From the Rural Archive: Peasants, Caste and Communalism

The early twentieth century witnessed an overwhelming production of letters, petitions and newspapers across the rural hinterlands in north India. A survey of this print culture challenges the conventional understanding of the agrarian world by offering more than just statistics on economic yield, land holdings and economistic policies. The private papers of the peasant leader Charan Singh (1947–87) and the Muzaffarnagar Zamindar Association (1920–45) are used here to trace the strategies adopted by the landowning class that ranged from posing as peasants in late colonial and postcolonial India to adhering to far-right politics from the 1990s. Moreover, the period following the demolition of the Babri Masjid on 6 December 1992 allowed proponents of peasant rights to reinvent themselves as gatekeepers of majoritarianism.

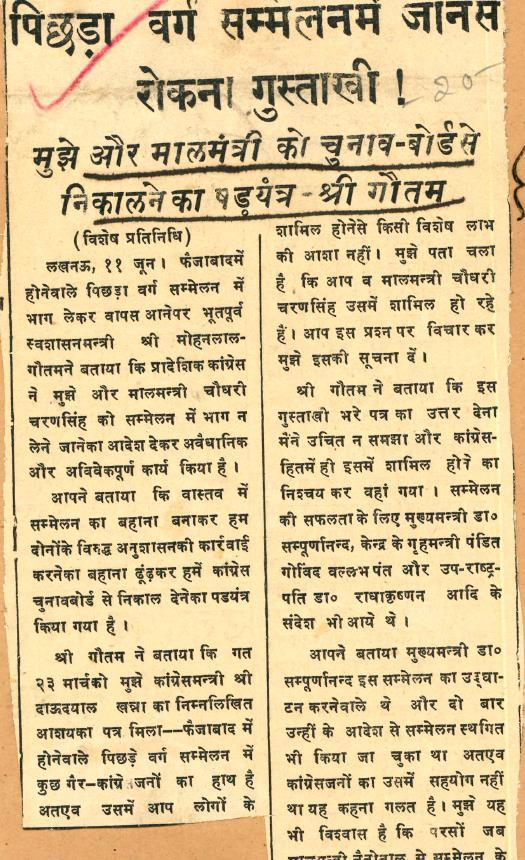

Newspaper report on attempts by the Congress leadership in UP to prevent Charan Singh and associates from attending the Backward Class meeting in Faizabad. (1956. Source: Charan Singh Papers, Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

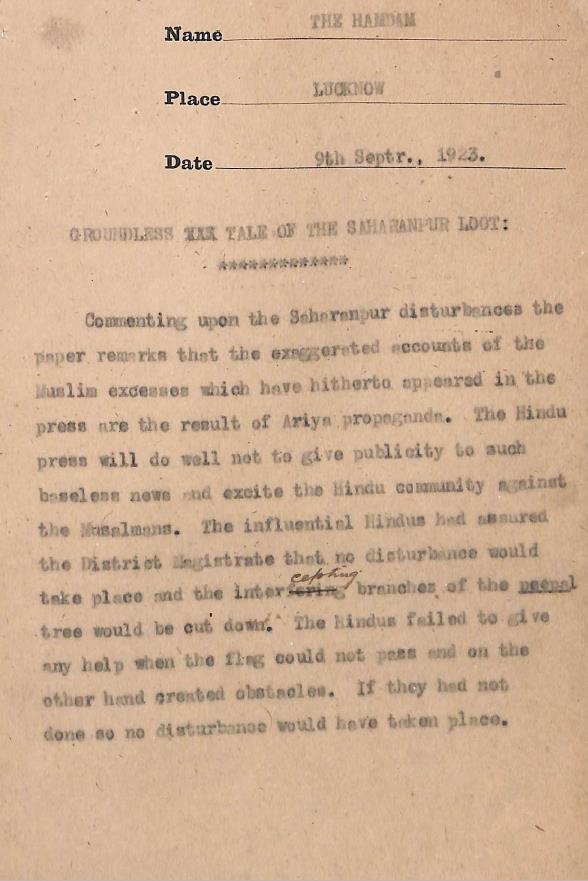

Soon after independence, Charan Singh, a staunch Gandhian and popular Jat leader from Uttar Pradesh emerged as an important peasant leader in 1950. With ties to the Congress Party, he would go on to serve brief stints as the state’s Chief Minister as well as the Prime Minister of India. A depleted national granary had led the state to inaugurate a policy of agrarian revivalism, and the peasantry was offered concessions which went on to fill the coffers of the freshly minted peasant castes. Responding to the issues of rural backwardness, Singh anchored his politics within a coalition of dominant agrarian castes. These caste alliances were part of older associations that were made stronger due to the birth of the Hindu far-right movement in colonial India. Landholders exercised immense clout during communal skirmishes, especially at the time of investigation into an incident of violence. The following report in the Hamdam shows how the Muslims of Saharanpur were wrongly persecuted after a communal incident due to the influence of Arya Samaj propaganda.

Extract from Crime Investigation Report showing media reportage on Saharanpur disturbances. (1923. Source: CID records- Uttar Pradesh State Archives, Lucknow.)

In an Urdu news article from 1947 titled “Another dictatorial statement by Choudhary Charan Singh”, the leader was quoted as sending out a stern warning to the Indian Muslim League for playing a role in the partition of India. Singh further warned that Muslims in India would be held responsible for any harm that was caused to Hindus and Sikhs living in Pakistan. Singh was of the view that if Pakistan could not shoulder the responsibility of minorities, then India too should not be forced to bear the burden of Muslims.

Newspapers Samrat and Hindustan cover Charan Singh’s vitriolic threat to the Muslim League. (1947. Source: Charan Singh Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

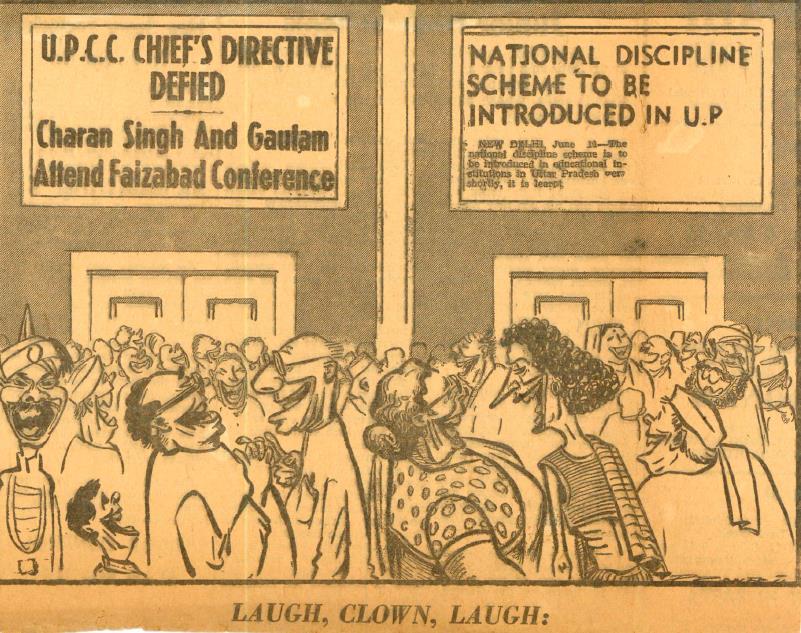

However, Singh’s communal overtones were not of concern to the Congress since the party felt uneasy about his growing popularity as a Backward Class leader in the north. The party frequently censured Singh either in print or through party directives.

Cartoons depict the growing schism between Charan Singh and the Congress. (Source: Charan Singh Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

Cover of the Royal Commission on Agriculture in India Report. (1928. Source: Archive.org.)

The strongly communal character of Backward Class politics has a longer history that is tied to colonial experiments with land and cattle. The early twentieth century witnessed a series of conferences and commissions that responded to the Empire’s exigencies over cattle and grain productivity. The Royal Commission on Agriculture accommodated members from landholder associations who were chosen as first respondents on matters concerning agrarian stakeholders (rentiers, graziers and occupational castes). These contestations and negotiations form the quotidian life in the hinterlands and come alive in the multiple literary sources that continue to await recognition as representing an agrarian archive.

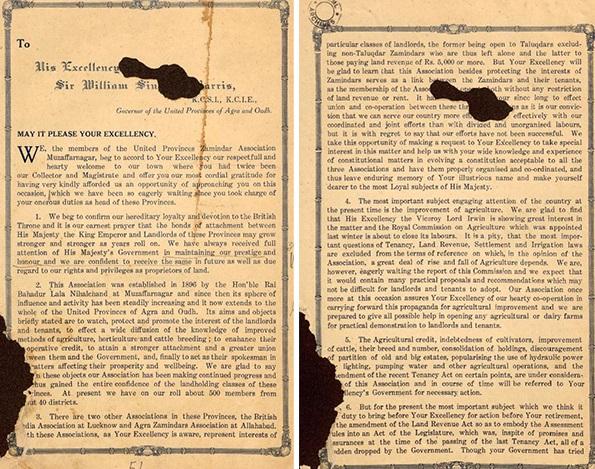

Landholders used their formal associations to demand greater control over their tenants and also determine terms of land use and occupancy. For instance, in the debates over the Rent Act of 1901, landholders petitioned the government to deny rentiers from claiming privileged hereditary occupancy rights. The image below shows a long-drawn-out petition made to the government by the Muzaffarnagar Zamindar Association demanding concessions in revenue payments as well as discretion over rent-paying tenants.

Petition by the Muzaffarnagar Zamindar Association to the Governor of UP. (Source: Muzaffarnagar Zamindar Association Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

The government often gave in to such demands in order to soften the blow of the unpredictability that landowners faced due to land settlements and revenue expectations. The British Empire in India was also attentive to the perils of losing the landowners in the face of popular resistance posed by movements centred on caste, peasants and nationalism.

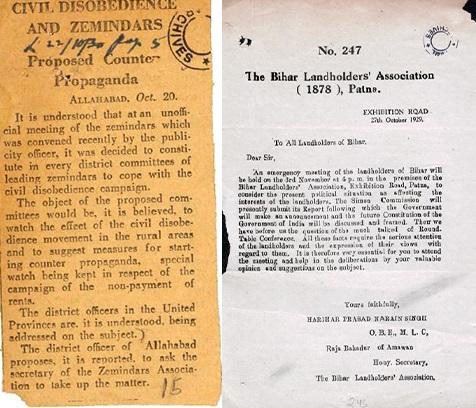

Landholder associations express grievance towards the Civil Disobedience movement and allege unfair representation in the round table conferences in London. (1929. Source: Muzaffarnagar Zamindar Association Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

Gandhi’s Civil Disobedience movement in the 1930s included the quit rent campaign that forced landowners to respond to the rising surge of peasant movements being led by the Congress and Communist parties. The primary provocation for the landowners was the movement’s demand for the abolition of hereditary land rights and greater “rights to the tiller.”

The landholders responded affirmatively by making a strategic departure to embrace the spirit of the peasant movements. Landholders now invoked caste pride and primordial associations with the land to foresee a role within these movements. The subtlety of the shift offered a delicate balance between navigating the last vestiges of empire and the anticipation of political possibilities in postcolonial India.

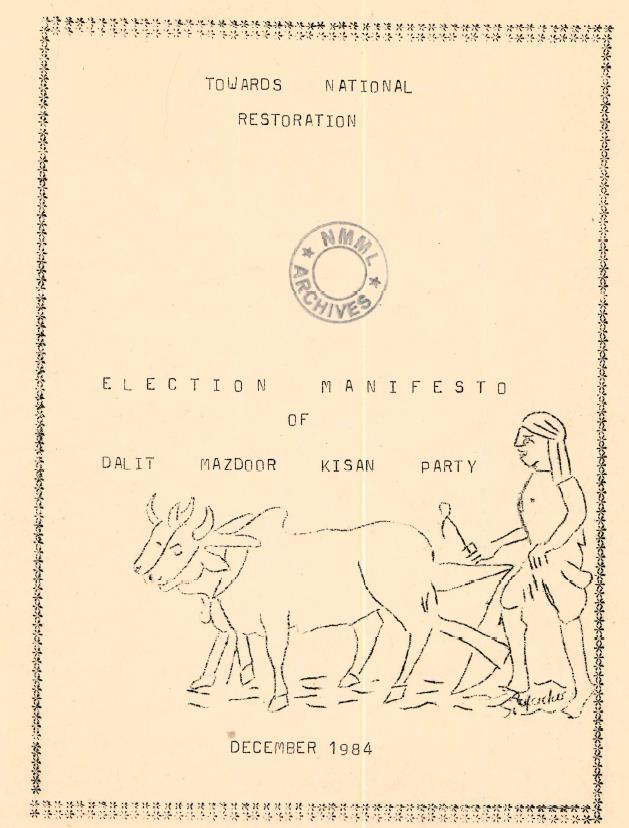

More than a decade after building a formidable base to represent rural backwardness, Singh broke away from the Congress. He formed his own party in 1967, named the Bharatiya Kranti Dal. But the twilight of Singh’s career in the 1980s offers a useful glimpse of the new possibilities that emerged in the north. Before his demise, Singh launched a new party titled the Dalit Kisan Mazdoor Party (DMKP).

Manifesto of the Dalit Mazdoor Kisan Party. (1984. Source: Charan Singh Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

The party’s 1984 election manifesto tries to highlight the plight of joblessness and poverty as it calls for an overall uplift of rural India. It repeats an earlier strategy adopted by Backward Class leaders who used the excuse of resisting backwardness to secure subsidies and concessions to help dominant landowning caste groups. The strategy had worked this far essentially because the surrender to the cause of peasanthood had yielded political and financial gains for the landowning castes. The undercurrents of communal disharmony that were as much a part of the agrarian politics would, however, have to wait until the demolition of the Babri Masjid in 1992.

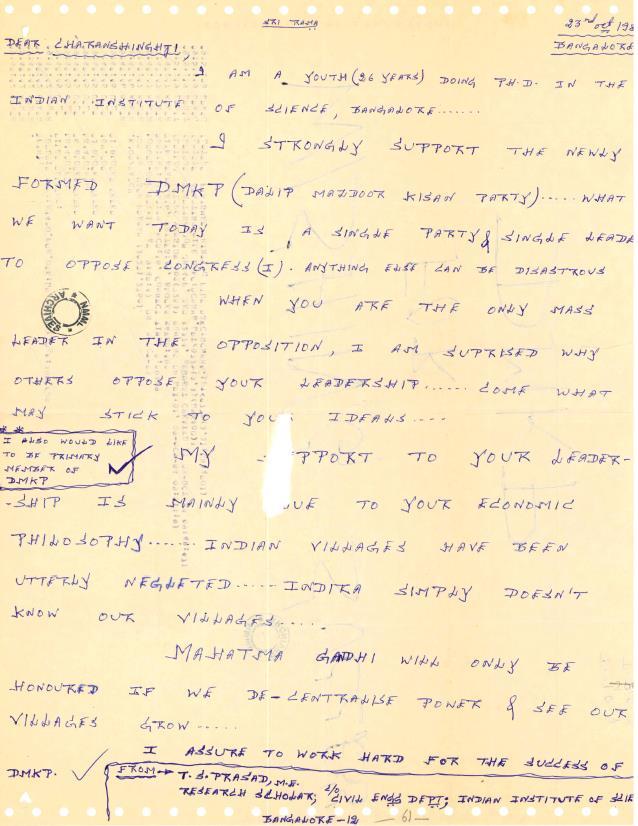

Letter of support to Charan Singh from a PhD student at the Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore. (Source: Charan Singh Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

The formation of the DMKP resulted in a wave of congratulatory messages that arrived from across India. One such letter, written on a sheet taken from a student’s notebook, arrived from a doctoral candidate at the Indian Institute of Science in erstwhile Bangalore. The student congratulates Singh for starting the party and wishes for him to emerge as an important force to fight the Congress. The DMKP did not find much electoral success also because the 1980s witnessed an assertive Congress and a resolute emergence of far-right politics under the umbrella of the Ram Mandir movement.

The demolition of the Babri Masjid on 6 December 1992 invited a new paradigm of agrarian politics. The old festering issues of communalism that stayed hidden behind the veil of Backward Class politics rose to the surface and reconfigured the responses of dominant caste alliances. Singh’s demise in 1987 meant that he would not bear witness to the future outcome of the movement that he had steered. His proteges and the larger demographic of dominant caste outfits would gradually find a resting place with far-right majoritarianism.

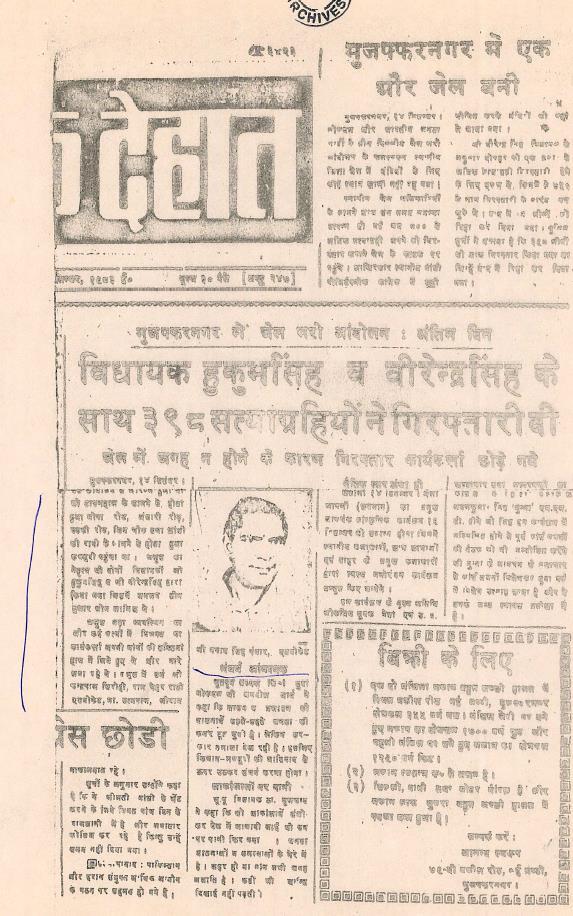

The Dehat reports on the arrest of activists Hukum Singh and Virender Choudhary while participating in the Jail bharo (fill the jails) protest in Muzaffarnagar. (1984. Source: Charan Singh Papers- Nehru Memorial Library, New Delhi.)

The newspaper cutout draws attention to peasant leaders like Hukum Singh and Vijender Choudhary, who were Gujjar caste leaders from present-day West UP. The two made their early inroads into politics along with Charan Singh and were actively involved with the DMKP in the 1980s. In the decades following the 1990s, they would emerge as leading voices of the far-right. The late Hukum Singh, a BJP parliamentarian from Kairana in West UP, was notorious for raking up the issue of the Hindu exodus in 2016. Peasant leaders like Naresh Tikait of the Bharatiya Kisan Union (BKU) publicly endorsed the vitiated Jat Mahapanchayat (caste gathering) in 2013 that resulted in the infamous Muzaffarnagar riots and displaced over 70,000 Muslim families.

The capitulation of peasant caste leaders to far-right politics has been a topic of debate for some time now. This has also been the case because the far-right articulations of peasant castes are often shrouded in the defence of custom, tradition or the struggle against rural backwardness. A survey of colonial and postcolonial print literature produced within agrarian spaces shows how the contemporary rise of far-right vigilante politics in the north can be understood through an examination of Backward Class politics. The longer history of such a politics underlines the strategic shift from, say, landowning to peasanthood and then to the far-right. The notes from the rural archive seem to suggest that the demolition of the Babri Masjid offered the opportune moment for the fruition of a fertile ground for majoritarian politics in the agrarian north.

To learn more about agrarian politics, read Vishal Singh Deo’s reflections on the patterns of majoritarianism in the agrarian north. To read more about visual and cultural politics resulting from the demolition of Babri Masjid, read Prabhakar Duwarah’s article on Prashant Panjiar’s photographs, Arushi Vats on the Sahmat Collective and Najrin Islam on Ritesh Sharma’s Jhini Bini Chadariya.