The Exemplary Intellectual: On Akshay Indikar’s Udaharanarth Nemade

Akshay Indikar’s documentary Udaharanarth Nemade (For Example, Nemade, 2016) mixes fiction, reportage and interviews to present a largely adulatory portrait of the Jnanpith Award-winning Marathi writer and critic, Bhalchandra Nemade. A graduate of English literature, Nemade taught the discipline in several colleges across Maharashtra and Goa. Considered a difficult intellectual figure in modern Indian literature, he has been dismissed derisively by Indian English writers for his notorious defense of desivaad or nativism. Nemade often railed against the oppressive and deadening influence of English as a colonial language that continues to prey on indigenous languages, myths and cultures. This has often led to facile debates on “authenticity” from both sides, as they tend to delve into a stark binary. Nemade is portrayed as a staunch traditionalist, if not a “nationalist” or even a “xenophobe”, who insists upon “the mirage of the organic community that so haunts our vernacular writers.” On the other hand, it is implied that English-language writers are easier cosmopolitans and tragic handwringers in the face of demands made by “vernacular” readers and writers.

It is difficult to dismiss the safety of this binary—it seems to support the idea, quite naturally, that nationalism originates in the provincial back-alleys of the nation and the bonds imposed by such a petty set of exclusive demands can only be cast off by a deliberate embrace of a “global” language like English. Indikar’s portrait of the writer puts his ideological positions in a heady tumble-dry, as it mocks the expectations of those who would wish to categorise Nemade as either hateful or heroic.

Indikar, a graduate of Pune’s Film and Television Institute of India, advocates a cultural homogeneity similar to Nemade’s. During an interview, he reportedly expressed,

“For me, the primary function of cinema is to showcase our lives, our realities and our peculiar reactions to them. I could not find cinema that expressed this in my mother tongue—Marathi. After having watched films from different cultures made in different styles and at different periods, I began getting a sense of the kind of cinema I wanted to make. I do not consider Marathi as being a stepping stone to Hindi or English; I believe I can reach out to people with films made in Marathi.”

While this harmony with Nemade’s worldview allows Indikar to get away with his adulation, the filmmaker does not only express reverence. Yet the critique offered is not enough to assuage the conscience of English and other language-speaking viewers from other parts of India (or the world) to believe that they have been presented with an “objective” view of an important writer. Perhaps a way of suggesting the precise approach would be a sort of writerly engagement, where Nemade is credited as a fiercely original voice, producing meaning through his work instead of passing along a tradition without commentary.

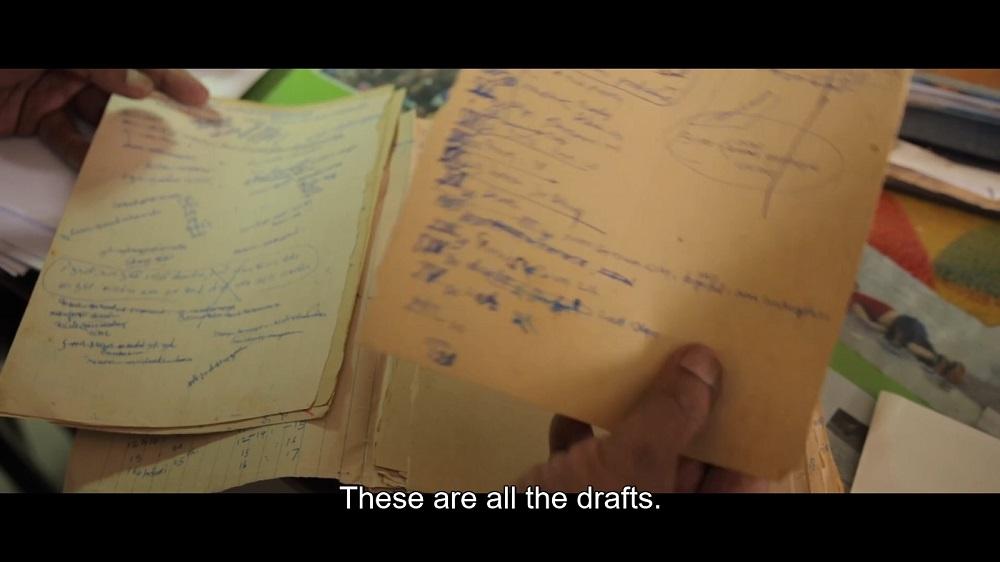

One might expect a traditionalist writer to wallow in the nostalgia of a greatness gone by, but Nemade holds no such illusions. His ideas are shaped by landscape, people and history instead of abstractions about the past or myths of greatness. He is neither a chauvinist of the regionalism popularised in and around Maharashtra since the advent of Bal Thackeray in the 1960s nor an apologist for Hindu nationalism. The documentary was made after the publication of the first couple of volumes of Nemade’s magnum opus, Hindu. The book attempts to recover the everyday, folk lives of the unbounded religious system—seen through a vast, civilisational narrative beginning with the Indus Valley Civilisation—that was consolidated in the modern period as Hinduism. The author remembers the syncretic cultures that have shaped his taste in literature while he was growing up in a village in northern Maharasthra. These ranged from European classics translated into Marathi by a frequently jailed Gandhian called Sane Guruji, to Bhakti poets and narratives drawn from Sufi literature and the Quran. “Later, I found that this was not simply rural or isolated—but part of world literature, as it were,” Nemade declared.

Nemade does not reject the world—as his critics would contend—instead he forcefully denies the authority of the economic system imposed by globalisation through a critique of its natural legitimacy. In the film, Nemade explains how local economies are affected by commercial demands made upon their crops and soil, distorting their natural proclivities. He insists that the world must be met through more acceptable methods, such as translation and the intellectual persuasion of ideas that can help one appreciate their own landscape.

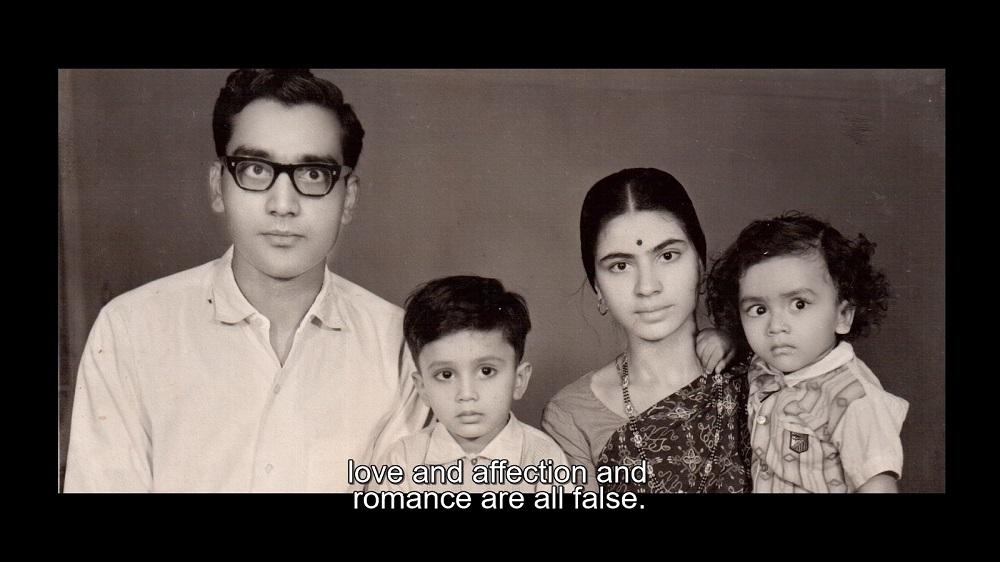

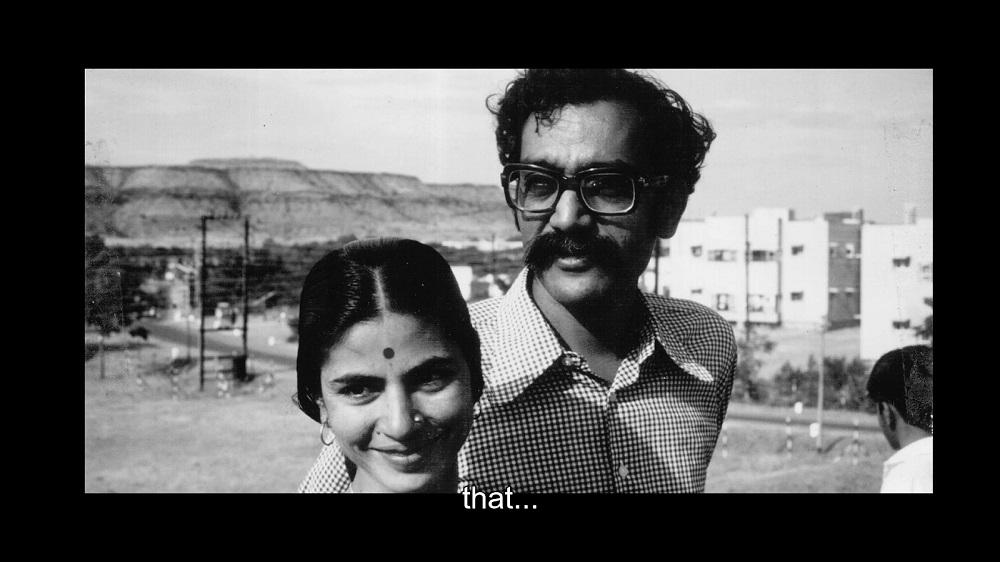

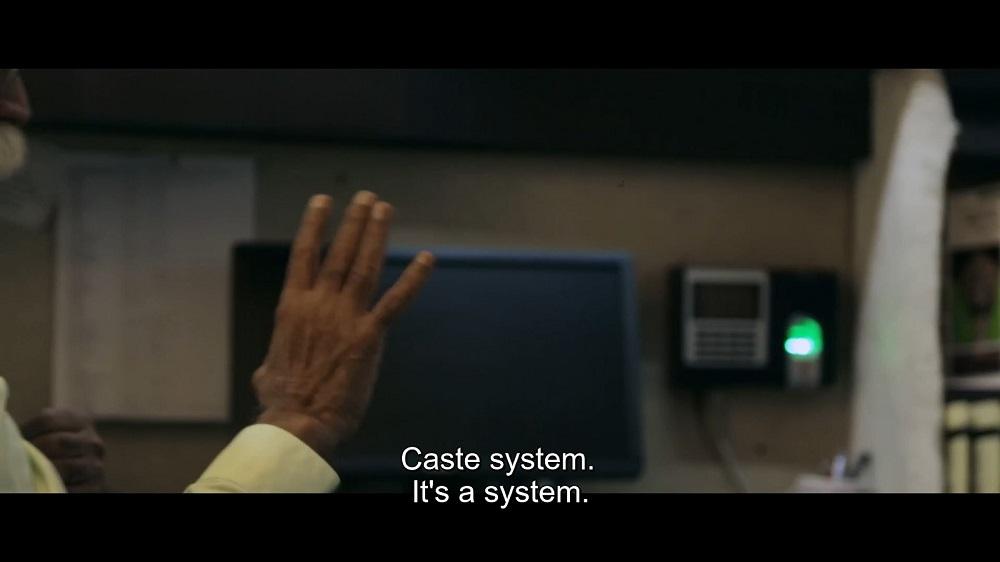

Several haunting questions remain—for instance, Nemade’s wildly dismissive attitude towards companionate marriage. He sees marriage as a way of solving a home economic problem by dividing labour sexually, which is hardly an original idea. He also has a hackneyed view on the ill-effects of reservation in education and government employment (even as he believes in constitutionally-mandated radical equality among people across all castes). However, the film challenges the viewer to engage with Nemade, to draw close to the wellspring of these positions as they gain power in different forms across the country today and find ways of tracing them to the popular but cracked voice of the nation that often originates from its various regions.

To read more about documentary films that present moving portraits of individuals, visit Ankan Kazi’s essay on Kausik Mukhopadhyay’s practice as represented in Avijit Mukul Kishore’s Squeeze Lime in Your Eye, Arushi Vats’ piece on Pelin Esme’s The Collector and Sukanya Deb’s reflection on Mochu’s reading of K. Ramanujam.

All images from Udaharanarth Nemade (2016) by Akshay Indikar. Images courtesy of the artist.