Cinematic Cartographies: Anuj Malhotra on The Flaherty Seminar

In the second part of our conversation with Anuj Malhotra about The Flaherty Seminar, we explore the relationship of the seminar with the cultural landscape of Bengaluru and the larger ecology of experimental filmmaking in India.

The gaze oscillates between the subjective and the objective in If from Every Tongue it Drips (Sharlene Bamboat, 2021).

Kshiraja (K): How do you think the seminar fits into Bengaluru’s existing relationship with queer cinema?

Anuj Malhotra (AM): Siddarth Ganesh, who helps operate the Queer Archive for Memory, Reflection and Activism (QAMRA) at the National Law School of India University (NLSIU), told me about Bengaluru’s long history of engagement with queer films. This includes training filmmakers on the margins of conventional identities to take up cameras and begin telling their own stories. It is not something I knew when we decided to host the seminar pod in Bengaluru. While this is obviously very exciting, it also finds many precedents within the history of Indian film. There has always been a desire to transfer these means of production to people on the peripheries so that they can make their own films and participate in processes of media creation.

Another attendee pointed out how there is a whole network of queer groups across the city who could perhaps not attend this event because it was in a semi-posh locality and, therefore, inaccessible to them. But Oorkathe is also a queer-friendly space, so there is an argument to be made for that as well. It is such an interesting paradox of cultural organisation because you want to go to newer places, expand that network and establish new nodes, but that also means that you end up alienating certain audiences. It becomes a double-edged sword.

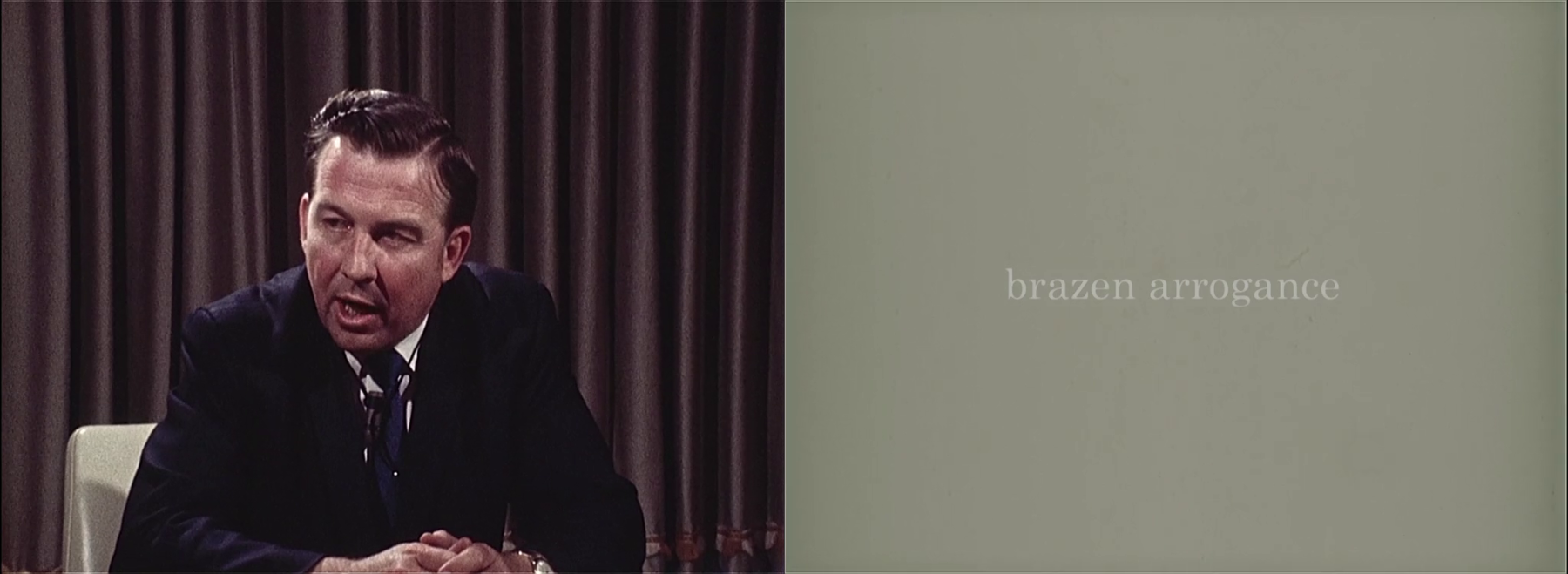

Angelo Madsen Minax maps lessons for the future against cold-war era footage in Stay with Me, the World Is a Devastating Place (2021).

K: Which films in the line-up stood out for you in terms of how the audience in Bengaluru engaged with them?

AM: Loads (1980), by Curt McDowell, is one such film that stood out. It is an experimental short that reverses the male gaze and declares cinema’s voyeuristic glance. The film presents a nuanced depiction of objectification in cinema. The camera, which is seeking a certain body, then also becomes equated with the filmmaker himself, as there is a conflation between the body of the camera and the filmmaker. Then, there is the metaphorical joke—the roll placed inside the camera is, in effect, “loaded” into it; therefore, to make an analogue film is to “shoot a load.” Fluctuating between pleasure and desire, the filmmaker’s gaze is still mediated by his lens. He enters the frame and begins to exercise or indulge in his desires in order to arrive at pleasure. I think that the central thesis of the film is very interesting, but certain elongated graphic scenes caused some discomfort, frustration and resistance from the audience. Surprisingly, it was the film that yielded the most conversation on the first day. I think it made people aware of themselves in a way. This may be the highest purpose of art, but I do not want to sound too romantic about it.

Another film that comes to mind was screened on the third day, called If From Every Tongue it Drips (2021) by Sharlene Bamboat. The filmmaker deploys a fluctuating subjective glance on the city of Karachi, as her car merely drives on the road while she describes everything that she sees, in a way captioning it. But the aspect of attention and how the form of the film is able to divide it is very interestingly achieved. Given that the filmmaker is describing a certain object within the frame, audience members begin to look elsewhere or for something else that catches their attention in the frame.

Loads (Curt McDowell, 1980) sparked conversations at the Bengaluru pod.

K: With a cultural institution like the Flaherty beginning to create a physical presence in India, what do you think it might mean for non-fiction, experimental or avant-garde filmmaking in the country?

AM: I am not sure, I think it is too early to have an impact. I think it falls upon us—if we do have future editions—to activate and catalyse a network of peripheral filmmakers and filmmaking traditions and include them within the folds of the audiences for the seminar. It is only when there is some sort of confluence of the seminar’s programming with their filmmaking practice that a catalysis can happen and the seminar can begin to inform experimental filmmaking and its larger ecology in India.

But, at the same time, we have been working towards ways of including India within the larger network of conversations in global cinephilia, to see how we engage and interact with its currents. This is not so that we are influenced by it, which is a burden that we have already had for so many years. Rather, I believe it can be the means by which we differentiate ourselves and arrive at our own sovereign local models through which to engage with cinema. I think that can be achieved only if we engage with the larger traditions and discourses from around the world. Ultimately, I think—and this is from my experience as a film society activist—we have not really arrived at a local idiom or vocabulary for talking about films. Our discourse or conversations still depend very much on influences from the West or from the coloniser. I think that it is an ongoing process and perhaps The Flaherty Seminar features as one of the steps in that process.

Bengaluru's engagement with queer cinema forms a backdrop for the ecology of film in the city. Image courtesy of Sumeet Kaur.

In case you missed the first part of this conversation, read it here.

To read more about Anuj Malhotra’s practice, revisit his conversation with Najrin Islam about the Garga Archives.

To read more about forms of queer reflection in India, read Avrati Bhatnagar’s essay on William Gedney’s photography practice and Annalisa Mansukhani’s engagement with Tejal Shah’s video art.

All images courtesy of the artist/The Flaherty Seminar unless specified otherwise.