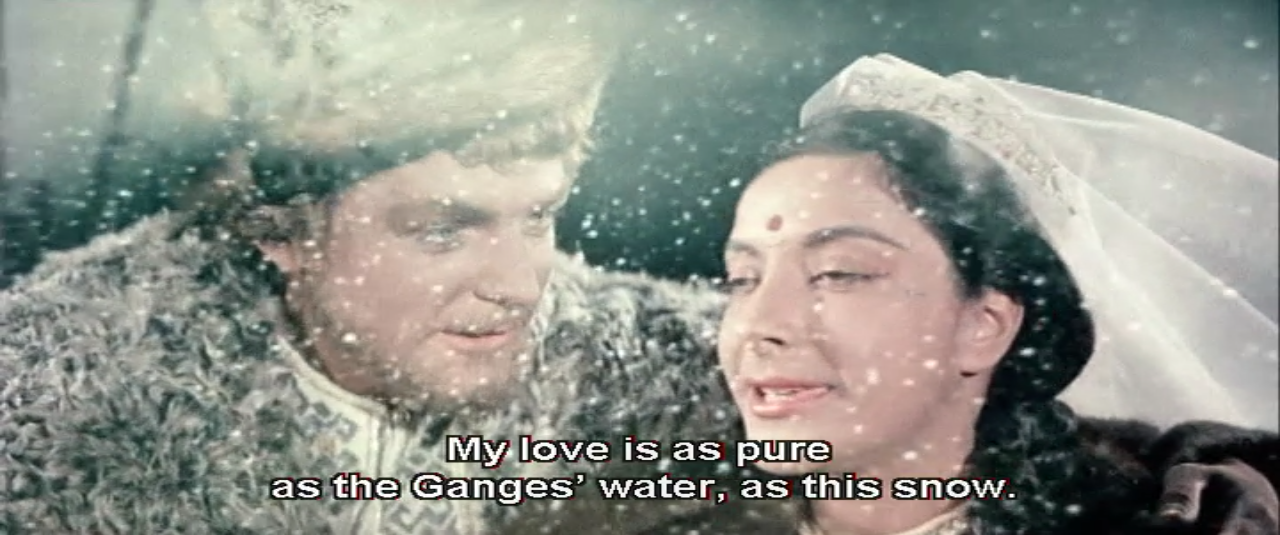

This unique agency afforded to the film spectator ties into the libidinal excess of the actress and the ideas of love and desire. Reading the narrative of Pardesi against the grain, Sunya focused on the dream sequence from the film in her discussion. In the sequence, Afanasy Nikitin (Oleg Strizhenov) dreams of being reunited with his beloved Champa (Nargis) in a snow-covered Russia. His dream is shattered when he realises that their worlds are too far apart, and he screams out, “Why is the world organised this way?” Taking this exclamation as a point of departure, Sunya’s work takes the reader on an exciting exploration of the idea of love as a radical challenge to the systems of world-making that come into being through these films. Love—whether between the hero and heroine or the cinephile’s engagement with Hindi films and their music—disturbs the set structures of the world, becoming a point of study where the dangerous replication of gendered roles is thrown into flux.

Afanasy's romantic reverie.

Sirens of Modernity also explores cinephilia through small stories, anecdotes and varied objects like bangles made of celluloid, bringing to light sensory histories that are rarely studied. Illuminating the trafficking of cinema both as text and as material, she reminds her reader that sending a film reel to the chudikhana (bangle-makers) was a sign of failure for a film. A common trope in film history, it clearly illustrates the equation of a “bad” film with the liminal position of feminine accessories.

Sunya is equally creative in her methodology and the sources she chooses for her research. In her conversation with Punathambekar, she recounts going to the National Film Archive of India and numerous US-based libraries to browse their robust periodical collections. She also visited VCD markets in Mumbai to source copies of the films and audio cassettes, apart from searching for user-uploaded segments of songs on YouTube. Sirens of Modernity opens up film scholarship, bringing alive the material and textual history of Indian cinema by locating it within an international context. It also invites a collaborative scholarship to spring from further explorations in this vein. This is a timely intervention given that the state’s attitude towards excess has changed radically since the 1950s, as evidenced by the success of films like RRR and the Indian government’s pride in the same. Sirens of Modernity and its author urge both the student and the lover of film to take stock of the ethical and deeply gendered stakes of the medium.

To read more about scholarly interventions with reference to popular Bombay cinema, revisit Ketaki Varma’s essays on Ranjani Mazumdar’s reading of film posters as art objects, Sabeena Gadihoke’s exploration of stardom through soap advertisements and Debashree Mukherjee’s account of the transition from silent cinema to the talkies.

All images are stills from Khozhdenie Za Tri Morya (1958), the Russian adaptation of Pardesi (1957) co-directed by Vasili Pronin and K.A. Abbas. Images courtesy of Samhita Sunya.